Due process cases often pit families and schools against each other, instead of being partners in improving special education, critics say

SAN DIEGO — The law says public schools must give students with disabilities the services that meet their individual needs, but parents and districts often disagree on what those services should be or whether a student needs services at all.

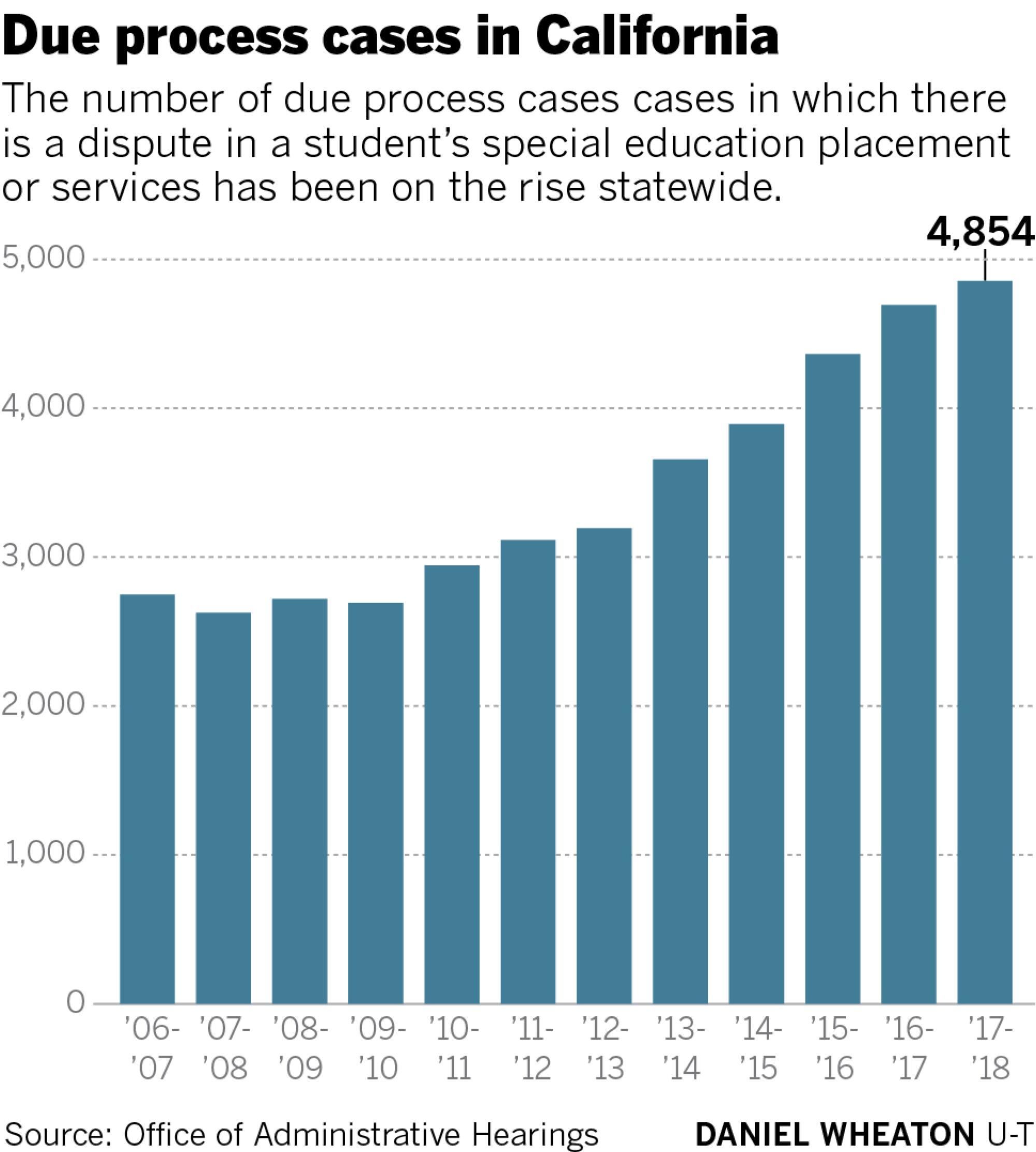

Every year school districts across California settle thousands of these disputes by paying parents and lawyers millions of dollars in what are called due process cases. The number of due process cases has climbed in recent years, tapping into school districts’ already tight budgets.

Last school year, San Diego Unified paid $2 million to settle 128 due process cases, according to district records.

Sweetwater, the county’s second-largest school district, paid $400,000 to settle 31 cases, according to district records. And Poway Unified, the county’s third-largest district, paid $1.1 million to settle 25 cases, according to documents obtained through a public record request.

Much of the settlement money went to reimburse parents for past or future special education services, services that parents say should have been covered by the district. Through due process cases, school districts have agreed to pay for tutoring, private assessments of students and even private school tuition and transportation for students with disabilities.

The money also goes to parents’ attorneys.

Due process cases involve a small but growing fraction of the approximately 725,400 K-12 students with disabilities in California. In 2007-08 there were 2,626 due process cases filed; a decade later, 4,854 cases were filed — an 85% increase, according to state data.

Due process is controversial among families and school districts.

The process is meant to be a legal safeguard that allows families to fight for special education services they think their children need but are not getting from school districts. By filing for due process, parents are exercising their right to appeal special education services or placement decisions.

School districts also can file for due process against families to enforce special education placements or assessments they believe are necessary for a child if the child’s family refuses to accept it.

Due process most often leads to a settlement. In rarer cases it leads to a hearing with a judge, who decides the case.

But critics say due process can be legally intimidating and time-consuming, and it often sets families and school districts against each other as adversaries, rather than partners.

The process also diverts hundreds of thousands of dollars that could be going to students to attorneys instead.

San Diego Unified currently spends up to $610,000 a year paying two legal firms to handle special education matters such as due process, according to board-approved contracts. That’s not including what the district also pays for parents’ attorney fees — in many due process settlements, the school district foots the legal bill for parents.

Poway Unified, meanwhile, paid a legal firm $489,000 to handle special education last school year, on top of $487,000 it paid out to families for their attorney fees.

“The money I’m spending on attorneys is money I can’t spend in other ways,” said Greg Mizel, associate superintendent for Poway. “So if I can resolve a conflict and not spend money on attorneys, I’m way ahead. Now I can use those dollars to support teaching and learning.”

Just because a school district settles a case doesn’t mean the district is admitting that it failed to provide services.

Poway, for example, settles cases even when staff believe they are in the right, in order to avoid spending more on legal costs, Mizel said.

“It really depends on whether we can win. But sometimes we think we can win, but the cost to go to hearing is exorbitant, so it’s not worth it,” Mizel said.

Although due process cases are controversial for their cost and litigious nature, some parents see it as their last resort when their school refuses to give their children services or when their children are failing to make progress in school.

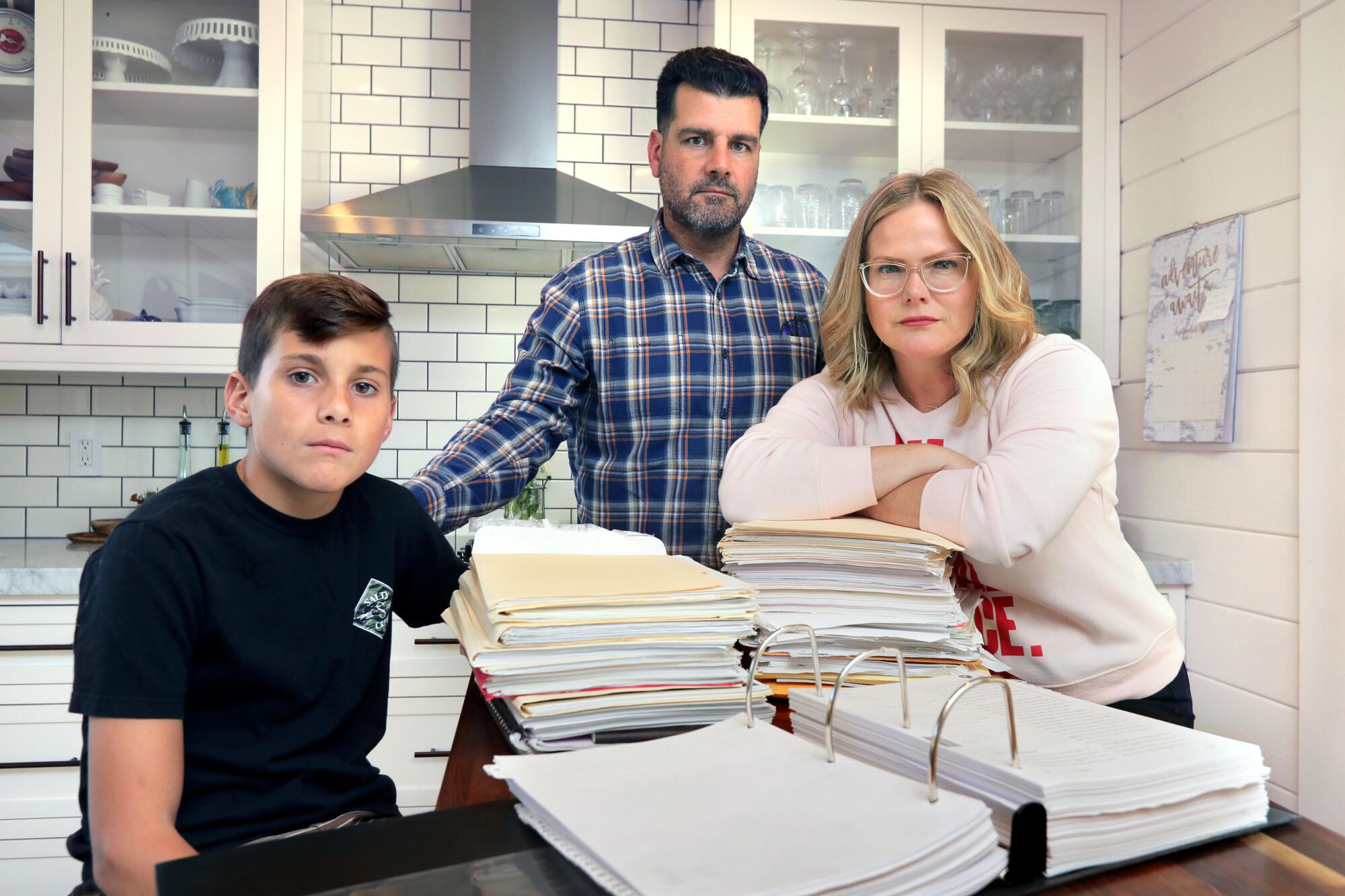

They include parents like Melissa Lazaro, a Poway parent who said she has paid tens of thousands of dollars out of pocket for private tutoring, private school and a special education attorney because her son suffered academically and emotionally while he was at Poway.

Her son, Diego, has dyslexia and dysgraphia — a disability that affects writing — and other challenges.

It wasn’t until third grade that Diego was confirmed to have dyslexia and dysgraphia. School districts are required by law to assess students for disabilities, but when Lazaro asked the district to evaluate her son for disabilities four years ago, the district disagreed and filed for due process against Diego, she said.

She took him to a private practice on her own to have him assessed. That assessment cost her $2,100, she said.

It wasn’t until the end of third grade that Diego started receiving special education services, Lazaro said. It took four meetings with school staff over the course of seven months for the school to write and implement an individualized education program, or IEP, which would guarantee him special education services, she said.

Lazaro believes her son was never on grade level in the time he was at Poway. He bit his fingernails, chewed on his shirt and had meltdowns at home because he was behind his peers and was teased by classmates. He could hardly write two sentences without crying, she said.

In sixth grade, Lazaro took Diego out of Poway Unified to a specialized private school that caters to students with language-based differences. Currently Lazaro is fighting a due process case in court for Poway to reimburse her for the private school tuition and tutoring costs.

In an email, Poway officials said the district has taken steps to address students with dyslexia, including having specialized curriculum and staff trained to use that curriculum at every K-8 school.

“The parents get blamed for the legal fees when, in actuality, the district is choosing to fight them so much that it’s costing everybody. The general public doesn’t fully realize that this is the only way that we can create change and get what our kids need.”

— Melissa Lazaro, a Poway Unified parent

“We agree that many students with dyslexia were struggling in the Poway Unified School District; however, we have made a concerted effort in the last 12 months to address this concern,” officials said.

Some school staff have said they disapprove of parents who switch their children to private schools, then file due process claims to get the school district to pay the bill.

The thousands of dollars that can be paid to settle one due process case could have been used to pay for another school staff member who could have helped several children, rather than just one student, said Sara Finegan, a special education teacher at San Diego Unified’s Hage Elementary.

Settling to pay private school tuition “has never struck us as being the most efficient and cost-efficient way to do anything,” Finegan said.

Still, Lazaro said, it wasn’t until she moved Diego to the private school that, for the first time, he began looking forward to school and now sees himself as a writer. He no longer suffers from anxiety or depression, she said.

“The parents get blamed for the legal fees when, in actuality, the district is choosing to fight them so much that it’s costing everybody,” Lazaro said. “The general public doesn’t fully realize that this is the only way that we can create change and get what our kids need.”

Disputes on the rise

Parents, advocates, teachers and district administrators give varying reasons for why special education disputes are on the rise.

It may be because parents are becoming more savvy about their special education rights, said San Diego Unified Special Education Executive Director Sarah Ott.

Ott also thinks students with disabilities are coming in with more mental health needs, something the district says it is trying to address with additional staff training.

Some teachers and advocates in San Diego Unified think it’s because the district has been offering fewer special day classes, which are classes for only students with disabilities, in order to mainstream more students into general education classrooms.

The idea is to promote integration of students with disabilities with their peers, rather than segregating them into separate classes because they have disabilities.

“We always say students with disabilities are kind of the last class to be desegregated,” Ott said, “and we want to be sure we give access to quality instruction to all our kids.”

But some advocates and teachers say they think mainstreaming is forcing students with a wide variety of needs to fit into a narrower spectrum of choices, which can lead to disputes or problems with assigning incorrect services.

Some also say mainstreaming can be problematic when schools don’t provide enough staff to help students with disabilities integrate into general education classrooms.

As school districts say they struggle to fund special education, some advocates, teachers and parents say they can’t help but think that money plays a role in causing special education disputes.

“It’s money. Yeah. It’s money,” said Dayon Higgins, a special education advocate who has worked with families for about two decades. “It really comes down to dollars and cents.”

School districts frequently point out that they are not getting enough funding to keep pace with rising special education costs. The number of students with disabilities has been rising, but many districts’ overall enrollment has decreased, meaning they receive less state funding.

At the same time, districts are not allowed to say that they can’t provide proper services for a student with disabilities because they lack money or staff. Federal law says every student with disabilities must receive individualized, personalized services depending on their needs.

But teachers, parents and advocates say they have encountered cases in which students were denied services or did not get services promised by the school in their legally binding IEPs.

Higgins said one of her San Diego Unified student clients, who injures himself to the point of bleeding, got an IEP in January that says he needs a one-on-one aide. Nine months later, he still has no aide, Higgins said.

Last school year, scores of San Diego Unified special education staff members packed a town hall meeting where some staffers said students were missing out on services they were supposed to receive because the district was under-staffing schools. Staff said speech language pathologists were putting students on wait lists for services because their caseloads were full, for instance.

“By not being able to provide all the services a student needs, the district is forcing us to be in a relationship with parents that is no longer a partnership and is hostile in many ways, which is stressful.”

— Sara Finegan, special education teacher at Hage Elementary

Two school years ago, Finegan said, she had as many as 35 students in her classroom at a time. Two of her students were supposed to have one-on-one aides helping them several hours a week, but they ended up getting that assistance no more than a few hours the whole year, Finegan said.

“By not being able to provide all the services a student needs, the district is forcing us to be in a relationship with parents that is no longer a partnership and is hostile in many ways, which is stressful,” Finegan said.

San Diego Unified said in a statement that teacher allocation and aide support are based on school enrollment, students’ IEPs and student needs. The district has a committee handling concerns about under-staffing or large class sizes.

Seth Schwartz, an attorney whose law firm has represented parents in several due process settlements across the county, said he has seen a lack of funding for services and a lack of training by schools play a big role in his clients’ cases.

“If you’re not trained correctly, you’re going to make mistakes. If you’re not funded correctly, you’re not going to be able to provide everything you might need to provide,” said Schwartz, whose law firm has grown from two to seven attorneys since 2012.

To address staffing shortage concerns, San Diego Unified agreed this year to set a lower caseload cap of 20 students for certain special education teachers and promised to pay stipends to teachers when their caseloads exceed the cap.

But the agreement doesn’t help teachers who work with students with moderate-to-severe disabilities, nor does it address the staffing of other special education employees, such as aides or speech language pathologists.

Still, Ott said, the district has hired more staff, such as speech language pathologists and special education teachers, for this school year.

At Hage Elementary, there are still staffing challenges even with the new caseload cap, Finegan said.

There is one special education teacher for students with mild-to-moderate disabilities and one full-time aide for all the school’s transitional kindergarten through second-grade students, meaning it’s likely at least one student is not getting the full aide support required by their IEP, Finegan said.

She also said one of the school’s special education teachers is having her hours reduced from full-time to part-time while more students are being assessed for potential new IEPs.

Schwartz said he believes the biggest factor that creates disputes between families and schools is a breakdown in communication between the parents and the district.

“As long as a school district is communicating with a parent in a reasonable way there’s a good chance the parent will not go for help, even if there are genuine disagreements,” Schwartz said.

Minimizing disputes

Districts say they are taking steps to minimize special education disputes.

San Diego Unified is increasing special education training for school staff, Ott said.

For example, Ott said the district held a three-day special education training institute this summer for principals, vice principals and instructional coaches, teaching them how to write IEPs for students and how to provide quality instruction to students with disabilities, among other things.

A district coach also is working to develop additional training for non-teaching special education staff, Ott said.

Poway Unified has been working to decrease due process cases by resolving them with a process called alternative dispute resolution. There are no lawyers involved in alternative dispute resolution, just the district’s special education director, parents and a third-party arbitrator to help facilitate.

Carrie Holliday, a parent of a Poway student with autism and bipolar disorder, used alternative dispute resolution to get her son, Oliver, his current special education placement.

The previous private schools Oliver had been placed at were nightmares for him, she said. One residential school in Texas did not ensure that he had clean clothes or that he went to school at all, she said.

At another school, multiple staff often physically restrained him rather than using less restrictive de-escalation strategies, Holliday said. Holliday quit her job because Oliver was missing so much school and needed so much help, she said.

Before alternative dispute resolution, Poway Unified was prepared to send Oliver to a private school where his classmates would have been nonverbal, Holliday said. Oliver is highly verbal, she said.

After alternative dispute resolution, the district agreed to place Oliver at his local middle school in the district’s PAL program for this school year, which provides individualized and small group instruction for students with disabilities, Holliday said. He also has a one-on-one aide.

Both Holliday and her special education advocate, Higgins, had glowing feedback about alternative dispute resolution.

“It was much more successful than the due process, where you sit with lawyers,” Holliday said. “This was much more of a conversation of what does he need, how do we do it.”

Since then Oliver has been doing better, Holliday said. He is gradually getting used to going to school again, and his teacher and aide know how to calm him down by giving him space without restraining him, she said.

“We’re on the right track,” she said.

Taketa writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.