An ex-con teaches other former convicts how to live life outside prison walls

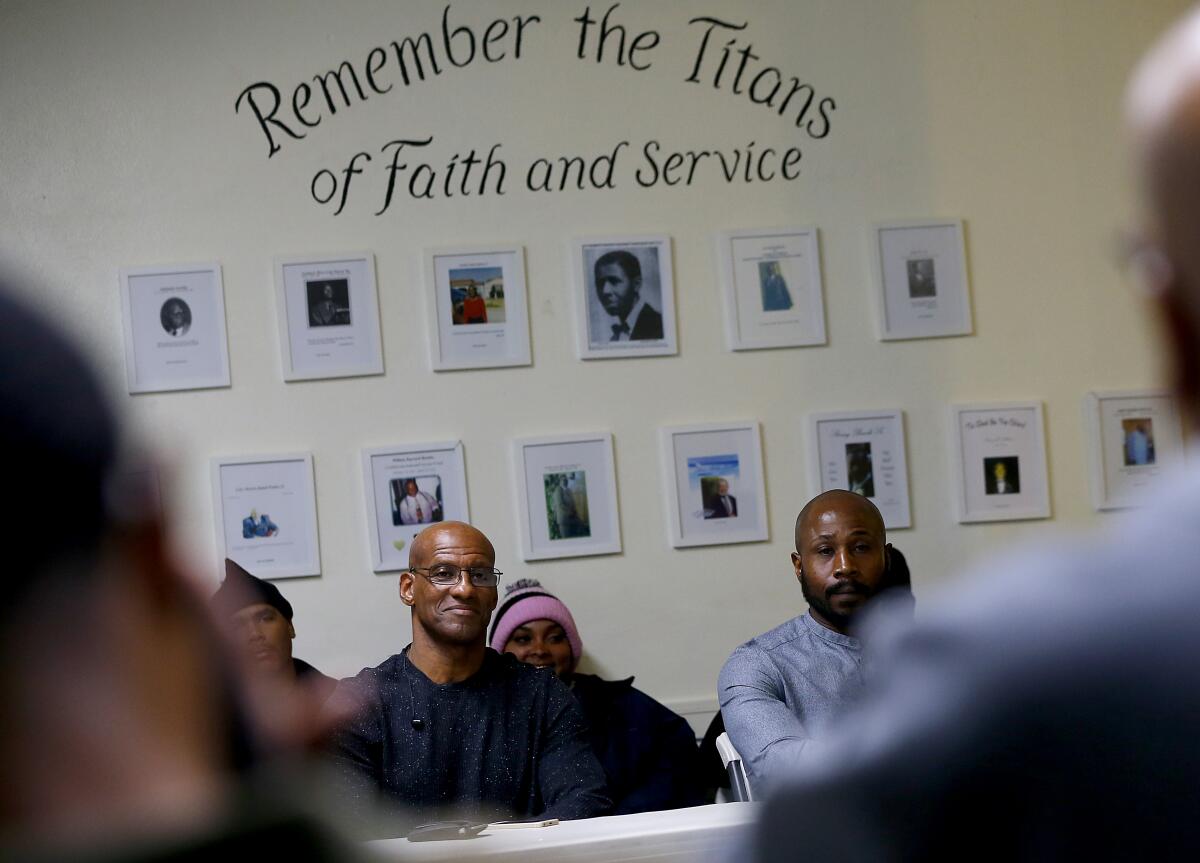

Before the coronavirus outbreak forced the cancellation of gatherings, 2nd Call met every Thursday night in a church basement in South Los Angeles. John “Big John” Harriel Jr. led the meetings to teach other former convicts how to live life outside prison walls.

You can’t hide in the back. You can’t sneak in late. Big John will make you answer.

Your name. How you’re feeling. Where you’ve been. Where you’re headed.

Kyung is one of the first to speak. He is electrified. Everything is going right. He has an important interview tomorrow.

Big John howls in appreciation. Then he asks, “Ever been in that special place?”

“Yes, sir, I have. Altogether, about 10 years.” Kyung’s face is weathered, as if marked by the troubles he has seen.

“Ten years, all right,” Big John says. “And you’re about to become an electrician.”

Until the novel coronavirus hit, anyone who needed a job, some encouragement, or a way to avoid past mistakes, was welcome Thursday nights in this church basement at 35th and Normandie in South Los Angeles, an area plagued by gang violence, a lack of well-paying work, the revolving prison doors.

Many have been to what Big John calls that special place, that gated community. By his calculations, the 50 or so people in the room on this night have collectively logged about 400 years behind bars.

As part of a program called 2nd Call, they learn how to become union electricians or carpenters, how to keep those jobs, how to confront trauma and depression, how to be good fathers and mothers, spouses, sons, daughters and friends.

Big John, whose full name is John Elliott Harriel Jr., taps one person after another, eliciting snapshots of their lives with a quick patter of questions, as he does on this night, before social distancing kicked in.

Exams passed, careers made — it is a mantra of success, relished again and again. If he can do it, so can you.

“How you feel, Sal?” Big John asks.

Sal feels blessed. He will finish electrician boot camp on Sunday.

“OK, how’d you get that?” Big John says.

“Right here at 2nd Call,” Sal responds.

“You ever been to prison?”

“Yes, sir.”

“How much time you do?”

“Just finished doing 14.”

“Man, your life is about to change, buddy.”

::

The gray floor is pockmarked. Fluorescent lights illuminate the faces of the people seated around a large square table, against the walls, in rows stretching to the back, most of them men, most of them African American, some clad in work boots and long-sleeved T-shirts bearing the logos of construction contractors.

As the nickname implies, Big John, 50, fills out his black Local Union 11 sweatshirt, his direct manner more intimidating for his bulk. But he is quick with a joke or sympathetic word to leaven his bluntness.

And he has been there.

“My name is John,” he says. “I feel excellent that I ain’t dead or in jail. Have I been to jail? Yes. But I keep those things behind me. I try to look in that rear-view mirror just for a reference, that’s it, to make sure I don’t put myself in no situations.”

After serving seven years for drug offenses in the 1990s, Big John was determined not to go back. A fellow inmate had taught him basic electrical skills, and he found work in the trade. Eventually, he met Skipp Townsend, who had started 2nd Call with Kenny Smith and was trying to get jobs for gang members.

Big John became a conduit to highly paid union jobs. He knew what kind of work ethic and interpersonal skills it took to thrive in those jobs — hence, the Thursday night meetings, which he has led since 2009, every week except Thanksgiving, in a space lent by a sympathetic pastor. The small stipend 2nd Call could offer pales compared to what Big John makes as a supervisor at the electrical contractor Morrow Meadows, so he accepts no payment.

Townsend, the bald and bespectacled eminence of the Los Angeles gang intervention world, is 2nd Call’s executive director and is usually at Big John’s side on Thursday nights, though he is absent tonight.

Big John has put his own touch on a format pioneered by 2nd Call, drawing on a repertoire of topics key to life and work: forgiveness, leadership, self-esteem, excuses. He quickly schools newcomers in the lingo. Careers, not jobs. Speak only for yourself — no “we’s” or “you’s.” The 2nd Call wolf pack takes care of its own.

Until the pandemic, some people came by every Thursday, week after week, year after year, long after establishing themselves in their careers. Others sought out the meetings when they were in a rut.

For the most part, they introduce themselves using first names only: Sal, Tak, Deontae, Vince. Next is Nikia.

“This program, I’ve been through so many of them, so you know,” Nikia begins.

Big John cuts him off.

“First of all, throw the word ‘program’ out of your vocabulary. It’s not a program. It’s a way of life. Ain’t no beginning, ain’t no end.”

Nikia is back from 22 years in the penitentiary.

“Hoooh-oooh,” Big John marvels. “Welcome home.”

Something troubling happened the night before, Big John says, hinting at a disagreement at a job site involving people from 2nd Call.

He enumerates some pleasures of life on the outside — sleeping on comfortable sheets, soaping up a loofah sponge in the shower. This is what you could lose with one violent outburst.

Anger progresses in four stages, according to a handout: (1) Communication breakdown (2) Mental warning (3) Physical warning (4) Aggression and actions.

Kyung says he used to be “a hell of an angry person” who needed to prove himself by being “the biggest badass.”

“I got appreciation of my life back, the things I truly care for, that I should have cared for,” he says. “My concern right now is the future.”

Charles, now a union electrician after 27 years behind bars, says he has spent years unlearning knee-jerk reactions that were normal where he came from.

“When I was coming up, you say a certain word, or dress a certain way — it was not just getting angry but the response to the anger,” he says.

Big John notes that some familiar faces are gone from the meetings because they let their tempers get the better of them.

“Some people, the reason why they ain’t here no more is they went from zero to 60 in 10 seconds. One of them got double life right now, and one of them got 34 to life. All over zero to 60.”

After 23 years, the humble elotero Andres Santos has hawked his final kernel. He headed home to Mexico to chase that grandest dream of all: love.

According to Big John, the man who lashed out angrily in last night’s workplace incident will probably face criminal charges and lose his $50-an-hour foreman job.

“His flow’s about to stop. And he probably has a family. So he had a communication breakdown, and he went to No. 4,” Big John says, referring to the highest stage of anger. “Now he’s about to be unemployed.”

Monica, a union electrician, says her co-workers often treat her unfairly because she is a black woman. She talks back but knows she is walking a fine line.

“If they say something to me, I’ll say, ‘I don’t like the way you said that. You didn’t say that to him.’ I’ll let you know I’m not with that,” she says. “But I have to really, really be careful. The first thing they want to do is get you off the job. Any opportunity, they want you gone.”

::

Big John goes around the room, asking each person: “Anything we spoke about tonight stood out to you?”

The transition from prison can be overwhelming, and discussions like this one keep him grounded, Sal says.

“Coming from the four walls, being trapped, then coming out here to the real world, it’s so easy to get tripped up over some little small stuff,” he says. “Let that go — I got so much ahead of me right now.”

When Sal was insulted by a co-worker recently, he called Big John.

“I said, ‘Yo, this is how we’re going to do this. Do not do nothing to that guy. Let’s walk away,’” Big John recalls. “Now, by him not doing what he was going to do three months ago, he has an opportunity to change his life.”

A young man arrested in a terrorism plot inspired by Islamic State visited his former jailers to thank them for steering him down a better path.

Vince, who is wearing a Morrow Meadows T-shirt and is switching from the carpentry to electrical trade, says thinking back on his prison days helps him appreciate where he is now.

“Not that you’d want to go to that special place. But I know people learn from that, too,” he says. “I know for me, it helps me get a whole different perspective on life.”

A man with his hair in two braids says it’s hard to undo old habits and walk away from a conflict.

“And so for me to overcome that, listening to all you guys, it’s helping me out right now,” he says. “So now that seed has been fed, and it’s being watered.”

Mark, who spent 40 years in prison, says controlling your feelings is “mandatory.”

“If I’d have learned that 30 years ago, I would have been out 30 years ago,” he says.

Big John closes with another reference to the four stages of anger.

“I always remind myself, if I stay at 1 and 2, I can stay out of jail and I won’t be dead.”

In weeks to come, the coronavirus would put the Thursday night meetings on hold. Big John does not know how to use Zoom. Even if he did, much would be lost in a virtual space.

But on this night, the men and women here find the fellowship they need. As they do every week, they give thanks. Chairs slide. They stand in a circle, linking hands. A man named Lee says a prayer.

“Dear Father, thank you for 2nd Call, thank you for Thursday, thank you for this meeting, for this church. Bless our families, bless us individually, help us keep our minds and stay on you, in the right place. In the name of Jesus we pray, amen.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.