For much of this year, activists across Los Angeles staged protests and flooded city meetings with angry phone calls, demanding that Mayor Eric Garcetti and the City Council zero out funding for the Police Department.

“We want the dismantling of the LAPD entirely,” filmmaker Carter Moon, 27, said during one budget hearing. “We are working toward abolition, and every day you are just getting in our way.”

Council members ultimately cut the department’s budget by $150 million, slashing overtime pay and taking police staffing to its lowest level since 2008.

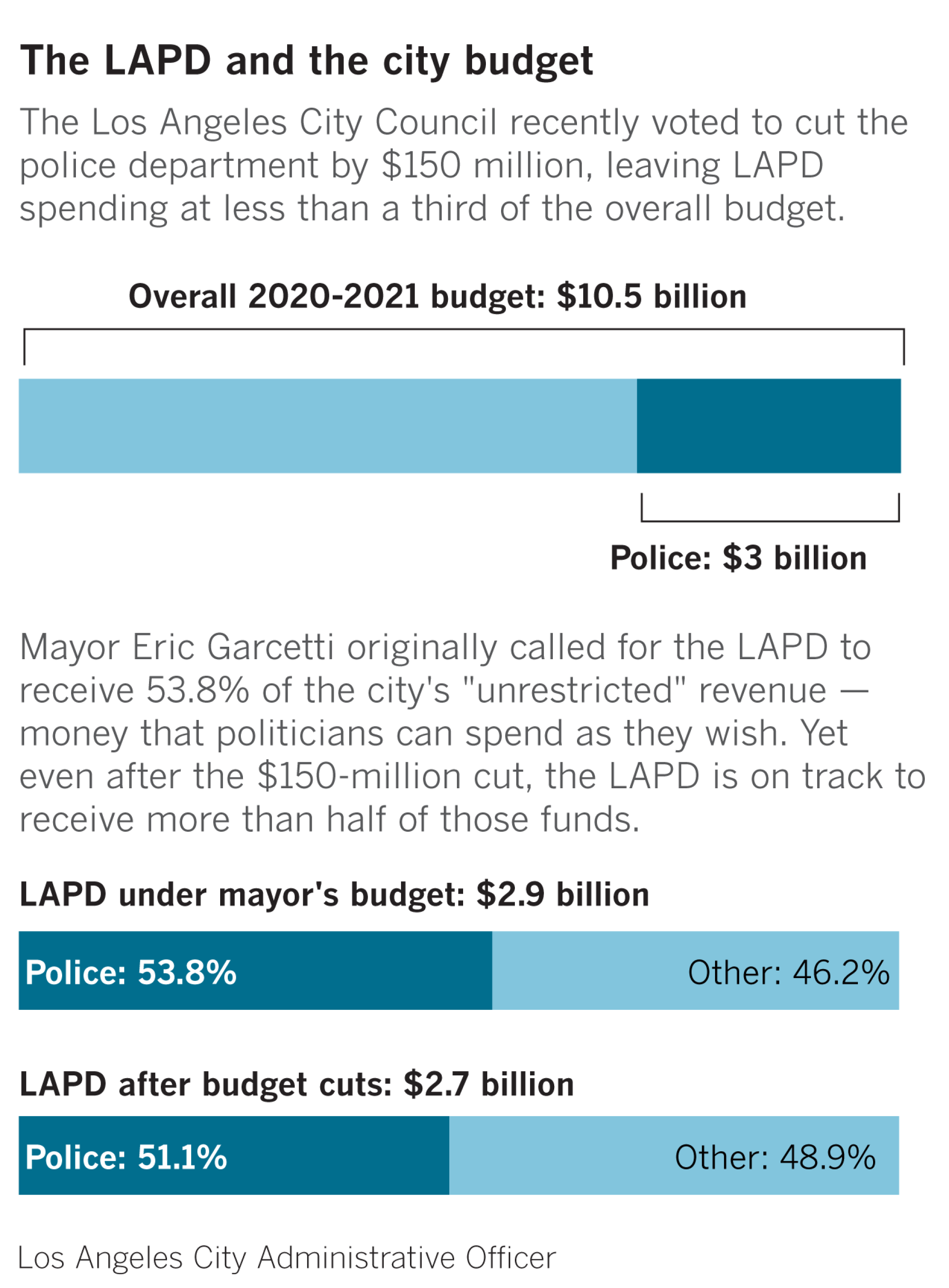

Yet even with those reductions, LAPD spending will remain at roughly $3 billion, about the same as last year. The department is still on track to consume 51% of the city’s “unrestricted” revenue — taxes and other city funds the mayor and council can spend any way they want, according to budget analysts.

If city leaders continued cutting police spending by the same amount every year, Black Lives Matter-Los Angeles and their allies would not reach their target for defunding the LAPD until 2040, according to a Times data analysis. And because nearly one-fourth of police spending goes toward officers’ pensions — a financial obligation of the city — such a goal may be legally impossible anyway.

Those data points serve as a backdrop for a series of virtual town hall meetings on “re-imagining” public safety at City Hall, which will begin this week. As they respond to the demands for change that followed the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, council President Nury Martinez and her colleagues have begun asking residents in surveys to define the phrase “defund the police.”

Martinez and her colleagues voted last month to reduce the LAPD’s operating budget by 8%. But they did so only after Garcetti’s spending plan, which increased the department budget by 7%, went into effect.

Activists say they’re encouraged to see the council exploring proposals for moving some duties, such as traffic enforcement, out of the LAPD and into other city agencies. And they vowed to keep pressing City Hall to make deep cuts to the Police Department and use the money for other needs.

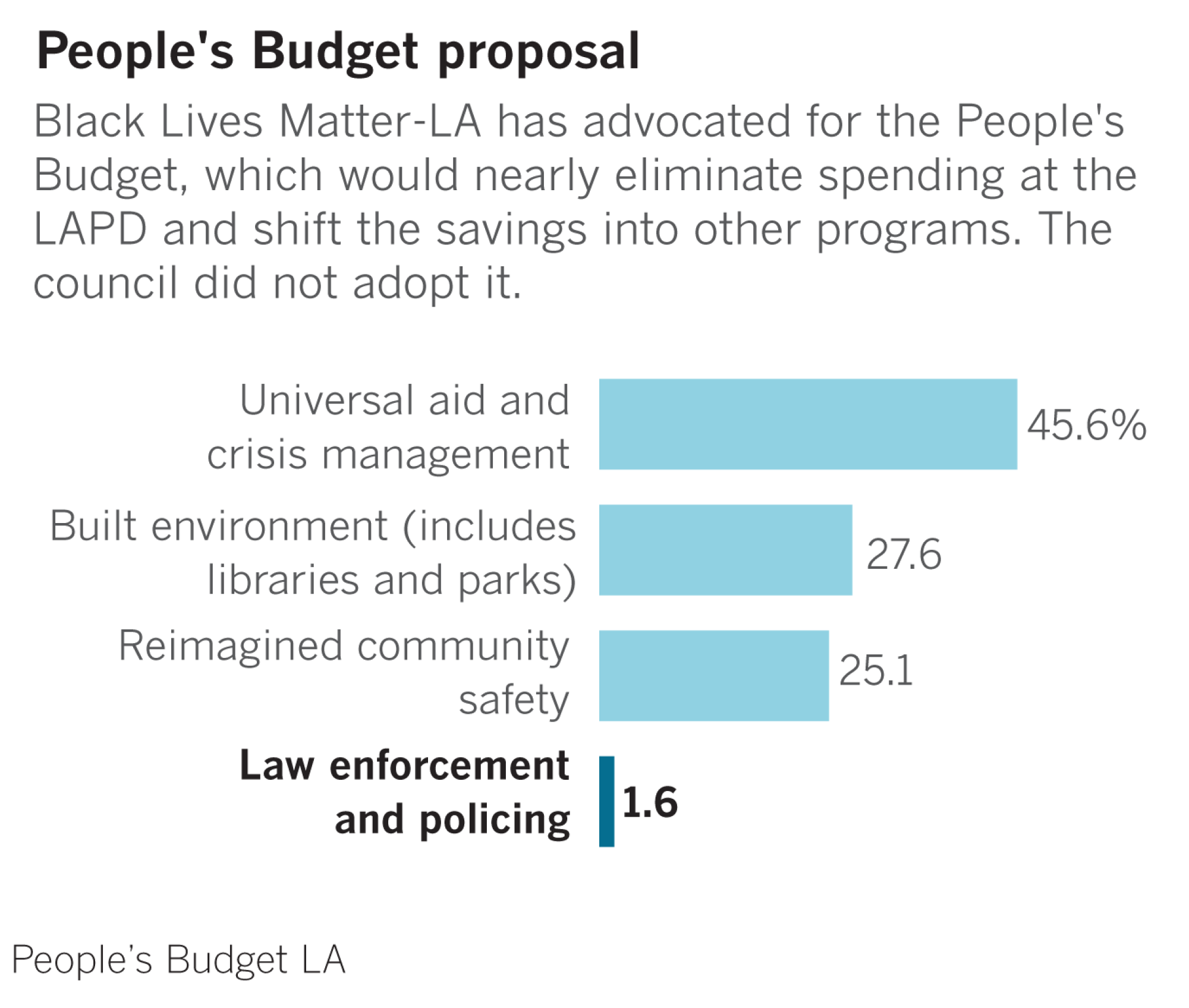

“We’ve gotten to a place where divestment [in the LAPD] is officially on the table,” said David Turner, a researcher for Black Lives Matter-L.A., who helped collect the data for the People’s Budget, an alternative plan for city spending that would nearly eliminate LAPD funding.

Turner called the $150-million cut a “step in the right direction.” But Pete White, a longtime LAPD critic who heads the anti-poverty group Los Angeles Community Action Network, said he viewed the move as a distraction aimed at getting protesters off the streets.

“The $150 million is nothing more than a political overture and a fig leaf,” he said. “Do we want it? Yes. Is it enough? No.”

***

In this year’s debate over racism, police brutality and public-safety spending at City Hall, progressive activists seized on a key statistic: Garcetti’s budget for 2020-21 devoted nearly 54% of the city’s unrestricted revenue — money that can go toward any program — to the LAPD.

Grassroots organizers said the figure showed that city leaders had their priorities wrong. They called for the money to be redirected to housing, healthcare and other services aimed at safeguarding residents’ economic and emotional well-being.

The union that represents LAPD officers said such a move would spell disaster for the city, leading to more unsolved crimes and a major spike in violence. They also criticized protesters for focusing on unrestricted revenue, noting that those funds represent only half of overall city spending.

Once every city program is accounted for, the LAPD makes up less than a third of the city’s $10.5-billion budget, said Dustin DeRollo, spokesman for the Los Angeles Police Protective League.

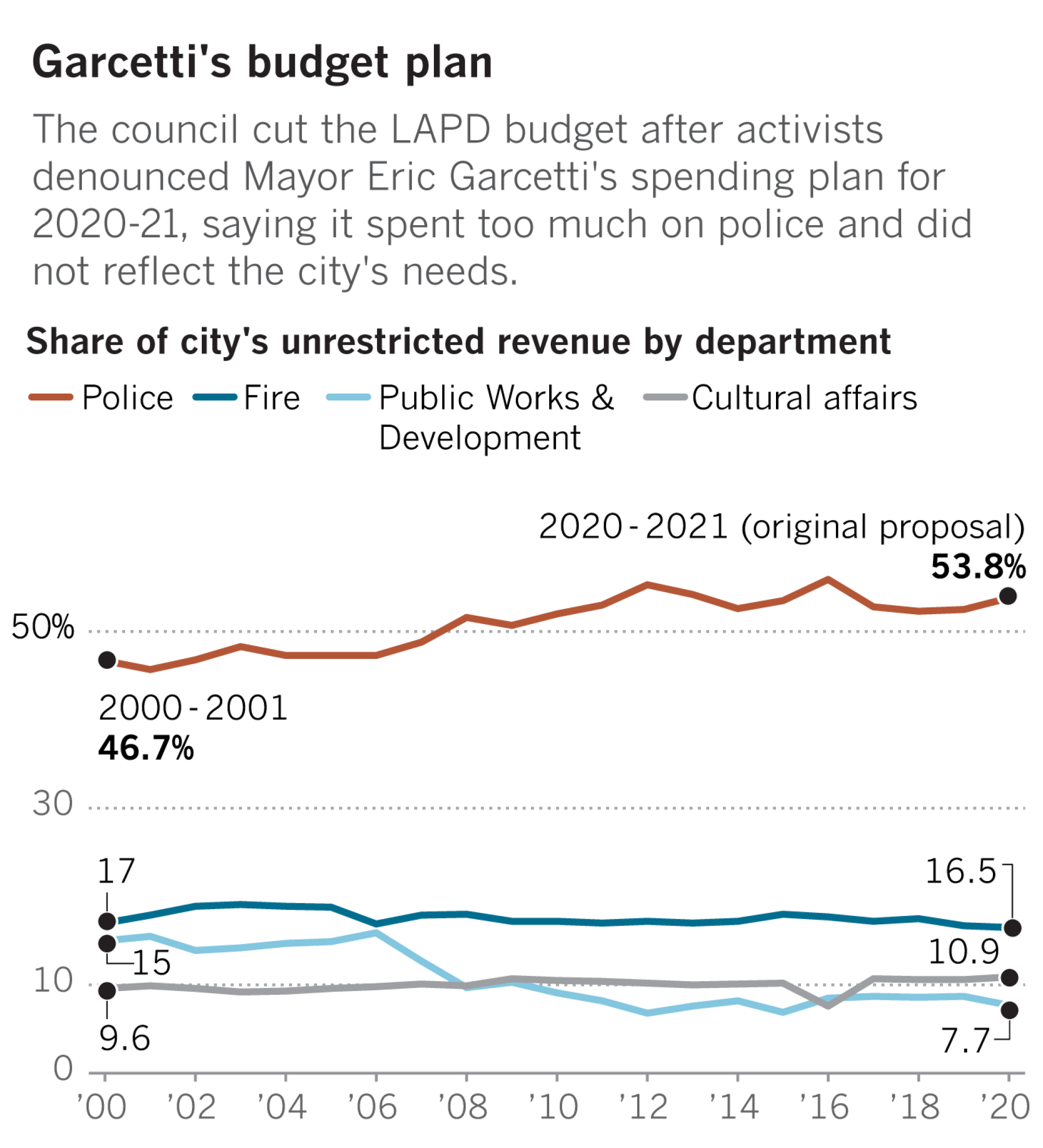

To get a better understanding of the growth in police spending, The Times examined L.A. city budgets spanning 20 years and found that the LAPD’s share of unrestricted revenue did increase over that period, moving from more than 46% to nearly 54%.

The vast majority of that increase took place between 2005 and 2013, when Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa and Garcetti, then the council’s president, embarked on an expensive mission to expand the LAPD’s ranks.

When Villaraigosa took office in 2005, crime was a front-burner issue. L.A. experienced 489 homicides that year, almost twice the number recorded in 2019.

On the campaign trail, Villaraigosa had hammered his opponent, then-Mayor James Hahn, for promising to hire 1,000 officers and falling far short. Villaraigosa vowed to succeed where Hahn had not.

Former City Councilwoman Jan Perry, who represented part of South Los Angeles, supported the LAPD hiring plan at the time. During that period, she said, her district had been hit hard by gun violence. Her office raised money to help pay for funerals and heard regularly from residents demanding a faster police response.

“I got really angry about helping people after they’d been harmed and not helping them enough before they’d been harmed,” she said.

Some of the loudest critics of the LAPD hiring initiative were not civil rights leaders but homeowner groups in more heavily white sections of the Westside and San Fernando Valley, who objected to the mayor’s plan to pay for the added personnel: hiking trash pickup fees.

When Villaraigosa took office, the city’s Bureau of Sanitation was spending $187 million per year to keep the trash bills of homeowners and small apartment buildings artificially low. As a result, the sanitation agency was consuming 6% of the city’s unrestricted funds. The LAPD consumed 47%.

Villaraigosa and the council tripled the trash fees, freeing up money for the city budget, and hired more than 800 additional officers. By the time he left office, the sanitation subsidies were gone, and the LAPD — employing 10,000 officers — was consuming about 54% of the city’s unrestricted revenue.

But maintaining the larger police force came with trade-offs. After the 2008 recession plunged the city into financial crisis, L.A.’s elected leaders reduced tree trimming, sidewalk repairs, library hours and firefighter staffing, even as the LAPD kept hiring. They did so even though violent crime had plummeted more than 70% from its peak in 1993.

“There was a collective fear that, without maintaining a commitment to a particular size of the [LAPD], the crime that the city experienced in the ’90s and early 2000s would surface again,” said Miguel Santana, the city’s top budget official at the time.

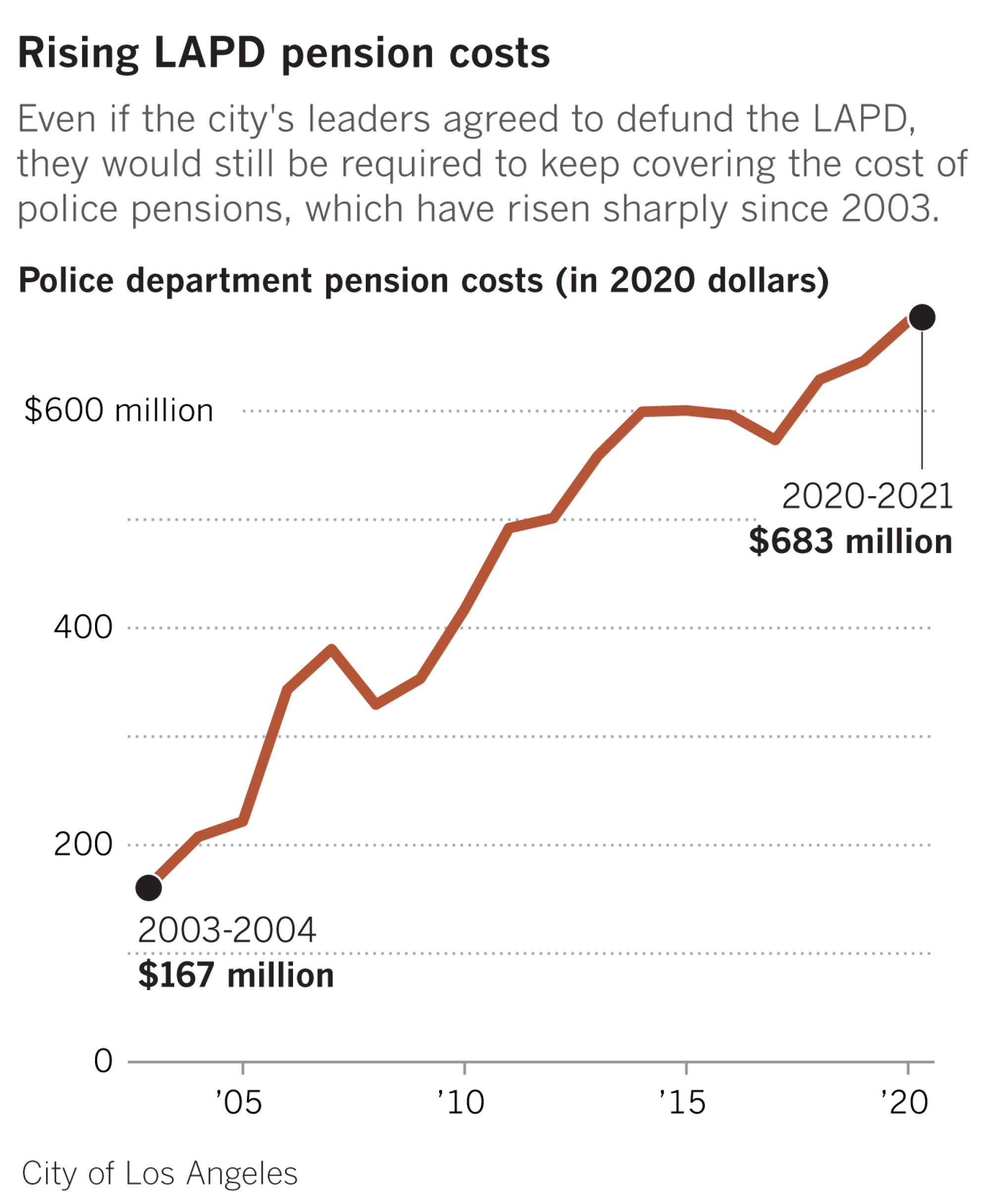

Many of the city’s programs were eventually restored. But the economic downturn delivered huge losses to the city’s public-safety pension fund, leaving taxpayers to make up the difference. The share of the city budget devoted to LAPD pensions tripled during Villaraigosa’s tenure.

Garcetti has defended the LAPD hiring initiative in recent weeks, saying it was accompanied by an expansion of late-night youth programs and other community safety initiatives. Those investments, taken together, saved thousands of lives, he said.

“Some of us remember when we had open warfare on some of our streets,” he said.

Akili, an organizer with Black Lives Matter-Los Angeles who goes by a single name, took the opposite view, calling the police hiring initiative a big mistake. The LAPD expansion began when the department was pursuing a “broken windows” approach to public safety, aggressively enforcing misdemeanors, he said.

“It resulted in over-policing,” said Akili, who volunteered for Villaraigosa’s 2005 campaign. “And when you over-police us, you wind up arresting a lot more of us. And you end up killing a lot more of us.”

Villaraigosa declined to comment. When he was mayor, he repeatedly attributed the city’s huge drop in crime to his administration’s handling of public safety. “Growing our Police Department and ... community policing is a big reason why we are safer today,” he told The Times in 2013.

Still, some criminal justice experts caution against drawing a link between crime rates and the size of a particular law enforcement agency, saying the body of studies do not show a clear correlation.

New York City’s Police Department shrank by thousands of officers during the Great Recession yet still experienced major reductions in crime, said James McCabe, professor of criminal justice at Sacred Heart University and a retired New York police officer.

“Why does crime occur? There are a lot of reasons. The police are a part of it. The economy is part of it. The demographics are part of it,” McCabe said. “More cops equals less crime — it’s not that simple.”

What’s more important, McCabe said, is how officers are deployed. Cities should be analyzing criminal data and other factors to determine how many officers they need, he said.

***

By 2013, L.A. residents had lost their appetite for increasing the size of the LAPD. City Controller Wendy Greuel ran for mayor that year on a plan to hire 2,000 additional officers, taking the force to 12,000. Garcetti denounced the idea as unrealistic and won the election.

That same year, L.A. voters rejected a sales-tax hike billed as a way of shielding the LAPD from budget cuts. Low-income neighborhoods in South Los Angeles voted strongly in favor of the measure, while voters in the wealthier areas of the Westside and northwest Valley rejected it overwhelmingly.

Nevertheless, Garcetti kept sworn staffing above 10,000 and even expanded the LAPD’s operations, securing a contract to patrol L.A.’s buses and trains. While Villaraigosa worked to keep a lid on police salaries, Garcetti as mayor backed an expensive package of raises and bonuses, boosting the police budget even more.

Tyran Steward, a civil rights professor at Williams College, called those increases “gross and reprehensible,” particularly in light of how much crime had fallen over 30 years. “You still have a commitment to a bloated police budget, again against the backdrop of a decline in crime,” he said.

LAPD retirement costs have continued growing and are on track to consume $683 million of the budget this year. Even if city leaders embrace the call to zero out police spending, they would be required to fund officers’ pension benefits.

Turner, the Black Lives Matter researcher, said he would be interested in exploring whether the city can cut the pensions of police officers who engage in misconduct that results in lawsuits against the city. After all, his group has already broken through a major political barrier: persuading City Council members that police staffing is no longer untouchable.

Because of this year’s cuts, the LAPD is on track to have 9,757 officers by mid-2021. With the council’s latest cuts, the department’s operating budget is expected to decrease by 1.5% compared to the prior year.

Times Staff Writer Dakota Smith contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.