SOUTH DOS PALOS, Calif. — Robin Koda navigated the levees of her family’s rice farm with the grace of someone who has been moving among water, soil and grass her whole life.

She wore jean overalls and a wide-brimmed woven hat that offered minimal protection from the oppressive heat that rippled under a cloudless sky. It was July 14, and the almanac would later peg the high at 100 degrees. Somehow, it felt much hotter than that.

Still, it was something close to bearable near the water, whose constant trickle into the farm’s system of canals was a reminder of the thirsty crop for which Koda Farms is celebrated.

“It’s pretty meditative, right?” asked Koda, the farm’s co-owner.

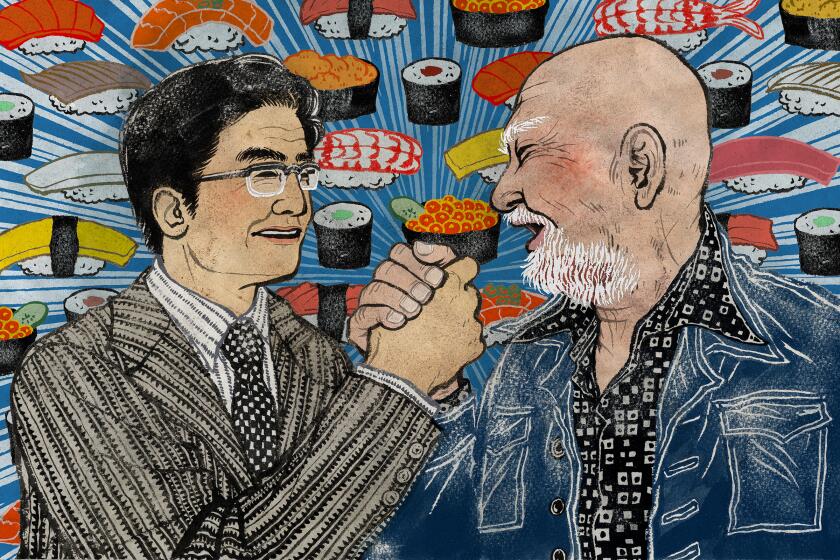

Koda Farms played a key role in the spread of sushi in Los Angeles in the 1960s, said Atsuko Kanai, daughter of Noritoshi Kanai, who helped popularize the cuisine in the Southland. Without Kokuho Rose, the farm’s special strain of medium-grain rice, his sushi gambit might have failed.

“There were a few things that made sushi possible — No. 1 and most pivotal was the rice,” said Atsuko, whose father visited Koda Farms in 1963 and struck a distribution deal to wholesale the Kokuho Rose rice to L.A. restaurants. “Koda Farms … [made] a more palatable rice that could be served in sushi.”

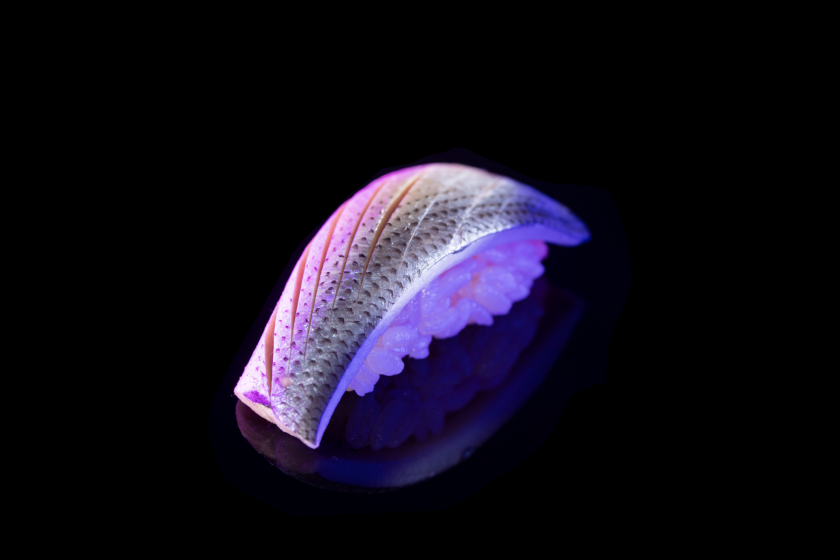

For Noritoshi Kanai, a Mutual Trading Co. executive, the prospect of his food-importing business bringing high-quality rice from Japan had been daunting — it would be too expensive. What’s more, much of the rice found in America in the early 1960s was of the long-grain sort, which wasn’t suitable for sushi. The food typically requires rice that is stickier than other varieties, helping nigiri retain its shape after being formed. Kanai, who persuaded the owner of Little Tokyo haunt Kawafuku to open a sushi bar around 1965, needed a local source.

An unlikely pair of Southern California businessmen paved the way for the sushi revolution in Los Angeles, upending American dining — and their own lives.

Launched in 1962, Kokuho Rose was developed by Koda Farms in conjunction with rice breeder Arthur Hughes Williams. The heirloom variety, Koda said, crossed a California medium-grain rice with a Middle Eastern long-grain to create a new, higher-quality medium-grain offering.

Koda said Kokuho Rose was envisioned by her grandfather, Keisaburo Koda, who founded the San Joaquin Valley farm in 1928, as a table rice. The variety, she said, “was not developed specifically to be a sushi rice — that’s just the application that [Mutual Trading] saw was useful to them.”

The rice was a revelation: Until the invention of this medium-grain strain, what had been available to make sushi in California was “tasteless, couldn’t retain moisture, and would get brittle as it cooled down,” said Anthony Al-Jamie, editor in chief of the Japanese culture magazine Tokyo Journal.

The son of a samurai turned rice miller, Keisaburo Koda was born in Japan in 1882. He immigrated to California in his mid-20s and pursued several ventures, including wildcatting for oil in the hills of Coalinga, a Fresno County town. He began farming rice in the late 1910s on leased land in Northern California. He wanted to buy property, but “no one would sell to Asians” there, Robin Koda said.

“He just literally kept moving south until he found someone who would sell land to him,” she said, adding that her grandfather started the farm by purchasing about 8,000 acres in South Dos Palos.

As a rice farmer, Keisaburo Koda became known for his innovations, including sowing seeds via airplane. In more recent years, Koda Farms’ rice has won acclaim from chefs and food publications. In 2020, Sunset magazine dubbed it the “Holy Grail of California Rice.” It is served at L.A. eateries, including M Cafe and Porridge + Puffs.

The owner of the Joint talks seafood, preservation and a sprawling new facility that will bring dry-aged fish to the masses.

After touring the rice fields, Robin Koda climbed into her Ford van, a spartan vehicle that shuddered angrily over the farm’s rutted roads. She drove a short distance before parking in front of a property that had been Koda Farms’ original headquarters — and now serves as a reminder of a dark period during World War II.

To rebuild like a mile down the road — to have this here as a daily reminder of what was wrongfully, illegally taken away from you — it’s sort of crazy.

— Robin Koda, Koda Farms co-owner and granddaughter of Keisaburo Koda, who founded the farm

Once the U.S. declared war against Japan in 1941, the government imprisoned Japanese Americans, including the Koda family. Notified that they would be sent to a detention camp in Colorado, they planned to temporarily close their farm, according to Robin Koda. But the government mandated that it remain in operation to support the wartime economy, so Keisaburo Koda had to hand over the management to non-Asians, she said.

When their incarceration ended, the Kodas returned to find that their prime property and equipment had been sold. “There was about 1,000 acres of scrappy land left,” Koda said. “Only junk remained; all the best stuff — it was totally picked over.”

From vegan sushi to hand rolls, modest supermarket sushi to high-end omakase — the greater-than-ever scene in L.A. has what you’re looking for.

But the family began building a new farm close by.

Looking at the original headquarters, which the Kodas never reacquired, Koda marveled at the strength of her family: “To rebuild like a mile down the road — to have this here as a daily reminder of what was wrongfully, illegally taken away from you — it’s sort of crazy.”

It isn’t just Atsuko Kanai who has touted the significance of Koda Farms’ contribution to L.A.’s sushi supply chain. Al-Jamie said that the creation of Kokuho Rose was “essential” to the spread of sushi across the region.

Without the heirloom rice, Al-Jamie said, “I don’t think [sushi] would have taken off” when it did.

But, in a twist, Kokuho Rose is no longer a sushi bar staple, with chefs now preferring short-grain rice. In the 1980s, Koda said, more Japanese short-grain rice became available in the U.S. market, which may explain the sea change. That rice, she said, is “more sticky” than Kokuho Rose, and “it seems to be a preference” among sushi chefs.

L.A.’s sushi revolution began in the 1960s at Kawafuku, a grand Little Tokyo restaurant whose story is one of glamour, heartbreak and innovation.

But that shift didn’t roil the company’s business. Far from it.

“We never would have pigeonholed ourselves into just sushi rice — you would cut your market down,” Koda said, explaining that her company’s two biggest products are its Sho-Chiku-Bai sweet rice and Blue Star Mochiko sweet rice flour.

Koda takes pride in carrying on the legacy of her family’s business — the one started by the man once dubbed the “Rice King.”

On that sweltering day in July, talk of ancestors filled Koda’s kitchen as she prepared rice for a visitor. She lives in a modest home on the farm that’s within view of the vast, metal-sided structures that house the machinery that processes Koda Farms’ rice crops. During the harvest, which typically begins in September, the workforce here swells to nearly 100 people.

She brought over a small bowl of cooked Kokuho Rose — one topped with a spoonful of briny salmon roe that contrasted nicely with the rice’s floral bouquet. Then she shared something that could have only been a dream in 1928, when her late grandfather founded Koda Farms, but had become a reality by 1963, when Kanai paid his fateful visit here.

“People just knew,” she said, “that if you wanted rice, the best rice was Koda Farms rice.”

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.