Saturn 500F rocket from the Vehicle Assembly Building in Florida. Developments in the 500F help pave the way to the Saturn V.

In early days of America’s space program, two men met over a bottle of Jack Daniel’s at the Hay-Adams hotel across the street from the White House.

It was roughly 1959, when the future of America’s young space program was clouded by technological disagreements.

On one side of the bottle was Wernher von Braun, the engineering genius who had developed the world’s first ballistic missile for Adolf Hitler during World War II. He had once been a member of Hitler’s Schutzstaffel, or SS, but now ran NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala.

On the other side was Abraham Silverstein, who had grown up in a poor Jewish family in Indiana. He was NASA’s space flight chief and later became director at NASA’s Lewis Research Center in Cleveland.

One former Nazi, one American Jew. Little more than a decade separated them from the Holocaust.

Looming before two of America’s top rocket engineers were many critical decisions, including what kind of fuel would be needed to blast off astronauts to the moon.

Von Braun wanted the second and third stages of the mighty Saturn V rocket to be powered by kerosene, a fuel he understood from his days in Germany. There, he led development of the alcohol-fueled V-2 missile that bombed London.

Silverstein had guided research at Lewis in liquid hydrogen, a much more powerful fuel that had never been used in a rocket before. He was certain such a technological leap was necessary for the long lunar journey.

An observer later recalled the men sizing each other up like “spiders.” Two of the nation’s most important rocket experts were locked in a technical dispute of enormous importance that revolved around a cautious versus bold engineering approach to future space travel. Their vast personal differences were swept aside.

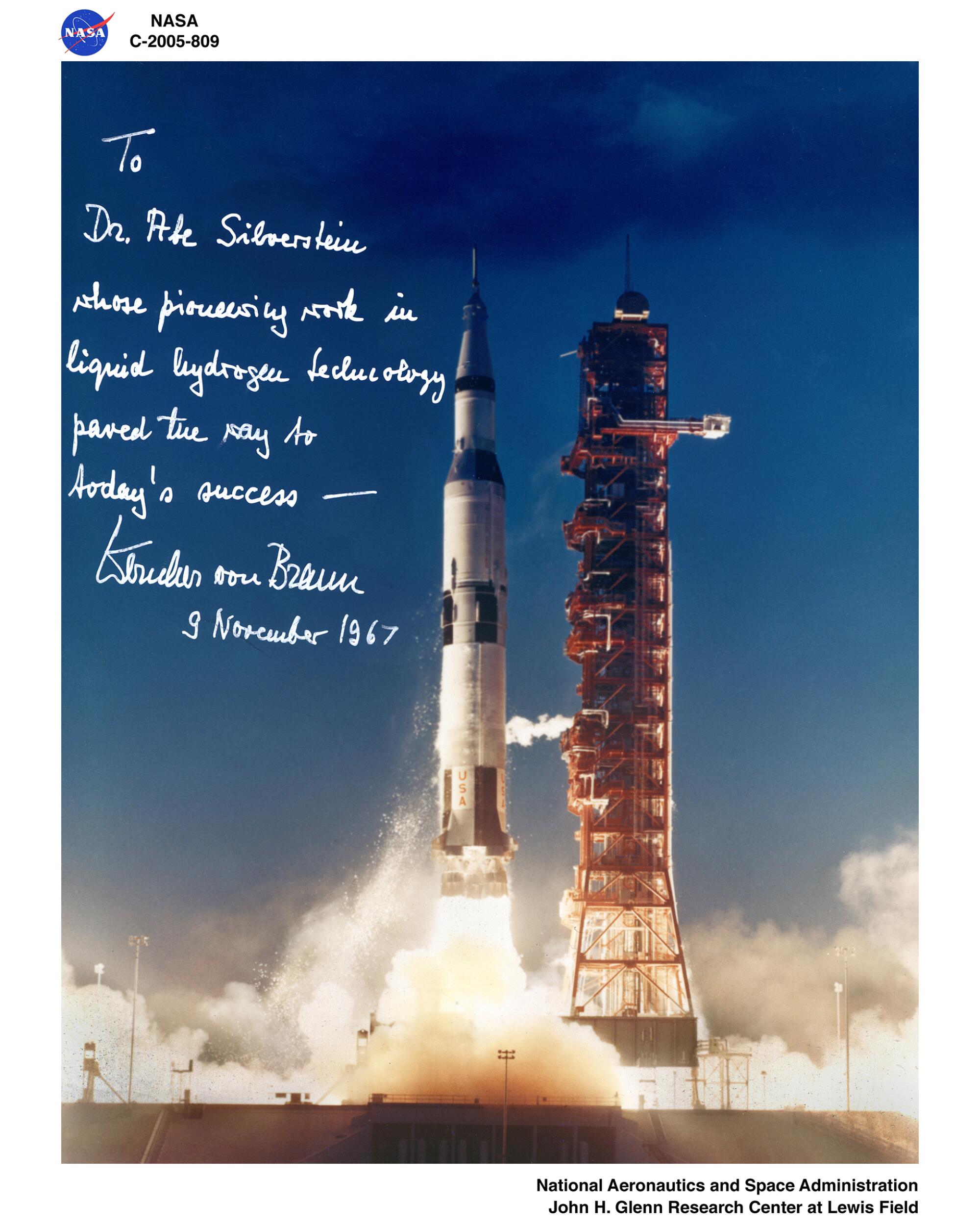

When the first Saturn with hydrogen-powered stages was tested on Nov. 9, 1967, Von Braun sent a photograph of the launch with a handwritten note: “To Dr. Abe Silverstein whose pioneering work in liquid hydrogen technology paved the way to today’s success — Wernher von Braun.”

The collaboration between Von Braun and Silverstein was not unique. During the Apollo program, which landed Americans on the moon six times between 1969 and 1972, NASA was filled with both Jewish scientists and a large group of Germans who had worked for Hitler before and during World War II. The Nazi regime had been dedicated to the extermination of Jews. That the two groups were able to work side by side suggests a level of reconciliation, or at least acceptance, that would seem a near impossibility in today’s fractious social and political climate.

Apollo-era engineers, space historians, the engineers’ children, religious leaders and political analysts say the quiet collaboration was based on intellectual respect, a belief in redemption and a partnership forged for the nation’s benefit.

It was an era when moral judgments took a back seat to a deeply held commitment to the future of space travel and support of national goals.

The children of both the Germans and the Jews say there was never any talk at home about resentments or bigotry. Instead, their parents were laser-focused on the monumental challenge of the lunar mission. NASA historical records tell the same story.

It helped to have a little humor too.

“My dad said NASA was built by Jews, Nazis and hillbillies,” recalled Reuben Slone, the son of NASA engineer Henry Slone, a member of the Cleveland Jewish community.

The story of that collaboration has scarcely, if at all, been written about, space historians say, though much has been written about the German scientists and some about various Jewish scientists.

In recent years, a deeper analysis has focused on America’s decision to bring 125 German rocket scientists and engineers to the U.S. after World War II under a secret program approved by President Truman and code-named Operation Paperclip.

Historians have delved into the extent to which German rocketeers were complicit in atrocious conditions at an underground factory near Nordhausen that produced the V-2, the world’s first long-range, guided ballistic missile.

It was staffed by prisoners from the nearby Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp, which held French and Belgian Resistance fighters, along with Russians, Poles and other Slavs, according to Smithsonian senior curator Michael Neufeld, a leading author on the German scientists.

The factory was controlled by the Nazi armaments ministry and the SS paramilitary organization, Neufeld said, but a number of the V-2 engineers at least witnessed the inhumanity that led to the deaths of an estimated 20,000 prisoners.

Knowledge of those conditions, absent involvement, would not constitute war crimes, said Eli Rosenbaum, the Justice Department’s longtime Nazi hunter. But in some cases, U.S. military authorities did a poor job of investigating the German scientists, he said.

Much of the history of the underground factory was held secret from the American public until the 1970s. The U.S. Army decided it was critical to national security to quietly recruit the German scientists, based on fear that Soviet leader Josef Stalin would develop long-range missiles with atomic warheads first and use them preemptively against the West. One thing also united many of the NASA Jews and Germans: a mutual hatred of communism.

There is wide agreement that the collaboration between Germans and Jews was essential to the Apollo moon landings and much of the U.S. nuclear deterrent.

“It is 100% true,” said Brian Odom, the historian at Marshall Space Flight Center.

Such a collaboration without public furor “would be impossible today,” said Charles Bolden, a former NASA administrator, astronaut and Marine Corps major general.

Bolden said he can relate to how the Jews felt. He recalled a time when NASA asked him to command the first joint space shuttle mission in 1994 with Russian cosmonauts in the aftermath of the Cold War.

“I said, ‘I’m not flying with any damn Russians,’” Bolden recalled. “‘I am a Marine and I trained all my life to kill them, and they have done the same.’”

But he relented when he met his Russian partner, and they became lifelong friends. Still, Bolden, an African American from South Carolina, was asked: Could he have made a similar leap to work with a former member of the Ku Klux Klan?

After a long pause, he said, “My hope would be that I would be big enough to see what kind of a person they are now, and let’s see if we can establish some kind of commonality between us. That might make a difference.

“I am certain that is what happened with Abe Silverstein and the [other] Jewish guys,” Bolden added. “We are putting what is good for the country ahead of anything personal. I am almost certain we wouldn’t see that today.”

The Times reviewed hundreds of pages of NASA’s Apollo documents, dozens of oral histories by Germans and Jews, and interviewed the children of the engineers to understand how these two groups interacted in one of the greatest technical achievements in history.

To be sure, some believe Operation Paperclip was morally tainted.

“How could it possibly be that these people, who used slave labor, came here?” asked Rabbi Abraham Cooper, director of social action at the Simon Wiesenthal Center. “It is a realpolitik thing. If we didn’t grab them, the other side would. But there is a price to pay to humanity when you make those kinds of decisions. As a Jew, I do have misgivings.”

Rosenbaum, who ran the Justice Department’s Office of Special Investigations that prosecuted war crimes, takes a similar stand: “All of them had some responsibility for this abuse of concentration camp inmates and the forced labor used in the factory.”

Many space technologists want no part of rethinking the Apollo program, arguing that it was a different era and that the Germans became exemplary Americans.

“Not to have brought them over would have been a crime,” said Daniel Goldin, a Jewish engineer from New York who became the longest-serving administrator in NASA history. “You could get dogmatic about it, but the Cold War could have ended the world.”

On a personal level, Goldin struggled in his first encounters with the Germans.

He joined the NASA center in Cleveland under Silverstein and became an early advocate of electric-powered rocket engines. In 1963, he met the world’s foremost expert in the field, German rocketeer Ernst Stuhlinger.

“I had to fight my instincts,” he said. “This was the first German I talked to. Here was the father of electric propulsion, and I was just a kid. The night before I was quite nervous.”

After meeting Stuhlinger, he recalled him as “a very gentle, smart man.”

The interactions between Von Braun and Silverstein were at a much higher level and the best documented in the historical record, but similar relationships were typical throughout the NASA ranks.

“Dad was part of the World War II generation who felt that it was for the greater good of the country,” said Reuben Slone, who became an engineer after his father, Henry, persuaded him to avoid law school. “He made light of it. I am sure he was uncomfortable with it, but my dad saw it as a patriotic duty.”

The Germans had been brought in waves in the mid-to-late 1940s to work in the Army’s ballistic missile agency at Ft. Bliss, a desolate patch of Texas desert, and then to the Army’s Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, where they helped pioneer America’s early ballistic missiles, including the Redstone and Jupiter. They transferred to NASA when it was created in 1958.

Huntsville was a poor, segregated city with a single liquor store that had one door for white patrons and another for black patrons, recalled Sherman Mullin, who worked in Huntsville in the late 1950s and later became chief of the top secret Lockheed Martin Skunk Works in Southern California.

“There were basically four groups in Huntsville — the local whites, the blacks, the Germans, and everybody from out of town, who were considered Yankees,” Mullin said. A white man from Southern California, he fell into the last group. “None of the groups mingled. A Yankee couldn’t get a date with a young lady in that town.”

The Germans settled together in a neighborhood that locals harshly dubbed “Kraut Hill,” according to Odom, the Marshall historian. Many of them were cultured in classical music and literature, some had nobility in their backgrounds, and quite a few had doctorates from the best universities in Europe.

The German families forged their own close community, founding a Lutheran church, building furniture in their home woodworking shops and celebrating holidays together. By all accounts, they worked hard to assimilate, gaining citizenship, sponsoring the creation of a Huntsville symphony and pushing successfully for a University of Alabama engineering campus in Huntsville. Von Braun ordered his men, despite their poor English, never to speak German when others were around.

“They were so grateful to have the opportunity to come to this country,” said Heidi Weber Collier, daughter of guidance and control engineer Fritz Weber and the unofficial archivist of the Germans.

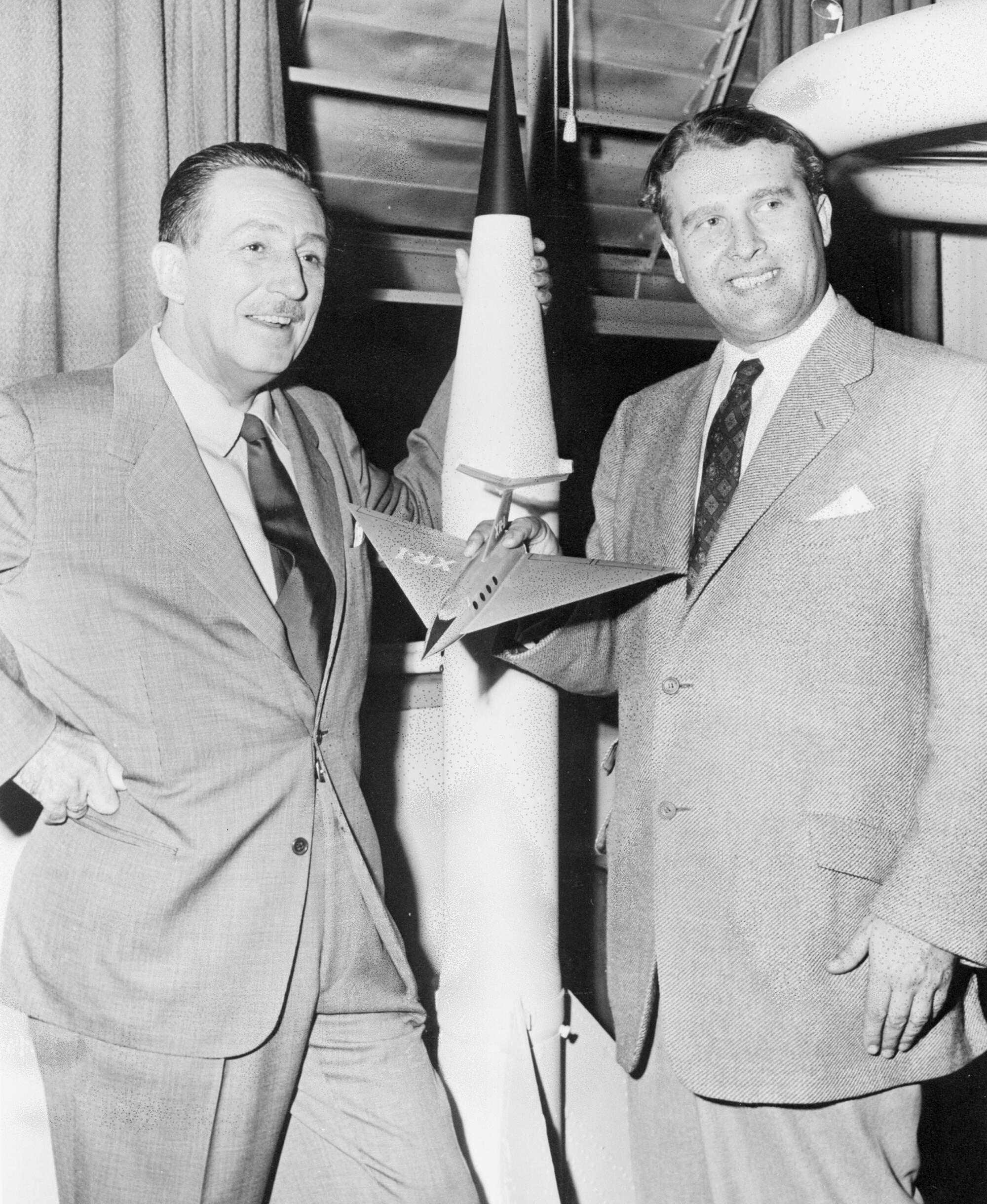

By the late 1950s, Von Braun had become an American sensation, appearing on major magazine covers and featured on Disney television shows as a futurist space wizard. He became one of the leading voices fueling public enthusiasm for space. His Nazi background was rarely, if ever, mentioned.

Like many of the German scientists, he maintained a formality that was sometimes out of sync with American culture.

Slone, the Jewish engineer in Cleveland, told his son Reuben that when Von Braun walked into the room, all the junior engineers had to stand at attention.

To the Germans, titles were important.

At a cocktail party in 1960, an astounded American engineer asked Von Braun’s right-hand man, Eberhard Rees, “Do you mean that you’ve been working together for, whatever it is, 20 years, and you’ve been calling him Dr. Von Braun all this time?”

“Oh, no!” Rees answered. “I always called him Herr Doktor Von Braun.”

Von Braun is certainly the best known of the German scientists, but they filled almost every key department at the Marshall Space Flight Center.

Kurt Debus ran the launch site that would later be renamed the Kennedy Space Center. Rees was Von Braun’s technical director and succeeded him as Marshall chief. Arthur Rudolph was chief of the Saturn V rocket development. Werner Karl Dahm became one of NASA’s chief aerodynamicists. Konrad Dannenberg was deputy manager of the Saturn.

“Boy, were they good engineers,” said Gerald Griffin, an Apollo flight director and aeronautical engineer, who later became chief of the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

On the Jewish side, Silverstein helped set up the entire human space flight program before NASA was created in 1958. Abraham Hyatt, who fled Ukraine with his family before World War II, was a headquarters planning director. Milton Rosen was chief of NASA’s science mission directorate. George Low became deputy chief of NASA, known for his advocacy of the gutsy 1968 decision to orbit the moon after only one human test flight of the Apollo system. Louis Rosenblum was a key technologist in energy. Slone specialized in propulsion. Erwin Zaretsky was one of the world’s top experts in ball bearings and machinery lubrication.

Among the few engineers from that era still alive, Zaretsky can’t recall the issue of the Germans’ background being discussed among Jews. “It was immaterial,” he said.

Von Braun and Silverstein could not have been more different, although both had a commanding presence and were always impeccably dressed.

Von Braun was a Prussian aristocrat, the son of a baron. He attended top technical schools in prewar Germany. Though he was a dynamic leader, his approach to engineering was cautious and conservative.

Von Braun was both a member of the Nazi Party and an officer in Hitler’s elite, and murderous, SS security organization, a position he probably could not turn down without losing his job as chief of the German army’s missile research.

Neufeld calls it Von Braun’s “streak of amoral opportunism.” America’s technology industry today has come under similar criticism for its ties to oppressive foreign governments. Von Braun’s death in 1977 preceded the Justice Department’s deeper investigations of the Germans.

Silverstein, whose parents emigrated from Eastern Europe, grew up in a large family in Terre Haute, Ind., and attended a small but well-regarded private engineering school there.

He was low-profile, but liked working in the technical trenches and brought an ambitious agenda to NASA — pushing for a revolutionary type of rocket engine and conducting the research to achieve it at the center in Cleveland. It was Silverstein who chose the moon program’s name of Apollo, for the Greek god of light, music and the sun.

The meeting at the Hay-Adams hotel between Von Braun and Silverstein was recalled in a 153-page recorded conversation with Silverstein taken in 1974 after he had left NASA. The interview was conducted by John Sloop, who had been at the hotel room meeting as a member of Silverstein’s technical staff.

Sloop recalled the probing interactions of the two technical titans. “To me, that was a beautiful example of each feeling out the other almost like spiders, like a couple of spiders,” he said.

Sloop, perhaps because he had worked so closely with Silverstein, raised “the recurring question of animosity between you and Wernher.”

“There was no animosity,” Silverstein replied.

“And you could understand this because of your Jewish heritage and his Nazi support,” Sloop countered.

“But that was not — that was never,” Silverstein cut him off.

“It wouldn’t be unnatural for you to have animosity,” Sloop pushed back.

“It would be, because I don’t do that, mostly,” Silverstein said.

In fact, Silverstein said he was in favor of bringing the Germans into the NASA fold, because “they were an important cog in the business and to have left them out would have been silly.”

The recorded exchange is perhaps the only one in which a Jewish engineer directly addressed his relationship with the Germans.

The children of several of the Jewish engineers say their fathers never spoke to them about hatred or anger, though they suspect they were uncomfortable.

“He didn’t talk directly about it,” said Judy Cook, Silverstein’s daughter. “When the subject came up, you could tell he was not fond of them.

“I came home one day and told him somebody at school said Wernher von Braun is head of NASA. He seemed a little bit angry and said, ‘He certainly is not.’ But he was very, very practical and cared that the space program would succeed.”

David Silverstein, a son and an aerospace engineer, said, “I am sure he was not totally fond of the situation, but he focused on the task at hand. He was subdued about his feelings unless it involved his family.”

Although he was not known as deeply spiritual, Silverstein was a committed Jew. One day, he called all the Jews at the Lewis Research Center into his office and proclaimed that they would be founding members of a new synagogue called Beth Israel-The West Temple. It still serves the west Cleveland community.

Asked how the Jewish scientists could work with the Germans, the synagogue’s leader, Rabbi Enid Lader, said: “It shows the potential for forgiveness. These engineers were driven by a very sincere Jewish value to work for the good of society. For the German scientists, this gave them the opportunity to turn their work used for evil to good. It is redemption.”

Moreover, the Jews had to deal with plenty of discrimination in America. Many went to work at NASA specifically because they were blocked from jobs in private industry.

By no means were Silverstein and the other Jews afraid to stand up for their beliefs. By the 1960s, they founded the Cleveland Council on Soviet Anti-Semitism, aiming to expose the persecution of Soviet Jews.

Rosenblum, one of the key founders of the council, became very active, and his daughter Miriam was arrested in the Soviet Union for meeting with Jewish dissidents just after the 1974 summit between President Nixon and Soviet leaders, she recalled.

The children of the German engineers say their fathers have been unfairly judged.

Their image took a beating when Rudolph, who ran the very Saturn rocket development that boosted the astronauts to the moon, came under investigation by Nazi hunter Rosenbaum at the Justice Department.

Rudolph had overseen production at the Nordhausen factory. Allegations were later raised that he had advocated for using concentration camp labor. He also was accused of disguising his enthusiasm for the Nazi Party during Army investigations of his background. He was stripped of his U.S. citizenship in 1984 and sent back to Germany, although authorities there never prosecuted him. He died in 1996.

Many of the Germans thought it was wrong to condemn Rudolph after he had contributed so much to the Apollo success. The children bristle when their fathers are called Nazis.

“People would ask about my family history and they would say, ‘Oh, my God, your father was a Nazi,’” said Weber Collier, daughter of Fritz Weber.

Margrit von Braun, the rocket master’s daughter, said she chooses to hold on to her own memories of her father and avoids reading books that cast him in a harsh light.

Von Braun, a retired engineering professor at the University of Idaho who now does international humanitarian work, said she doubts he had any discomfort working with Jews.

Her father, an accomplished classical pianist, once played music with Albert Einstein, the Jewish scientific genius who fled Germany before the war, she said.

“My parents, as much as they could, were very passionate about the civil rights movement,” she said. Her father “really didn’t talk about the war. It was pretty common for that generation to put the war behind them. They volunteered to come to America.”

She still recalls with pride when, as a teenager, she watched her father hoisted onto the shoulders of Huntsville city leaders after the first Apollo moon landing and carried to the town square, where he gave a speech.

Magnus von Braun, Wernher’s younger brother and another key rocket engineer, also surrendered to American forces in May 1945. After working for the Army for a decade, he took a job in Detroit at Chrysler Corp., which was building America’s first generation of rockets that the Germans in Huntsville were designing.

It was a job not unlike the one he had in wartime Germany, when he worked under Rudolph overseeing V-2 production. That put him closer to the abusive use of slave labor than his older brother.

“He felt nauseated, but he couldn’t back down or he would have been shot,” said his son, Curt von Braun, who obtained a doctorate in aerospace engineering and works at a major U.S. defense firm. Unlike many of the other German children, he probed his father for information about Mittelbau-Dora.

“It was too much trauma. He said he witnessed hangings. He said Germany was in his past. Even if you were a member of the Nazi Party, it doesn’t make you a racist. Not everybody believed all that crap,” Curt von Braun said. “These [engineers] were good people.”

The German engineers not only helped land Americans on the moon, but played a key role across the nation’s defense programs, and there too they collaborated with American Jews.

Adolf Thiel was recruited to aerospace giant TRW’s Space Park in Redondo Beach by its chief, Simon Ramo, one of the most important Jews in American aerospace.

Thiel, a former Nazi Party member, rose up to run all of TRW’s spacecraft operations, putting him in charge of the nation’s most sensitive intelligence and defense satellite programs. During Apollo, TRW developed a revolutionary rocket engine with variable thrust that was critical to the lunar module’s landing.

Thiel and Ramo became friends, recalled Thiel’s son, Michael.

“I remember Ramo coming to our house for dinner in Palos Verdes,” said Thiel, who was born in Huntsville.

Ramo was an accomplished violinist. Adolf Thiel’s wife was a trained classical pianist. After dinner, they played a duet in the living room, he said.

On the 50th anniversary of the first moon landing in July, a few dozen children of the German engineers returned to Huntsville for a reunion, joined by former astronauts and American aerospace industry officials, Weber Collier recalled.

Griffin, the flight director on the Apollo mission and later chief of the Johnson Space Center, doesn’t like the idea that anybody would second-guess the American success in space.

“Everybody was pulling on the same oar, making sure we would succeed,” he said.

“You would think there had to be some hostility, but I never saw any. ... People are willing to change. There is no redemption in today’s society.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.