How do wildfires start and spread?

Wildfires can start in a variety of ways.

Mostly, they’re caused by humans — by our own activity or our equipment. A study published in 2017 found that 84% of U.S. wildfires were caused by human-related activity; the remaining 16% were caused by lightning. About 95% of fires the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection responds to are caused by humans.

Here are some ways wildfires are ignited in California:

• Power lines/electrical equipment. Electrical lines and related equipment can break in high winds and spark, igniting flames in tinder-dry vegetation that can spread quickly in high winds.

Pacific Gas & Electric Co.’s electrical transmission lines last year sparked the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in California history, the Camp fire, which razed 90% of the town of Paradise, killed 85 people and destroyed more than 13,900 homes. The lines malfunctioned on a dry hillside near a windy canyon.

Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric Co. power lines have also ignited some of the largest fires in modern California history, as has a privately owned electrical system.

• Sparks from vehicles or other equipment. The Airport fire that has burned more than 22,000 acres and injured multiple firefighters in Orange County was sparked by heavy equipment moving rocks in Trabuco Canyon.

In 2018, a trailer with a flat tire that resulted in the wheel’s rim kicking up sparks caused one of California’s most destructive wildfires, the Carr fire in Shasta and Trinity counties, which destroyed more than 1,600 structures and killed eight people last year.

Other common causes are lawnmower blades or metal weed-whackers striking rocks to create sparks, and vehicle collisions. Sparks from a metal grinder jumped into dry grass, triggering the Zaca fire in Santa Barbara County in 2007 — one of the largest in state history.

Chains hanging from a boat or truck trailer can ignite fires; so can hot components underneath a vehicle when parked near dry brush. “You don’t think about it when you drive off to the side of the road,” said Jennifer Balch, lead author of a study on human-caused wildfires and director of Earth Lab at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

• Arson. Arson is a rare cause of the most catastrophic wildfires in California.

The Line fire, which started at the foot of the San Bernardino National Forest in Highland and has burned more than 34,000 acres, was started a Norco resident, law enforcement officials said.

In July, the Park fire that scorched more than 429,000 acres in Butte and Tehama counties was started by a burning vehicle that was sent plummeting down a ravine, authorities said. Police have arrested a Chico man on suspicion of arson in connection with the incident.

In 2006, Raymond Lee Oyler, an accused serial arsonist, used a combination of matches and cigarettes to start a fire at the base of the San Jacinto Mountains, prosecutors said. Five firefighters died fighting the blaze; Oyler was sentenced to death in 2009.

A 23,000-acre fire in Orange and Riverside counties in 2018 was allegedly set by Forrest Gordon Clark; he has pleaded not guilty.

• Campfire. An illegal campfire ignited by a deer hunter caused a wildfire that burned more than a quarter-million acres in mountainous forests near Yosemite in 2013 and threatened a vital supply of water for San Francisco. In a signed affidavit, Keith Matthew Emerald said embers from his campfire blew up the hill and ignited brush. Charges against him were later dropped.

• Cigarettes: Cal Fire responds to an average of 47 wildfires each year caused by carelessly discarded cigarettes.

• Call for help: A deer hunter lost in the backcountry of northern San Diego County set two small signal fires. That caused the Cedar fire of 2003, killing 15, destroying more than 2,800 structures and burning more than a quarter-million acres. The hunter was sentenced to six months in a work-furlough program.

• Faulty wiring. A hot tub’s faulty wiring caused a 76,000-acre fire in Lake County, causing the deaths of four people and destroying nearly 2,000 buildings in 2015.

• Failure to extinguish a previous fire: The Oakland-Berkeley hills fire of 1991, which killed 25 people and destroyed more than 2,200 homes, blew out of control in swift winds after firefighters failed to fully monitor and extinguish a fire the previous day that had been thought to be controlled.

Red-flag warnings in California signal a dry, windy environment ripe for rapid fire growth

• Lightning. It’s not a particularly common cause among California’s most destructive or deadliest fires, but it has caused a fair number of the state’s largest. In 2020, a lightning storm sparked thousands of fires across the state that overwhelmed firefighting resources. More than 1.4 million acres burned by the end of the year.

In 2012, lightning ignited the Rush fire in Lassen County, burning more than 270,000 acres in California; an additional 44,000 acres burned in Nevada.

• Fear of insects. A rancher tried to plug a wasp’s nest in the ground by jamming a stake into the ground. That created a spark that began burning waist-high grass. He tried to smother the flames by tossing a trampoline on them, but that just fed the fire. It caused the start of the larger of two fires that merged to become California’s largest wildfire on record, the Mendocino Complex fire, which burned more than 450,000 acres in four Northern California counties — Colusa, Lake, Mendocino and Glenn.

How do fires spread?

Many devastating wildfires in California are spread by wind.

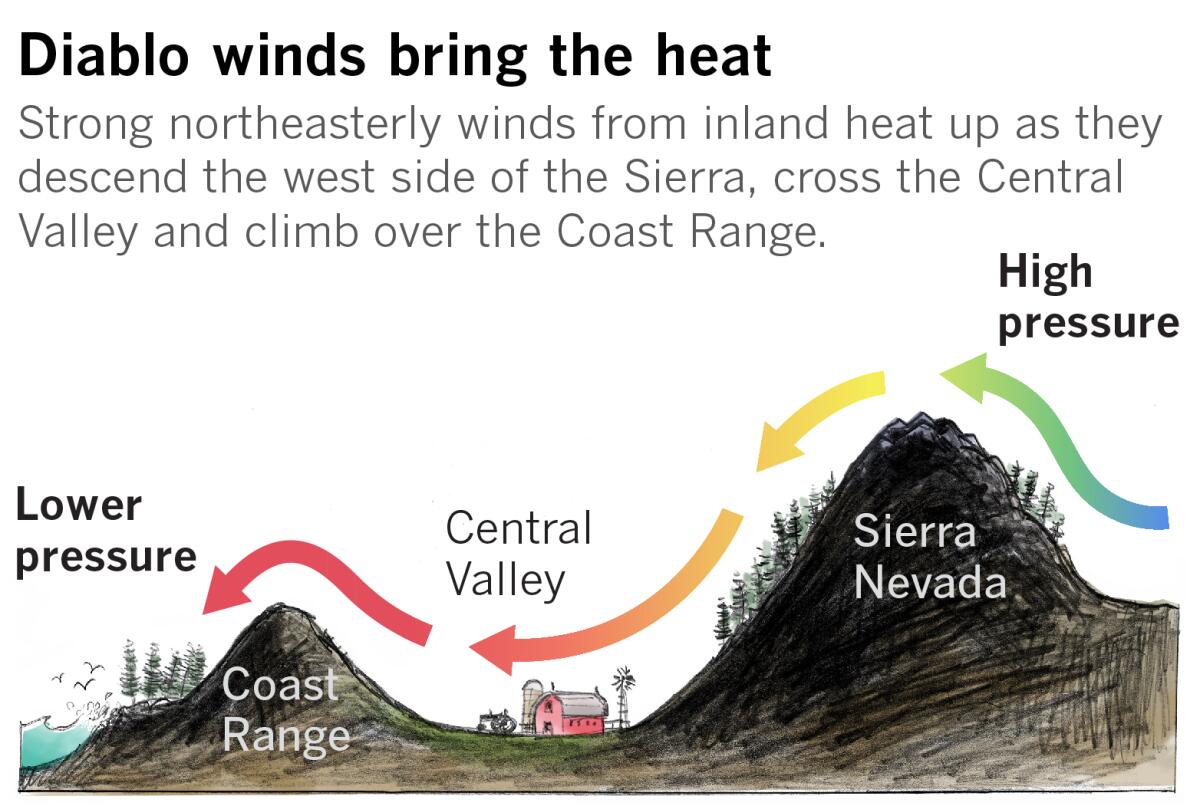

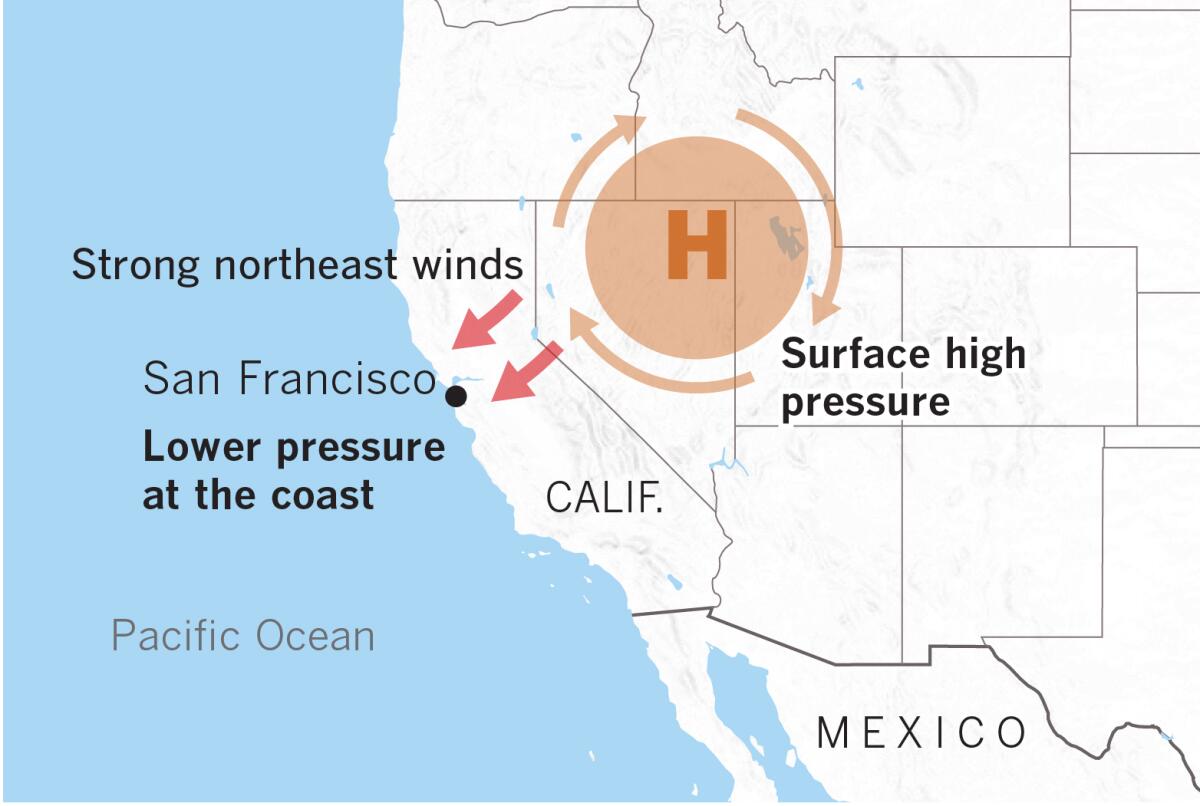

They’re called Santa Ana winds in Southern California and Diablo winds in Northern California. Taken together, they’re called downslope winds.

They’re meteorologically identical. They come from the northeast and head southwest. They occur in the fall and winter, and sometimes in the spring.

They generally peak during the late-night hours and persist through the early afternoon.

They can help bring catastrophic fire weather conditions when they blow as sparks ignite, and they can arrive when vegetation is at its driest point of the year, before autumn rains arrive.

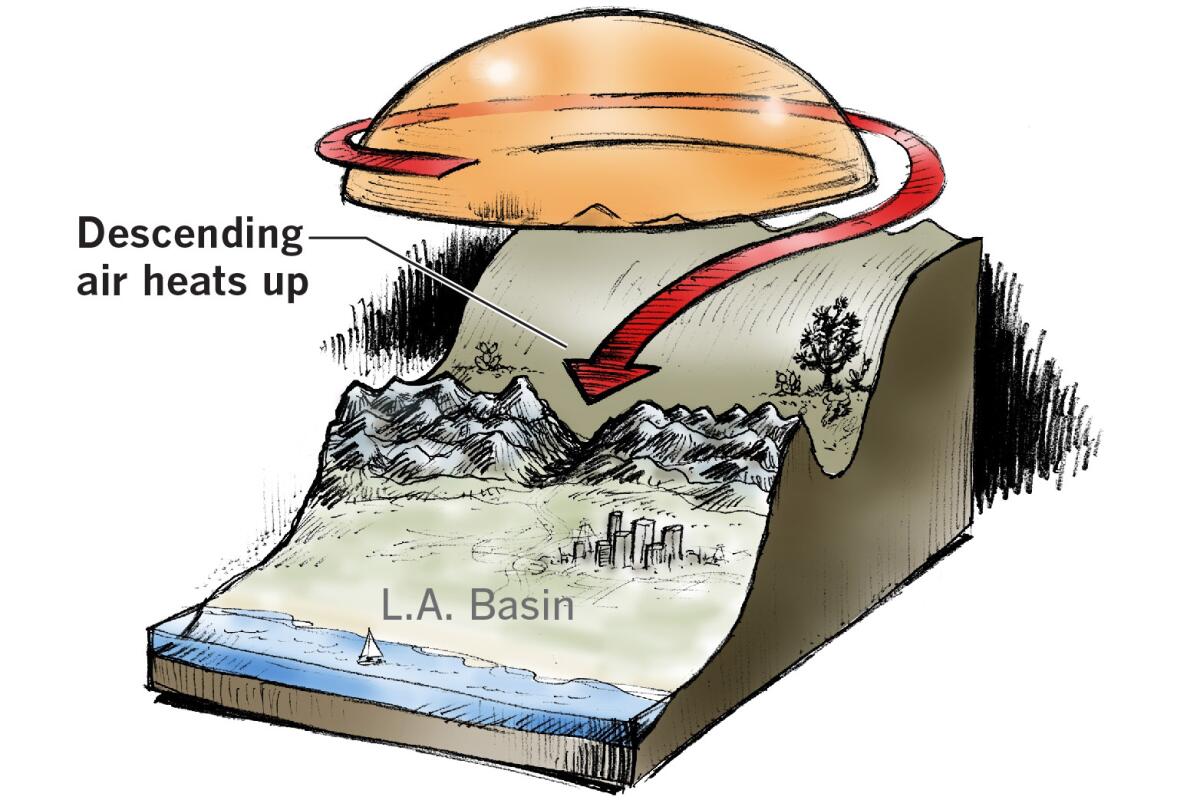

Santa Ana and Diablo winds bring high-pressure air from the deserts of Nevada and Utah howling down the slopes of California’s greatest mountain ranges, searching for lower-pressure voids on the coast.

Not only is dry desert air blowing into California but as the air descends in elevation, it warms and the relative humidity plummets. In extreme events, exceptionally dry air can be pulled from the stratosphere and worsen fire weather.

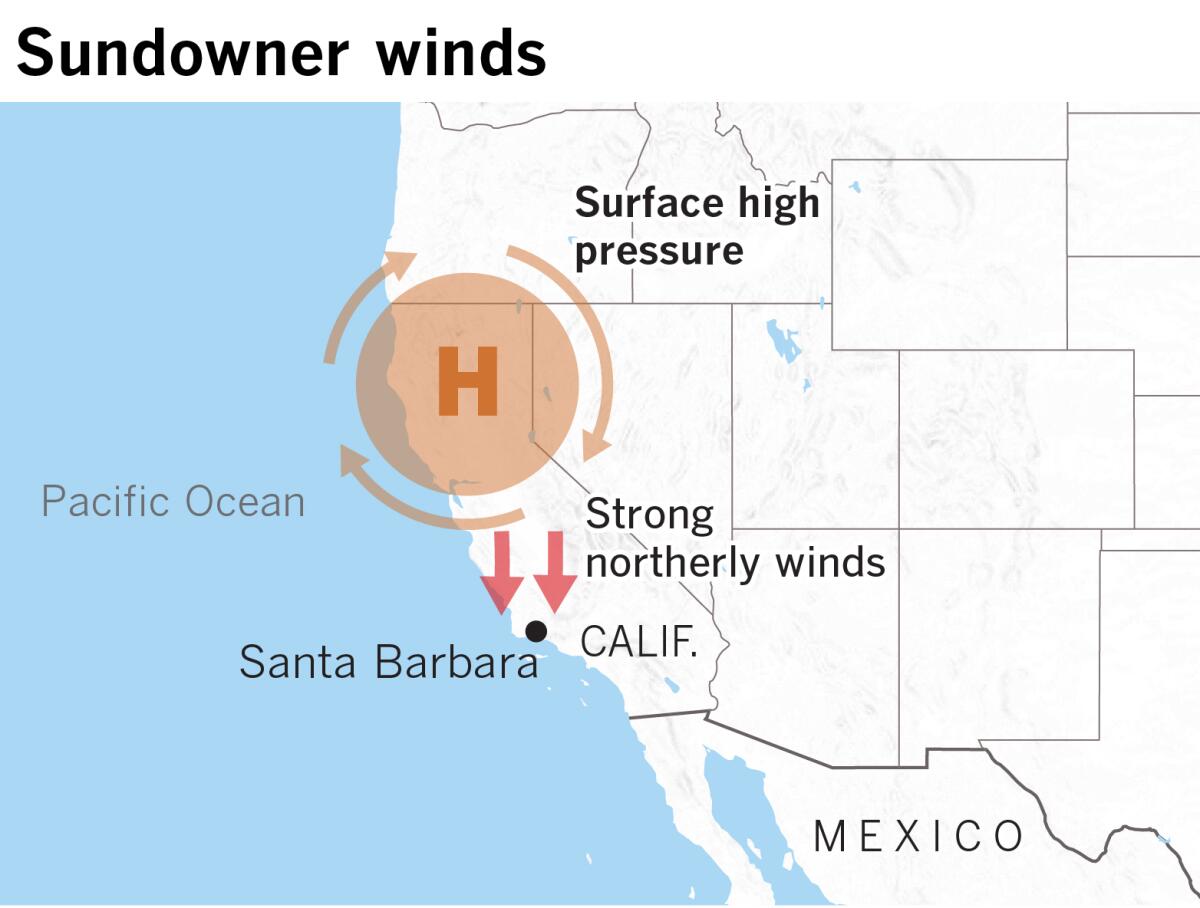

Similar winds that threaten the Santa Barbara area are known as sundowner winds. Strong winds come from north to south, and typically peak in the late spring through the midsummer. Sundowner winds peak during the late afternoon to evening hours.

Are California’s wildfires getting more destructive?

The 10 most destructive wildfires in modern California history have occurred since 1991.

Why is this?

Lots of reasons:

• We continue to build and live in the wilderness. Some experts say we need to stop building homes in wildlands at risk for wildfires. Many elected officials aren’t interested. Authorities continue to greenlight housing developments at great risk for wildfire.

Once a wildfire ignites homes, it can become an urban firestorm — moving horizontally, house to house, as it did in the town of Paradise in 2018. Such fires can be fueled more by igniting homes than the surrounding trees.

• Hotter weather and drier autumns. Hotter temperatures are causing vegetation to get more dried out than ever. Climate change is also linked to drier autumns in California and a delayed onset of autumn rains.

That’s a big problem: Firefighters historically relied on early rains to ease the threat from extreme Diablo and Santa Ana winds that plague California beginning in late September.

Worst winds of season batter California as blackouts and fires spread

• Too many wildfires are followed by intense droughts. Wildlands are getting burned too often, and then are stressed by drought, causing lasting changes to California’s ecology that make the state even more at risk for wildfires.

In Southern California, shrublands are being permanently replaced by invasive grasses, and that raises the risk of wildfires, a Los Angeles Times special report earlier this year said. Invasive grasses don’t anchor soils as well as deep-rooted chaparral plants and ignite easily, fueling more and more fires.

Extended droughts leave behind dead plants that “can leave a dead-fuel legacy on the landscape and contribute to large fires in subsequent years, even in years when precipitation returns to normal,” U.S. Geological Survey fire ecologist Jon Keeley and research ecologist Alexandra Syphard wrote in a study published in the International Journal of Wildland Fire.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.