Column: Teaching the coronavirus outbreak in Los Angeles as a crash course in crisis management

Crises disrupt. Crises test us. Crises force us to find new ways to function on the fly.

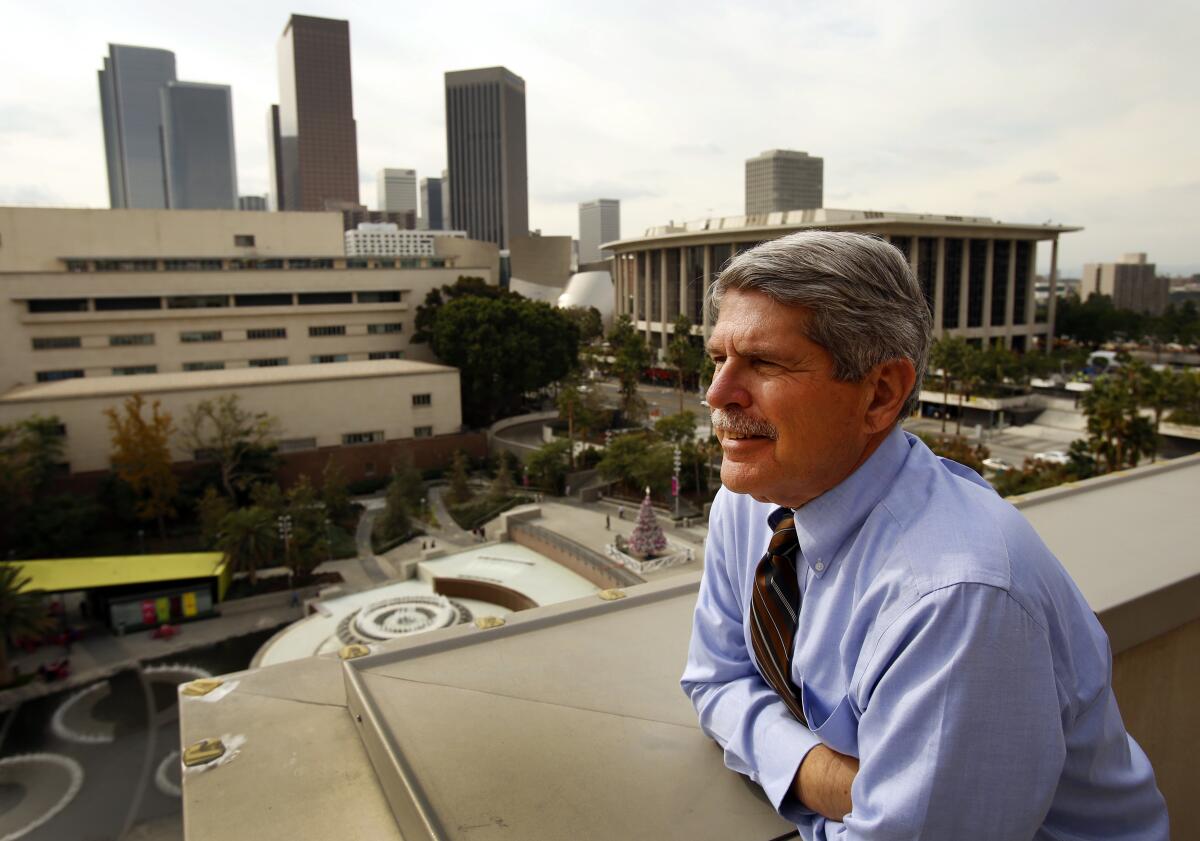

Zev Yaroslavsky knows this. How could he not after nearly 40 years in public office in Los Angeles?

The former longtime city councilman and county supervisor, who was at the center of our region’s every major moment for so long, knows just how much a crisis can teach us — about who we really are and what we need to care more about and what we have to do better and do differently.

So in April, at UCLA’s Luskin School of Public Affairs, right as students were showing up on Zoom to take it, he scrapped his plans for the graduate-level seminar he’s been teaching for the last four springs on the leaders, institutions and interests that shape Los Angeles’ civic policies and quality of life.

Once the coronavirus arrived, he told me of his usual curriculum, “I thought to myself, this doesn’t make sense. It feels trivial.”

So out went the old syllabus. In came a new one — a crash course in real-time Los Angeles coronavirus crisis management.

Yaroslavsky, 71, reached out to me to tell me about his class after I wrote in my column last week that in my ideal high school right now, I’d make the pandemic the textbook for everything.

That’s how he feels too, he told me, about the educational power of this time we are living in.

“There comes a moment when you can change the trajectory of a student’s life,” he told me. “This can be that moment.”

If you’ve lived in Los Angeles any length of time, you know those sharp brown eyes, you know that mustache, you know that blunt, sometimes gruff, no-nonsense voice. You may have wondered where all that energy was going since Yaroslavsky termed out after five terms as a supervisor in 2014.

In fact, he’s still a part of many a civic discussion — and is making good on his strong commitment, through his alma mater, UCLA, to share his vast experience with the next generation of leaders.

Ordinarily in the spring seminar, Yaroslavsky and his former chief deputy and co-teacher, Alisa Belinkoff Katz, might draw on their vast contacts to bring in a city planner to talk about land-use policy, a prominent journalist to discuss how media coverage influences the public debate, the head of the L.A. Opera to talk about the role of arts and culture in the city.

In this new version of the class, L.A. County Supervisor Kathryn Barger spoke to the class in early April fresh from her televised daily coronavirus briefing.

Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas showed up to talk about efforts to help homeless and other marginalized communities in the crisis.

Elan Shultz, senior health deputy first for Yaroslavsky and then for his successor, Supervisor Sheila Kuehl, who is now on loan to the county’s Department of Health Services to serve as its COVID-19 community testing manager, spent more than two hours talking passionately about the many challenges — led by a lack of centralized federal leadership — complicating the public health response.

Los Angeles tenants advocate Larry Gross, executive director of the Coalition for Economic Survival, broke down for students the many ways in which the coronavirus crisis was rapidly exacerbating an already extreme crisis in housing affordability.

And each week Yaroslavsky has shared his own wisdom in analyzing the fast-changing government response to the virus.

Recently, he talked to students about the constant balancing act of Gov. Gavin Newsom, Mayor Eric Garcetti and other public officials as they keep reiterating that they are going to be guided by science and data while simultaneously laying out plans to slowly loosen restrictions, offering a light at the end of the tunnel.

Older Americans deserve our protection from coronavirus. They want to get back to their busy lives, too

Any crisis, he told them, had a tipping point, when public sentiment would shift directions. For now, Californians mostly were willing to follow the new rules — but chances are that pretty soon, many of them no longer would be. Leaders have to pay close attention to those shifts, which can lead to a sudden lack of support, he said.

“There’s a fine line between being a leader and being a loner,” he told the class. “If you’re trying to lead and you have no followers, you’re a loner.”

The spring seminar, Yaroslavsky said, usually attracts students in such fields as urban planning, public health and environmental science who want to go into some form of government or nonprofit work.

What better way to counterbalance their theoretical and quantitative training than to show them real-world, life-and-death decision-making in the moment?

And what else could his students really be expected to concentrate on fully but the pandemic? In the first weeks, he learned that three of them already had come down with the virus.

One was Dulce Vasquez, 34, who works full time for Arizona State University and is about to graduate with a master’s in public policy. She got sick in March and lost her sense of smell and taste, before that became a well-known symptom of the virus and before testing was widely available.

Asked why she took the seminar, she answered “Zev,” whom she described as an L.A. icon. “I was going to take his class regardless. He could teach me how to make a pretzel. That would be great,” she said. But what he’s been teaching her in this retooled seminar has gone beyond even her high expectations, she said. “I think the creativity and the work it took to shift the curriculum has been amazing.”

Spike Friedman, a former sports journalist who is getting a master’s in urban planning with a focus on housing policy, told me, “I think this class has been particularly well suited to the moment. It’s not the easiest time to concentrate on schoolwork. This has been my most engaging class this quarter. What you’re getting is up-to-the-second, really relevant information.”

Jason Ballou, 46, who simultaneously is pursuing master’s degrees in public policy and social welfare, said he briefly thought about dropping the seminar when he learned that its focus had shifted to the coronavirus.

“I thought, oh my gosh, I’m so sick of the coronavirus,” he told me. “That’s really all we’re going to talk about?”

But then Barger appeared before the class from her office, straight from her briefing, at the tail end of an already long day. Zoom somehow made the moment especially intimate.

Talking to the students while alone in her office, Barger took off her glasses and rubbed her eyes and the bridge of her nose. He wears glasses too, Ballou told me, and recognized in these small gestures just how tired she must be as she talked about her fears of the virus’ impact on those who are in the country without legal permission, as well as those who are stuck at home in abusive situations.

Ballou, who wants to help people in need, grew up in a small town in the Midwest where cynicism about politicians and public servants ran deep. In that small, personal moment, he saw a very different, life-choice-affirming reality.

“You could see how exhausted she was and how much she cared,” he said. “It doesn’t get any more real than that.”

Or any more likely to form a lasting impression.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.