Column: Silicon Valley elites are afraid. History says they should be

It’s become a common refrain among a certain set of Silicon Valley elite: They’ve been treated so unfairly. Case in point: Even after their bank of choice collapsed spectacularly — in no small part of their own doing — and the federal government moved with dispatch to guarantee all its deposits, tech execs and investors nonetheless spent the subsequent days loudly playing the victim.

The prominent venture capitalist David Sacks, who had lobbied particularly hard for government intervention, bemoaned a “hateful media that will make me be whatever they need me to be in order to keep their attack machine going.” Michael Solana, a vice president at Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund, wrote on his blog that “tech is now universally hated,” warned of an incoming “political war,” and claimed “a lot of people ... genuinely seem to want a good old fashioned mass murder,” presumably of tech execs.

It was a particularly galling display, a new high for a trend that’s been on the rise for some time. Amid congressional hearings and dipping stock valuations, the tech elite have bemoaned the so-called techlash against their industry by those who worry it’s grown too large and unaccountable. Waving away legitimate questions about the industry’s labor inequities, climate impacts and civil rights abuses, they claim that the press is biased against them and that they’re besieged on all sides by “woke” critics.

If only they realized just how good they have it, historically speaking.

It was mere decades ago, after all, that the Silicon Valley elite faced the active threat of actual, non-metaphorical violence. The most adamant critics of Big Tech of the 1970s didn’t write strongly worded columns chastising them in newspapers or blast their politics on social media — they physically occupied their computer labs, destroyed their capital equipment, and even bombed their homes.

“Techlash is what Silicon Valley’s ownership class calls it when people don’t buy their stock,” author Malcolm Harris tells me. “Today’s tech billionaires are lucky people are making fun of them on the internet instead of firebombing their houses — that’s what happened to Bill Hewlett back in the day.”

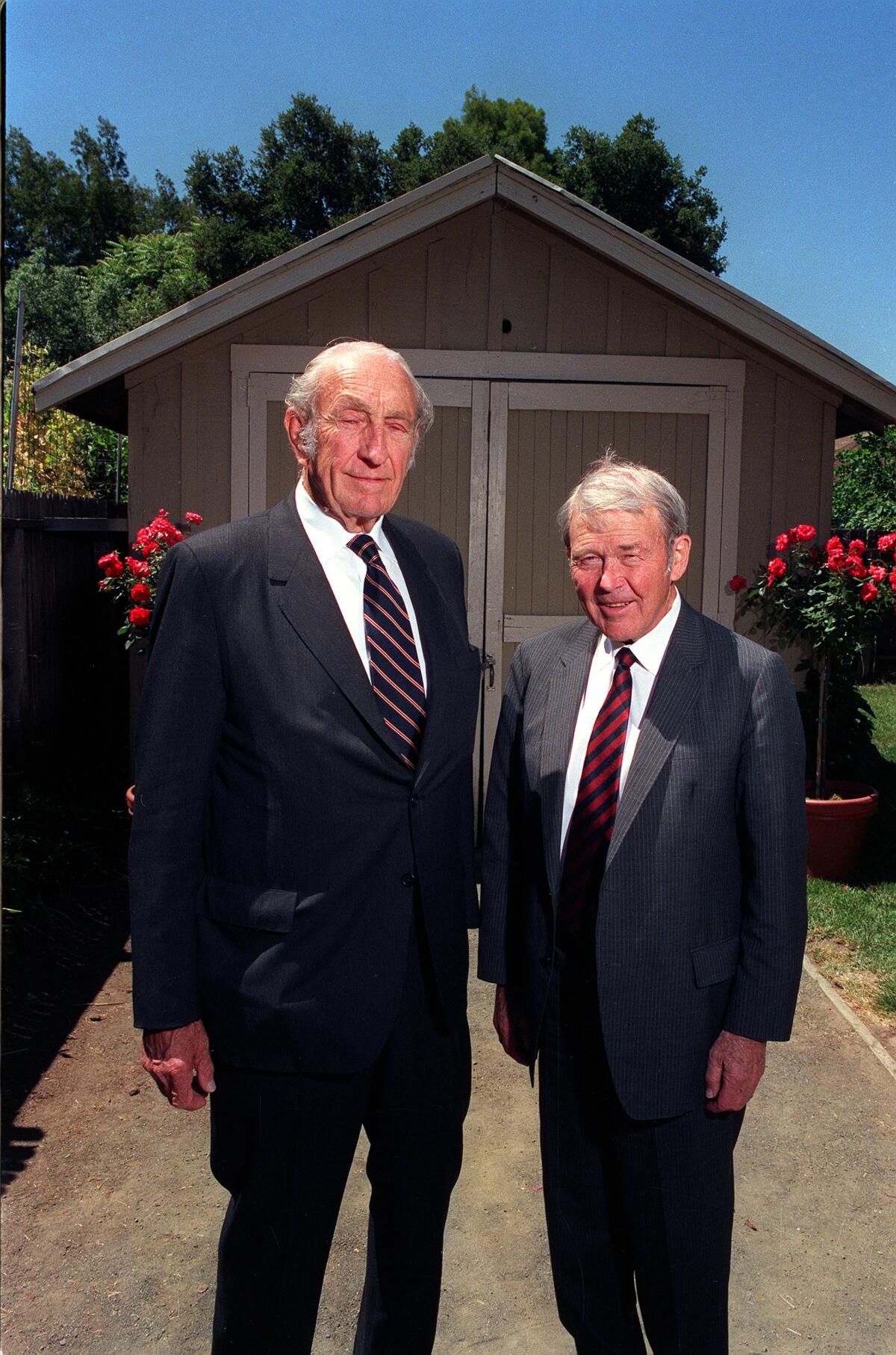

A 1987 article in this newspaper makes his point. When William Hewlett retired from the company he founded, Hewlett-Packard, or HP, as it’s known today, The Times dedicated a full paragraph to the various threats of violence that the billionaire faced in the 1970s:

“In 1971, radical animosities directed at the upscale Palo Alto community and Stanford University campus brought terror into the Hewletts’ lives: The modest Hewlett family home was fire-bombed. In 1976, son James, then 28, fought off would-be kidnapers. The same year, a radical group called the Red Guerrilla Family claimed responsibility when a bomb exploded in an HP building.”

Harris is the author of “Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World,” the book that is currently the talk of the town — it just hit the L.A. Times bestseller list — though not for the reasons that the valley’s elites might prefer. It’s a robust, sprawling history that’s intensely critical of the Great Men of tech history, and even more so of the systems they served. It’s been received enthusiastically, as an overdue corrective to the industry’s potent penchant for self-mythology.

Malcolm Harris, author and firebrand leftist critic, on returning to his roots in ‘Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism and the World.’

And some of the most potent mythologies, of course, rely on omission. Take, for instance, the popular narrative that whiz kids such as Hewlett and Steve Jobs started the computer revolutions from their garages in Palo Alto, where their starkest opposition came in the form of square old corporations such as IBM and Xerox — and not actual, bomb-throwing revolutionaries.

Harris’ work reminds us that this was far from the case. There was a movement far more organized, far more militant, and far more sharply opposed to the Big Tech companies of the day than anything we’ve seen in the last 10 years.

When we think of the 1960s in California, we think of disparate, panoramic happenings in an explosive decade; the war in Vietnam, the rise of the computer, the student protest movement, and so on. But Harris argues that the computer revolution didn’t simply coexist with the war — it fueled it.

“These developments weren’t just connected,” Harris writes, “they were the same thing.”

Intel and Hewlett-Packard revolutionized microchips, alright, but they sold them to the U.S. military, which used them to guide the weapons of war it was deploying in Southeast Asia. To the students, activists and organizers of the so-called New Left, Silicon Valley was hard-wiring the war effort. It was an instrument of oppression, and it had blood on its hands.

All this set the stage for a revolt against Silicon Valley’s core operators. Palo Alto radicals “singled out Stanford’s industrial community and its role in the Vietnam War specifically and capitalist imperialism generally,” Harris writes. “And once they got their collective finger pointed in the right place, they attacked.”

That’s not a figure of speech either. They really, quite physically, attacked the people and infrastructure of Silicon Valley that were connected to the war effort.

“The New Left tried to blow up more or less every computer they could get their hands on,” Harris says. “And since both were likely to be found on college campuses, they got their hands on a bunch of them.” (At the time, remember, there was no PC — computers were still room-sized machines.)

The failure of Silicon Valley Bank demonstrates the risk in showering unproven companies with cash and in handing so much power to venture capitalists to manage the process.

The reasoning was simple: These computers were making the war possible, both by providing the physical hardware for missile targeting systems and such, and by processing data used to plan combat missions. The war caused untold suffering and death; dismantle the war machine, hamper the war effort. So that’s exactly what members of Stanford’s leftist organizers, affiliated with groups such as Students for a Democratic Society, or SDS, tried to do.

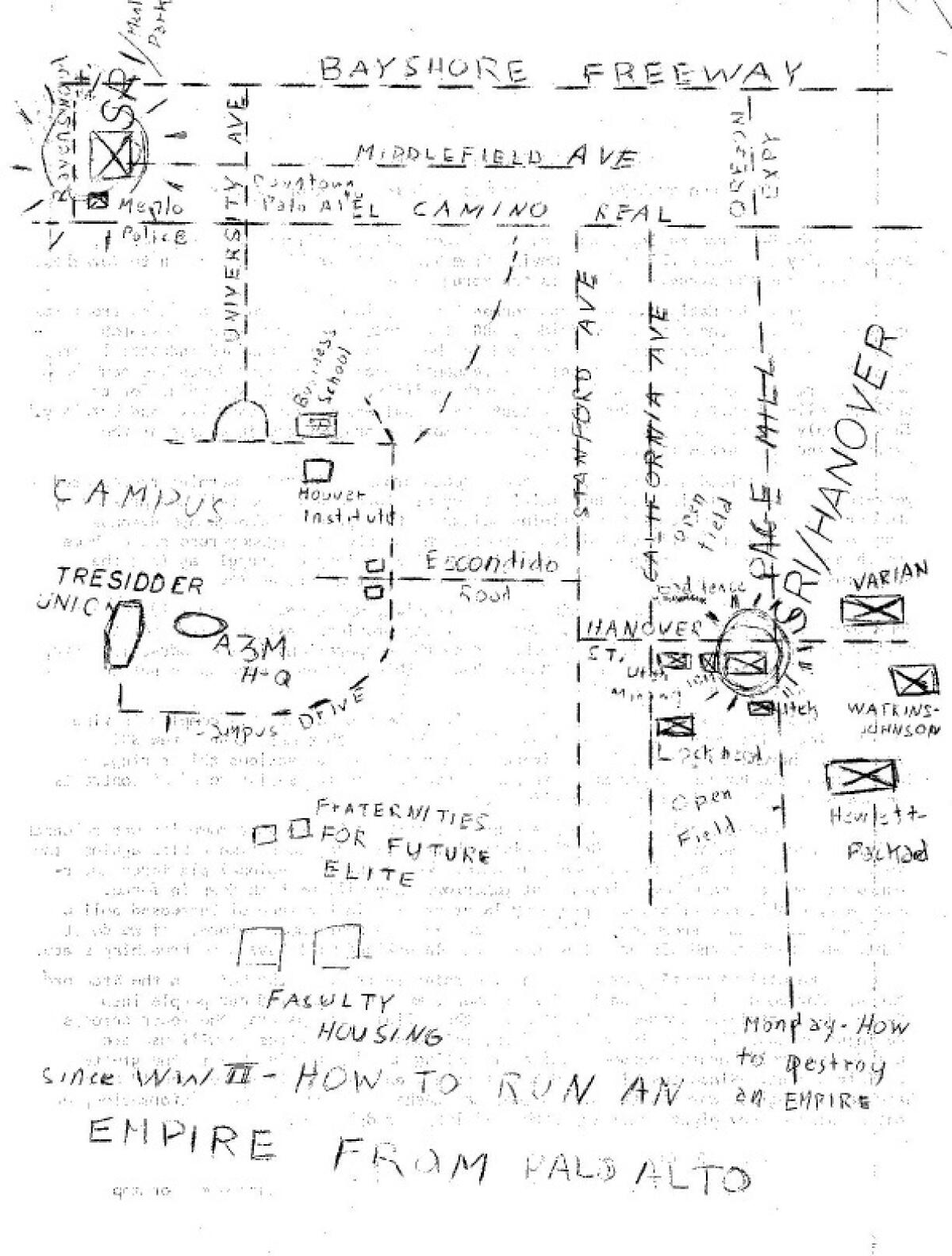

First, they attempted peaceful tactics, such as a pressure campaign to halt the manufacture of napalm. It didn’t work. So, taking their cues from the Black Panther Party, which was at the time perhaps the most powerful and influential radical left group in the nation, Stanford students — and even faculty — adopted direct and militant tactics. They published maps of the high-profile tech companies and research offices in Palo Alto that had won defense contracts or were otherwise involved in the war effort.

After the U.S. military bombed Cambodia, the student left escalated its tactics by targeting the very data processing infrastructure that was aiding the war effort.

They occupied the Applied Electronics Laboratory in Stanford. The AEL was an on-campus lab that was carrying out classified research for the war effort for the Pentagon, and students moved to shut it down. The occupation ended with a major concession: that classified military research no longer would be conducted on campus, and that its resources would be used instead for community purposes.

The victory helped inspire copycat actions across the country — and even more militant ones. Students and activists bombed or destroyed with acid computer labs at Boston University, Loyola University, Fresno State, the University of Kansas and the University of Wisconsin, among others, causing millions of dollars in damage. The explosion at the University of Wisconsin-Madison killed Robert Fassnacht, a postdoctoral researcher who, unbeknownst to the saboteurs, had been working late at night. IBM offices in San Jose and New York were bombed too.

With momentum at their backs, Stanford radicals decided to up the stakes and to occupy an even larger target: the Stanford Research Institute, or SRI, an off-campus research center that was overseen by the university’s board of trustees and that had won enormous military contracts.

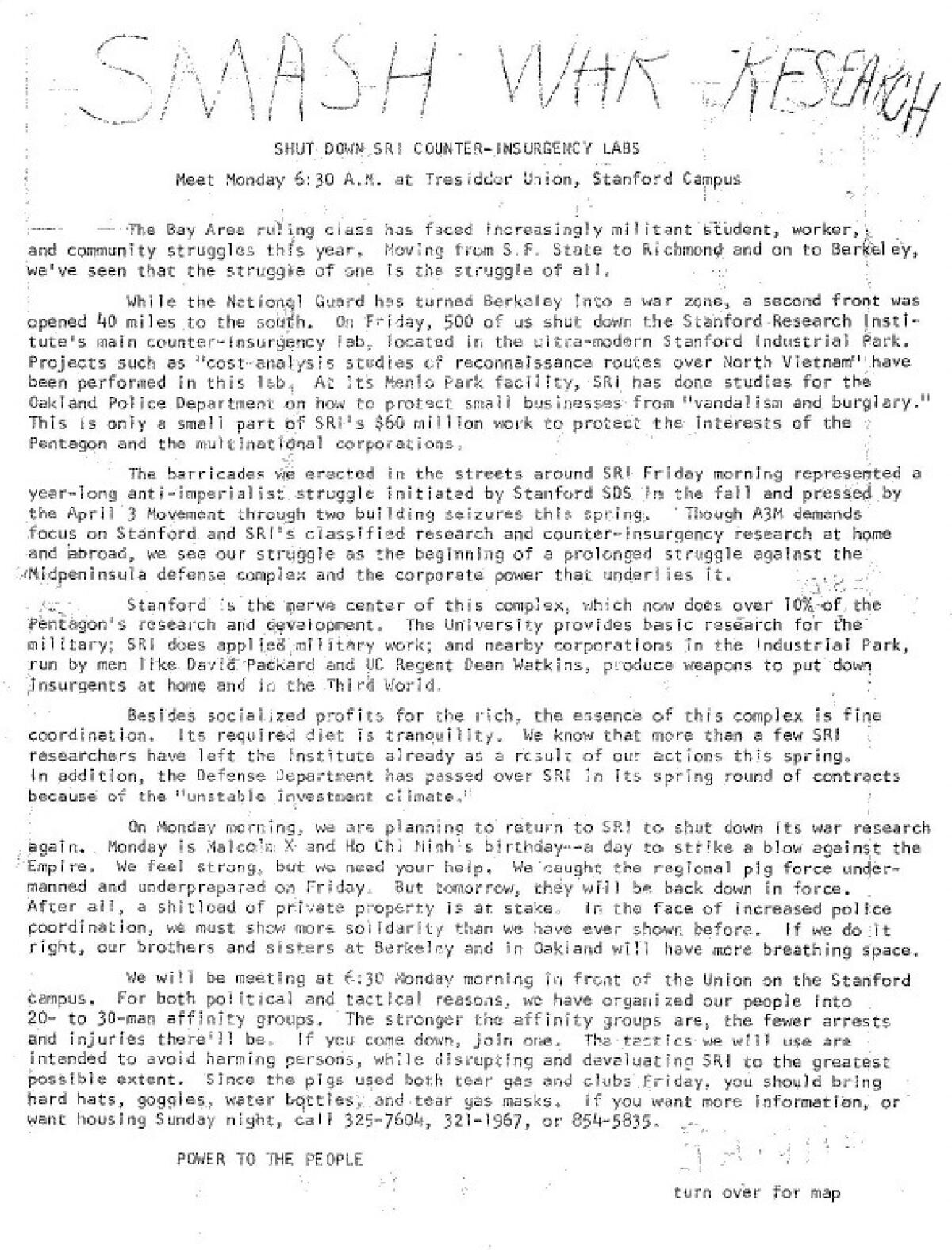

“Stanford is the nerve center of this complex, which now does over 10% of the Pentagon’s research and development,” activists wrote in a flier promoting the action. It lambasted the “socialized profits for the rich” generated by the SRI, and how it was used to “produce weapons to put down insurgents at home and in the Third World.”

This flier had a map too, with the pertinent Big Tech buildings circled; Hewlett-Packard, Varian, SRI. It was labeled “How to Destroy an Empire.”

It was a militant movement, and it was effective. It deterred investment in the war effort, made universities rethink their involvement with the Department of Defense, and contributed to the eventual withdrawal and policy reforms won by the broader antiwar movement.

So why don’t we remember it much? Why do we remember the summer of love and communitarian counterculture and the Whole Earth Catalog — but not a violent struggle over the deployment of technology and those who profited from it?

Or as Harris puts it: “Why are we more likely to hear about the Yippies trying to levitate the Pentagon than SDS successfully bombing the Pentagon?”

One reason is pretty simple: It’s a feel-bad story that complicates the narrative that has grown increasingly central to how we understand the history of how our technology was invented and produced.

“In Silicon Valley in particular, the clear anti-tech strategy of the anti-war movement is inconvenient for the predominant ‘hippies invented the Internet’ narrative,” Harris says, “so many of the region’s historians have shunted that part aside.”

But the fear remains. Even if there’s been nothing resembling organized threats on their well-being — guillotine memes on Twitter don’t count — today’s tech elites can certainly feel the resentment brewing.

Maybe that’s why they’re so sensitive to the suggestion that the government rescue of SVB was a “venture capitalist bailout” — that it was more special treatment for a constituency that drives Model Xs to their Tahoe ski chalets, that wants to reap the rewards of investing in world-changing technologies while bearing so little of the actual risk. Much of today’s most visible tech set knows that lots of people don’t like the inequality they represent, the preferential treatment they seem to enjoy, and the forces their companies and investments have set in motion.

They surely see Amazon workers and Uber drivers becoming increasingly agitated and organized, and openly pushing for change against gross inequalities. They see movements for gender equality and climate justice at Google and Microsoft.

They see the outrage over the fact that, like its forebears in Hewlett-Packard and earlier Silicon Valley companies, the newest iteration of Big Tech has become a major defense contractor too — Google, Amazon and Microsoft have vied to provide cloud, artificial intelligence and robotics to the military — and they see movements opposing it, as in the #TechWontBuildIt effort, where tech workers campaigned to reject such projects. (And hey, HP is still a defense contractor.) They see backlash against social media companies giving authoritarian regimes the tools to commit atrocities. If they knew to look, today’s tech elites might see a lot of the same kindling that was laid on the ground in the combustible ‘60s.

“They think about this stuff constantly, but it’s in the build-a-killer-robot-army way, not the Patagonia way,” Harris says, referring to the former Patagonia billionaire Yvon Chouinard, who gave away his entire company as a means of combating the ills of extreme wealth.

In other words, they’d rather keep up the flame wars on social media and build survival bunkers in Montana than address the social ills their critics charge them with exacerbating.

“I think they are very, very worried,” Harris says. If history is any precedent — perhaps they should be.