They lost loved ones to police violence. George Floyd’s killing has made the pain new again

For families who have lost a loved one to police violence, there are two truths most agree on: The pain never goes away, and every new fatal encounter with law enforcement makes it raw again.

As the nation and world mourn the death of George Floyd, these five Californians continue to grieve over law enforcement killings closer to home. Their tragedies are made worse, they say, by the systemic racism that remains in the American criminal justice system and continued use of fatal force that seldom results in repercussions for the officers involved.

For some, speaking out is a balm and a necessary part of an ongoing fight. For others, it is trauma endured so that the person gone is not forgotten.

Here, they share their stories:

Brigett McIntyre, mother of Mikel McIntyre

Back when she was young, long before two police officers shot her son in the back, Brigett McIntyre dreamed of having a baby.

Doctors had told her she couldn’t carry a pregnancy, so when she gave birth to her only child, Mikel, after many miscarriages, it was as much a triumph as a joy.

“I asked God to give me a son and he did,” McIntyre said. “He was beautiful to me. He was a delight.”

When she saw the video of George Floyd recently, “that hurt me to my heart,” she said. She imagines Mikel calling for her as he bled out on the gravel edge of a highway, a torment so piercing she can’t take part in protests.

Some mornings, the depression and anxiety, the fear of police and the loneliness, overwhelm her.

“There is not a day that goes by that I don’t cry for my son,” she said. “I can’t go out. I can’t speak…. I just want to lay in bed all day, close the shades and just sit and do nothing.”

In 2017, Mikel McIntyre, then 32, started acting strangely, unable to sleep. A talented baseball player — he’d been honored by the National Assn. of Intercollegiate Athletics while playing in college and was an outfielder on a minor league team — he’d never had any health problems, but now his mother was worried. She convinced him to travel with her from the Bay Area to a suburb of Sacramento to visit her grandmother, hoping the change would do him good.

McIntyre’s mental state worsened, though, and his mother called police for help. Responding authorities declined to take McIntyre for mental health care.

Later that day, McIntyre and his mother argued over the car keys in the parking lot of a shopping mall, and a bystander called police.

Investigators said that McIntyre hit an officer in the head with a large rock and ran under a nearby freeway overpass, sparking a massive police response. In the next minutes, official accounts say, McIntyre threw another rock that hit a police canine, then ran down the berm of the roadway.

An officer parked on the far side of the freeway, left his car and began shooting, loading a second magazine in his Glock as he advanced across the lanes. It was the same officer who had responded to one of the calls for mental health care, and who later said he recognized McIntyre from that earlier encounter. A second officer, the canine handler, also fired shots, according to official investigations.

McIntyre was struck multiple times, mostly from the rear, and was pronounced dead that night.

“He did nothing but run for his life, and he shouldn’t have had to run,” his mother said.

These videos are from the scene of the fatal police shooting of Mikel McIntyre. Sacramento County Sheriff Scott Jones refused to release the footage until last month, after a legal challenge by The Times and the Sacramento Bee.

In an unprecedented occurrence, Sacramento County’s inspector general questioned whether McIntyre posed a deadly threat when shot. Sacramento County Sheriff Scott Jones demanded the inspector general be fired, and the Board of Supervisors complied.

The county district attorney, Anne Marie Schubert, found the shooting justified. More than a year after McIntyre’s death, Jones said that his deputies “acted within policy. They acted within law and they came to a successful though unfortunate resolution.”

A civil case was settled recently for $1.75 million.

It bothers Brigett McIntyre that few people know the circumstances of her son’s death, in part because Jones refused to release the video until last month after a legal challenge by The Times and the Sacramento Bee. She would like to see Jones out of office.

“Why are we paying their salary to kill us? Where is the justice?” she asks. “Every mother who has lost their child to police violence, my heart goes out to them because I understand their pain. They have taken away something that was precious to us. He was my baby. He was my blessing. And they took that for no reason.”

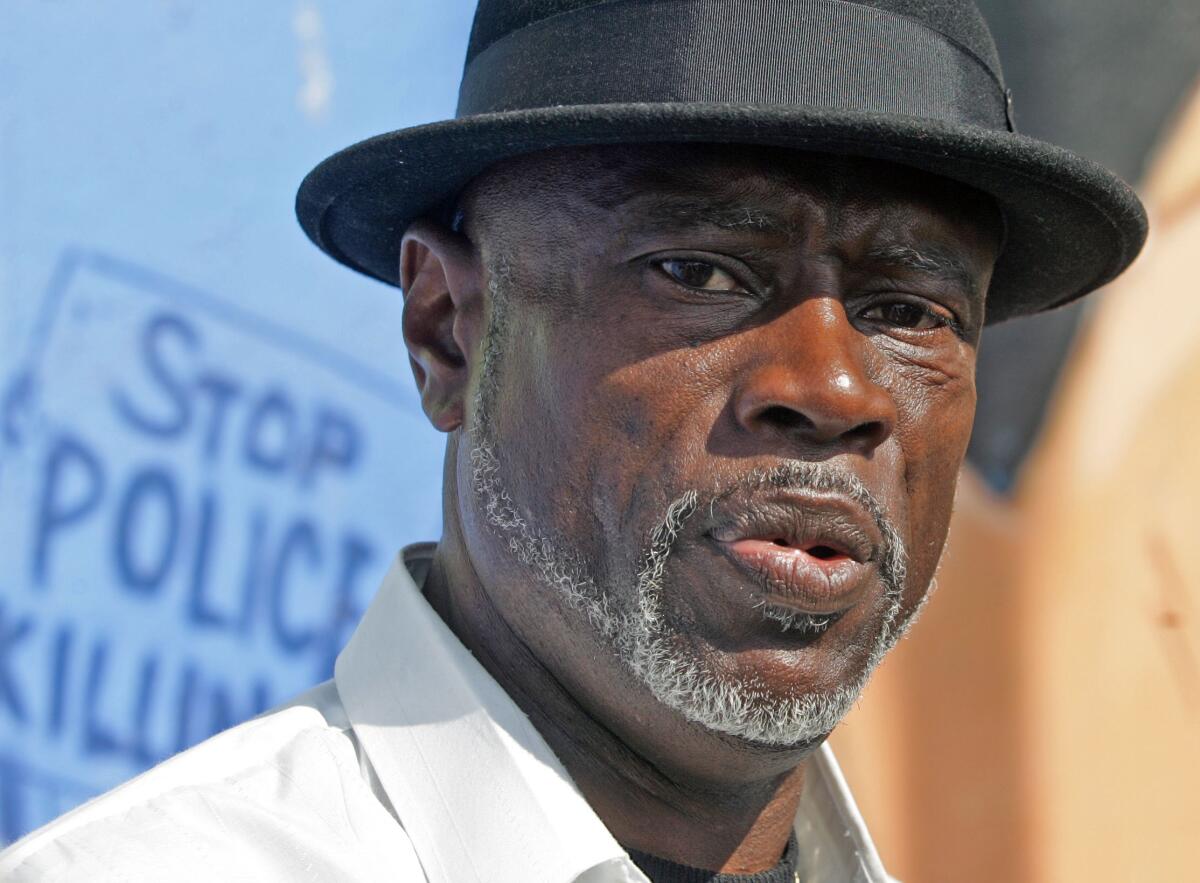

Cephus Johnson, uncle of Oscar Grant III

If there is an elder statesman of police reform in California, it is Cephus “Uncle Bobby” Johnson.

His nephew, Oscar Grant III, was shot in the back by a transit police officer in the Bay Area in 2009. Caught on video, it sparked uprisings and was eventually memorialized in the film “Fruitvale Station.”

The video of Floyd “created much, much pain,” Johnson said, bringing home “how sadly things haven’t changed.”

After Grant was shot, Johnson said, he spent the first year angry and had a “rude awakening” that he had been blind to the full scope of racism in the United States, in part because he was educated and economically secure.

“I was in many arguments in those early days, adjusting my political ideology on how to get justice,” Johnson said. “That’s what changed me, recognizing that I can’t think it’s all about me and my own personal success in this world.”

He attended every day of the trial of Johannes Mehserle, the officer who shot Grant. Mehserle was convicted of involuntary manslaughter, claiming he mistook his gun for his Taser, and was released from prison in 2011 after serving 11 months of a two-year sentence.

Ultimately, Johnson decided that for him, the path to change was through legislation. He has been a fixture at the state Capitol and an instrumental force in passing almost every piece of police reform legislation in the last decade, including last year’s changing of the standard for when police can use deadly force to when it is “necessary,” not just “reasonable.”

That standard is now being discussed at the national level, and Johnson hopes to soon testify before Congress about it. He would also like to see a national database of misconduct records of every law enforcement officer, to prevent those with poor histories from moving from agency to agency.

But Johnson has also come to believe that law alone isn’t enough. Along with reforming policing, Johnson spends his time talking to youth of color.

“They are the ones that grew up and sadly watched their mamas cry, heard [my] voice, ask themselves the question, ‘Does my life really matter?’” he said.

He said he understands the anger of current uprisings. Black Americans “have been deprived for so long from just having a piece of the so-called pie here in the United States that they are willing to go through a broken window just to have a piece of something,” he said. “How did we get to that point?”

Tommy Twyman, mother of Ryan Twyman

While thousands spilled into the streets of Los Angeles and cities around the world in recent days, Tommy Twyman mostly kept close to home.

It was her son’s birthday. Also, the first anniversary of his fatal shooting by Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies.

“It was a heavy week for me,” Twyman said. “I feel so drained, I just want to close my eyes and sleep.”

Her son, Ryan Twyman, 24, was shot at more than 30 times by two deputies last June at an apartment complex in Willowbrook. Twyman was unarmed in his car; an open rear door hit one of the deputies while he was slowly reversing.

The Sheriff’s Department said Twyman was previously convicted of carrying a loaded gun and being a felon in possession of a firearm. He was on probation at the time, and deputies had been trying to arrest him for several weeks. Twyman’s parents say they believe the shooting constituted excessive force and have filed a civil suit.

“There were a million different ways they could have taken him out of that car,” his mother said.

Ryan Twyman left behind three sons, ages 3, 2 and 1. The oldest, his father Charles said, reminds them of Ryan.

“His little walk is the same,” Charles Twyman said. “It brings tears to my eyes.”

Tommy Twyman said her son struggled to keep jobs because he had seizures. He spent much of his time with his dogs, breeding pit bulls.

“Every photo is of him holding a dog,” she said. “He was happy to be with them.”

Officials didn’t respond to requests seeking comment about the case.

“These protests have been bittersweet,” Tommy Twyman said. “I see people carrying my son’s picture, saying his name, but it also reminds me that justice hasn’t been served and this has happened to so many others.”

Gabe Murphy, son of Christopher Murphy

Gabe Murphy’s life disintegrated when his father, Christopher Murphy, died after California Highway Patrol officers hogtied, handcuffed and shocked him with a Taser in 2016.

Once a linebacker with scholarship potential and “a very good kid to be around,” according to former coach Jelani Walker, the 17-year-old Gabe is now unsure if he will ever have a high school diploma. As a sophomore, he was invited to a practice day at both USC and UCLA, he says, but “I don’t get the emails from the colleges no more.”

Gabe’s trajectory since officers encountered his dad after a wrong-way car crash is a tale of generational trauma. He was a freshman then, just past his first season of high school football. The next summer, he couldn’t bring himself to put his pads back on. Football had been the glue between Gabe and Christopher.

“Whenever I was on the field, he was always there,” Gabe said.

Walker, his coach then, said Gabe had been one of the “vocal leaders of the team” and a “beast” in games. Eventually, Walker convinced Gabe to suit up again, and the teenager said it “helped me get a lot of this anger out, and it helped me be closer to my dad.”

Inspired by former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick, he decided to kneel during the national anthem. “It felt good to take a knee,” he said.

His junior year, Murphy transferred to a school in a conservative suburb of Sacramento and said he had friction with the coach in part because of his desire to kneel, and ended up not playing that season. The school district said that he was never on the team and that its current policies allow kneeling.

He ended up being home-schooled the remainder of that year after his mother was in a car accident, but he said he mostly stayed inside, passing time with PlayStation football and a job at a mall hat store, trying to help pay bills when money was so tight they couldn’t buy food.

“That was my whole junior year down,” Gabe said. “I lost it. I don’t get another chance.”

He dropped from 215 pounds to 160, and when he transferred to another school for his senior year, he wasn’t a starter anymore. But he decorated his cleats with his father’s name and had a sticker against police brutality made for his helmet.

When he saw the Floyd video, he couldn’t help but compare it to his father. He is frustrated that Christopher Murphy’s case has not received attention. “I just don’t understand how everybody knows about [Floyd] and not my dad,” he said.

He credits the teenage girl who recorded video of the Floyd incident for bringing it to light, and ultimately for the charges the four involved officers now face.

“That was really brave of her to stand right in front of the cop and do that,” he said. “At least the people got in trouble for what happened.”

The district attorney who investigated Murphy’s case found the officers had acted within policy and law, and the CHP has not publicly released the video.

With the coronavirus closings, Gabe is not sure if he will go back to finish school, but he dreams of ways to get back into football. He refuses to regret where grief has taken him.

“I was trying to find my way, and the best way for me,” he said. “Maybe it wasn’t the best way, but it was the way I took.”

Lisa Vargas, mother of Anthony Vargas

Lisa Vargas lost her son nearly two years ago, but still, she knows so little about how or why he died.

Anthony Vargas left his East L.A. home one summer night for a barbecue. Hours later, after a scuffle with sheriff’s deputies, he lay lifeless on a blood-stained patch of grass. He was 21.

His death transformed Lisa Vargas, turned her into a community activist, a part-time detective, a determined mother who spends her free time pushing to prove that deaths like her son’s — at the hands of law enforcement — are preventable.

According to deputies, Anthony Vargas got caught up in a search for three robbery suspects. Investigators do not think he was involved in the robbery but allege he ran from authorities and resisted attempts to handcuff him.

Deputies allege the young man pulled a gun from his waistband. After a struggle, they shot him.

His mother said officials have changed their story several times. She said her son had no criminal record and had never owned a gun.

He was active in church, loved hosting barbecues and used to take neighborhood kids fishing at the Santa Monica Pier. One Fourth of July, he spent a portion of his savings, close to $1,000, to buy fireworks for his siblings, nieces and nephews.

“They took someone who was trying to help the community and destroyed him,” Lisa Vargas said. “Then they tried to slander his name and make him sound like a criminal.”

Vargas has filed a civil suit and, through an attorney, fought to collect information. Authorities declined to comment on the case.

After her son’s death, Vargas bonded with other mothers in the East L.A. area who have lost their sons to police killings. The group began with about seven women and has grown to 15 as deaths have continued. Some of the families, Vargas said, feel intimidated to speak: They struggle with limited English, their immigration status, a lack of hope. Some fear being judged on social media.

Vargas, a leader in the group, tells them: “It’s OK. If you don’t want to go out there and shout your son’s name, we’ll do it for you so his name is not forgotten.”

In recent days, she’s followed the Floyd protests closely, hoping the greater message about police brutality is not lost in all the coverage about violence and vandalism. She hopes this moment creates concrete changes: better police training, more transparency, more support from government officials.

“Money cannot repair what they’ve done to us; therapy cannot repair it; not even convictions can compensate a life,” Vargas said. “They took our futures, our family. They need to understand why the community is in an uproar.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.