Despite probation approval, L.A. blocks release of at-risk juvenile offenders

Dorian Martinez was sure her son was coming home.

The 17-year-old had been held in a La Verne juvenile camp for three months for a probation violation, the latest in a string of them stemming from a years-old drug possession charge, she said. But with county and state officials trying to lower jail populations to reduce the risk of a coronavirus outbreak, her son seemed like the perfect candidate to be let out early.

Martinez’s son suffers from asthma severe enough to require nebulizer treatments, and his probation officer submitted a petition asking the court to release the teen early, according to Martinez and her son’s attorney. And Martinez had what she thought to be a trump card — a picture of her son posing next to Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey, who presented the boy with an award in 2018 after his quick thinking helped police capture a sexual assault suspect.

But last week, a Los Angeles County Superior Court judge blocked his release. The matter didn’t even see the inside of a courtroom, according to the boy’s attorney, who said the judge denied the petition without argument.

Despite concerns about how rapidly the coronavirus could spread in jails, attorneys and parents said juvenile judges have rejected numerous pleas for the early release of youths during the pandemic, even in cases supported by the L.A. County Probation Department. In some cases, the pleas came from juveniles who had an elevated risk of contracting the virus or little time left on their sentence, yet judges declined to even hold a hearing.

“They didn’t give me the opportunity to talk about my concerns. They didn’t give an opportunity to his probation officer or the camp to say why they want to send my son home now,” Martinez said. “They just ... threw it out. It’s kind of hard to understand right now, and I just don’t know what else to do.”

Concern about the spread of the virus in juvenile facilities has increased in recent days. The number of confirmed coronavirus cases among Probation Department employees jumped to 16 last week, officials said.

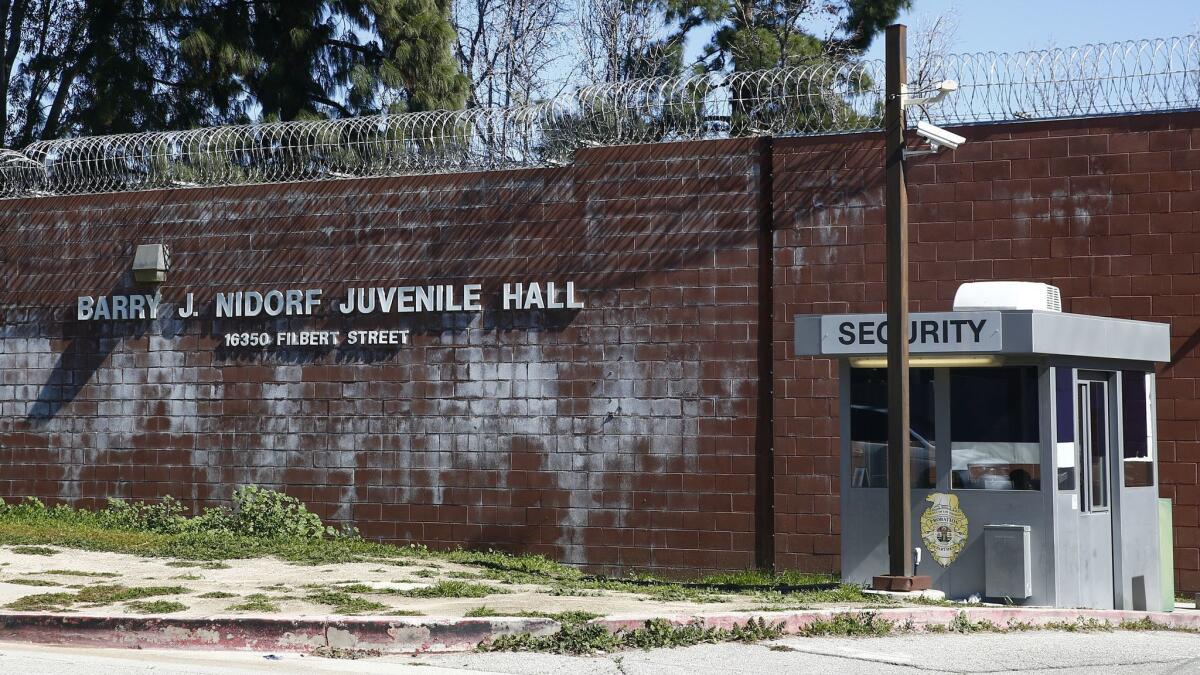

Five of those employees were assigned to the Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Hall in Sylmar, where 37 youths remain under quarantine because of potential exposure to the virus, officials said. The juveniles “are doing well and not showing any symptoms,” the Probation Department said in a statement.

Across California, elected officials have moved swiftly to lower jail and prison populations, hoping to reduce the risk of a rapid surge in coronavirus behind bars. In late March, Gov. Gavin Newsom ordered the early release of 3,500 inmates who had been convicted of nonviolent offenses and had less than 60 days left on their sentences. Hundreds of adults have been released from L.A. County jails under similar circumstances.

Nationally, advocates, attorneys and relatives of youths in custody have expressed frustration that similar efforts have not gained traction in the juvenile justice system, even as reports of outbreaks begin to pop up in youth facilities. On Friday, health officials confirmed that 25 juveniles had tested positive for the coronavirus at a facility outside Richmond, Va. Juveniles in custody have also tested positive for the illness in Maryland and Louisiana, according to published reports.

In recent weeks, L.A. County probation officials say they’ve made an effort to shrink the population of juvenile halls and camps, submitting to the courts a list of 59 young detainees to be considered for early release. The court released 39 of the youths and set an additional 27 free last week without the Probation Department’s recommendation, Adam Wolfson, communications director for the agency, said.

Ann Donlan, a spokeswoman for Los Angeles County Superior Court, said more stringent conditions must be met under California law to secure the release of young offenders.

“Unlike adult inmate release, the court cannot just release an underage person on their own recognizance,” she said. “The court and Probation Department are responsible to ensure that minors who have committed serious criminal acts have participated in rehabilitative treatment programs, are no longer a danger to themselves and others and will return to a safe home with a responsible parent or guardian.”

Last week, however, the California Department of Justice issued a bulletin noting that probation officials can release juveniles from custody during “an emergency endangering the lives of inmates,” seemingly offering a way around a judge’s refusal. Donlan referred questions about the bulletin to the Probation Department, which declined to comment.

Donlan also discounted concerns about petitions for release being dismissed without a hearing.

“Any motion without merit is denied,” she said, adding that judges who have made rulings from chambers were doing so to expedite the process.

Advocates and attorneys argue that there is no rehabilitative value in continuing to detain youths, as most educational and counseling programs have been stalled because of the coronavirus. Advocates also contend that bench rulings, especially those involving cases of juveniles with health issues, amount to due process violations.

“The judge isn’t being forced to put their justification on the record, and that’s a problem,” said Tim Curry, legal director of the National Juvenile Defender Center in Washington D.C. “‘Because I said so’ shouldn’t be the standard during a national crisis.”

Defense attorney Rachel Steinback expressed similar frustrations when one of her clients was denied early release on April 10. The client, an asthmatic 17-year-old with less than five weeks left in custody for a nonviolent property crime, had the support of his probation officer when Steinback petitioned for his release.

Steinback said the teen became concerned earlier this month when another juvenile at Camp Afflerbaugh got sick and was removed from the facility. Her client has been puffing on his inhaler frequently as a precaution and clung for a week to the lone paper surgical mask he was provided by probation officers, before throwing it out after it became “disgusting.”

“Unless there’s a danger to society, they should absolutely let him go home,” she said. “But the fact that the camp probation officer is supporting his release, and the fact that the judge is still refusing to release, is an outrage.”

The teen’s probation officer has filed a separate motion seeking his release, Steinback said.

Defense attorney Ed Geil said he expected his 15-year-old client would be heading home from Camp Kilpatrick in early April. The teen had served about five months in a juvenile camp after being sentenced to up to seven months in custody for a nonviolent property crime, Geil said. Probation officials supported his release and even said they had received a court order allowing him to leave the camp on April 3, according to an email reviewed by The Times.

Instead of walking free, the youth was ordered by a judge in Inglewood Juvenile Court to be detained until a May 1 hearing, Geil said. The teen had received some negative reports inside the juvenile camp in recent weeks, but Geil said the camp director still supported his release.

“What the heck is going on here? Why are they treating these kids worse than adults?” Geil asked. “The director of the camp told me in the emails that we were sending back and forth that she was very surprised that this was going on.”

The population of L.A. County’s juvenile halls and camps has dipped sharply in the past six weeks. The number of youths in custody fell from 819 on March 1 to 590 on April 17, a drop of 26%.

It was not immediately clear how many of those releases were scheduled and unrelated to the coronavirus. According to the Probation Department, 605 juveniles remain in custody. About 246 of them are awaiting trial.

Some attorneys said juvenile judges aren’t taking the threat of the virus seriously.

“I have heard a juvenile judge say, on the record, that the evidence a juvenile is at increased risk from COVID-19 by virtue of being in the juvenile halls and camps is just speculative, and in the same breath say that we’re all at some level of risk anyway,” said Andy Bouvier-Brown, a criminal defense attorney who often represents juveniles. “Judges have pointed to the fact that there aren’t any confirmed positive tests of kids in the hall as evidence that they are not currently at risk.”

Last week, the Loyola Law School Center For Juvenile Law and Policy and the Independent Juvenile Defender Program petitioned the California Supreme Court to release a wide category of youths being held in L.A. County. The list includes any juveniles with a health condition that places them “at higher risk of” contracting the coronavirus, as defined by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; any juvenile exhibiting symptoms associated with the virus; and any youths being held on either a probation violation or failure to appear in court.

The petition also highlighted a courtroom logjam in L.A. County that may be slowing hearings for juvenile releases. Fewer than half of the county’s 18 juvenile judges are currently hearing cases, the court filing said. The petition also suggested that youths and their attorneys were being given little chance to plead for early release, even with the support of the Probation Department.

Both the Probation Department and a court spokeswoman declined to comment on the petition.

Jim Gregory, the attorney representing Martinez’s son, said probation officers also seem to be growing frustrated with some juvenile judges’ actions during the pandemic. After learning that Martinez’s son would not be going home, Gregory immediately called the teen’s probation officer.

“He was livid,” Gregory said. “He said people are dying; he’s got to get out of here.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.