One almost has to admire Republicans for the tenacity and determination with which they keep coming up with new ideas for hobbling Social Security.

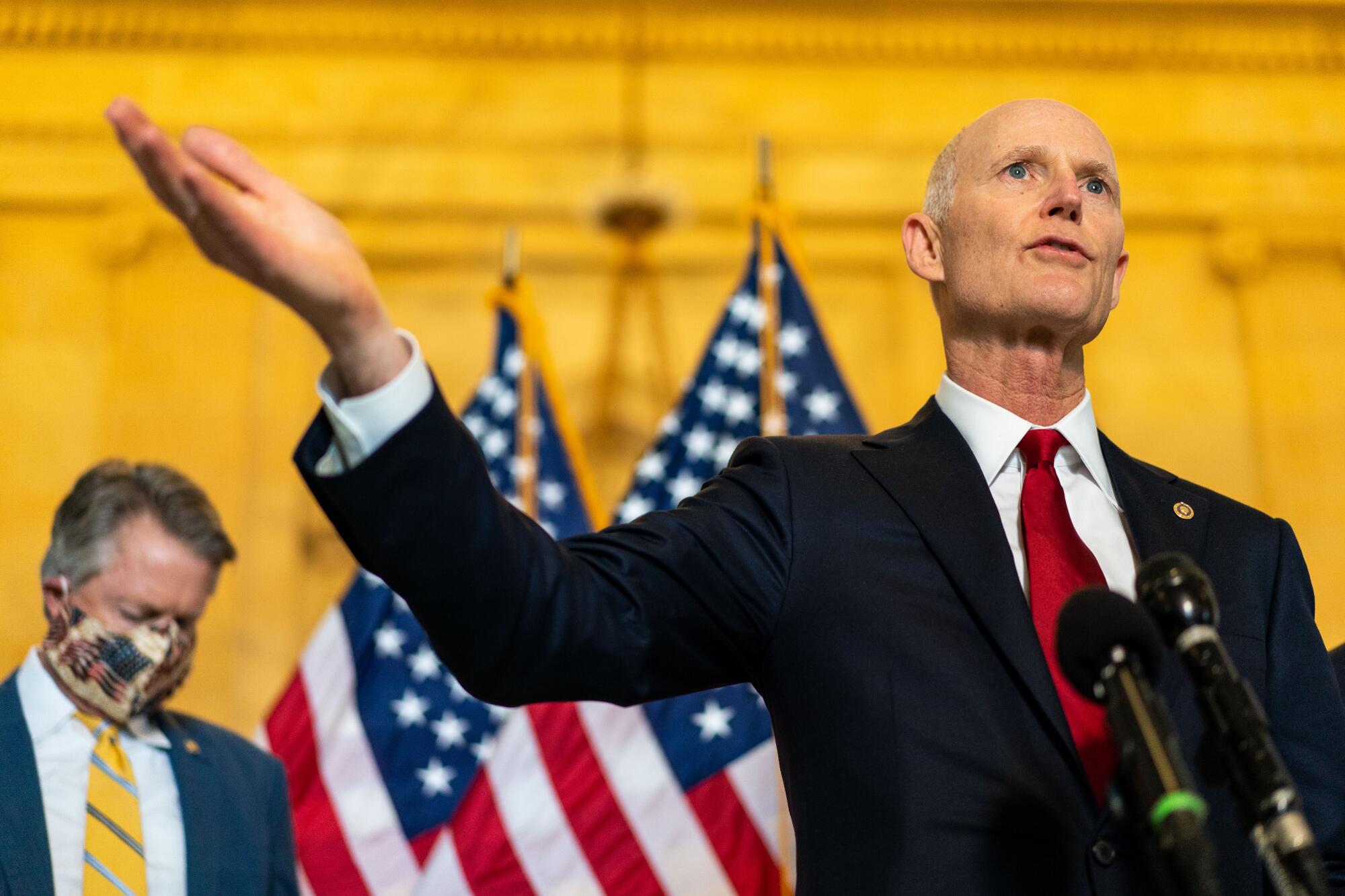

Just in the last few months, we’ve seen Sen. Rick Scott (R-Fla.) propose sunsetting Social Security and Medicare every five years, along with other federal programs, to give Congress recurrent cracks at zeroing them out.

Blake Masters, now the GOP candidate for U.S. Senate in Arizona, has proposed privatizing Social Security. “Get the government out of it,” he said in June, apparently unaware that a privatization plan crafted by President George W. Bush crashed and burned in 2005.

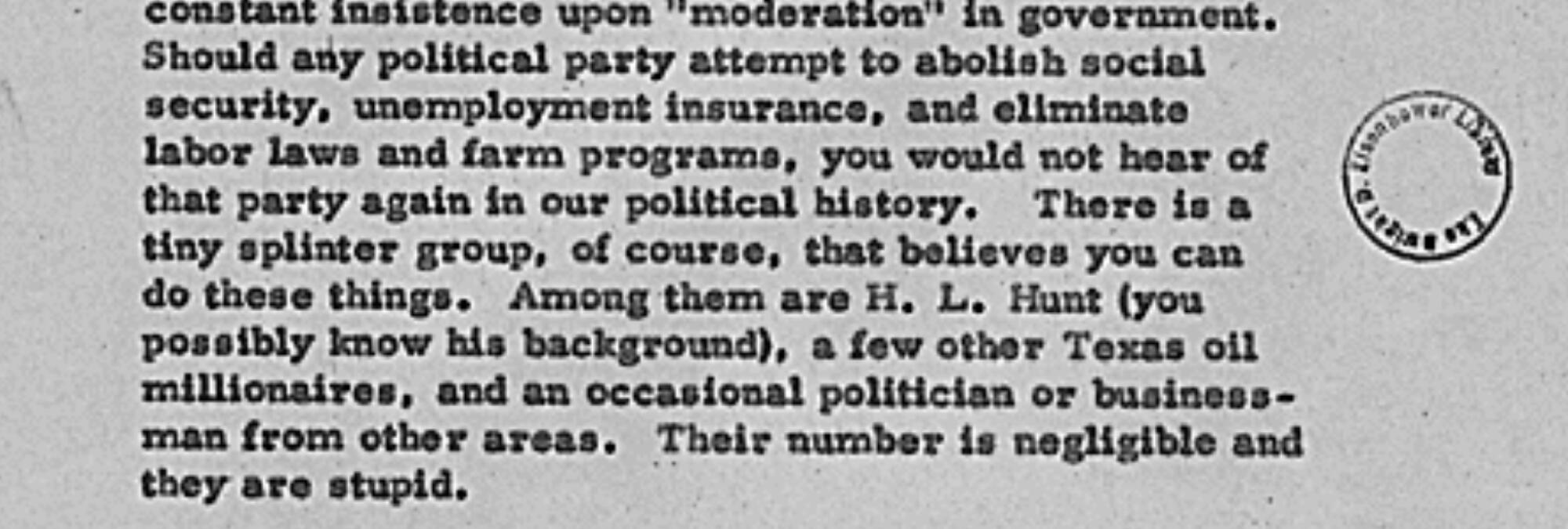

Should any political party attempt to abolish social security ... you would not hear of that party again in our political history.

— President Eisenhower, 1954

Then there’s Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wis.), who proposed eliminating Social Security and Medicare as permanent programs and converting them to discretionary budget items that would have to be evaluated by Congress every year.

Johnson observed that under current rules, “if you qualify for the entitlement, you just get it no matter what the cost,” as if that’s a bad thing.

Meanwhile, Republican Sens. Mitt Romney of Utah and Marco Rubio of Florida have proposed a federal family leave program that would be funded out of recipients’ future Social Security benefits, creating a retirement disaster for those who participate.

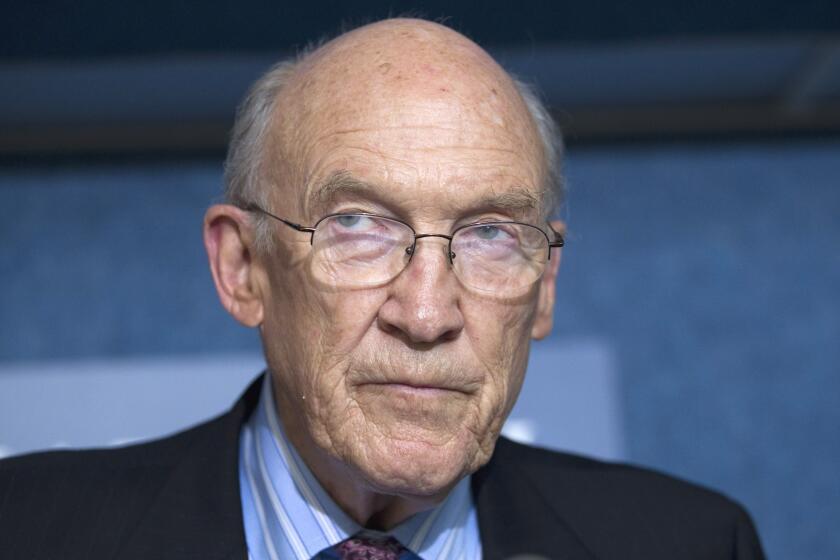

Former Sen. Alan Simpson worked to undermine Social Security. Why is he getting a Presidential Medal of Freedom?

The common theme of these proposals is that “the programs need to be withered away,” observed William J. Arnone, chief executive of the National Academy of Social Insurance, one of our most important advocacy organizations for these all-important programs, during a recent appearance on C-SPAN.

“Let’s say in 2024 we end up with a one-party government,” Arnone said. Plainly referring to the GOP, he added, “that one party that has a history of being against Social Security might say, ‘Here’s our chance.’”

What gives critics of Social Security the eternal hope that they can shrink or even eliminate the program is the notion, especially among younger workers, that it has become irrelevant to their futures. In fact, the opposite is true.

With the steady disappearance of corporate pensions, Social Security has come to play a larger role as a source of retirement income. In 1975, according to the Department of Labor, nearly 26 million American workers participated in so-called defined benefit pension plans, in which employers or unions shouldered the financial risk; by 2019, that figure had shrunk to 12.6 million.

Defined benefit plans have given way to defined contribution plans such as 401(k) plans, but participation rates are closely tied to income — 70% of those in the top fifth of income earners participate in their company 401(k)-type plans, but only 10% of those in the bottom fifth. That’s probably because those plans require workers to make contributions out of their paychecks, and lower-income workers may find it harder to scrape up the funding.

Other than retirement plans, most families have “little or no retirement savings” and “nearly half of families have no retirement account savings at all, Monique Morrissey of the labor-supported Economic Policy Institute documented in a 2019 paper.

How to Retire

The harvest is a looming retirement crisis in which only Social Security provides a guaranteed safety net. As many as two-thirds of all seniors get 50% or more of their income from Social Security, and more than a third rely on the program for more than 90% of their income, according to one estimate by the U.S. Census Bureau.

The program isn’t only for seniors, however. More than 3.8 million children ages 18 and younger receive benefits, typically as survivors of deceased workers or children of retirees or disabled workers. Benefits go to an additional 7.8 million workers with disabilities who have not yet reached retirement age.

These are the sorts of benefits that could not be offered by a privatized system, which almost certainly would tie benefits to the nest egg accumulated by workers and their families during a career and make them available only after retirement.

Except in cases of extreme hardship or with costly penalties, they’re not available to participants in defined contribution plans prior to retirement either.

That underscores the nature of Social Security as not merely a retirement program but insurance that helps protect families from the financial shock of a breadwinner’s disability or untimely death.

But those aspects can be unappreciated by younger workers, who may think about Social Security only when they contemplate the payroll taxes subtracted from their paychecks.

Improving Social Security is a matter of political will, not affordability.

The program’s opponents have long seen this disconnect as a wedge with which to weaken the program’s popularity. Back in 1983, for example, the libertarian Cato Institute published a paper proposing a “Leninist strategy” to wage “guerrilla warfare against both the current Social Security system and the coalition that supports it,” and promote privatization in its stead.

The authors, Stuart Butler and Peter Germanis, were anguished over President Reagan’s failure to exploit Social Security’s 1982 fiscal crisis to privatize the program. They concluded that the reason was the program’s strong support among the powerful voting bloc of seniors, compounded by the indifference of younger voters.

The answer, they concluded, was to undermine confidence in Social Security among the young. Their model was the Leninist movement’s “success in isolating and weakening its opponents.”

“The young are the most obvious constituency for reform,” the authors asserted, because they often express “little or no confidence in the present Social Security system” — doubts stirred up by conservatives’ incessant (and inaccurate) claims of the system’s impending bankruptcy.

Today’s Republicans have carried on this campaign, often by denigrating Social Security and Medicare as “entitlements,” by which they hope to suggest that their benefits are paid to undeserving recipients; in fact, the programs are entitlements because beneficiaries have paid for them through payroll deductions and other taxes.

In 2018, then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) described those programs as “the real drivers of the debt” and called for them to be adjusted “to the demographics of the future.” Translation: Benefits need to be cut.

The GOP was not always this determined to undermine Social Security. In 1954, for instance, President Dwight D. Eisenhower made this widely quoted observation in a letter to his brother Edgar:

“Should any political party attempt to abolish social security, unemployment insurance, and eliminate labor laws and farm programs, you would not hear of that party again in our political history. There is a tiny splinter group, of course, that believes you can do these things.”

Eisenhower identified that group chiefly as “Texas oil millionaires,” adding: “Their number is negligible and they are stupid.”

Nor did the party always buy into the ostensible “reforms” being proposed in its name. At a campaign stop in mid-August, Sen. Johnson argued that Social Security would have larger reserves than its current $3.9 trillion had it “taken the Social Security surplus back in the ’30s and just put it into a stock index fund.”

Leaving aside that stock index mutual funds didn’t exist in the 1930s — the first one was introduced in 1972 — the very idea of investing government funds in stocks was shunned by Republicans at that time.

At one hearing, Sen. Arthur Vandenberg (R-Mich.) asked Arthur Altmeyer, a Social Security staff member and future commissioner, how he proposed to invest a reserve fund that was expected to grow to $47 billion.

“You could invest it in U.S. Steel and some of the large corporations,” Altmeyer suggested.

Vandenberg threw up his hands in horror. “That would be socialism!” he exclaimed.

Instead, Congress mandated that the reserves be invested only in U.S. Treasury securities, the practice to this day. The idea of investing some portion of the reserves in the stock market bubbles up from time to time, usually during bull markets, when the possibility of investment losses appears remote.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

As I observed in June after the Social Security trustees released their most recent annual report, the U.S. is well-positioned not merely to maintain benefits but to increase and expand them.

The trustees calculated Social Security’s combined costs for retirees, those with disabilities and their dependents this year at about 4.98% of an economy valued at $25 trillion. Through the turn of the century, that percentage will peak at 6.18% in 2075, when gross domestic product is estimated to be more than $208 trillion, then will fall to about 5.87% through 2100, the limit of the trustees’ projections.

U.S. spending on public retirement and disability programs, as a percentage of GDP, is significantly lower than that of other developed countries such as Japan (10.5% of its GDP), Germany (12.5%) and France (15.3%).

Underscoring income inequality, America’s billionaires are already done paying their Social Security taxes for 2021.

The political challenge confronting the U.S. isn’t figuring out how to shrink Social Security, but how to improve it so it’s even more relevant to today’s workers, tomorrow’s retirees. Among the proposals is a bill dubbed Social Security 2100, introduced by Rep. John B. Larson and Sen. Richard Blumenthal, both Democrats from Connecticut.

The latest version of the bill has been criticized by some Social Security authorities for making some of its benefit increases temporary rather than permanent, and requiring smaller revenue increases than an earlier version.

On the whole, however, the measure, dubbed “Social Security 2100: A Sacred Trust,” would increase benefits across the board by an average of 2%, set a minimum retirement benefit at 25% above the federal poverty line and extend dependent benefits for students up to age 26 (the current cutoff is 19), among other improvements.

GOP Sen. Joni Ernst wants to ‘reform’ Social Security in secret, an indication that the public won’t like the result

On the revenue side, the bill would eliminate, over time, the existing cap on wages subject to tax, which is $147,000 this year — a level that in effect gives the 1% a pass on their obligation to support this universal system. The payroll tax is 12.4% up to that wage cap, shared equally by employer and employee. The earlier bill would have gradually increased the combined tax rate to 14.8% over 24 years.

These changes would improve Social Security’s stature as a bulwark against what Franklin D. Roosevelt called the “hazards and vicissitudes of life” — that is, the economic insecurity that comes with old age and other unexpected pitfalls.

The program’s survival isn’t dependent on economics or government finance, but on politics. What’s needed may be something like a reverse “Leninist strategy”: not positioning younger workers in opposition to their older compatriots, but making clear to them that they have interests in common with their elders.

“My concern is millennials and Generation Z,” Arnone told his C-SPAN audience, referring to cohorts ranging from workers now entering their 40s down to those still in their early teens. “A lot of them look at Social Security and say, ‘It’s not relevant to me — it’s great for Mom and Dad, it’s great for Grandma and Grandpa, what does it mean for me?’”

The task, Arnone said, is to “let them know, ‘You will need this program as much as your parents. They had pensions; you don’t.’ That’s where the battle will be.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.