Editorial: Juvenile probation failures have left L.A.’s troubled kids nowhere to go

It’s not at all clear what will happen if the Board of State and Community Corrections determines on Thursday that Los Angeles County’s two juvenile halls remain unsuitable for the confinement of youth.

The county has no place left to house, secure and care for nearly 300 juveniles, and besides, the problem is not so much the facilities as it is the inadequate number of staff who show up to work in them.

Los Padrinos, the county’s newest juvenile hall, is at risk of being shut down by state regulators after they found the Probation Department failed to comply with state regulations.

For the record:

12:52 p.m. April 8, 2024An earlier version of this editorial gave the wrong day for the meeting of the Board of State and Community Corrections. It is meeting Thursday.

If the county can’t care for its most troubled kids, can the state? Not anymore.

The state once ran the world’s most renowned juvenile rehabilitation program, the California Youth Authority, which was developed in the 1940s and operated in tandem with county-run juvenile halls and probation camps.

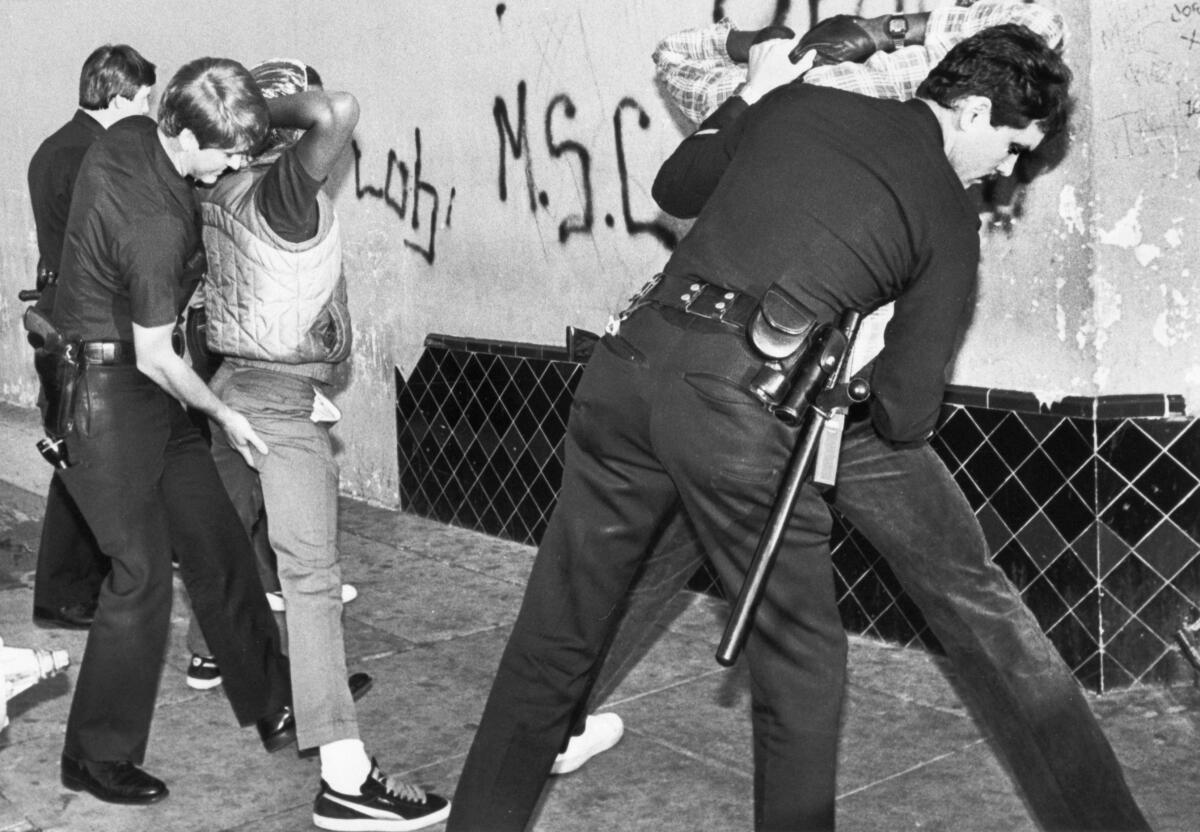

But the Youth Authority began to unravel with the 1980s shift in public attitude toward juvenile crime, panic over young supposed “superpredators,” and a ballooning number of arrests and gratuitously harsh punishments.

Eighty-one years after California incarcerated its first ‘ward,’ the state’s notoriously grim youth prison system is shutting down. But will young offenders fare any better in county lockups?

The program morphed into a network of cruel juvenile prisons, where youths were physically, mentally and sexually abused. Legal liability and payouts skyrocketed. Unable to meet its moral and legal obligation to safely house and rehabilitate young people, the state began to look for ways to offload them.

It first tried “realignment” — a sound strategy under which counties could no longer send the state its toughest juveniles free of charge. Counties now had a financial incentive to find more effective and efficient alternatives closer to home, often without detention. Youth crime, arrests and incarceration plummeted.

It is far too late for Los Angeles County’s juvenile probation operation to reform itself. It needs outside intervention that goes beyond oversight and license revocation.

The toughest cases remained with the state, which planned to transfer responsibility from its corrections department to human services, as befitting a program that by law does not impose punishment but provides rehabilitation and treatment.

But Gov. Gavin Newsom opted instead to get the state out of the juvenile justice business altogether, except for providing counties guidance, funding and enforcement of standards. The Youth Authority, which had become the Division of Juvenile Justice in 2005, shut down in 2023.

Los Angeles County juvenile halls have been cited for unconstitutionally poor conditions for decades. It’s too late to save them.

That brings us back to L.A. County and its current predicament. It had already been failing with its core population of juvenile wards, subjecting them to the same harmful conditions found in the state’s juvenile prisons — including sexual assault, mental and emotional torture, and physical abuse. The county, like the state, paid out costly legal settlements.

As the state prepared to transfer its remaining juveniles to the county, the Board of Supervisors spent much of 2021 and 2022 squabbling over where to put them. Some communities, including Malibu and Santa Clarita, took legal action to keep them out of local probation camps. The supervisors finally settled on a specially secured segment of the Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Hall in Sylmar, where most are currently housed.

Los Angeles County government’s unconscionable floundering endangers the lives of the teenagers the county is duty-bound to protect

The corrections board lacked jurisdiction over that portion of Nidorf last year, when it ordered the rest of the facility closed after it repeatedly failed inspections for safety, security and supervision. But the law has since changed. Now the remaining portion of Nidorf faces closure, along with Los Padrinos Juvenile Hall in Downey, which the county hurriedly reopened last year after century-old Central Juvenile Hall in Boyle Heights was deemed unsuitable to house young people.

The county has repeatedly demonstrated that it is not capable of safely and securely operating a juvenile hall, not because it doesn’t have the facilities — it has plenty of buildings — but because its Probation Department lacks the organizational culture, personnel and commitment to care for troubled youth.

It’s a problem decades in the making, and has persisted despite countless attempts at reinvention, with blue-ribbon commissions, reconstructions, reorganizations, realignments, and frequently ousted and replaced chief probation officers. The mess long predates the state’s ill-considered move to shirk direct responsibility for juveniles and send the tough cases back to the counties. But the transfer was a stress test L.A. County simply couldn’t pass.

If Los Angeles County’s juvenile justice program fails, it could take other promising therapeutic and rehabilitative response to behavioral problems with it, including the governor’s plans for San Quentin.

If the corrections board this week finds that the county has brought Nidorf and Los Padrinos up to snuff, the relief will likely be short-lived, until the next failed inspection. A state attorney general enforcement action also appears unlikely to solve the problems. So then what? No one knows.

The sad truth is that the entire state and county edifice of laws, policies and programs created to provide rehabilitation, education and care for the most troubled youths cannot provide them. Young people in Los Angeles County juvenile halls likely come out worse than they went in.

Half of L.A. County Probation Department juvenile division workers don’t come to work, and their unions resist change. The county should push forward and replace the division.

The atrocity is clouded by euphemisms such as “hall” or “camp” to describe facilities that are really jails. State and county policy is officially to provide a “homelike environment,” but it’s not any kind of home anyone would choose. Rooms are really cells, classrooms are human warehouses, and the day-to-day goal is not so much rehabilitation, as required by law, but just surviving without being attacked, raped or killed by fentanyl overdose.

The state’s other 57 counties aren’t having the same problems with juvenile probation. In Los Angeles County, though, the entire state-county system is a shameful failure. The kids who are ordered into it are in desperate need of rescue from their supposed rescuers.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.