Column One: He’d been kept alive with tubes for nearly 17 years. Who is he, and is it possible he’s conscious?

SAN DIEGO — It was his 34th birthday and the icing from the cake was his first taste of food in almost 17 years. He didn’t react when the dollop of chocolate settled onto his tongue. Maybe his taste buds had stopped working. Or maybe he had just forgotten what real food was like.

What else had he missed all these years he’d been confined to a hospital bed? How long had it been since he heard a dog bark or a baby cry? Since he squinted from the sun in his eyes or felt rain on his cheeks? Since he was held by someone he loved?

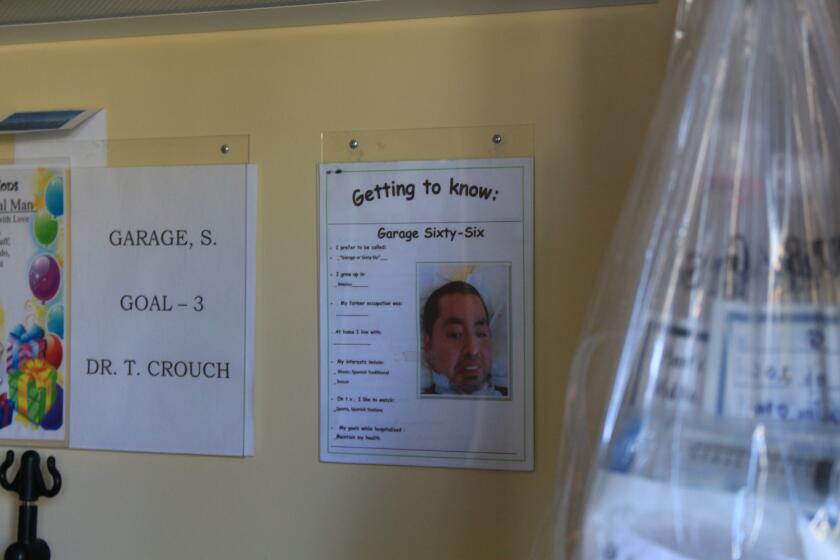

He’d been kept alive with breathing and feeding tubes, and until a month before his birthday party in January 2016, he’d been known only as “Sixty-Six Garage.” That was the name on his hospital bracelet, the name on the door to his room, the name on the sign above his bed, the name the state of California used to pay the nursing home for his care.

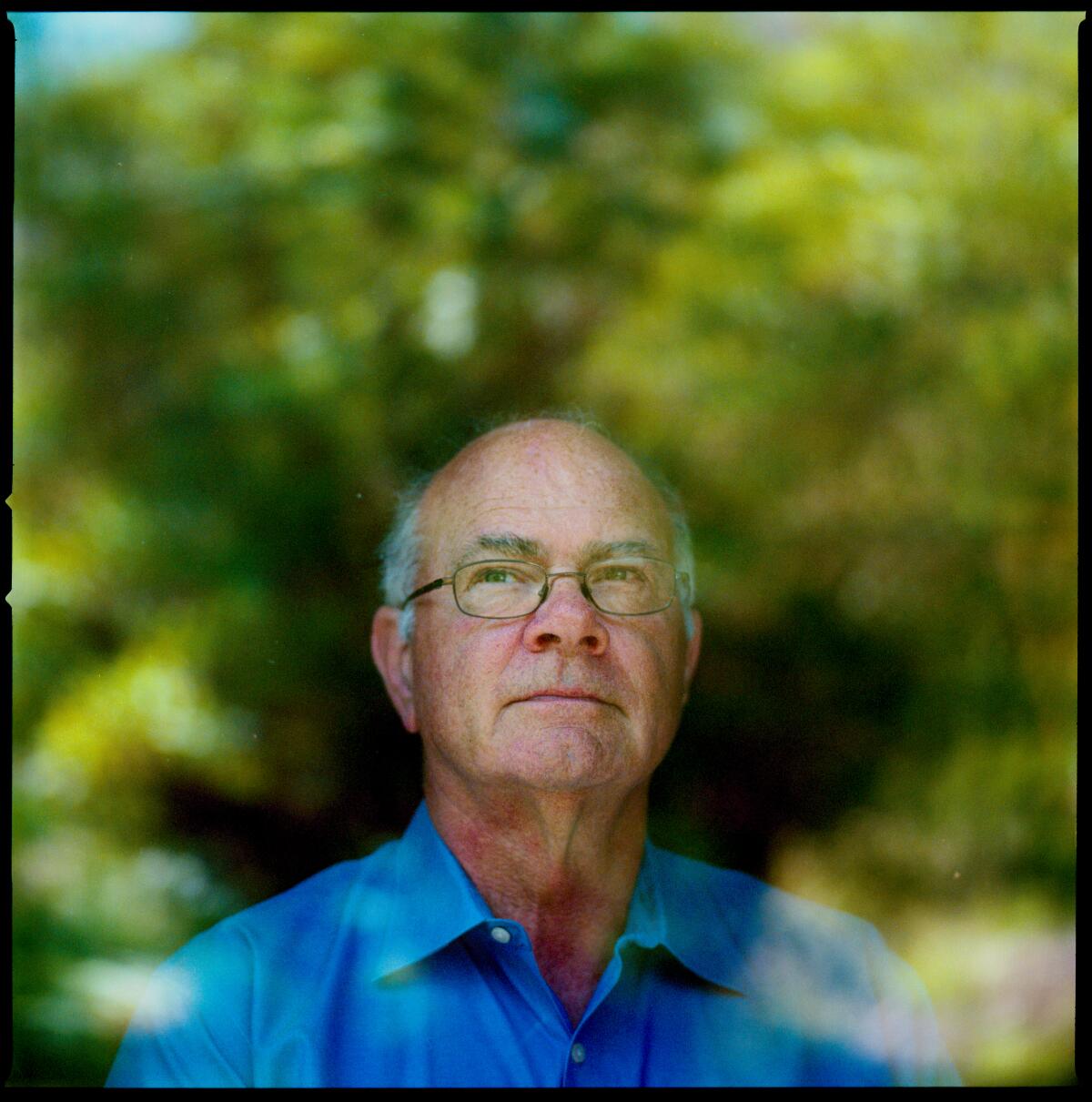

It’s the name he probably would have been buried with if Ed Kirkpatrick, director of the Villa Coronado Skilled Nursing Facility, hadn’t let me into Room 20 — Garage’s room. I’d already spent nearly a year at the Villa, reporting on people on life support. I’d documented what life was like for people kept alive this way — more than 4,000 in California alone — and the life and death choices their families were forced to make. Now Kirkpatrick was trusting me to tell Garage’s story.

“He’s a human being. And 16 years is too long to go without knowing who this was,” Kirkpatrick later said of his decision. “We need to CSI the hell out of it.”

Kirkpatrick shared what little he knew of Garage’s story. In 1999, he had been in a crash in the California desert, somewhere near the U.S.-Mexico border. When first responders found him, he had only a Mexican phone card and a few pesos in his pocket, so they assumed he had entered the country illegally. He was airlifted to a hospital in San Diego, and when there was no hope he’d recover, he was transferred to the Villa.

The name “Sixty-Six Garage” came from a place near the accident, where Garage’s vehicle was towed, Kirkpatrick told me. That, like so much of the lore surrounding Garage, would turn out not to be true.

Kirkpatrick said Garage was in a vegetative state, which meant he wasn’t aware of his surroundings or even himself. So each time I saw him, I looked at him as though he wasn’t a person — like he was someone with no thoughts or feelings. Until one day, early in 2015, he smiled at me.

Despite all the research I had read and despite knowing that a smile can be a reflex, I was convinced in that moment that Kirkpatrick was wrong — Garage was still in there.

For the next two years I would track down the people, documents and scientific evidence I needed to understand how an ordinary Mexican teenager lost his humanity after crossing the border, kept alive by a system that didn’t care enough to learn his name.

Finding Garage’s name turned out to be the easy part.

The tough part was navigating the blurred lines that separate consciousness from unconsciousness — and figuring out whether that smile was really a smile.

Room 20

The hallway to Room 20 is a dividing line of sorts. On one side are people who are old and frail but can breathe and eat on their own. On the other are people kept alive by tubes and machines, who are either unconscious or have no way of indicating otherwise. Room 20 is on this side of the hallway.

An old guy the staff calls Papa is in the first bed. He had a stroke years ago. Unlike his two roommates, he appears aware of his surroundings, able to grunt when he is in pain, or wants his TV on, or when the plastic collar around his neck, which keeps the blue oxygen hose attached to the hole in his windpipe, is too tight.

Next to Papa is a 22-year-old bicyclist who was hit by a car going 55 mph on a dark California highway and then run over by a second car. He stares mindlessly at the ceiling, as though he is frozen in place, caught in a limbo that defines this unit.

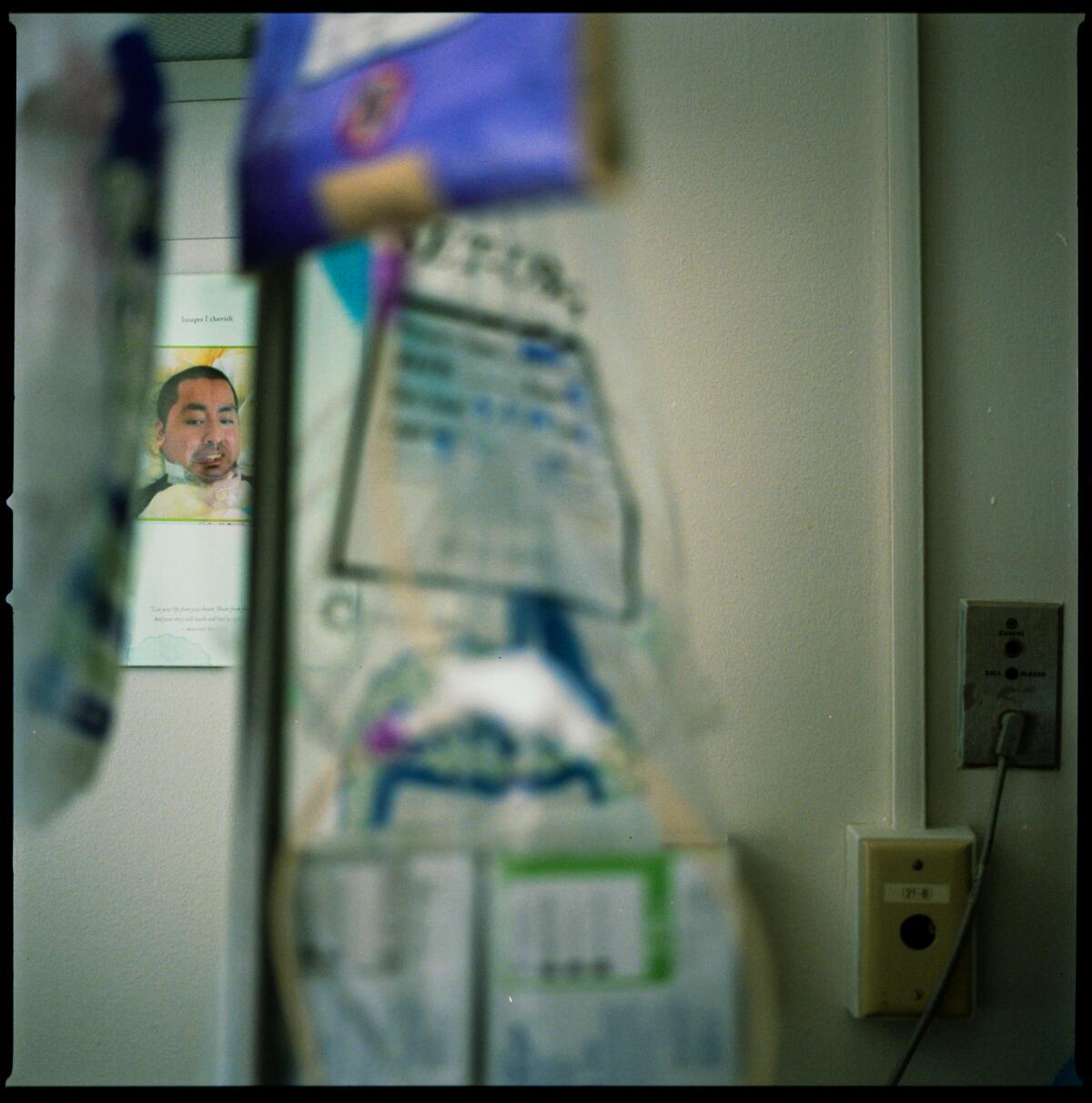

Closest to the patio doors is Sixty-Six Garage. He is attached to two tubes, one connected to a hole in his throat, the other to a hole in his stomach, the only way he has been fed since 1999.

A new L.A. Times Studios podcast about the search for a man’s identity.

Room 20 is on a unit designated “subacute” by the state of California, but pejoratively known as a “vent farm” by some doctors. More than 4,000 people are on life support in about 125 facilities across the state. The number includes only those covered by Medi-Cal, the state’s insurance program for the poor and disabled.

The nursing home guesses Garage was born sometime in 1960, but to me it’s obvious that he is a young man — in his 30s. Under the flimsy sheets, his torso makes only a small outline, like that of a teen-age boy.

Garage has thick dark hair that is usually shaved about half an inch from his scalp. His face is round, his eyelashes long and straight. His face is supple and his skin hadn’t taken on the translucent sheen like the others down the hall. His full lips are often coated with the pasty white film that accumulates on a perpetually dry mouth.

I visited Garage regularly and learned the routine of his life.

He appeared to move in and out of consciousness, sometimes smiling like a small child, other times staring at the ceiling and striking his right leg on the corner of the bed for hours. There were days when he looked catatonic, and days when he’d stare wide-eyed as though he was seeing everything around him — the feeding machine, the TV that hung on the wall across from him, and me — for the first time.

Each day he was changed and turned. Liquid food and medicines were pumped into his stomach — he was on seven medications, including an antidepressant.

Some days, he was placed on a gurney for a shower. A hydraulic lift was used to lower him into a special wheelchair so he could be moved into the hallway or activities room. He seemed to hate leaving his bed. He’d kick at the nursing assistants, and when he was finally settled into his chair, the corners of his lips would turn down and he’d have tears in his eyes.

One day I wheeled him outside, into the courtyard. But the traffic noise, the breeze, the openness of the sky — it all seemed to frighten him. He wouldn’t stop crying, so I took him back to his room.

Most of the time, he lay in bed with the TV on. His pillow was often stained with blood because the friction between the fabric and his scalp created lumps that bled.

Sometimes Garage opened and closed his mouth as though he wanted to speak, but the only sound that came out was a gurgle — the sound of mucus collecting in his chest. The gurgling grew louder when he appeared upset — especially when he was about to be suctioned.

Suctioning was essential to Garage’s survival because he couldn’t clear the mucus from his throat like a healthy person. If he wasn’t suctioned every few hours, the mucus might clog the hole in his throat and cut off his oxygen supply.

I watched the procedure dozens of times.

A nurse or nursing assistant would insert a narrow plastic tube into the hole in his throat and remove the mucus with a small vacuum. Garage’s cheeks would inflate and his face turned red, like a balloon atop his tiny, rigid body.

Kirkpatrick said the process is “like waterboarding,” a form of torture where water is poured into a person’s breathing passages to create the sensation of drowning.

“It’s the same physical concept and you’re doing it seven, eight, nine times a day to a person,” Kirkpatrick said.

I learned that counting on my fingers in Spanish seemed to comfort Garage as the tube went down his throat.

“Uno, dos, tres, cuatro, cinco” was the only Spanish I knew. I’d repeat it until his arms relaxed, the red faded from his face and the gurgling softened, as though he were a child who had been hushed.

Garage’s expressions and movements often mimicked those of an infant. He’d reach for the baby toys I brought him and try to copy me when I showed him how to press the buttons or tap out sounds on the hard plastic. His hand would flail and his fingers would reach for the buttons, but he didn’t have the aim or strength to push hard enough to trigger the toy into action.

One evening, I held up a plastic baby mirror and tapped it with my index finger until it made a “click, click” sound.

Garage reached out with his left hand and tried to copy my movements. After about the third try, his finger hit hard enough to make a sound. He smiled and made eye contact with me, as though he knew — we both knew — that he’d done something remarkable.

Between 2015 and 2017, I spent hundreds of hours sitting on a folding chair, observing and taking notes, trying to document the life that was playing itself out in that small corner of Room 20. When I wasn’t there, I was often traveling to California’s Imperial Valley, not far from the U.S.-Mexico border, to figure out how Garage had ended up in this place.

The accident

The Imperial Valley supplies many of the vegetables the rest of the country eats, and about half of the workers who pick those vegetables are in the country illegally. This is where Garage was headed when the crash happened, according to the 16-page accident report I eventually found.

The California Highway Patrol had destroyed the report years ago, but I tracked down an unredacted copy at the Imperial County Public Works Department, which reviews accidents within its jurisdiction. The report became my roadmap. I found witnesses, first responders and a man who survived the crash to piece together what happened on a clear blue day at an intersection in the middle of farm country.

The sun was just coming up that Thursday, June 10, 1999, when Garage and at least three other men climbed into the back of a 1988 Chevy pickup and hid under a pile of suitcases. The driver steered the truck down Bowker Road, a two-lane road that begins at the border.

Here in the valley, the topography can trick you into believing you’re somewhere in the Midwest: lonely farmhouses planted in the middle of vast fields, winds that pick up at sunset and smell almost electric. But the white-and-green Border Patrol vehicles parked every few miles along the road are a reminder this is not Middle America.

In 1999, the Imperial Valley was one of the busiest corridors in the country for Border Patrol apprehensions. In those days, only a single fence or nothing at all marked some parts of the border between San Diego and Tijuana. So many migrants were streaming across that warning signs were posted on nearby freeways showing silhouettes of a man and woman running with a child.

Bowker Road passes by farmers’ fields, an occasional smattering of houses, a gas station and an elementary school. Nine miles north of the border, Bowker intersects with Evan Hewes Highway, a smooth, flat four-lane road.

How did an unconscious man remain unidentified for more than 15 years? In a brand-new podcast brought to you by L.A. Times Studios, investigative reporter Joanne Faryon set out to answer that question.

There’s a stop sign on Bowker. But that morning, the pickup’s driver ignored it and sped into the path of a 1978 Toyota Celica.

The two men in the Toyota — Abel Ramirez, 33, and Gregorio Flores Mendez, 31 — were carpooling to work on a nearby farm.

Mendez, in the passenger’s seat, saw the truck. It “was going fast, like 50 miles per hour,” he said through an interpreter.

He also saw the lights of a Border Patrol vehicle coming up fast behind the truck.

“They were chasing them,” Mendez said.

Ramirez hit the brake, but it was too late. The Toyota slammed into the truck with such force that it ripped Ramirez’s seat belt in two. The pickup flipped and landed on its side in the middle of the intersection. At least nine people were in the truck, including the driver. He and as many as four other men got out of the truck and ran north. Four more men were too injured to flee.

Two broke their backs and were taken to hospitals. Another landed on the dirt median that divided the lanes. He died the next day. Garage landed on the asphalt in the westbound lane. He was covered in blood.

The sound of the crash woke Brenda Villegas, who lives near the intersection.

“I opened up the blinds and all I saw was a pickup truck on its side and a bunch of people running,” Villegas said. “And then I heard the helicopters. And they were like around this area trying to find the people.”

According to the CHP accident report, it was a Border Patrol helicopter that Villegas heard.

“I thought, well that was fast. You know, right after the accident. Usually the police and them come later,” Villegas said.

The crash left Mendez hospitalized for eight days and off work for a month. Ramirez, the Toyota’s driver, refused medical treatment and went to work on the farm that day. He died six months later from an aneurysm, Mendez said.

I told the Border Patrol what I’d learned about the chase and the crash, and said I had questions about their pursuit policy and Garage’s accident. The agency declined to comment.

I heard a lot about Border Patrol chases while I was in Imperial County: that they were common, and often unreported back in the 1990s. In 1992, one chase began on Interstate 15 near Temecula in Riverside County and ended close to a high school. Six people died, including four teenagers. That crash led to changes in the Border Patrol’s pursuit policy. Agents had to stop the chase if the risks outweighed the danger posed to the public if the suspects got away.

That policy is still in place today. In April, a ProPublica and Los Angeles Times investigation found that in the last four years, 22 people were killed in Border Patrol chases and at least 250 people injured. One 6-year-old girl wound up on life support.

Garage was taken to a hospital in El Centro, then airlifted to a San Diego trauma center. He underwent surgery to reduce the swelling in his brain and had the feeding and breathing tubes inserted. With no one to make a choice on his behalf — to do everything medically possible or to let go — the system almost always chooses life.

It was there that he was given the name “Sixty-Six Garage,” randomly chosen from a long list of aliases the trauma team had created using a theme — such as buildings or houseplants — and a number. Sixty-Six Garage was a placeholder, in lieu of John Doe, until his identity could be confirmed through a relative, driver’s license or fingerprints.

It was never supposed to sound like it belonged to a real person.

The absurdity of the name escaped the state of California. It approved Medi-Cal funding for Sixty-Six Garage, allowing him to be transferred from the hospital to the Villa. So far, California has paid more than $4 million for Garage’s nursing home care.

Ignacio

The first legitimate lead about Garage’s identity emerged in summer 2015, after Enrique Morones, founder of the migrant rights advocacy group Border Angels, got involved. I had been reporting on Garage for a San Diego news site and interviewed Morones.

“Why hasn’t anybody done anything?” he wondered. “Fifteen years! That’s a lifetime. And, to me, that is unbelievable.”

I introduced Morones to Kirkpatrick and together they formed a committee to find Garage’s identity. Chris Harris, a Border Patrol agent, was also part of the group, along with officials from the Mexican Consulate.

Morones took Garage’s story to the chief of the Border Patrol in Washington and asked for help. Harris suggested that a Border Patrol forensics team fingerprint Garage. He figured there was a good chance Garage had tried to cross the border before and might be in the agency’s database.

His hunch turned out to be right.

Garage’s prints matched those of a Mexican teenager named Ignacio, who had been detained three months before the crash. The Mexican Consulate located his birth certificate and tracked down a woman in Ohio it believed was his sister. Months later, DNA tests confirmed with 99.5% certainty that she was Garage’s sister.

The day after the news arrived, Kirkpatrick and I walked from his cramped office, through the maze of hallways that led to Room 20. It had been more than a year since I first reported on Garage — or Ignacio — and for some reason I clung to the improbable notion that he would react to his name. That all he needed was to hear it.

“Ignacio, Ignacio,” Kirkpatrick bellowed as he stood over Ignacio’s bed.

“Is your name Ignacio?” he asked even louder, as though raising his voice might jar Ignacio back to life.

Andy Walsh, Ignacio’s nurse, repeated the question in Spanish.

“Se llama Ignacio?” Walsh asked.

Ignacio looked at Walsh, then me, then Kirkpatrick. It was a look of bewilderment, not recognition.

“Lift your left hand if your name is Ignacio,” Walsh instructed in Spanish.

Ignacio didn’t lift his hand.

“Blink once, blink twice,” Walsh tried again.

He didn’t blink.

Little changed for Ignacio after that day. The nursing home staff often forgot to call him by his real name. For years they had known him only as “Garage,” or “Mr. Garage,” or “Sixty-Six.”

The name on his hospital bracelet stayed the same for two years because no one seemed sure that Medi-Cal would pay for his care if he were no longer Garage.

To learn about who Ignacio was as a boy and about the man he dreamed to be, I traveled to a small town in Ohio, where I sat with his sister at her kitchen table.

Nacho

Juliana was 38 when we met in 2016. She looks like Ignacio. They have the same nose, the same eyes.

She crossed into the United States a few years after he did, traveling mostly on foot through the desert. She ended up in Ohio, where she found a job in a factory and rented one side of a duplex in a working-class neighborhood. She lived with her three American-born children. The oldest was 12.

Juliana assumed Ignacio was dead.

“That’s what we were expecting to find out, that he had already died crossing the border,” she said in Spanish, through a interpreter. (Their last names are being withheld because they are in the country without authorization and could face deportation.)

The one thing she never imagined was that he was being kept alive with machines in a California nursing home.

The Ignacio that Juliana remembered was athletic — he played soccer and basketball. He had a nice voice. He liked to sing when his favorite songs played on the radio.

His family called him Nacho.

Both of their parents had been previously married, and Ignacio was the youngest of their 12 children. They lived in the state of Oaxaca, on a ranch outside San José de las Flores, a village more than 2,000 miles from California’s most southern border. About 1,000 people live there. Half the houses have dirt floors.

At home, the family spoke Mixtec, an indigenous language; at school, Ignacio learned to speak Spanish. He was the only one in his family who went to school past the primary grades.

“He didn’t want to work like all of us, as a field worker,” Juliana said. “He was studying because my mom always told him he had to study.”

But when Ignacio was 15, plans for his future collapsed. His parents were caught up in a political dispute and killed. A month later Ignacio quit school and went to work in the fields. He returned to school a year later, but dropped out when he couldn’t pay for the uniform and soccer cleats he needed.

In March 1999, when Ignacio was 17, he decided to do what so many teenage boys around him were doing. “He was going to cross,” Juliana said.

An older brother urged him to stay and finish school, but Ignacio insisted. He’d first go by bus to Tijuana or some other border town. Then a coyote would lead him and the other boys on foot or by car into the United States. The trip would cost $200.

A few weeks after Ignacio left home, he called his sister to tell her he’d been caught by the Border Patrol. He told the agents he was 18, because if they had known the truth — that he was still a minor — they would have detained him until they located his family instead of releasing him in Mexico.

Ignacio was still determined to get to the United States. He told Juliana he had found a job picking chiles. As soon as he saved enough money, he was going to try to cross again.

The Reunion

Nearly 17 years after that phone call, Juliana saw Ignacio — on my iPhone. I was standing next to his bed when her call came in. I put the screen in front of his face and watched as he stared at my phone and at Juliana looking back at him.

Juliana cupped her face in her hands when her brother’s face filled the screen. When she spoke, Ignacio turned his head to look at me and then back at his sister.

Juliana told him she missed him and would do her best to come to see him.

Sometimes she said nothing and just stared at her brother’s face. His cheeks and chin were now dotted with the tiny black flecks that surface after a shave, a sign he was no longer the boy who’d left home.

A few weeks later, in February 2016, Juliana flew to San Diego to be reunited with her brother. The Mexican Consulate arranged the trip and sent an escort with her. Still, the journey was risky. If she had been questioned by immigration officials along the way, she could have been deported, leaving her three U.S.-born children behind. The consulate had an attorney on standby, just in case.

Neither Kirkpatrick nor I witnessed the reunion. I was out of town and he was in the hospital. Kirkpatrick had fallen into a bed of hot coals on a camping trip and had third-degree burns on his hands.

The nursing assistants who worked that weekend told me they believed Ignacio recognized his sister. They said they could tell by the way he looked at her. One of the Mexican officials who was there said the reunion was bittersweet. Juliana told her brother that nine of their 10 siblings had died while he was at the Villa.

Consciousness

The stench stopped me first. Then the fear that I’d be hit with a spray of the excrement that with each strike of his foot on the mattress burst into tiny pieces.

Ignacio’s diaper had come loose and he was covered in his own feces. He was staring up at the ceiling as though he was in a trance.

It was the summer after his reunion with his sister and I’d been reporting on Ignacio at the Villa for about 18 months. Until this moment, I had convinced myself he was a thinking and feeling human being — a person capable of connecting to his environment and to me.

I’d never seen him like this, oblivious, almost animalistic.

He was making a loud gurgling sound, a sign that he needed to be suctioned. I called for help, and when a nurse arrived, she took one look at the room and left to get a plastic shield to cover her face.

Ignacio flailed his arms as the nurse tried to insert the tube from the vacuum into the hole in his throat. I crouched low, crept toward his bed, and knelt down beside him. I put up my right hand where he could see it, and slowly counted on my fingers, “uno, dos, tres …”

Ignacio stopped kicking, his arms went limp and the nurse began the procedure.

Maybe Ignacio was in a vegetative state after all, I thought. Maybe his smiles were reflexes and the tapping on the toys random. Maybe the signs of life I’d seen were just the haphazard motions of a brain so damaged that it strained just to keep his body warm and failed at nearly everything else. Did Ignacio, the man, still exist?

For answers I asked Caroline Schnakers, an expert in diagnosing consciousness, to come to the Villa to test Ignacio. Schnakers is the assistant director at the Casa Colina Research Institute in Pomona. She’s an expert at administering the JFK Coma-Recovery Scale Revised, a test that rates patients in six categories and scores them out of 23 points.

Doctors get it wrong about 40% of the time when they diagnose people as being in a vegetative state, Schnakers said. Her work has demonstrated they are more likely to be minimally conscious. In other words, they’re aware, some of the time.

With the help of a video interpreter, Schnakers gave Ignacio a series of commands.

“Look at the spoon,” she said. Then she put the spoon close to his lips to see whether he would open his mouth.

Sometimes he did.

“Try, try to stick out your tongue,” she said.

Ignacio didn’t respond.

“Try to close your eyes a long time.”

He didn’t close his eyes.

Ignacio couldn’t do most of the things Schnakers asked during the hourlong test. He couldn’t distinguish a cup from a pen. He showed no recognition when she held up an old photo of him and his mother, no recognition when she played a recording of Juliana’s voice.

But Schnakers confirmed what I had believed that day so long ago, when Ignacio first smiled at me. He scored 14 out of 23 on the test, which meant he was conscious at least some of the time.

He could hear, but he couldn’t understand language. He could reach for objects, like a cup, but he didn’t recognize what the object was for.

He could also feel pain, Schnakers said. So each time he was suctioned, six or seven or eight times a day, he felt it.

“That has to be addressed ... because pain is complicating recovery,” Schnakers said.

Schnakers thinks Ignacio probably lives only in the moment. When someone is with him, reacting to him, he reacts back. But when they leave the room, they no longer exist for him.

That is the thing I continue to hold onto — that time has no meaning for Ignacio. That he has no idea he’s lying in a hospital bed. The same place he’s been for nearly two decades.

A birthday party

Ignacio’s 34th birthday party — his first birthday celebration since he left home in 1999 — was a big event at the Villa. One worker called it Ignacio’s rebirth.

The activities room was decorated with balloons, and music played on a boom box. Families of other subacute residents were there, along with patients from the other side of the hallway — people who were conscious and could breathe on their own. Juliana listened from Ohio, on speakerphone.

Ignacio didn’t look happy, probably because he was propped up in his wheelchair, something he’d always appeared to dislike. That brief lick of chocolate, the music — nothing cheered him up. When everyone gathered around to sing “Happy Birthday,” he just stared straight ahead.

Then the group began to sing in Spanish.

“Feliz cumpleaños, feliz cumpleaños a ti.”

For a brief moment, Ignacio looked out at the crowd in front of him, and smiled.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.