California Supreme Court curbs a pension benefit but preserves ‘California Rule’

Reporting from San Francisco — The California Supreme Court made it clear Monday that state and local governments may reduce pension costs by repealing certain benefits without running afoul of constitutional protections for public pensions.

In a unanimous decision written by Chief Justice Tani-Cantil Sakauye, the court upheld California’s 2012 repeal of an “air time” benefit that allowed state workers to buy credits toward retirement service.

The decision was the court’s first in a series of pending pension disputes it has agreed to review.

Some legal analysts said the ruling suggested the court would strive to rule narrowly in future pension cases. Others contended the justices eventually would have to address how far state and local governments may go in reducing pension liabilities.

Public employers want the court to make it easier to cut pensions for current employees to tackle hundreds of billions of dollars in pension shortfalls.

Labor unions are fighting cutbacks, pointing to decades of court precedent that says California’s public pensions are contracts protected by the state Constitution.

In ruling for the state Monday, the high court distinguished core pension benefits from the retirement credits at issue.

Pensions are a form of deferred compensation protected by contract law, but the opportunity to buy retirement credits was simply an optional benefit, the court said.

It likened the option to the opportunity to choose from various healthcare plans, to purchase disability insurance coverage or create a flexible spending account to pay for health and child care costs with pre-tax dollars.

“Unlike core pension rights,” the court said, the opportunity to purchase retirement credits was “not granted to public employees as deferred compensation for their work.”

A term or condition of public employment is not constitutionally protected “solely because it affects in some manner the amount of a pensioner’s benefit,” the court said.

Although the court ruled for the state on the benefit, it refused requests by the state and pension reformers to dilute the decades-old legal protections for public employees.

For more than 60 years, California has adhered to a legal rule that guarantees workers the pensions that were in place the day they were hired.

Known as the “California Rule,” the protective legal doctrine has stymied state and local lawmakers wrestling with hundreds of billions of dollars in pension shortfalls.

The court declined to address the controversy over the rule, saying it was unnecessary to resolve the dispute.

Gregg McLean Adam, who represented the unions, said he was disappointed.

“Certainly because we lost, there will be those who suggest this is the writing on the wall” for future pension rulings, he said.

But Adam said he didn’t see anything in Monday’s decision “suggesting the court was backing off” the California Rule.

“Everyone is just going to have to wait for the sequel,” he said.

University of Minnesota law professor Amy B. Monahan, who specializes in employee benefits law, said it was “incredibly difficult” to predict from Monday’s decision how the court would decide the other pension disputes.

“There are a lot of good reasons for the judges to stick with existing precedent, but the appellate courts have given them a different path if they want to take it,” she said.

Emory University law professor Alexander Volokh said Monday’s decision gave the court “a road map to carve out certain things from the scope of the California Rule.”

“But I don’t see them doing any sort of wholesale rollback,” Volokh said.

Daniel M. Kolkey, who represented a free-market think tank in the case, said the ruling suggested the court would be flexible in allowing state and local governments to repeal some benefits.

But he also predicted that the court eventually would have to decide whether the California Rule should be limited.

Ted Toppin, chairman of Californians for Retirement Security, expressed gratitude that the court left the rule intact.

“Thankfully, the decision protects the retirement security of California’s nurses, teachers, firefighters, school employees and countless other public servants and retirees dependent on their hard-earned pensions,” Toppin said.

Still, the court could redefine the rule in a later case.

Timothy T. Coates, who represented the Los Angeles County Employees Retirement Assn. as a friend of the court, said no conclusions could be drawn about the court’s leanings on the protective precedent.

“I don’t take anything from this case as tipping their hand on the California Rule,” he said.

The air time benefit, created by the Legislature in 2003, permitted employees to pay a fee to add an extra five years to their work history for pension purposes.

Known as air time because the employee does not actually work, the benefit was offered to workers with at least five years of state service.

An employee of 20 years could qualify for a pension based on 25 years of contributions, which was particularly attractive to workers who took a break from their government jobs to take care of family or work on political campaigns.

As part of pension reform law, the state repealed the air-time benefit in 2012. Unions sued, arguing the repeal violated the California Rule.

Under current law, pensions are treated as contracts protected by the California Constitution. Monday’s decision did not alter that, but made it clear that a benefit that simply affects a pension may not be untouchable.

The formula for calculating retirement income generally can be changed only if it is neutral or advantageous to the employee, courts have ruled in the past. It cannot be reduced, except for new hires.

By deciding the air-time benefit did not amount to a pension promise, the court allowed public employers to shave retirement costs without toppling a bedrock legal principle protective of workers.

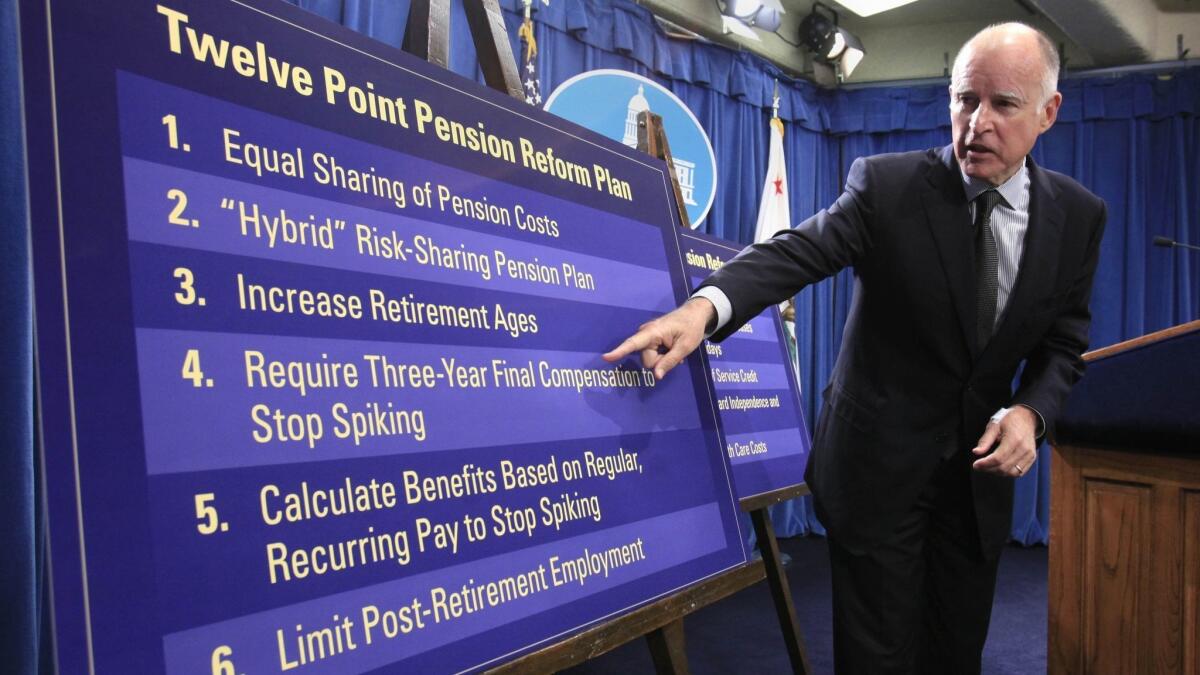

A similar case before the court involves “pension spiking.” A three-judge Court of Appeal panel decided in 2016 that Marin County had the right to bar workers from spiking their pensions.

Pension spiking occurs when an employee’s pay is inflated during the period on which retirement is based — usually at the end of a worker’s career.

This can be done by cashing in years of accumulated vacation or sick pay or volunteering for extra duties just before retirement.

In some cases, spiking has created pensions higher than the workers’ salaries.

The Court of Appeal in that case ruled that public retirement plans were not “immutable,” and could be reduced. The law merely requires government to provide a “reasonable” pension, the intermediate court said.

That decision was a major departure from the California Rule.

By distinguishing the air time and pension-spiking cases from pension precedents, the court could pursue a middle ground, allowing government to reduce some pension costs but still leaving protections for workers in place.

Twitter: @mauradolan

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.