Amazon boosted junk ads, deleted messages to thwart antitrust probe, FTC says

Amazon.com doubled the number of junk ads to boost profits and deleted internal communications to thwart a federal antitrust investigation, according to fresh details released by the U.S. Federal Trade Commission in a less-redacted complaint against the online retail giant Thursday.

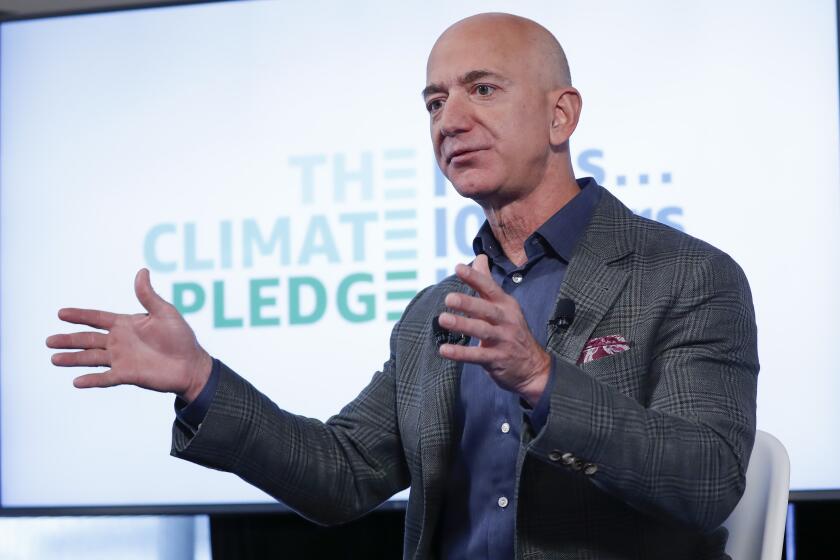

Amazon’s founder and former chief executive, Jeff Bezos, personally ordered executives to accept more ads, even ones the company had internally labeled as “defects,” indicating they weren’t relevant to user searches, according to the new version of the complaint.

The FTC alleges that Amazon’s increased use of ads boosts profits while it harms sellers and consumers, making it harder for shoppers to find the products they are searching for. “We’d be crazy not to” increase the number of advertisements shown to shoppers,” the FTC quoted Amazon executives as saying.

One executive compiled a number of the defective ads showing “buck urine” showing up in response to searches for “water bottles” or T-shirts for the Los Angeles Lakers basketball team in response to queries for the Seattle Seahawks football team merchandise.

In third quarter 2023 earnings announced last week, Amazon reported advertising revenue of $12.1 billion, making the company’s ad unit its fastest-growing business.

Amazon said its search results consider a number of factors and users can easily refine their results.

“Amazon works hard to make it fast and easy for customers to find the items they want and discover similar options by providing a mix of organic and sponsored search results,” Amazon spokesperson Tim Doyle said. He also cited a study by a London marketing firm that found consumers find Amazon ads relevant and useful.

The lawsuit by the Federal Trade Commission and 17 states shines a light on Amazon’s monopolistic actions that buyers and sellers know all about. But what’s the remedy?

‘Disappearing message’

The company also deleted internal communications using the “disappearing message” feature of Signal and destroyed more than two years’ worth of such communications, from June 2019 to at least early 2022, the FTC alleged.

Amazon denied that its employees deleted messages, saying the company informed the FTC about the Signal usage, “painstakingly collected Signal conversations from its employees’ phones, and allowed agency staff to inspect those conversations.” Some executives began to use the encrypted communications app after Bezos disclosed in 2019 that his phone had been hacked and alleged the National Enquirer tabloid sought to publish his intimate photos and texts.

The agency sued Amazon in September, accusing the e-commerce giant of monopolizing online marketplace services and stifling competition. The complaint alleges the company illegally forces sellers on its platform to use its logistics and delivery services in exchange for prominent placement and punishes merchants who offer lower prices on competing sites.

Amazon has said it will challenge the lawsuit in court, adding that it “radically” departs from the agency’s mission of protecting consumers and is “wrong on the facts and the law.”

The original complaint was heavily redacted, blacking out information about Amazon’s operations, including details about the company’s scale, its Prime subscriber base and a pricing algorithm called “Project Nessie” that the agency said foisted higher costs on shoppers, belying the company’s claim to prioritize the welfare of its customers.

Fees the company collects from third-party sellers have risen for six years in a row, squeezing their margins.

Over the ensuing weeks, the FTC and Amazon wrangled over what details could be publicly shared, with the company determined to protect information that could provide competitors insights into its e-commerce strategy and business metrics.

Seller Fulfilled Prime

According to the FTC’s new complaint, 98% of Amazon sales occur directly from the so-called “Buy Box” where the company selects one featured offer from among the sellers hawking a specific product.

The FTC alleges that Amazon has illegally tied use of its marketplace with its logistics service — Fulfillment by Amazon — where merchants pay to have Amazon take care of warehousing and shipping. Using the logistics service helps ensure a merchant’s products qualify for Amazon’s Prime subscription service and the featured offer in the “Buy Box.”

Amazon began offering a program called Seller Fulfilled Prime in 2015 that allowed merchants to qualify for the speedy shipping promise without using the company’s logistics service, the FTC alleged. At its peak, 15,000 sellers were using it, according to the FTC. Amazon worried internally that the program was “[s]trategically risky” and could damage the company’s own logistics service, the FTC alleged, with a senior executive saying he was “losing [his] mind” after United Parcel Service Inc. was advertising to merchants that it could fulfill orders.

In 2019, Amazon stopped accepting new merchants into the program.

“Amazon decided to prioritize excluding rivals and foreclosing competition, even if it came at a cost to Amazon’s customers,” the FTC alleged.

In a statement, Amazon said the FTC cited “misleading figures” and its original program didn’t meet “the high standards and expectations our customers have for Prime.”

‘Project Nessie’

The FTC alleged that Amazon created an algorithmic tool, nicknamed Project Nessie, that generated more than $1 billion in additional profits for the company by raising prices in its marketplace.

Amazon and many other online retailers use automated tools to match pricing to what competitors are charging. Realizing that many websites set their pricing tools to correspond with Amazon’s marketplace, the company created Nessie to raise prices on products that other retailers would match, the FTC alleged.

“The FTC claims that an old Amazon pricing algorithm called Nessie is an unfair method of competition that led to raised prices for consumers,” Amazon said in a statement responding to the new details in the less redacted complaint. “This grossly mischaracterizes this tool. Nessie was used to try to stop our price matching from resulting in unusual outcomes where prices became so low that they were unsustainable.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.