Their kids died on the psych ward. They were far from alone, a Times investigation found

Mia St. John’s cellphone lit up with a message from the psychiatrist treating her son. The voicemail shimmered with hope, the first she had felt in months.

The doctor said Julian, admitted to a psychiatric facility with schizophrenia, seemed more cheerful, was talking more with other patients and would soon begin a new art project.

“Very happy to see he’s coming around a bit,” the doctor said.

It was November 2014, and Julian, 24, had been living at La Casa Mental Health Rehabilitation Center in Long Beach for two months. Mia and her ex-husband, Kristoff St. John, had resorted to involuntarily committing their son after he threatened to kill himself in September.

But three days after Mia received the physician’s voicemail, she got another call from La Casa. This time the message offered only despair.

Julian had suffocated himself with a plastic bag. Her son was dead.

How many others die in California psychiatric facilities has been a difficult question to answer. No single agency keeps tabs on the number of deaths at psychiatric facilities in California, or elsewhere in the nation.

In an effort to assess the scope of the problem, The Times submitted more than 100 public record requests to nearly 50 county and state agencies to obtain death certificates, coroner’s reports and hospital inspection records with information about these deaths.

The Times review identified nearly 100 preventable deaths over the last decade at California psychiatric facilities. It marks the first public count of deaths at California’s mental health facilities and highlights breakdowns in care at these hospitals as well as the struggles of regulators to reduce the number of deaths.

The total includes deaths for which state investigators determined that hospital negligence or malpractice was responsible, as well as all suicides and homicides, which experts say should not occur among patients on a psychiatric ward. It does not include people who died of natural causes or other health problems while admitted for a psychiatric illness.

‘The guilt just weighed on him very heavily. I think he felt like he failed his only son.’

— Mia St. John, on her late husband

Like mental illness itself, these tragedies cut across age groups, races and social classes. Among those who died in California’s psychiatric wards were a 15-year-old high schooler in marching band, a 27-year-old who spent his free time volunteering at church and a PhD student in criminology. Julian was the child of a celebrity couple: Mia is a champion boxer and Kristoff starred for more than two decades on the soap opera “The Young and the Restless.”

Although the number of inpatient deaths in California does not appear to be higher than national averages, the deaths reveal serious lapses in patient safety, experts say.

Mental health experts say that while there are rare cases in which a hospital staff cannot prevent the death of a patient on the psychiatric ward, most people admitted can be kept safe. State officials who investigated these deaths largely attributed them to low staffing levels, staff errors, lack of training, or facilities that were deemed unsafe.

At Aurora Las Encinas Mental Health Hospital in Pasadena, a patient died in 2018 after five staff members restrained him on the ground and he stopped breathing. State investigators determined that the staff had not been properly trained in how to restrain patients, records show.

In 2012, a staff member at Kaiser Permanente Mental Health Center in Los Angeles did not check on a suicidal patient every 15 minutes as required, allowing the patient to fatally hang himself in his room, according to a state investigation.

Experts say these problems persist, in part, because of cost. Hospitals would have to spend heavily to improve safety, both to hire more staff and retrofit rooms so they are less dangerous for suicidal patients.

Julian’s death was not the first at La Casa. Two years prior, a 22-year-old hanged himself in his room and died, according to coroner’s records. A state investigation found several errors by hospital staff that led to the man’s suicide, but officials imposed no punishment.

Following almost every death at a psychiatric facility in California, the facility continues operating and does not face a financial penalty. Meanwhile, families remain unaware of the hospitals’ track records.

“Welcome to the black hole,” said Benjamin Miller, a psychologist who is chief strategy officer for the Well Being Trust, a nonprofit dedicated to improving the mental health system. “Everyone should be informed as to what type of care they receive, but that’s the problem with mental health — nobody really knows.”

In the years since Julian died, Mia has become dedicated to fixing the mental health system that she believes killed her son. Kristoff tried to soothe his grief with alcohol and began drinking excessively after his son’s death, Mia said.

“The guilt just weighed on him very heavily,” Mia said. “I think he felt like he failed his only son.”

In February, Kristoff, 52, was found dead in his apartment. Tests showed that he had been severely intoxicated before he died. Mia believes he drank himself to death.

::

In a grainy home video, a young Julian gazes up at Mia as she points to the glowing candles on his birthday cake. In another, a gangly boy shoots hoops with his dad, smiling sheepishly as he sends the basketball into the net. Kristoff ruffles Julian’s hair.

Born in 1989, Julian grew up in Calabasas. His sister Paris was born three years later.

From a young age, Julian showed signs of mental illness, his mother said. He was pulled out of kindergarten for being disruptive. Doctors said he had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder.

He dropped out of high school and was diagnosed with schizophrenia at age 18. He wandered the streets and smoked methamphetamine and other drugs, his mother said.

Mia kept a tracking device in his cellphone, but his phone battery often died when he was homeless. Mia would frantically search for him around Los Angeles. Through a combination of persistence and intuition, she usually found him, often sleeping in parks.

“He could be in his worst psychotic state and he always knew I was mom,” she said.

Julian painted when he was homeless, sometimes using wood and other found objects as his canvas. Along with blankets and food, Mia frequently brought him art supplies.

In early 2013, Julian had dedicated himself to consistently taking his medications and was living with his girlfriend in an apartment. A gallery in Laguna Beach displayed his art, which featured numerous self-portraits.

But 18 months later, in September 2014, Julian hit a low point. He called his mother from a pay phone and said he was planning to kill himself.

Upon his admission to La Casa, staff members deemed Julian a severe suicide risk and were supposed to check on him every 15 minutes, according to a legal complaint filed by the St. Johns.

But over the next few weeks, Julian was found smoking and having empty vodka bottles in his room, according to the court complaint. Once, he escaped from the facility, the St. Johns alleged.

Mia and Kristoff worried but felt they should be grateful just to find their child a bed in a psychiatric facility.

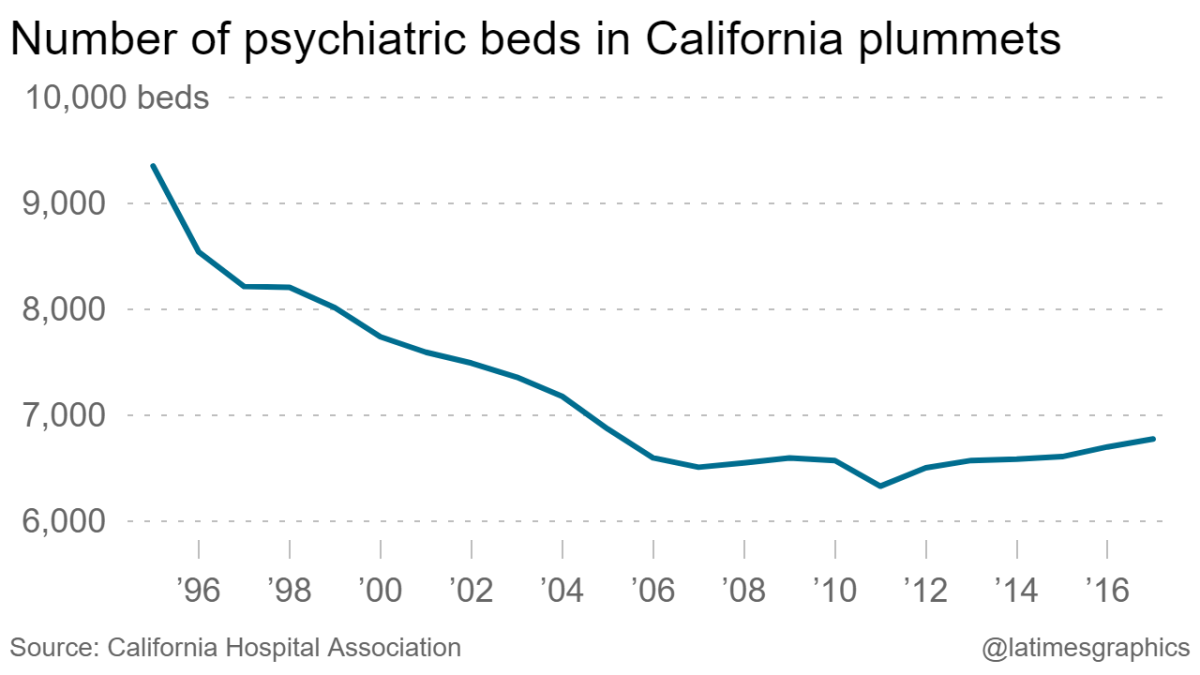

California needs 50 psychiatric hospital beds per 100,000 people, yet it has only 17, according to a 2018 report from the California Hospital Assn. Patients in the midst of a psychiatric crisis can wait in the emergency room as long as a week for an available bed.

“The problem is that a lot of times people don’t have any choice,” said Ann Coller, who worked in patient rights advocacy in California for 28 years.

La Casa is not designated as a hospital but as a mental health facility that can accept patients who are placed on an involuntary hold. In California, there are more than 30 such facilities, in addition to 120 hospitals that have psychiatric beds. The non-hospitals are often presented as better options for patients like Julian who need longer-term care.

The St. Johns had no way of knowing that two years earlier, Travis Kelly, 22, had died by suicide at La Casa. Or that facility staff had not properly monitored Kelly given his high risk of suicide, including a recent attempt in the facility, according to an investigation by the state Department of Mental Health that identified several problems with La Casa’s care.

The Kelly family sued La Casa’s parent company, Telecare, and settled in October 2014, while Julian was staying at La Casa.

But state investigations into problems at psychiatric hospitals often are not released by the state. There is no centralized public database of patient deaths or a safety rating system that families can rely on when choosing a facility, unlike non-psychiatric hospitals.

Mental health advocates also say there has been a drop in oversight since the state Department of Mental Health was dissolved in 2012 and its duties were distributed among several agencies.

On Nov. 23, three days after Mia received the voicemail from Julian’s physician saying his condition was improving, Mia called Julian at La Casa to check on him. He told her that he was hearing voices.

She tried to talk him down: “You trust me, you know they’re not real,” she recalled telling him. “I thought I’d convinced him.”

An hour later, the staff found Julian face-down with a plastic bag over his head. He was pronounced dead.

The St. Johns sued Telecare and settled with the company in 2017. The terms of the settlement prevent the family from speaking in detail about Julian’s time at La Casa.

But court documents filed by the St. Johns claim that Julian had tried to take his life three weeks before in the exact same manner, “in the exact same place, and using the exact same type of plastic bag.” After the suicide attempt, the staff did not take the plastic bags out of the trash cans in Julian’s room or elsewhere on the floor, according to the St. Johns’ complaint.

“Julian’s chance to recover from his illness and lead a rewarding life was taken away by the widespread and pervasive negligence” of Telecare and La Casa, the complaint said.

Telecare officials said they could not comment due to patient privacy laws. But they said they closely follow best practices around suicide prevention and would support proposals to increase transparency at their facilities.

“While there have been no recurrences at La Casa since 2014, any suicide is unacceptable. We recognize the imperative of persistent vigilance to keep all persons safe while in our care,” officials said in a statement.

Since 2009, more than 50 people have killed themselves while admitted to psychiatric facilities in California, and an additional 30 have attempted suicide but survived, according to documents reviewed by The Times.

Though suicide is often represented in popular culture as a persistent death wish, it tends to be impulsive — a desire that comes on quickly and can pass just as quickly, said Johns Hopkins University psychiatry professor Dr. Paul Nestadt. That can make the psychiatric hospital vital to a patient’s long-term safety, he said.

“If you can just hold someone long enough to keep them safe, for a couple of days even, you have a good chance of having that impulse pass,” Nestadt said.

More From This Series

But patients aren’t always kept safe. In 2006, the U.S. Department of Justice stripped California of control of four state-run mental hospitals for failing to prevent suicides and assaults and provide appropriate care to patients. The state invested millions of dollars to improve patient safety and was released from the oversight in 2012.

The Times analysis shows that the problems federal monitors had outlined at those state-run facilities continue at other public and private hospitals across the state.

The data collected revealed not only deaths but also hundreds of physical and sexual assaults against patients over the last decade, including two staff members who broke a patient’s arm, a staff member who raped an 18-year-old patient reading in her room and a nurse who restrained a pregnant patient by sitting on her belly, potentially injuring her or her unborn child.

Advocates say a lack of transparency in the mental health system can permit such problems to continue.

Nationwide, there is almost no publicly available information on psychiatric hospitals, such as patient outcomes or patient-to-staff ratios. It wasn’t until last year that a data-based estimate of the number of people who die while admitted to psychiatric hospitals in the U.S was released: 49 to 65 people annually.

“In 2019, when you can’t find an easy answer to questions that actually should be totally answerable, what does that say about the state of our mental health system?” said Miller with Well Being Trust. “To me, it feels like discrimination.”

Since Julian’s death, Mia has lobbied local and state health departments to publicize facilities’ track records. She envisions a grading system that would show an A, B or C for a psychiatric facility, reflecting how many people have died there.

“Wouldn’t you want to know before you sent your child there?” she asked.

But the state mental health law — the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act — includes a strict confidentiality provision. State officials say the law prevents them from releasing reports on errors at psychiatric hospitals that are regularly released for other hospitals.

The extra privacy provisions are probably intended to encourage people to seek mental health treatment by assuring them their identities will remain private, said Pamila Lew, an attorney with the nonprofit Disability Rights California.

“The irony is when this confidentiality protection is used by providers to hide their negligence,” Lew said.

In 2013, Jessica Grebenkemper hanged herself at UC Irvine’s psychiatric hospital. The 26-year-old’s pursuit of a doctorate in criminology at the university was often thwarted by severe mood swings that came with her borderline personality disorder.

A state investigation into Grebenkemper’s death found the hospital staff members had assessed her improperly and had not checked on her every 15 minutes as they were supposed to, “resulting in (her) suicide and death,” according to the state report.

Her mother, Mary Grebenkemper, who lives in Saratoga, Calif., mourns the loss of her only daughter, the girl with the bright smile, the life of the party, who graduated from college summa cum laude.

“They told us she would be safe,” said Grebenkemper, 72.

The state is required to investigate deaths and other problems at hospitals and has the power to financially penalize facilities that have seriously endangered the safety of patients. Despite hundreds of patient deaths and assaults at psychiatric hospitals since 2009, California has imposed just 35 financial penalties — ranging from $30,000 to $100,000 — against these hospitals in that time period.

UC Irvine was fined $75,000 following Grebenkemper’s death.

Last year, a psychiatric patient admitted to UC Irvine’s emergency department wrapped a cord around her neck in a suicide attempt. The hospital failed to put her in a room that was safe for suicidal patients, and the staff member assigned to continuously monitor her was assigned to watch multiple people, a state investigation found. Experts say continuous monitoring generally means that a staff member is exclusively assigned to watch a single patient at all times to prevent self-harm.

UC Irvine officials said they could not comment due to patient privacy laws but said the health system “has taken significant steps in recent years to ensure that patient safety protocols meet our community’s increasing need for behavior health services.”

“UCI Health continuously seeks ways to improve the care it provides to our patients,” officials said in a statement.

Over the last decade, there has been little progress nationwide in bringing down hospital suicide rates, said Dr. David Baker, executive vice president for healthcare quality evaluation for the Joint Commission, which accredits the vast majority of the nation’s psychiatric hospitals. But this year, the nonprofit agency released new requirements tightening safety standards in an effort to turn the corner, he said.

“Hospitals pay an incredible amount of attention to this — this is devastating for staff when they have a suicide in a hospital,” he said. “Almost all hospitals will probably try to get in compliance as quickly as their budget and planning will allow.”

::

On a recent afternoon, Mia St. John wandered through Runnymede Park, a strip of green nestled among rows of houses in Winnetka in the San Fernando Valley.

When Julian was alive, she found him here most often. Once, she gathered his paintings from the park bathroom.

Under a canopied tree, she sometimes found Julian sleeping, with no comfort other than the cushion of pine needles below his body. On this day, she sat on the tree’s thick, gnarled roots emerging from the soft earth.

Since her son’s death, Mia’s voice is usually fueled with anger, as if she is ready to fight. But here at the park, her eyes softened, she moved slower.

The park offers peace in what feels like never-ending ripples of grief.

On the fourth anniversary of Julian’s death, in November 2018, Kristoff threatened suicide and was later admitted to a psychiatric hospital. He could not cope with Julian’s death, Mia said.

Three months later, Kristoff died from a heart condition that had been exacerbated by excessive drinking, according to his coroner’s report. He had been sober for decades but resumed drinking after Julian died, Mia said.

“He never got over the death of our son,” she said.

After Julian died, Mia sprinkled her son’s ashes in his favorite places across the world: Mono Lake in eastern California, Amsterdam, Beijing, waterfalls in Oregon. She buried most of the remains in a cemetery on the western edge of Los Angeles County.

Earlier this year, she buried Kristoff next to him.

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, you can call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at (800) 273-8255. A caller is connected to a certified crisis center near where the call is placed. The call is free and confidential.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.