He worked from home and died suddenly. Five days passed before his body was found

Dominic Green signed out of work as he always did, exactly at 4:30 p.m.

“Good afternoon everyone, my shift has ended,” the 28-year-old emailed from his desk in the living room of his Los Angeles apartment on a winter Wednesday afternoon.

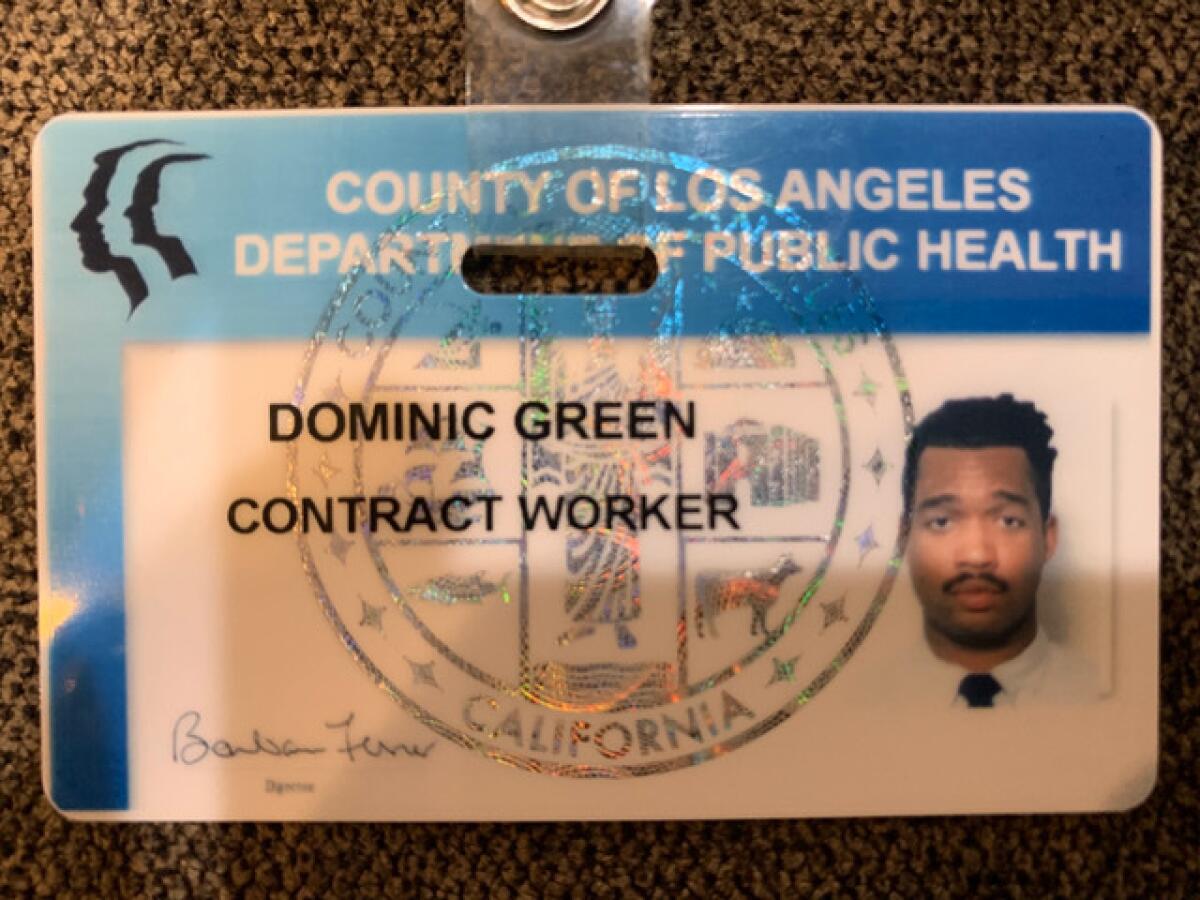

A remote contract worker, Dominic had never met any of his colleagues. A supervisor would later tell his father that she couldn’t pick him out in a photo. “We really don’t know people by anything except the work that they do,” he remembered her saying.

As the COVID-19 pandemic entered its third year, Dominic and his peers expected as much out of life. In 2020, Dominic’s classes went remote. His June 2021 graduation ceremony was held as a drive-through. And all of his job interviews were conducted by video.

Dominic, who was single and lived alone, had started his position as an epidemiologist in September, joining the 41% of white-collar workers who were fully remote, spending their days at home in jobs that were more disconnected and isolating than ever.

At the beginning and end of each shift, Dominic sent his bosses a mandatory email clocking in and out.

But the next day, a Thursday, Dominic didn’t send his 8 a.m. email. He missed the 4:30 p.m. sign-out too. Friday also came and went with no sign of Dominic.

Dominic’s parents, Joseph and Jeannine Green, who lived in Michigan, didn’t hear from him over the weekend, but that was not unexpected; they were used to waiting for texts from their busy son. But by Monday, which was Martin Luther King Jr. Day, they grew worried.

Joseph checked their family cellular plan and saw Dominic’s phone had been dark for five days. Jeannine checked their joint bank account and saw it too showed no activity.

By the time Dominic’s body was discovered in his apartment Monday night, he was unrecognizable and had to be identified by the few fingerprints still visible on his hands.

::

Late last summer, Dominic had packed up his things from his parents’ house in southern Michigan. He’d been taking classes from inside his bedroom since his campus, Loma Linda University near San Bernardino, shut down in 2020.

Like many young people, he moved across the country to start a new job in L.A. knowing few people in town but full of hope for the future.

Dominic worked as a contractor doing data entry at the Los Angeles Department of Public Health, tracking COVID-19 cases. It was his first job out of grad school, where he received a master’s degree in public health in June 2021.

He was hired by a company called Healthcare Staffing Professionals, which has provided the county agency with nearly 1,000 contractors since the pandemic began, 80% of whom worked remotely full time, like Dominic, according to a department spokesperson. Although Dominic was a “teleworker,” the staffing agency wanted him to live in the L.A. area.

The job paid well, and Dominic was excited that he could afford an apartment of his own, without needing roommates. He scoured rental listings and landed a one-bedroom in a three-story postwar building in Koreatown for less than $2,000 a month.

When Dominic’s parents came to town in October, they could tell that he was proud in his own quiet way, smiling to himself as he showed them around. His signature white Converse shoes were lined up at the door. Crisp, new dish towels hung in the kitchen. Dominic had always been meticulous, even as a child, making his bed of his own accord since age 4.

On his nightstand, Jeannine noticed the aromatherapy diffuser she had given him for Christmas. For the time being, Dominic slept on an air mattress.

Harry Sentoso, 63, went back to work at Amazon as part of the company’s hiring wave. Two weeks later, he was dead from COVID-19.

“I don’t know if I want to buy a bedroom set until I know if I’m going to stay in L.A.,” Dominic explained to his parents.

Dominic had a plan for everything in life, and much revolved around his career. He came from a family of professionals — his mother had been a registered nurse, his father had recently retired as a lieutenant colonel in the Air Force — and everyone knew him as “very Type A.”

The contractor job was a steppingstone, Dominic told his family, one that would get him closer to the next milestone — a doctorate in epidemiology, which he planned to use to help underserved communities.

Once he was financially secure, Dominic said, he’d start a serious relationship and, eventually, get married and have five children. Over 6 feet tall with an athletic build and an infectious smile, Dominic had full confidence in this part of the plan.

Dominic’s parents noticed how happy he seemed. He had a good job, a nice apartment, a car he loved.

But at the same time, the pandemic had shrunk Dominic’s world. He was an introvert by nature, and his main social contact had been through the classroom and daily workouts at the gym.

In L.A., he hardly left his apartment. To get out of the house at the end of the day, he’d hop into his Toyota Camry and take a long drive to pick up dinner. On nights and weekends, he boosted his resume with a part-time job doing academic research on sickle cell anemia.

Christmastime came. A big Marvel fan, Dominic was looking forward to the new Spider-Man movie, and his older brother, Adriel, hoped to see it with him over the holiday. But Dominic told his family that he couldn’t join them back in Michigan. He needed to study for a professional exam.

A few days after New Year’s, Adriel, who works as a doctor in Fresno, texted Dominic to invite him to go camping with his wife.

Dominic had always wanted to see Yosemite. But he said he had to finish a project for his part-time research job that weekend.

“I’ll have to bring bear spray if I go next time. Unless they’re hibernating 🤔,” Dominic joked.

It was the following week that his family noticed his unusual radio silence.

On the night of Monday, Jan. 17, Joseph called an L.A. number that belonged to someone who had sent Dominic two text messages that afternoon. He reached Lisa Smith, a supervisor at the county public health department.

“Dominic?” Smith asked, seeing a familiar out-of-state area code.

“No, I’m Dominic’s dad,” Joseph answered.

Smith said she hadn’t heard from Dominic since Wednesday and was concerned. But, she added, “Technically, he doesn’t work for us.”

The Greens asked a family friend who lived locally to head to Dominic’s apartment to meet the police for a wellness check.

As he waited, the friend went around back and climbed up to Dominic’s first-floor apartment. Peering in through the vertical slatted blinds, he could make out Dominic’s bedroom in the darkness, illuminated by the blue glow of the diffuser on his nightstand. There was Dominic on his bed, motionless.

He had probably been there for days, Joseph and Jeannine would learn.

“He’s not viewable,” the coroner’s investigator told them when they asked to see their son.

::

The Greens returned to L.A. to deal with Dominic’s things. They waited outside the apartment while a hazmat team in full body suits and respirators cleaned his bedroom. The team left carrying red bags of medical waste. An industrial fan remained on blast.

The Greens unzipped the plastic sheeting over the doorway and opened the door to Dominic’s apartment. The stench of death hit them from the hallway.

They wept as they packed his clothes and went through his possessions, sorting things to give away: his Yeti thermos, his free weights, his new bike with only four miles on it.

The Greens tried to piece together what seemed to be the last day of Dominic’s life.

Cleaning out the fridge, Adriel found a partially eaten Chipotle chicken burrito. The receipt showed Dominic had picked it up in Ladera Heights on Wednesday night.

Near Dominic’s Xbox, Adriel found a new video game controller that had arrived in the mail that afternoon.

It was a limited set of clues. Yet Dominic’s parents were comforted by the thought that their son had spent his final hours doing things he loved: eating Chipotle and gaming.

Other mysteries remained unsolved. They found boxes and boxes of clothes Dominic had recently ordered that still had all the tags. He spent more than $2,000 assembling a new wardrobe that was far dressier than his usual uniform of track suits and beanies.

But Dominic didn’t see anyone and had nowhere to go, his family puzzled. Maybe, they guessed, Dominic thought his office would reopen soon, and he wanted to have a nice set of work clothes.

Maybe Dominic had put together a set of church clothes in anticipation of going to in-person services again. Back in Michigan, he had attended virtual church services with his family; maybe Dominic had decided on a congregation to join in L.A.

They could only guess.

Compared with its ancestors, the latest Omicron subvariant, BA.5, may have an enhanced ability to create a numerous copies of the coronavirus once it gets into human cells.

Their work done, the Greens gathered in a circle in the middle of the apartment. Even wearing N95 masks, the smell was strong.

Devoted Seventh-day Adventists, the family held hands and began to sing a hymn. It was a song of hope, a central tenet of their faith:

Swift to its close ebbs out life’s little day;

Earth’s joys grow dim; its glories pass away,

Change and decay in all around I see;

O Thou who changest not, abide with me.

::

Back in Michigan, the Greens began to prepare for Dominic’s funeral.

Joseph asked one of Dominic’s supervisors at the county health department for some nice words to read at the service.

“Among the staff in my charge, Dominic stood out for being exceptionally punctual — he always logged in and out of his shifts precisely on time,” Nathan Lehman, a supervisor, wrote.

Joseph and Jeannine couldn’t understand why they hadn’t been contacted when their punctual son missed two days of work. Dominic had listed his parents and his older brother as his emergency contacts in paperwork for the staffing agency. All they needed was a phone call, and they would’ve found his body sooner, they thought to themselves over and over.

It was not as if Dominic’s absence over two work days had gone unnoticed. The Greens pieced together that Dominic had gotten emails and text messages from supervisors at the public health department, asking about his whereabouts. Attendance policies were strict, they noted as they read through his orientation materials.

“Dominic didn’t show up. Why didn’t you check on him?” Joseph asked Lehman by phone.

“I supervise 100 people,” said Lehman, adding that he was reluctant to get employees in trouble, Joseph recalled.

The Greens thought maybe there should be a law about calling emergency contacts. At the very least, they felt, employers had a moral responsibility to check on workers who don’t show up.

“The job is your first point of contact,” Jeannine said.

Arianna Garcia, a representative of Healthcare Staffing Professionals, said that the company’s practice is to contact the employee on the third consecutive missed workday and to notify emergency contacts if there’s no response.

The county health department said that if a contractor does not report to work, the agency’s procedure is to have the supervisor contact the contractor and also make a report to the staffing agency by the third missed workday. A spokesperson said that department staff followed all polices and procedures and “went above and beyond” by making “several efforts to contact Dominic through various methods starting on the initial no-show date, including on a non-working holiday.”

“Public Health takes the welfare of our workforce seriously and remains saddened by the passing of Dominic Green,” a spokesperson said in a statement. “In his time as a remote contract worker for DPH, Dominic’s hard work and dedication to public health left an impression on those with whom he worked.”

The Greens booked Dominic on a 10 p.m. flight out of L.A. on Friday, Feb. 4. His body arrived the next morning in Florida, where they had a family crypt near Orlando. Dominic would be buried next to his maternal grandfather.

Their tradition was to hold funerals on Sundays. Close family and friends gathered around the coffin the night before, when the Seventh-day Adventist sabbath ended, to visit quietly with the body, tell stories and draw strength privately before the whirlwind of a large funeral.

The Saturday night gathering was a family tradition from Jeannine’s religious upbringing in Haiti. She longed to hold Dominic’s hand and touch his face, to see him looking at peace in the casket, like he was sleeping. She wanted to tell him that she loved him and missed him. “I’m proud of you,” Jeannine would have told her son.

Planning the gathering, she, Joseph and Adriel discussed the possibility of opening the casket to get one last glimpse of him, even knowing what they saw would be imprinted on their minds.

But the day before the vigil, the family received bad news from the funeral home director.

“I’ll be honest with you,” she said. “Even with the embalming, he’s in pretty bad shape.”

Taking Dominic out of refrigeration on Saturday night, she explained, would be risky. After the sabbath, the Greens and close friends gathered without the casket. They looked at photos and told stories of his childhood as a military kid, living on bases from Japan to Massachusetts, traveling the world.

Doctors caution that rest is an important part of weathering a COVID-19 infection.

Joseph addressed the group and went over the schedule for Sunday.

“We can’t have a long service. If you’re in the program, stick to your time frame,” Joseph said. “They’re afraid that people are going to be able to start smelling him.”

Before the funeral Sunday morning, the Greens managed to get only a few rushed minutes with Dominic’s casket as the musicians were setting up. They wore Converse shoes, beanies, jeans and white button downs in tribute to Dominic, a casual but sharp dresser.

In the end, the Greens decided against opening the coffin.

The funeral home director had saved a lock of Dominic’s hair in a velvet bag, which Jeannine put in her purse.

Joseph looked out at the audience and delivered his remarks. Beside him was Jeannine, Adriel and Jeannelle, Dominic’s younger sister. Nearby, stood a life-size cardboard cutout of Dominic, smiling widely, a perfect picture of youth and vitality.

Hold your loved ones tight, Joseph urged. Check and make sure they’re OK.

“Please know that no employer is going to care for you like your family.”

::

In late May, four months after Dominic’s death, his parents received the results from his autopsy.

It was a natural death, the L.A. County medical examiner’s office found. Dominic, seemingly healthy, died of cardiomyopathy, a heart condition that can cause sudden death.

By all indications, Dominic got ready for bed that Wednesday night, lay down to sleep and simply never woke up.

“How many people out there may be single and don’t have somebody else at home to see that they’re OK?” his father asked.

::

For those in the college-educated professional class, Dominic’s path is a familiar one.

Life is largely organized around work and accomplishment. You get a degree and then, in your 20s, you work and work and work. You delay marriage and children, often striving for a financial stability that is more and more out of reach.

You move to cities thousands of miles away, leaving family and support networks such as friends or church, to take jobs that are increasingly not jobs at all but contract gigs.

Today, nearly 60% of workers whose jobs can be done remotely report that they work from home all or most of the time — almost triple the pre-pandemic numbers.

Many have come to prefer the virtual workplace. At the same time, a shift is underway, and much of white-collar work looks like this: someone working in their apartment, sitting at a computer in their bedroom or living room all day, alone.

::

After the funeral, the Greens received an e-sympathy card from Dominic’s colleagues at the public health department.

His co-workers wrote messages that were as sweet as one can write under the circumstances.

“Dominic was known by his strong work ethic and character,” wrote Smith, one of his supervisors. “Character is what a person does when no one is looking.”

Dominic was a fabulous epidemiologist, a great person to work with, a valued member of the team, others said.

“Dominic and I were in the same cohort and we onboarded together,” one woman wrote. “Though we only shared a few emails here and there, he was very kind and will be sorely missed.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.