They spotted the man’s naked face in the frozen food aisle.

And in the age of COVID-19, it seemed positively indecent.

The way he perused the freezers, nose and mouth uncovered, as if a virus weren’t floating around, raring to kill. Shoppers stared. A worker who was guiding customers to each checkout lane rushed to tell the store director, who quickly found the outlier.

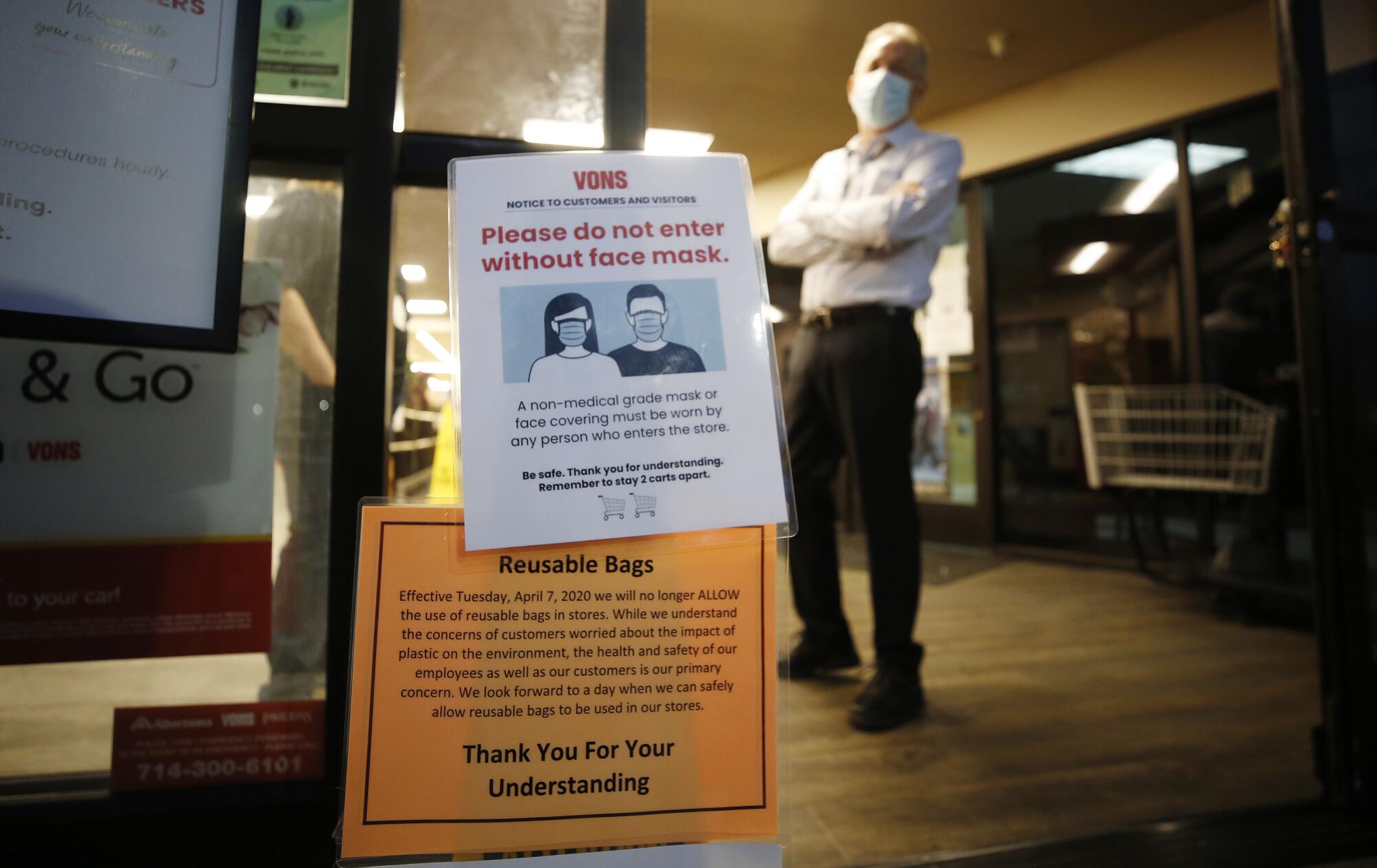

“Excuse me, sir, but you need to have a mask to shop in this store,” Dan Graves said.

The man explained he had one in his backpack, which he’d placed inside a shopping cart. He pulled out his black mask, as if seeking absolution.

“You need to put it on,” Graves said firmly.

“You know what, just forget it,” the man snapped. As he headed for the door, he tried to get in the final word: “You must be a Democrat!”

“Have a nice day,” Graves responded.

For the last few months, grocery stores, deemed essential businesses, have served as public theaters for the traumatized American consumer.

Thrust into the role of front-line soldiers amid a war against the coronavirus, employees have had to manage panic attacks, cursing, near-fights and counseling sessions at the checkout stand. They’ve been threatened by customers who are angry about having to wear masks.

Some workers have received an hourly bump in appreciation pay. A growing number across the U.S. have become ill. Dozens have died.

At the Vons grocery store on Crenshaw Boulevard in Torrance, cashiers have watched the installation of Plexiglas shields and the formation of lines that snake around the aisles. They’ve seen people shove fellow customers’ purchases back on the conveyor belt and then demand all new food because someone touched theirs.

Unlike the customers they serve at this 76,000-square-foot store, the 165 employees — who are dealing with some of the same feelings of uncertainty and anxiety — cannot shelter at home.

On a recent Monday, under a muddy night sky, a cashier rang a doorbell at the front of the store, signaling her arrival. A Naked juice truck pulled around back to drop off its supplies. It was 5 a.m., and the store was already busy.

Anthony Capone wiped dozens of black shopping carts with disinfectant.

In the produce department, a worker picked out Gala apples, onions, Roma tomatoes and oranges and then piled them on a cart to fill half a dozen online delivery orders. The store has hired 30 extra employees as demand for these deliveries has increased.

Sonia Burgos, the store’s inventory control clerk who’d started her day at 4 a.m., waited for vendors and truck drivers in the receiving zone. She had every vendor review the same questions — Do you have any symptoms? Coughing, shortness of breath? Sore throat, chills or body aches? — before they signed in on a “Vendor COVID-19 log.”

At checkout Lane 3, Miyoshi Lampkin gripped a bottle of orange-colored disinfectant and coated the black conveyor belt, registers and separators. Sanitizing her station has become as routine as brushing her teeth.

Lampkin, who has worked at the store for 21 years, prepared for the start of her shift with a tall coffee from the Starbucks inside the store. That’s all the caffeine she’d need for the day.

“My adrenaline is off the people. I love people,” she said. “It keeps me going.”

Shortly before 6 a.m., Capone, a front-end supervisor, positioned himself at the sliding front doors to welcome at-risk shoppers and seniors 60 and older.

“Morning folks, how are we doing today?” Capone asked, speaking through a brown mask. He recognized one of his regulars, 75-year-old Diane DeWeese.

“Two minutes, countdown,” said DeWeese, who has been coming to this store for nearly two decades. She was one of only two people waiting out front. Just a few weeks ago, she recalled, the line stretched down the street.

When it was time, Capone welcomed the two customers inside and directed them to the sanitized carts.

“One toilet paper, one paper towel,” he reminded them. “You guys have an awesome day.”

It was Capone’s responsibility to check identification for that first hour, to make sure it was seniors entering. Within 20 minutes, he had turned away two people.

He listened as customers echoed the same frustration the employees were experiencing.

“Ugh, I’m so sick of this,” Kathi Wilson groaned behind her floral mask, in response to Capone’s question about her day.

Wilson has asthma and has spent nearly every day at home since the beginning of the outbreak. It’s hard, she said, to live through something with no end in sight.

“I know,” Capone responded. “Hang in there.”

One of the first shoppers made a beeline to Aisle 11, where at least 20 plastic-wrapped 12-packs of Charmin Ultra Soft and Cottonelle Ultra CleanCare toilet paper and dozens of rolls of Bounty and Viva paper towels graced the shelves, courtesy of a shipment the night before.

At checkout Lane 5, soap opera digests gave no indication of a pandemic. But the magazine rack to the left of the conveyor belt was filled with reminders. Time announced that we are not alone, People offered COVID-19-inspired acts of kindness, and Los Angeles magazine featured a woman in a blue medical mask with the words, “Now what?”

“Hi, how are you?” Debbie Alexander asked, her voice bright, as she scanned a customer’s Scott toilet paper and paper towels. After 40 years, Alexander knows exactly where every bar code is placed.

“Good,” her customer responded. “Better yet, I found paper towels.”

“You found gold today,” Alexander said, as she laughed through her mask, decorated with Disney’s Belle and her prince — after he’d transformed back into a human, after the nightmare ended.

Despite Alexander’s cheerful exterior, she says at times she uses breathing exercises to help keep herself calm. Her husband has a heart condition, diabetes and high blood pressure. She was terrified she might bring the virus home.

“But it’s my job,” Alexander said. “There’s nothing I can do.”

Work was already tough enough before the outbreak. Many of the store’s nearly 200 employees are part time. The union pay scale goes from state minimum wage to $21.42 an hour. Cashiers who are constantly swiping bar-coded items sometimes suffer from carpal tunnel syndrome. They rely on Dr. Scholl’s shoes and foam mats at their check stands to ease the aching in their knees.

But in March, when the orders to shelter at home were announced, cashiers started to suffer from panic attacks as customers flooded the store. Alexander’s anxiety still flares up when she thinks back to March 13 — a day she calls “apocalypse Friday.”

Every register was open; lines stretched back to the meat department and branched off into produce and the bakery. It took 30 to 45 minutes for customers to reach the checkout lane. One customer in the express lane placed $850 in groceries on the conveyor belt.

“We had no idea this was going to happen,” Alexander said. “People were just buying groceries like they were never going to see them again.”

She likened the aftermath of her 10-hour day to the scene in the movie “A Bug’s Life,” when the grasshoppers came “and ravaged the place and there was nothing left.”

Alexander worked 19 days straight in March. Albertsons Cos., which owns Vons, announced a temporary $2-per-hour increase in pay, which started March 15. The Plexiglas didn’t go up until the end of the month.

“People’s nerves were so on edge the first couple weeks,” Alexander said.

But it wasn’t all bad. There was the customer who paid for a woman in front of her after she struggled to find her money. The one who offered Alexander $20 as a thank you — which the cashier gently declined. Local businesses bought lunches for employees or donated Starbucks gift cards.

Thank yous were not something cashiers heard all that often before the outbreak. Now, Alexander said, she gets thanked every day. Real thank yous that mean something at a time when she can’t hug her grandchildren or visit her 82-year-old father, who recently had a heart attack.

Still. Every day is filled with stress and uncertainty.

Vons employees have slept apart from loved ones, stripped down before entering their homes and sprayed shoes with Lysol after their shifts. They worry about elderly family members and children at home.

“Being in here all day, you just don’t know who’s sick and who isn’t,” Alexander said. “You do worry about what you’re bringing home and who you’re going to infect.”

In the middle of the morning, Lampkin walked into the break room, the space where workers can remove their masks to eat and heave deep sighs of relief. It was time for her lunch, a temporary reprieve from the constant beep of the bar-code reader.

She washed her hands and popped two White Castle jalapeño cheese sliders into the microwave. As she waited, Lampkin wiped down the table and seat.

“Sonia, what do you got,” Lampkin called out to Burgos, who sat across the room, alone.

“Turkey sandwich with sourdough. And fruit,” Burgos said.

Before the outbreak, they would have been sitting together. But the seat across from Lampkin was blocked with a strip of caution tape, and a yellow sign on the wall read, “One person per table social distancing.”

Nearby, Kelley Talleda, a courtesy clerk, waited in a booth for her shift to start.

When everything began, Talleda said, they worked longer shifts and had to guide the customers through all the new rules.

“One of my customers said it best: ‘Not a pandemic — a panic,’” Lampkin said. “If you have an earthquake, you get a crowd of people for three days. But this has gone on and on and on.”

By 10:05 a.m., Lampkin’s phone timer went off — her 30-minute lunch break was over. She threw out her trash, washed her hands and went back to her register.

Burgos lingered a little longer and chatted with a co-worker at a neighboring table. They wondered if Mother’s Day weekend would be busy.

“Nobody’s going to be celebrating anyway,” Burgos said.

In the middle of the afternoon, customers continued to wait in line, standing on red markers that thanked them for practicing social distancing and reminded them to stay two carts apart. They were directed one way down the aisles to prevent crowding.

Customers included nurses, doctors and ambulance service workers. Some of them wore plastic face shields and gloves; others, just flimsy paper masks.

Antoinette Villegas directed a couple to checkout Lane 5. They glared at her when she asked if one of them could wait at the front of the store while the other made their purchase. She’s been cussed out a few times when she’s made the same request.

“We sleep in the same bed,” one man said.

“Yeah, but we don’t sleep in the same bed,” Villegas said.

Coldplay’s “Clocks” played on the store’s sound system, with lyrics that seemed especially relevant: “Am I part of the cure or am I part of the disease?”

Later in the day, as the crowds diminished, all but two of the checkout stands were closed. A customer who arrived with a coupon for a free four-pack of toilet paper was told the store had run out for the day. The cheeses were gone too, as well as the pasta.

Frank Morisaki, who has worked at the store for 16 years, scanned items for one of the last customers. Closing time was at 9 p.m.; the following week, it extended another two hours.

“You guys take care, be careful,” the customer said to Morisaki, before she stopped on the way out to grab a sanitizing wipe.

Morisaki tapped elbows with longtime customers and joked with them when he could. He listened to shoppers who had lost jobs and offered sympathy. And he was grateful for the customers who thanked him for his work, despite dealing with their own hardships.

“That’s what keeps me thriving to keep coming and putting in overtime,” he said. “I feel like a superhero.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.