Charles Manson’s murderous imprint on L.A. endures as other killers have come and gone

Hearing the retired prosecutor recount the bloody crimes that scarred Los Angeles, it is easy to forget that the savage murders happened half a century ago.

Stephen Kay runs one hand slowly down his cheek, describing the mark a thick rope scraped along actress Sharon Tate’s face. The rope was tied around her neck and looped over a living room beam in her rented Benedict Canyon home. She was 8 ½ months pregnant. Clad in just a white bra and panties. Still alive, though not for long.

He recounts, as if it were yesterday, how Leno and Rosemary LaBianca were tied up and dragged into separate rooms in their Los Feliz home, where they too died at the hands of Charles Manson’s brutal “family.”

“When Rosemary heard Leno getting stabbed, she cried out,” Kay says. He leans forward, hands splayed on knees, his voice rising like a terrified woman’s. “ ‘Leno! Leno!’ ”

Kay is slender, avid and 76. His white hair fluffs out above his tanned face. He helped put Manson family members behind bars for the 1969 slayings of nine people and has since attended 60 parole hearings to make sure they stayed there. He still recalls every awful detail of the murders, at times closing his eyes as if to block the images.

The slaughter and its aftermath “left the biggest imprint on Los Angeles, [on] all of Southern California,” Kay says. And also, it seems, on the prosecutor himself. “It’s the case that just never goes away.”

The Tate-LaBianca murders rocked California, drew international attention and came to symbolize the city of Los Angeles. And they continue to fascinate to this day, as their 50th anniversary nears.

“Helter Skelter” tours that follow the family’s bloody footsteps regularly sell out. Quentin Tarantino’s “Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood” — fiction wound around Manson family fact — opened Thursday night. Chief prosecutor Vincent T. Bugliosi’s 1974 book, “Helter Skelter,” has never gone out of print; it is joined on a regular basis by new entries into the Manson canon, at least two this summer alone.

Other killers have come and gone. Other crimes since have accounted for more deaths. People more famous than Tate, hairdresser-to-the-stars Jay Sebring and coffee heiress Abigail Folger have been slain. Still, the memory of Manson and the men and women he persuaded his followers to murder has not faded.

The question, which persists to this day, is why?

“It’s a story that still baffles,” says Linda Deutsch, who covered the Manson case for the Associated Press. “Manson had a streak of pure evil…. It persists now that he’s dead — finally. It’s as if the curse has not disappeared; it hangs over everyone who was ever involved with him.”

L.A. in the 1960s

Pamela Des Barres’ San Fernando Valley home is a shrine to the 1950s and ’60s — to rock ’n’ roll, spiritual quests and her life as a proud and prolific groupie. An oil painting of Walt Whitman (“my God,” she calls him) shares wall space with a portrait of Elvis. There’s a picture of James Dean, all leather jacket and motorcycle, on the hearth behind a bust of Jesus.

“Sixty-nine was my year,” says the author of “I’m With the Band” and member of the GTOs (Girls Together Outrageously). “That’s when the GTOs’ album came out. I was dating Mick Jagger, Jimmy Page, Waylon Jennings.… It was like anything could happen, and it was all good.”

The “greatest music was being made” in Los Angeles, says the onetime flower child from Reseda, who sports blond braids and an off-the-shoulder peasant blouse that shows off her tattoos — Elvis’ signature snuggling up against Jesus’ face. She is 70. “Pre-Altamont and pre-Manson, it really felt like the most magical place to live.”

That was before the Tate-LaBianca murders began grabbing headlines that August. Before a member of the Hells Angels stabbed a man to death at a free concert headlined by the Rolling Stones at the Altamont Speedway in Northern California in December. Before everything changed.

Los Angeles in the late 1960s was a place where someone like Manson could share a table at the Whisky a Go Go with someone like record producer Terry Melcher, Doris Day’s son. Where members of the Beach Boys could hang with members of the “family,” who, in turn, rubbed shoulders with the Straight Satans biker gang. Where beautiful people could throw parties and have no idea who was taking LSD by the pool. Where everyone was looking for a guru, no background checks required.

Hollywood gossip queen Rona Barrett says the entertainment industry and those in its orbit operated under “a caste system” — until they didn’t. In the late ’60s, the change was swift and equalizing.

That’s when Manson showed up.

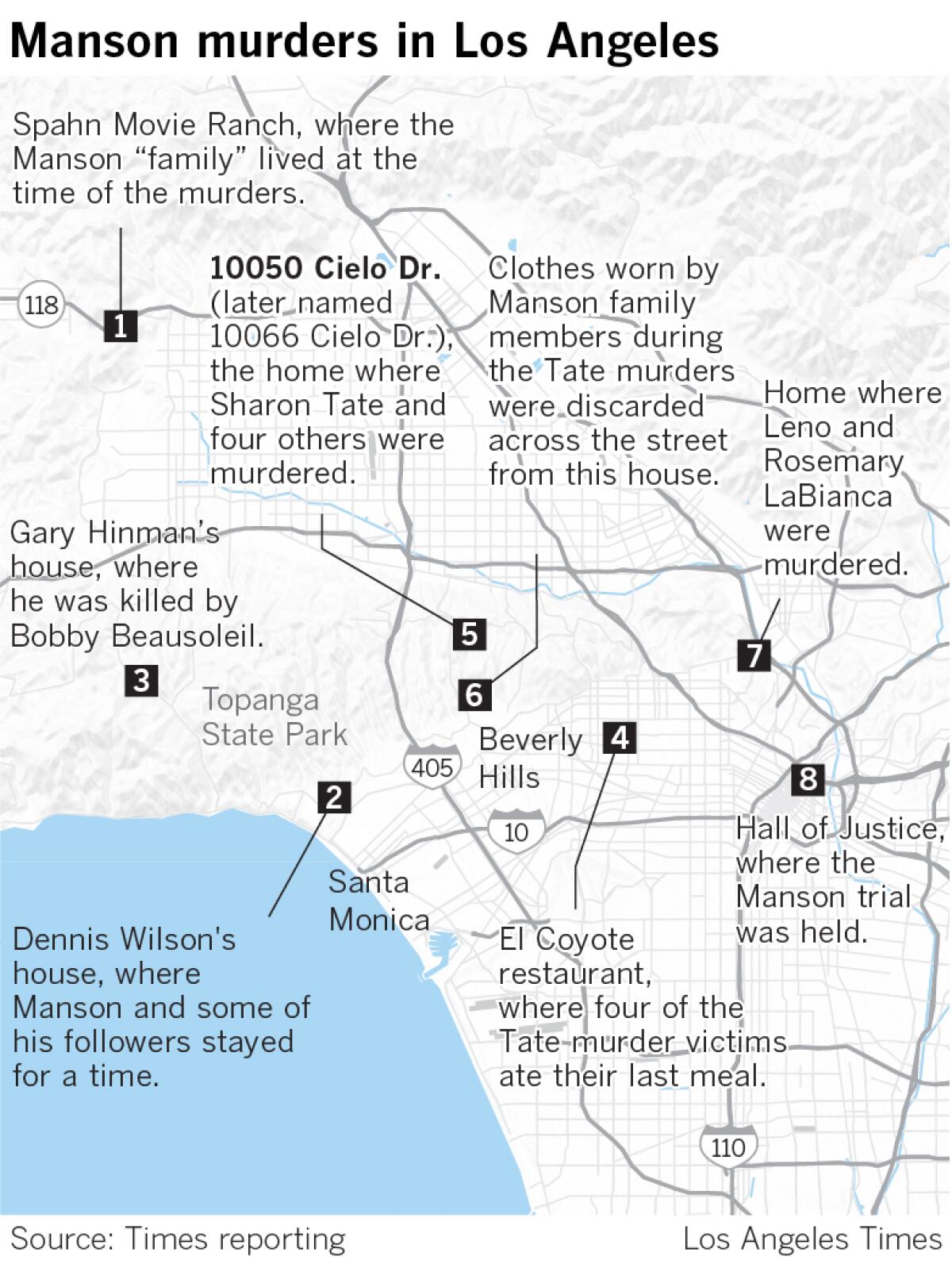

Charles Manson and his “family” committed heinous crimes across Los Angeles in 1969. Here is a timeline of what led up to the murders and the aftermath.

Designs on musical fame

Charles Milles Maddox, who would later take his stepfather’s last name, was born in 1934 to a desperately poor single mother in Ohio who cycled in and out of prison. She dragged her son around the Midwest and sent him off to reform school because he was out of control and her new husband didn’t like him. He was 12 years old and would go on to spend most of his life in one institution or another.

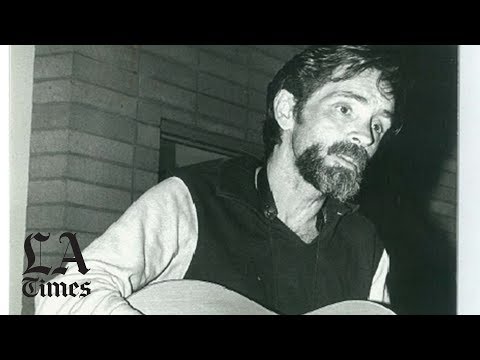

Prison was where Manson learned to play guitar. He was obsessed with the Beatles and their emerging fame, which prompted him to try songwriting so he too could become an international star. Prison was also where he learned the art of pimping and where he took a four-month Dale Carnegie course, with “How to Win Friends and Influence People” as required reading.

And it was where he met a fellow prisoner named Phil Kaufman, who had contacts in Hollywood. Kaufman told the aspiring musician that, when he was released from federal prison on Terminal Island, he should polish up some songs and go play for a guy he knew at Universal Studios.

That meeting, in late 1967, did not go well, but Manson was not deterred.

Soon he was seeking a musical sponsor to help him get a recording contract. The “girls” of Manson’s family were deputized to aid in the search, scouring the Sunset Strip and Topanga Canyon. They came through with Beach Boy Dennis Wilson, who picked a pair of them up while hitchhiking.

Wilson introduced Manson to his songwriting partner Gregg Jakobson and Melcher, who lived for a time with girlfriend Candice Bergen at 10050 Cielo Drive in Benedict Canyon, a house that was later rented to a prominent movie director and his actress wife.

It helped that Manson had a certain strange charm and at least a little musical talent. Jakobson says he could strum his guitar and make up a song on the spot about the flies that happened to land on his arm. He could talk for hours about his odd philosophies. And he had drugs and girls to spare.

Manson saw Wilson, Jakobson and Melcher as his tickets to fame and fortune. He auditioned for Melcher. He made several demos. The Beach Boys recorded his song “Cease to Exist,” but they changed the title and the words and didn’t give him a writing credit. Melcher eventually told Manson, “I don’t know what to do with you in the studio.”

Manson did not respond well. He had told the family that a contract was imminent. His future and his pride were riding on it.

Morbid curiosity

The voices are spectral and chilling, broadcast from speakers inside the white van with the black funeral wreath on its grille. On a recent summer morning, Scott Michaels, founder of Hollywood-based Dearly Departed Tours, prepares his passengers as he heads toward Cielo Drive in Benedict Canyon.

“This is the story of the Tate murders told by the killers.”

But it is still unsettling to hear the disembodied voices of Charles “Tex” Watson, Linda Kasabian, Patricia Krenwinkel and Susan Atkins describe that awful night 50 years ago — Aug. 9, 1969. They were Manson family stalwarts, 20 to 23 years old at the time. The recordings were taken from parole hearings and old media interviews.

Watson, with a slight twang, describing Manson’s instructions: “ ‘I want you all to go together and go up to Terry Melcher’s old house. And I want you to kill everyone in there.’ Terry Melcher was Doris Day’s son. And we had previously met him and had been in that house before.”

Kasabian: “I was told to get a change of clothing and a knife and my driver’s license.”

Atkins, sounding like a breathy little girl: “We drove to the house with instructions to kill everyone in the house, and not just that, but we were instructed to go all the way down, every house, hit every street and kill all the people.”

Michaels has christened this the Helter Skelter Tour, which takes the curious around various Manson family landmarks — minus the Spahn Movie Ranch and Death Valley, where the family lived at various times — and regularly sells out, even now, 50 years after the murders.

It’s four hours long, costs $85 a head and touches on each victim killed in the summer of 1969: Steven Parent, 18, who was visiting a resident of the guesthouse on the grounds of the Cielo Drive estate that Tate and her husband, Roman Polanski, had rented after Melcher moved out; Folger; her boyfriend, Voytek Frykowski; Sebring; Tate; the LaBiancas; Donald “Shorty” Shea; and Gary Hinman.

Michaels cues up the killers again, talking about the Tate murders.

Atkins: “The people in the house were all bound. And Voytek Frykowski, I believe was his name, I tied his hands with a towel. And I was instructed to kill him.”

Kasabian: “I was told to stay there and just kind of wait. Listen for sounds. And I did that. And then I started hearing, like, just horrible screaming. So I started running toward the house.... And that’s when I saw Voytek Frykowski being murdered, slaughtered, knifed.”

Krenwinkel: “Abigail Folger started to get herself undone. She took off. At that point in time, I left and followed her.… We went out a back door. And I ran her down. And I began to stab her.... I remember her saying, ‘I’m already dead.’ ”

One night later, Manson’s recruits stabbed the LaBiancas to death and mutilated their corpses.

“Up until this time, we all knew what the bad guys looked like,” Michaels says. “They wore black and they hid out in shadows, and they had shady expressions. They were predictable. Now these murderers were kids, and these kids became known as the Manson family.”

Angelenos on edge

In the aftermath of the slayings, Hollywood and environs went on lockdown. Four months would pass between the grisly deaths and Manson’s indictment on murder charges. In that empty space, headlines screamed and fear blossomed.

“Ritualistic murders.” “EXTRA — SECOND RITUAL KILLINGS HERE.” “Drugs Found Near Tate Murder Site, Pills, Marijuana Located in Slain Hair Stylist’s Car Outside Estate.” “Police Seek Link in New Killings.”

Barrett, whose job it was to chronicle the lives of the rich and famous, says, “Everyone went crazy for a moment.” Everyone was frightened, no one wanted to go out, and everyone wanted protection. Gun sales jumped. There was a run on security services and guard dogs.

“I think it changed everyone’s feelings about protecting themselves, and especially those who had important names and had made some success,” says Barrett, who is now 82.

Kay was a district attorney in Los Angeles County for 37 years and nine months. Only twice during that long career, he says, has he seen people “so frightened in L.A. First with the Manson case, and the second one was with the Night Stalker.”

Barrett felt that fear firsthand. She lived not far from Tate and considered the beautiful young actress a friend. The morning after the murders, she got a phone tip, raced over to the house on Cielo Drive and was the first journalist on the scene.

On that morning, she saw Parent slumped over the wheel of his car, bodies covered in blankets on the lawn. Not long after, rumors swirled about a hit list. Her broadcast company hired a private guard for her. An editor friend who worked on Barrett’s movie magazines came to stay with her.

“In the middle of the night, there was a gunshot sound,” Barrett recalls. The guard had been hit. “I never knew what the final outcome was. But he was taken away, and the next thing I knew is, I had three major police people come to my house, set up big guns, everything. I mean, it was like a scene from a movie.”

There were also death threats, she says. They were “short little letters.” They said, “you are next.”

“I’ll never be able to say that the threats were really linked to the Sharon Tate murder,” Barrett says. “But I can’t say that they were not.”

An era on trial

Manson was formally charged with seven counts of murder Dec. 9, 1969, while in police custody in Inyo County. The big break in the case had come a month earlier when Atkins, who was being held on other charges, bragged to her cellmates at Sybil Brand Institute for Women about her involvement in the slayings.

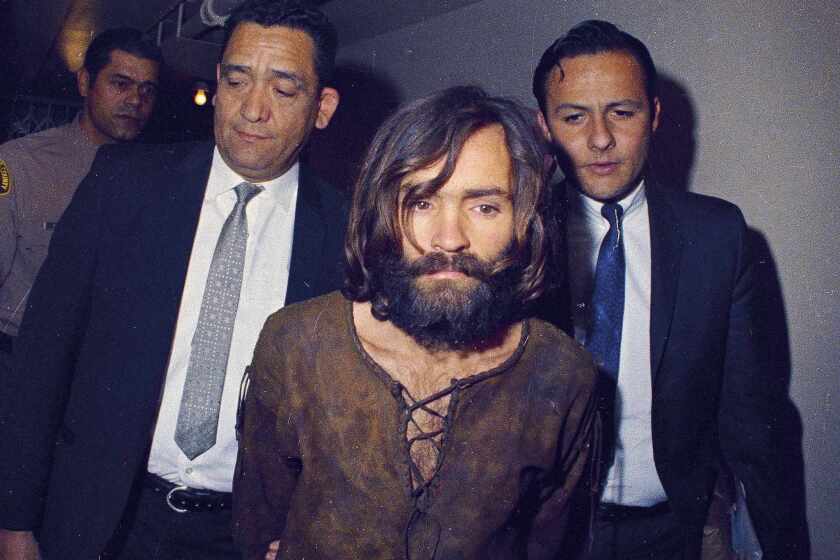

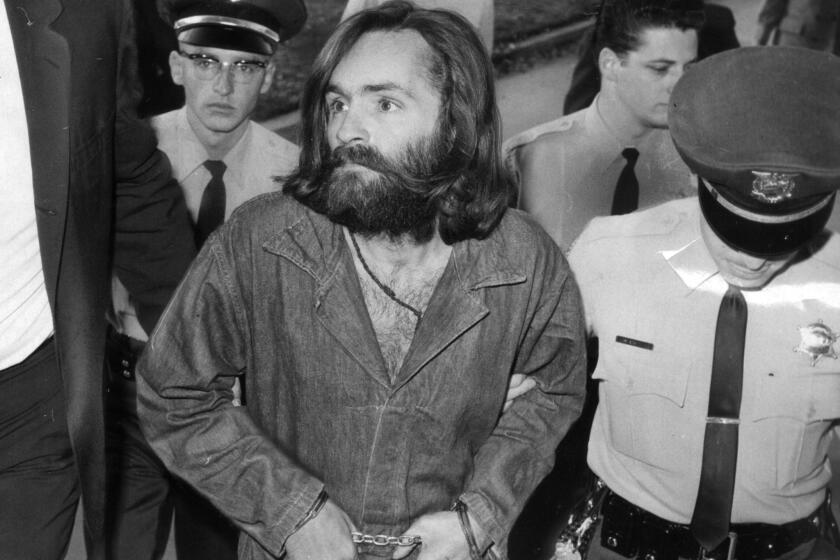

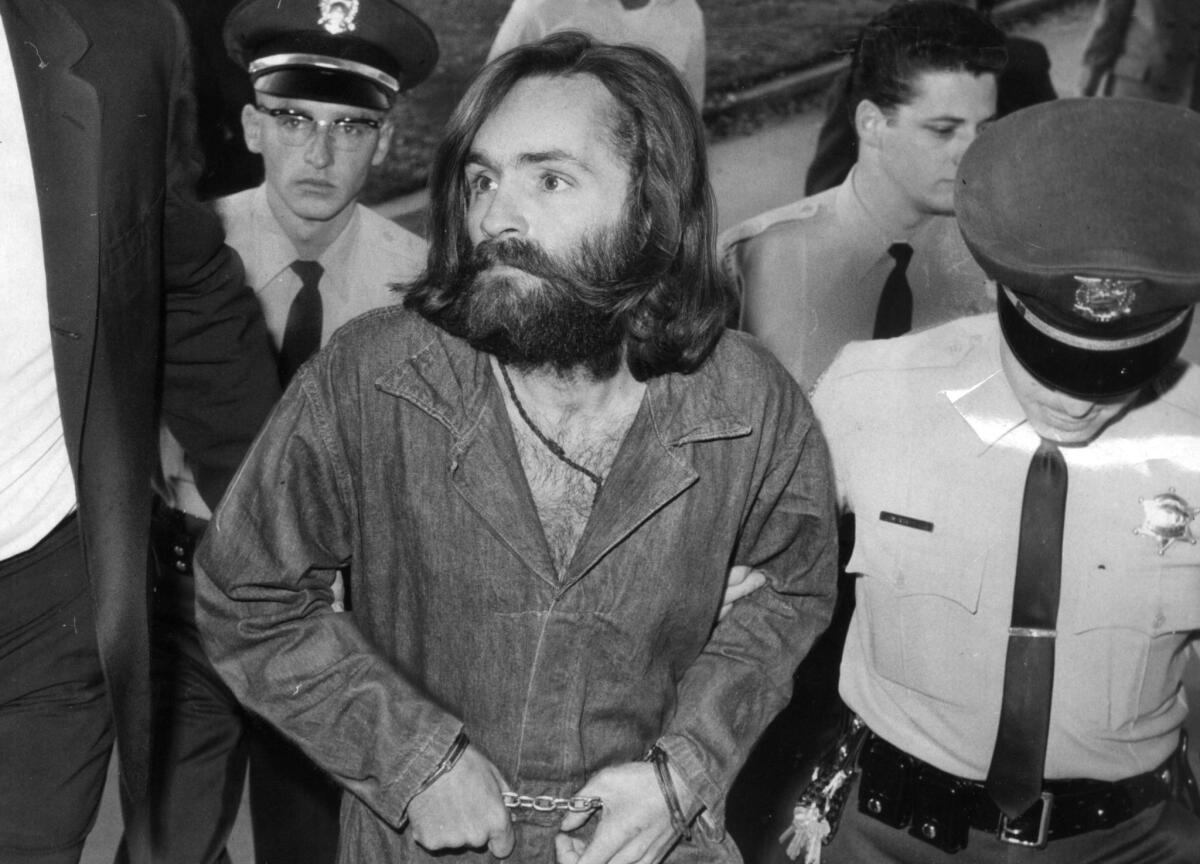

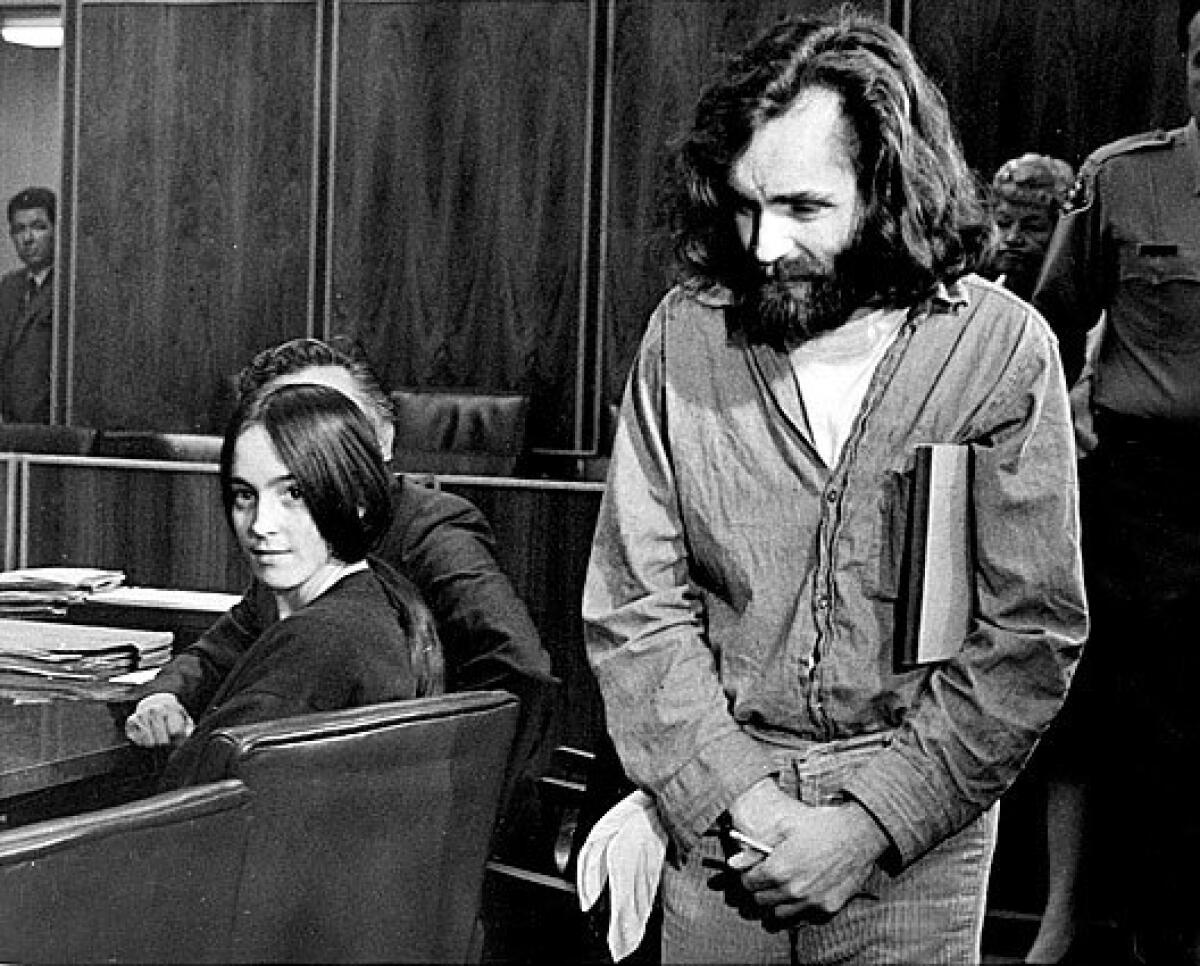

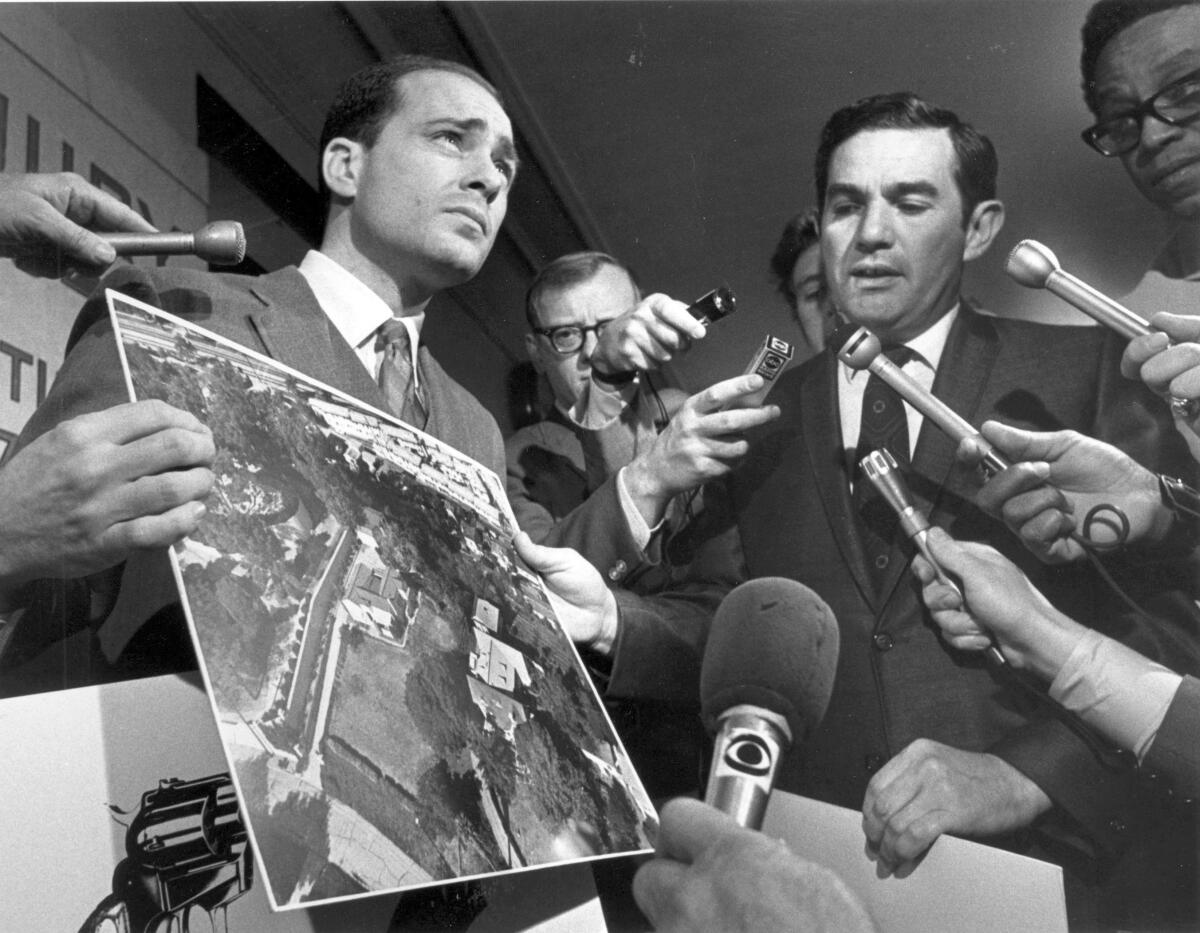

Deutsch was at the Hall of Justice in downtown Los Angeles when Manson arrived that same day, a tiny figure in buckskin, hair in scraggly disarray. The hall outside the courtroom was jammed with camera crews, packed so tight it was hard to move.

They spotted Manson, surged forward, knocked a drinking fountain off the wall. Water flooded the corridor. Deutsch turned to her friend Sandi Gibbons, who covered the Manson case for City News Service.

“And I said, ‘This is crazy,’ ” Deutsch recounts. “And I didn’t know how crazy it was going to be for the entire trial.”

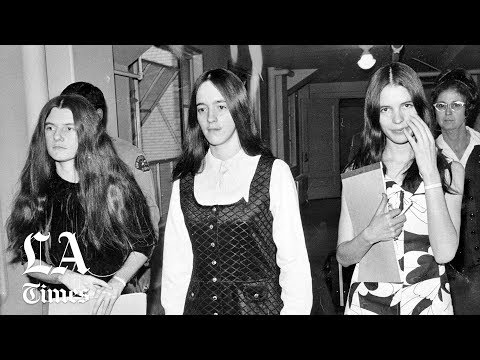

Gibbons still has a copy of Bugliosi’s opening statement in the trial of Manson, Atkins, Krenwinkel and Leslie Van Houten, 13 typewritten pages explaining that “one of Manson’s principal motives for the Tate-LaBianca murders was to ignite Helter Skelter.”

“In other words,” the chief prosecutor wrote, Manson wanted to “start the black-white revolution by making it look like the black people had murdered the five Tate victims and Mr. and Mrs. LaBianca, thereby causing the white community to turn against the black man and ultimately lead to a civil war between blacks and whites, a war Manson foresaw the black man winning.”

Manson had his own opener. He walked in that morning with an X gouged into his forehead. Supporters outside the courtroom distributed a lengthy declaration from the cult leader. Gibbons copied a single sentence of Manson’s statement onto the first page of Bugliosi’s opening remarks: “I have Xed myself from your world.”

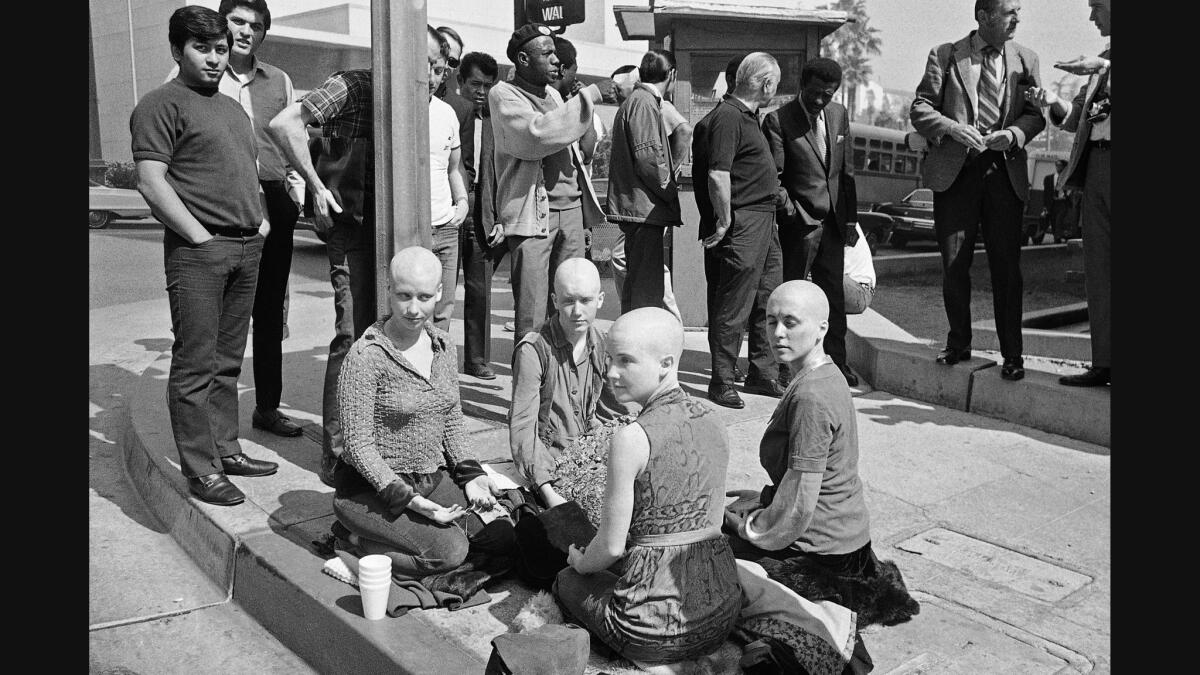

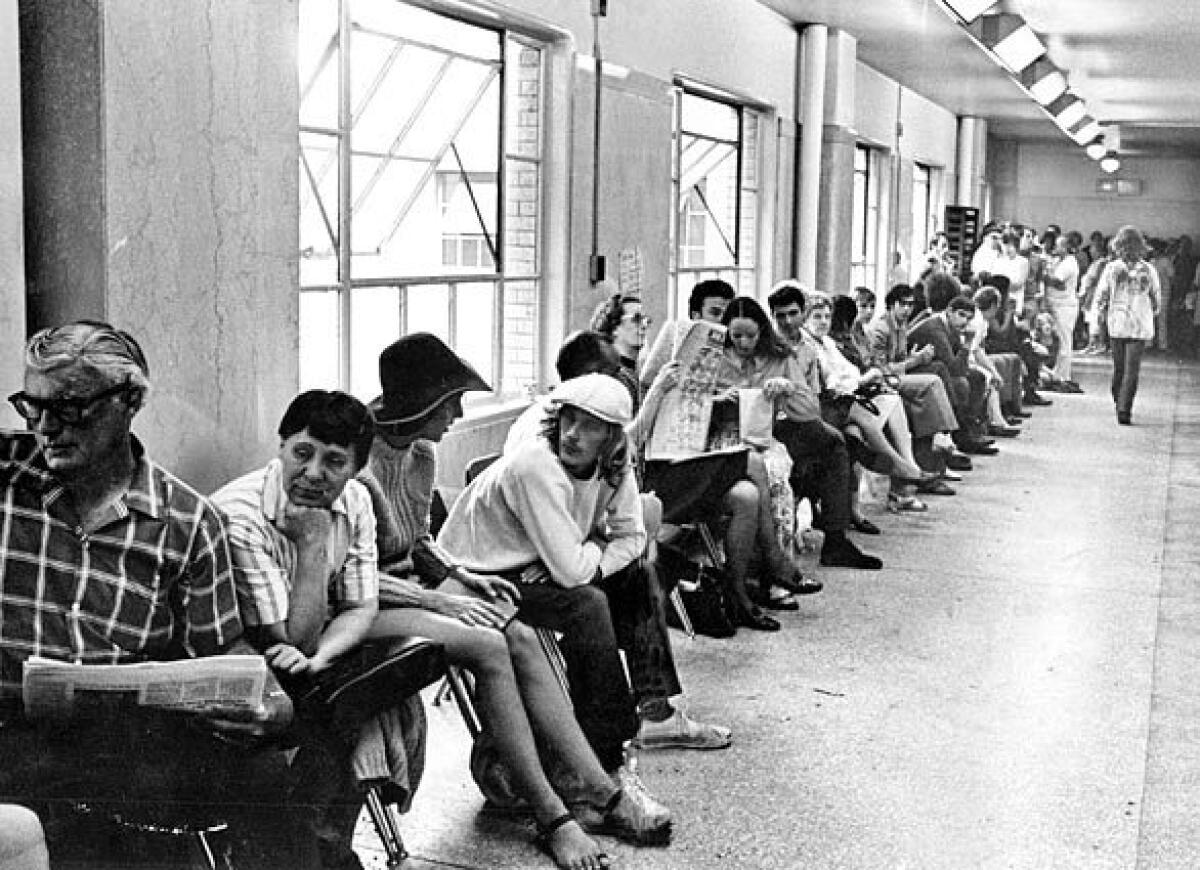

During the trial, some of Manson’s female followers camped outside the Hall of Justice, heads shaved, Xs carved into their own foreheads, selling Manson’s album “Lie: The Love and Terror Cult” for five bucks. Michelle Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas showed up, along with other celebrity friends of Tate and Polanski.

An artist calling herself the Whore of Babylon charged into the courtroom one day during the nine-month proceeding and announced that she had “come to save my brother Manson.” She was arrested. Actor Robert Conrad, set to play a hard-nosed district attorney in a television drama, showed up to study Bugliosi in action.

“The ultimate was when Manson got upset,” Deutsch says, “and he propelled himself across the counsel table at the judge with a pencil in his hand, screaming, ‘Someone should cut your head off!’ ”

All four defendants were found guilty and sentenced to death. When the California Supreme Court abolished the death penalty in 1972, their sentences were commuted to life in prison. They have never been granted parole. Atkins died in 2009; Manson in 2017.

Deutsch and Gibbons, fast friends after their time covering Manson, get together regularly to reminisce. They have covered a long line of celebrity trials since: O.J. Simpson, Michael Jackson, Patty Hearst. They argue that the Manson drama holds a special place in California jurisprudence and left its mark on Los Angeles.

“It was the first big celebrity trial of modern Los Angeles,” says Deutsch, whose home office is filled with grim memorabilia. “It was a trial that put the era on trial, the entire ’60s culture.”

The killings, the trial, the court proceedings, she says, “began to give Los Angeles a reputation as a place where violence could happen, senseless violence. There had never been killings like this before, where people were butchered for no reason.”

Says Gibbons, “It was indeed the weirdest trial that I’ve ever covered.”

The death of the ’60s?

Five decades later, the Manson murders continue to hold sway in Southern California, prompting competing theories as to why.

The crimes did not single-handedly end the 1960s, no matter what Joan Didion says in “The White Album,” her seminal book of essays published in 1979. (“Many people I know in Los Angeles believe that the Sixties ended abruptly on August 9, 1969,” Didion wrote.)

Yes, Manson, with his family doing the heavy lifting, was responsible for nine grisly deaths — the Tate-LaBianca victims, stuntman Shea and musician Hinman, a friend but not a full-fledged family member.

But the cult leader had ample help putting a bayonet — his weapon of choice — through the heart of a much more innocent time. Depending on who you ask, his accomplice was Altamont, LSD or the May 4, 1970, massacre of unarmed college students by members of the Ohio National Guard at Kent State University.

Jonathan Taplin, emeritus director of the Annenberg Innovation Lab at USC, fingers Altamont as Manson’s chief accessory in killing the 1960s. In 1969, Taplin was tour manager for Bob Dylan and the Band.

The Tate-LaBianca murders happened about a week before Woodstock, but they barely dented the euphoria of the music festival at a muddy dairy farm 2,800 miles away in rural New York, Taplin says. “It was just a killing, you know, a robbery or whatever,” he recalls. Then, on Dec. 6, Altamont happened. Three days later, Manson was charged with murder.

“And then it was over,” Taplin says. “All that optimism was just deflated and drained out. And then, obviously things got worse. Kent State.… All of a sudden we saw this dark side of this thing that was so light.”

Jeff McDonald, co-founder of the alt-rock band Redd Kross, also doesn’t buy it. McDonald was just turning 6 when the murders happened, grew up seeing Bugliosi’s “Helter Skelter” on every parent’s coffee table. If Manson and the family killed anything, McDonald argues, it’s the 1950s.

Followers of Charles Manson were tied to the deaths of nine people in the summer of 1969.

“The postwar people had this idea of their newfound middle class, and especially white middle class,” says guitarist McDonald, who included a cover of Manson’s song “Cease to Exist” on the group’s 1982 debut album “Born Innocent.” But then, their kids were “radicalized” and some “did these horrible things.”

“It just destroyed that dream,” he said.

To McDonald, “Manson was kind of like an act of rebellion. There was never any kind of worship of the philosophy of Charles Manson.… It was like the second phase of punk rock for us.”

Manson’s impact is not the only thing that continues to be debated. As the years pass, books publish and movies come out, the facts of the case have become a little hazier.

Gibbons eventually left City News Service for the Los Angeles Daily News. She joined the district attorney’s office in 1989 as public information officer. Now, 50 years after the murders, she says she does not believe Bugliosi’s theory of the case, that Manson heard instructions to start a race war in the lyrics of the Beatles’ “White Album.”

Her view? That Manson sent his minions out to “put the fear of death into Terry Melcher.” And that he wanted to create a copycat murder to confuse authorities about who may have killed Hinman and, therefore, free family member Bobby Beausoleil, who was eventually convicted of the murder.

She is not the only doubter of the official story line. Nikolas Schreck, a Berlin-based musician, author and filmmaker, is one of the many Manson contrarians. He described Manson as a “talented, poetic musician with wisdom and with a strong, powerful philosophy who got caught up in these tragic crimes. But he was not the sole instigator and responsible for the crimes.”

Schreck made the film “Charles Manson Superstar” in 1989 and will screen the movie at Zebulon near Silver Lake on Aug. 10. It is one of many Manson-related events in the works.

By the time the next big Manson anniversary rolls around — the 75th in 2044 — most of those directly touched by the murders will be gone. The big question is whether Manson will have legs or fade away, just another criminal in a world full of them.

The cult leader had his own answer, compliments of a lengthy interview in Schreck’s movie.

“I’m gonna survive,” he said. “If you do or not, that’s up to you.

“You dig?”

Read our full coverage of the Manson murders.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.