‘Pension spiking’ is not protected by California law, top court rules

SAN FRANCISCO — For two decades, it was a treasured perk for some county employees across California: the ability to boost their pensions by cashing out unused vacation or sick leave, or working extra hours, at the end of their careers.

In some cases, workers received more in pension payments than they earned while working.

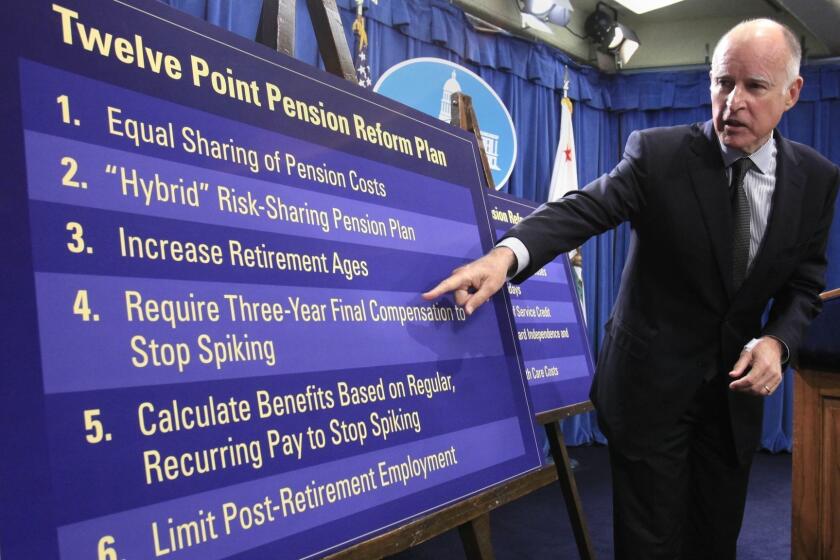

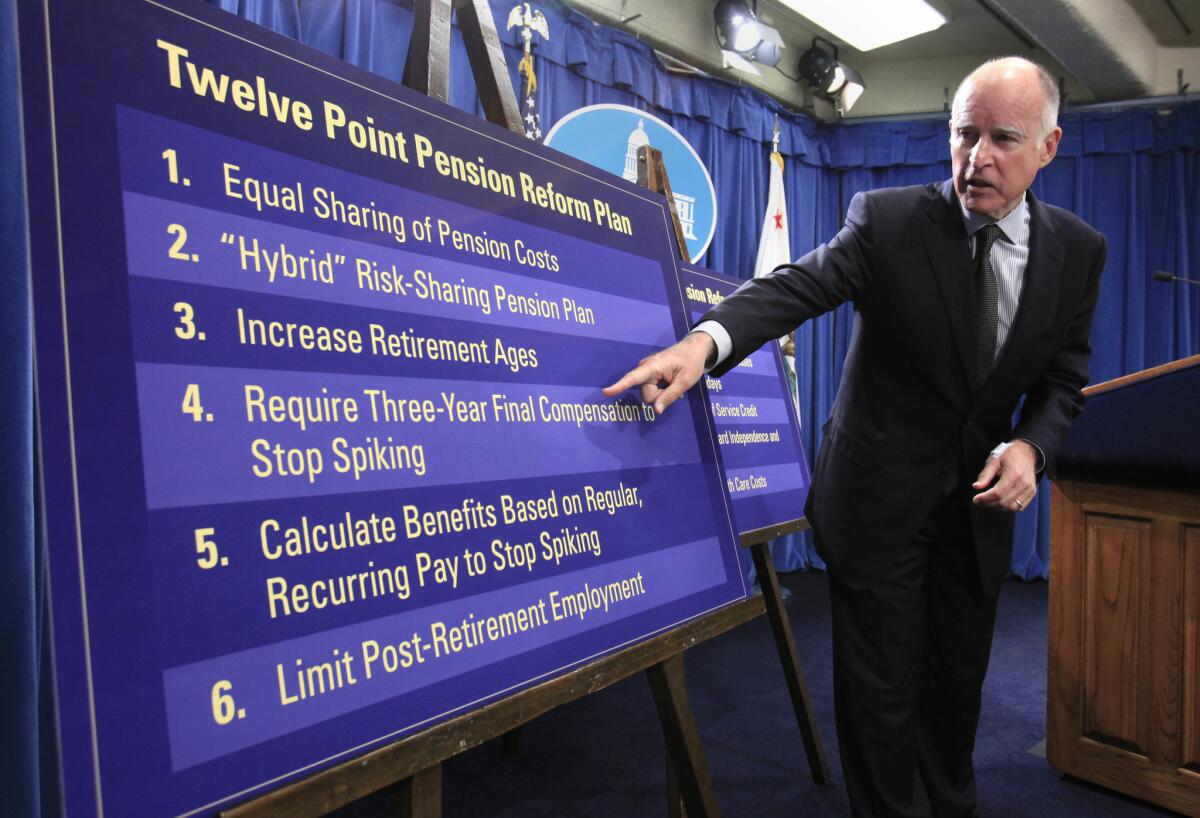

But with the state’s economy struggling and a pension crisis looming, then-Gov. Jerry Brown backed a sweeping reform measure in 2013 that prohibited county workers from “pension spiking.” Labor unions sued to overturn the new law.

On Thursday, in one of several closely watched pension cases, the California Supreme Court sided with the state, unanimously upholding a provision of the 2013 law that prohibited pension spiking by county workers.

In a decision written by Chief Justice Tani G. Cantil-Sakauye, the court said the law that ended pension spiking for county employees was enacted “for the constitutionally permissible purpose of closing loopholes and preventing abuse of the pension system.”

It was the second time in less than two years that the justices weighed in on a pension issue without touching a broader question of extreme significance to workers as well as governments — the fate of the so-called California Rule, a 65-year-old legal doctrine that strongly protects public pensions for all government workers except new hires.

David E. Mastagni, who represented Alameda County employees in the case, said he was disappointed for them but glad the California Rule survived.

Thursday’s decision could be perceived as a “chipping away” of the rule, he said, but it indicated the court would limit rollbacks of pension benefits to narrow “modifications just to address perceived abuses or loopholes.”

Public pensions are calculated based on a worker’s highest year of earnings, and some public pension plans allowed spiking.

The California Supreme Court made it clear Monday that state and local governments may reduce pension costs by repealing certain benefits without running afoul of constitutional protections for public pensions.

Unions and public employee groups contended that the anti-spiking provision conflicted with decades of court decisions upholding the California Rule. It made California’s public pension protections among the strongest in the country.

The rule guarantees workers the pension they would be due under the benefit package in place on the day they were hired. Pensions are considered constitutionally protected contracts.

The formula for calculating retirement income could be changed only in a way that was neutral or advantageous to the worker, according to the rule.

Some business groups and others had urged the court to use the legal challenges to Brown’s pension package as a vehicle for weakening the California Rule, which would have affected public employees across the state. The court refused, writing instead a narrow decision.

“We have no jurisprudential reason to undertake a fundamental reexamination of the rule,” the court said.

In the ruling, the court said that lawmakers “must have the authority, discretion, and flexibility” to address such issues as pension spiking.

Requiring the government to offer a benefit to offset the elimination of pension padding would “significantly undermine” the Legislature’s efforts to close loopholes, the court said.

The decision upheld a state law barring the practice of pension spiking.

The decision on spiking applies to 20 counties that administer their pension plans under the County Employees Retirement Law of 1937, which the 2013 law amended. L.A., Orange, San Bernardino and San Diego counties are among them. The city of Los Angeles has a separate pension system.

Most state employees can still use accumulated sick leave to buy additional service credit, said Michael Jarvis, managing labor relations consultant for the law firm of Mastagni Holstedt. The 2013 pension law did not change that. At California State University, Jarvis said, it takes 250 days of sick leave to get one additional year of service credit, raising the employee’s pension from 1.5% to 3% a year.

Timothy K. Talbot, who represented the employees of Contra Costa and Merced counties in Thursday’s case, said the ruling would be “very disappointing and devastating” to his clients because “they were relying on that benefit,” which he called “vacation cash-out.”

The benefit was part of court-approved settlements dating to the late 1990s and was used by the counties to lure people to work for them, he said.

Ted Toppin, chairman of Californians for Retirement Security, a 1.6-million-member coalition of public employees and retirees, expressed relief that the decision “unequivocally” upheld the California Rule and protected “the retirement security of California public servants … working on the front lines to protect Californians during the pandemic.”

But he said the ruling did “seem to undermine the retirement security of Alameda County sheriff deputies,” one of the groups of employees who filed suit.

“Their employer and retirement system made a promise to them that the court decision now allows them to break,” Toppin said. “That is unfair and unfortunate. If public employers make a pension commitment to their workers, they should keep it.”

Gov. Gavin Newsom, whose office argued in favor of the 2013 law, did not comment on the ruling.

In another unanimous pension decision last year, the state high court said the government could reduce pension benefits without running afoul of the California Rule.

The court in that case upheld California’s 2012 repeal of an “air time” benefit that allowed state workers to buy credits toward retirement service.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.