Zev Yaroslavsky, victim of term limits, reflects on decades in office

A decade into his long, public career, Zev Yaroslavsky ruminated about his motivation for first seeking elected office. “To save the world,” he told an interviewer in 1985.

A member of the Los Angeles City Council at the time, he conceded that he might need to settle for making local government work better. “That wouldn’t be the worst thing either,” he said.

As his nearly four decades in political office and five terms as a Los Angeles County supervisor end Monday, Yaroslavsky can at least lay claim to the latter goal. Engaged in most major public policy fights in Los Angeles over the last 40 years, the onetime student radical came out on the winning side much of the time.

He helped curtail police spying and the sometimes deadly chokehold once favored by Los Angeles police. He greatly reduced high-rise development citywide and joined a successful campaign against oil drilling in Pacific Palisades.

He was at the forefront of efforts to preserve more than 21,000 acres of open space in the Santa Monica Mountains, create a dedicated, 14-mile busway across the San Fernando Valley and convince voters to raise their taxes — to expand light rail, save the county’s trauma care network and improve public spaces such as the Hollywood Bowl.

Gruff and sometimes obstreperous, Yaroslavsky never pursued his onetime dream of running for mayor of Los Angeles.

He struck some constituents as being overly cautious, not going far enough to control traffic congestion or to impose civilian oversight on a sometimes violence-prone Sheriff’s Department. It took years, and a Los Angeles Times investigation, to finally get him and other county supervisors to confront substandard care of patients at the county’s Martin Luther King Jr./ Drew Medical Center.

Still, Yaroslavsky, 65, endured to become an elder of the region’s political class, whose counsel and endorsement were sought by two generations of would-be leaders. A liberal Democrat, he often joined with the board’s conservative Republicans to control spending, particularly employee pay. The supervisors’ fiscal discipline left the county without the perennial deficits and service reductions that have confronted his former colleagues at Los Angeles City Hall.

Former Mayor Richard J. Riordan, a Republican, said Yaroslavsky had been a fabulous partner and credited him with “standing up to unions” to protect the county treasury.

Supervisor Don Knabe, another Republican, recalled his early surprise at Yaroslavsky’s approach to board business. “I expected him to be a liberal zealot of sorts who just wanted to spend money,” Knabe said. “It was quite the contrary. He had to have discipline, like the rest of us, to afford programs that were important to him, like the Hollywood Bowl and Music Center” and a housing and support services initiative for the homeless.

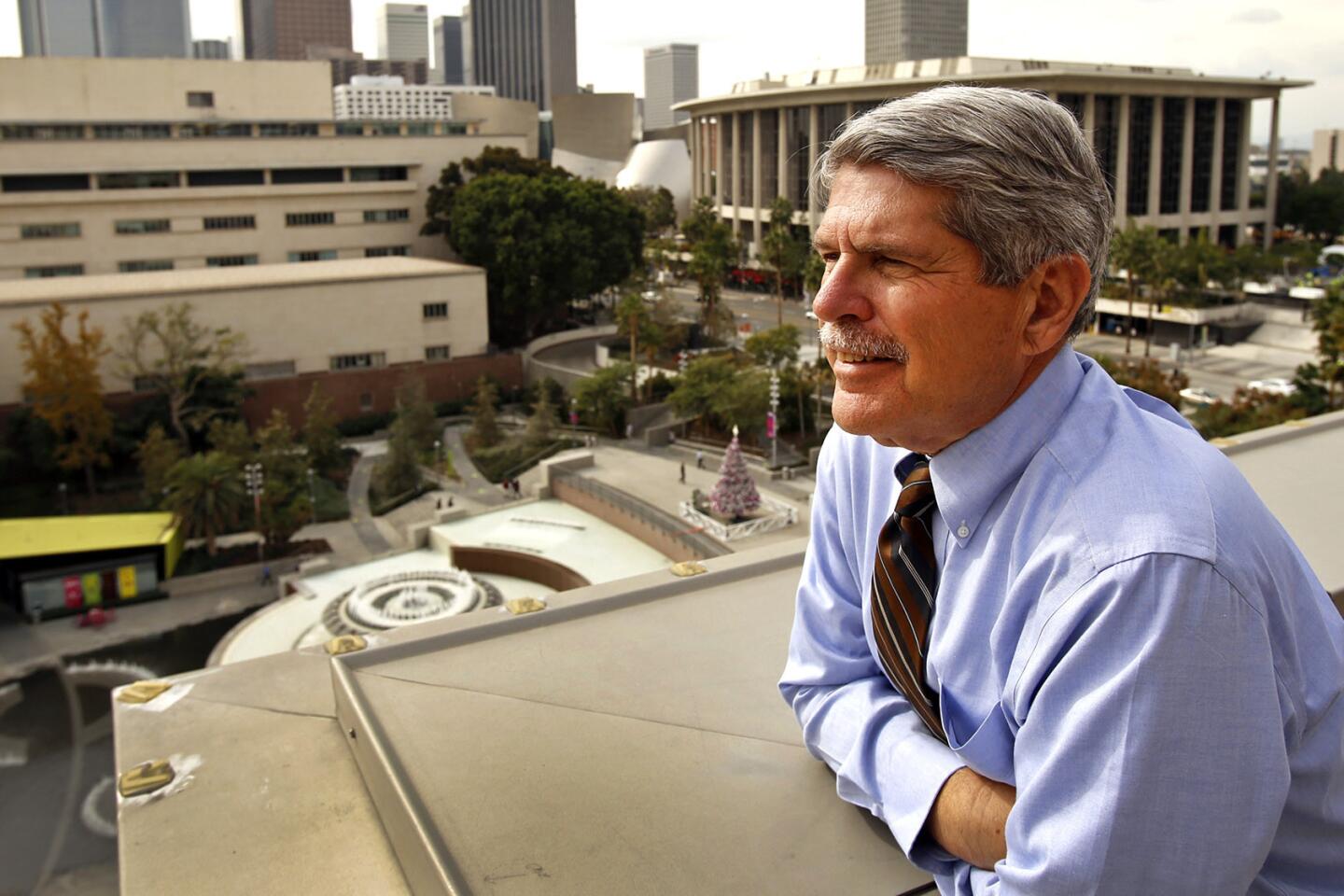

Cardboard boxes filled with mementos, files and photos surrounded Yaroslavsky as he recently reviewed a career that began when Gerald Ford was president. Nearly a thousand people attended a going-away tribute this month at Disney Hall. Dodger broadcaster Vin Scully — the only man in Los Angeles with a job Yaroslavsky said he coveted — quipped via video that the retiring politician would have a better chance doing radio for the minor league Great Lakes Loons.

Yaroslavsky said he is ready to move on from the county Hall of Administration, if not eager to surrender the power to confront issues affecting millions of Southern Californians as one of five legislator-executives running the largest local government in America.

“There are few positions in this country that give you the opportunity to make a difference as much as you can as a county supervisor,” Yaroslavsky said. Only the mayors of Chicago and New York wield such broad authority, he noted, pointing out that the mayor of Los Angeles — with no direct power over hospitals, schools, jails and more — has less clout. That was part of the calculus last year, he said, when he decided — once again — not to run for mayor.

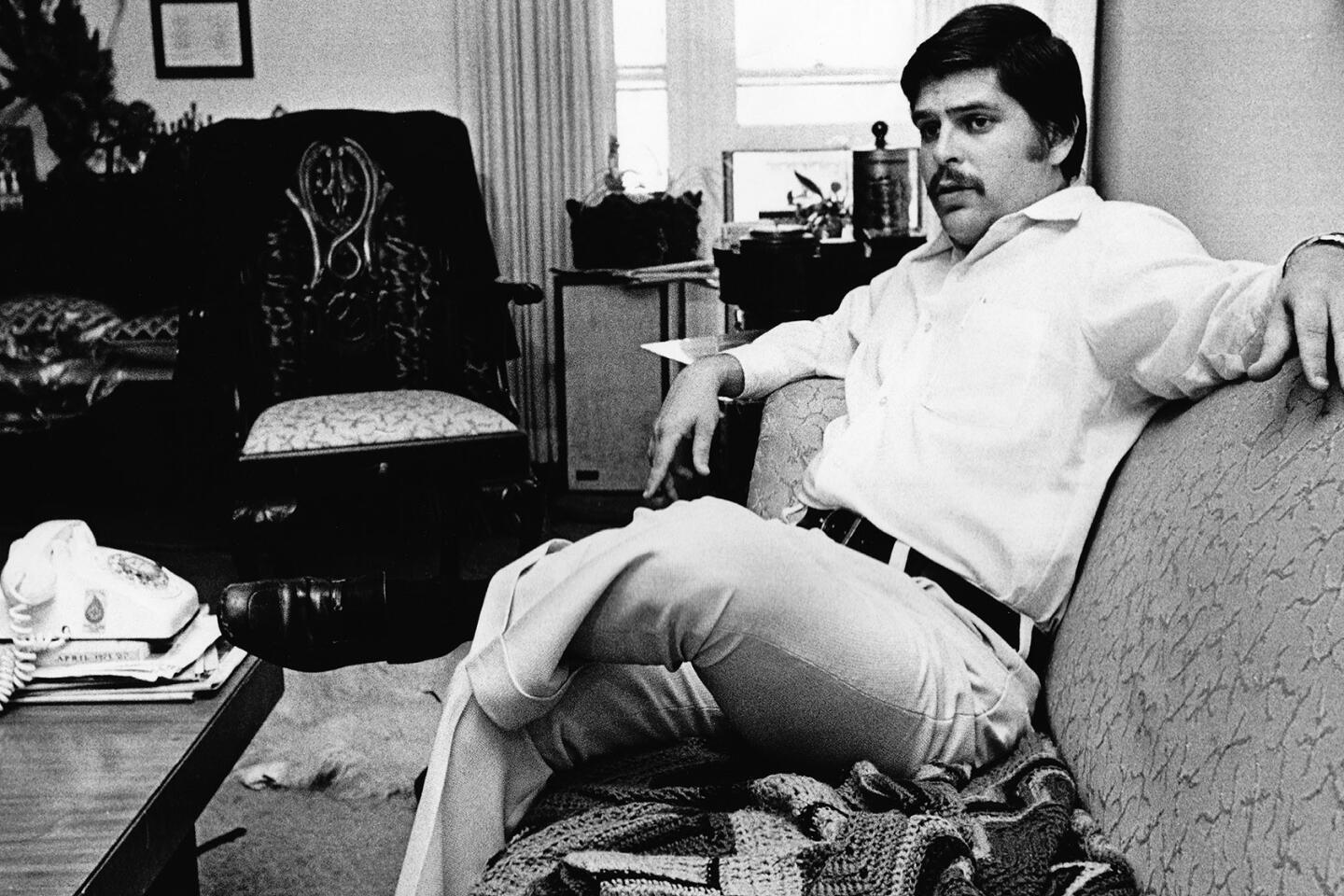

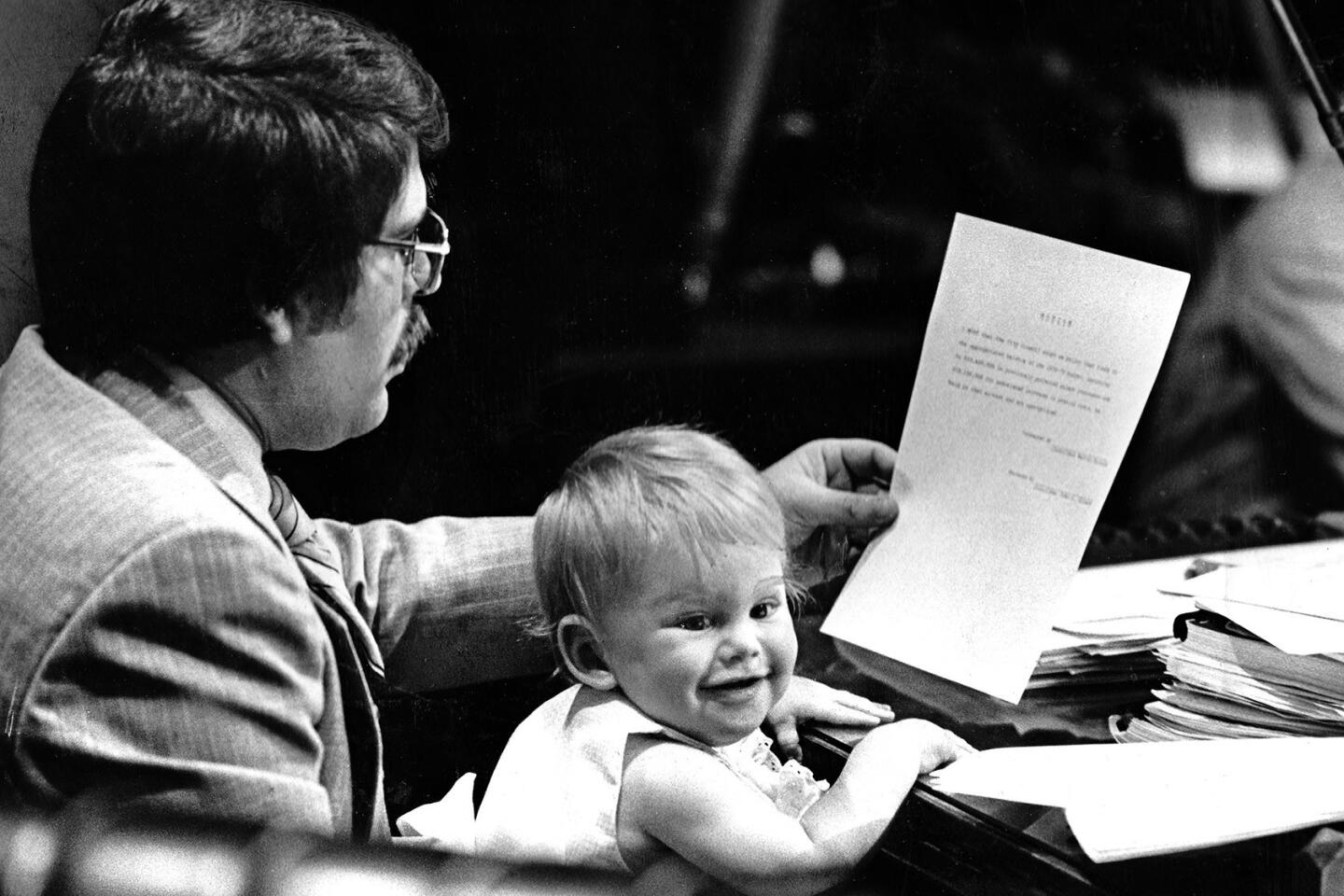

Yaroslavsky grew up in what was then a thriving Jewish enclave in Boyle Heights, the son of Russian immigrants and ardent Zionists who taught him “when someone needs help, you help them.” He attended Fairfax High School and UCLA, where he led protests against the treatment of Jews in the Soviet Union. He ran for City Council at the age of 26 and his victory over an ally of Mayor Tom Bradley stunned the city’s political elite.

When Bradley quipped that Yaroslavsky had become part of the establishment, Yaroslavsky reportedly retorted, “Yes, but the establishment is not part of me.”

Council colleagues initially viewed him as brazenly ambitious. When controlling overdevelopment became his mission, fellow city lawmakers and some constituents depicted Yaroslavsky as a vote-grabbing opportunist.

A later Times analysis found that while the councilman supported anti-growth laws, he quietly worked to support some projects — such as the Westside Pavilion shopping center — that he attacked in public.

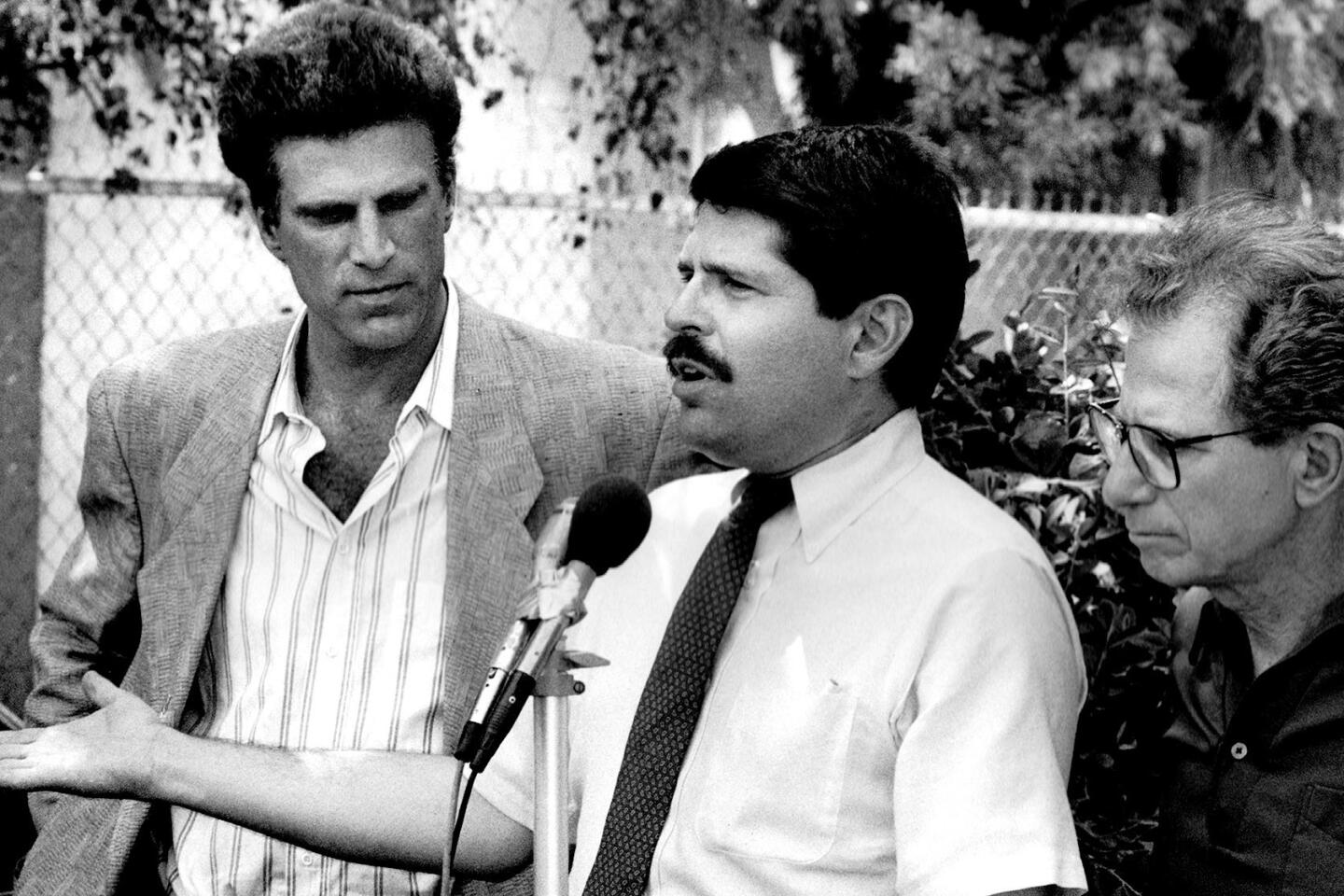

Yaroslavsky’s biggest win for the slow-growth movement came in 1986, when he joined Councilman Marvin Braude in crafting and winning ballot box approval of Proposition U. The populist measure, a landmark in Los Angeles’ development wars, reduced by half the allowable size of new buildings on roughly 70% of the city’s commercial property.

By 1989, Yaroslavsky appeared strongly positioned to challenge Bradley, whose popularity had waned. He created a campaign organization and raised a substantial war chest before deciding Bradley couldn’t be beaten. Some faulted Yaroslavsky for a failure of courage, but he still insists he made the right call. “I wouldn’t have accomplished a fraction of what I have done here at the county,” he said.

The pathway to an eighth-floor suite in the county Hall of Administration opened wide when Supervisor Ed Edelman retired. Yaroslavsky faced only token opposition in the district, which stretches from the Westside to the heart of the San Fernando Valley.

On the day in 1994 that Yaroslavsky was sworn in as supervisor, Orange County declared bankruptcy. Yaroslavsky, who burrowed into the intricacies of government budgeting as City Hall’s finance committee chairman, feared that Los Angeles County, with spending exceeding revenue by about $1 billion a year, could also face insolvency.

He became part of a majority that held the line on most salary increases, earning the enmity of organized labor. During the Great Recession and its aftermath, county employees went at least four years without a pay increase. Down the hill in the Civic Center, city officials exacerbated their budget deficits by granting a five-year, 25% salary increase to workers on the eve of the economic downturn.

Yaroslavsky’s concern about the spiraling costs of subway construction in the 1990s prompted him to sponsor Proposition A, a ballot measure requiring transit sales tax revenues to be restricted to bus and light-rail projects. His proudest achievement, he said, was completion of the relatively low-cost 14-mile Orange Line busway from North Hollywood to Warner Center. Its 33,000 daily ridership has exceeded projections.

Yaroslavsky pushed for tax increases for basic services when he saw no alternative. When budget shortfalls threatened to shut down emergency room trauma units, he wrote and campaigned for a property tax increase that kept the system operating.

Despite his political roots on the left, Yaroslavsky at times bucked liberal-progressive orthodoxy. In 2011, he fought a plan by fellow Democratic Supervisor Gloria Molina and others to redraw his district to create a second supervisorial district with a Latino majority. Other communities of interest would have been broken apart by the plan, he argued.

There is broad consensus about one major failure of the county board in the Yaroslavsky era: the crisis in care at the now-closed King/Drew Medical Center. In an interview, Yaroslavsky said there is “no way to put lipstick on that situation.” For too long, he said, he and other board members deferred to the elected supervisors whose district included the South Los Angeles hospital.

The 2004 Times investigation found widespread breakdowns in care and timid action by top county officials. With the anticipated opening of a new Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital early next year, Yaroslavsky said the Board of Supervisors needs to view it first as a county healthcare facility and only secondarily as a job creator and economic engine for a poor community. “We can’t slip back,” he said.

In his final days in office, Yaroslavsky packed boxes, preparing to be without an elected position for the first time since 1975. Weeks earlier, he won praise from homeowner groups after the California Coastal Commission accepted a plan he backed to preserve open space and limit development in Santa Monica Mountains near Malibu.

Yaroslavsky said he expects to remain politically active on issues such as public pension reform and will write a memoir and possibly teach at a local university.

He also plans to work supporting democracies overseas. Dozens of photos with celebrities and world leaders lined his offices’ hallway. One pictured women waiting hours to vote in a 2011 Nigerian election, which he helped monitor as an international observer. “The most exhilarating experience I’ve ever had,” he said.

Yaroslavsky does not like term limits, including the one forcing him to leave office. But “40 years is enough,” he said. Most of the men in his family did not live to 70, he added.

“I have accomplished what I set out to accomplish, and then some,” he said, adding, “I want to walk out of here, rather than be carried out.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.