Kaiser Permanente gets a special healthcare deal with California. Are Medicaid reforms in jeopardy?

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration has negotiated a secret deal to give Kaiser Permanente a special Medicaid contract that would allow the healthcare behemoth to expand its reach in California and largely continue selecting the enrollees it wants, which other health plans say leaves them with a disproportionate share of the program’s sickest and costliest patients.

The deal, hammered out behind closed doors between Kaiser Permanente and senior officials in Newsom’s office, could complicate a long-planned and expensive transformation of Medi-Cal, California’s version of the federal Medicaid program for people with low incomes or disabilities.

The agreement has infuriated executives of other managed-care insurance plans in Medi-Cal, who say it gives Kaiser Permanente unique standing and could cost them hundreds of thousands of patients and millions of dollars a year. The deal allows Kaiser Permanente to limit enrollment primarily to its previous enrollees, except in the case of foster children and people who are eligible for both Medicare and Medi-Cal.

“It has caused a massive amount of frenzy,” said Jarrod McNaughton, chief executive of the Inland Empire Health Plan, which covers about 1.5 million Medi-Cal enrollees in Riverside and San Bernardino counties. “All of us are doing our best to implement the most transformational Medi-Cal initiative in state history, and to put all this together without a public process is very disconcerting.”

Linnea Koopmans, chief executive of Sacramento-based Local Health Plans of California, echoed McNaughton’s concerns.

Medi-Cal, which covers roughly 14 million Californians, more than a third of the state’s population, was slammed in a state audit for failing to provide basic services, including child vaccinations, timely appointments for rural residents and adequate mental health treatment for people in crisis. To remedy these failings, the state has begun an ambitious contracting process that aims to commit the health plans to better service.

State officials hope that changes to Medi-Cal contracting will improve care for low-income residents and tighten accountability.

Insurance plans got wind of the backroom talks when broad outlines of the deal, which exempts Kaiser Permanente from a new statewide bidding process, were leaked days before the state briefed their executives Thursday.

Dr. Bechara Choucair, Kaiser Permanente’s chief health officer, argued in a prepared response that because it operates both as a health insurer and a healthcare provider, Kaiser should be treated differently from other commercial health plans that participate in Medi-Cal. Doing business directly with the state will eliminate complexity and improve the quality of care for the Medi-Cal patients it serves, he said.

“We are not seeking to turn a profit off Medi-Cal enrollment,” Choucair said. “Kaiser Permanente participates in Medi-Cal because it is part of our mission to improve the health of the communities we serve. We participate in Medi-Cal despite incurring losses every year.”

His statement cited nearly $1.8 billion in losses from the program in 2020 and said Kaiser Permanente had donated $402 million to help care for uninsured people that year.

Kaiser Permanente, the state’s largest managed-care organization, is one of Newsom’s most generous supporters and close political allies.

The new, five-year contract, announced publicly Friday, will take effect in 2024 pending approval from the Legislature — and will make Kaiser Permanente the only insurer with a statewide Medi-Cal contract.

It allows Kaiser Permanente to solidify its position before California’s other commercial Medi-Cal plans participate in a statewide bidding process — and after those plans have spent many months and considerable resources developing their bidding strategies.

Other health plans fear the contract could also muddle a massive and expensive initiative called California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal, better known as CalAIM, whose goal is to provide social services to the state’s most vulnerable patients, including home-delivered meals, housing aid for homeless people and mold removal from homes.

Under its new contract, Kaiser Permanente must provide some of those services. But some executives at other health plans say Kaiser Permanente will not have to enroll a large number of sick patients who need such services because of how it limits enrollment.

Critics of the deal noted Newsom’s close relationship with Kaiser Permanente, which has given nearly $100 million in charitable funding and grant money to boost Newsom’s efforts regarding homelessness, COVID-19 response and wildfire relief since 2019, according to state records and Kaiser Permanente news releases.

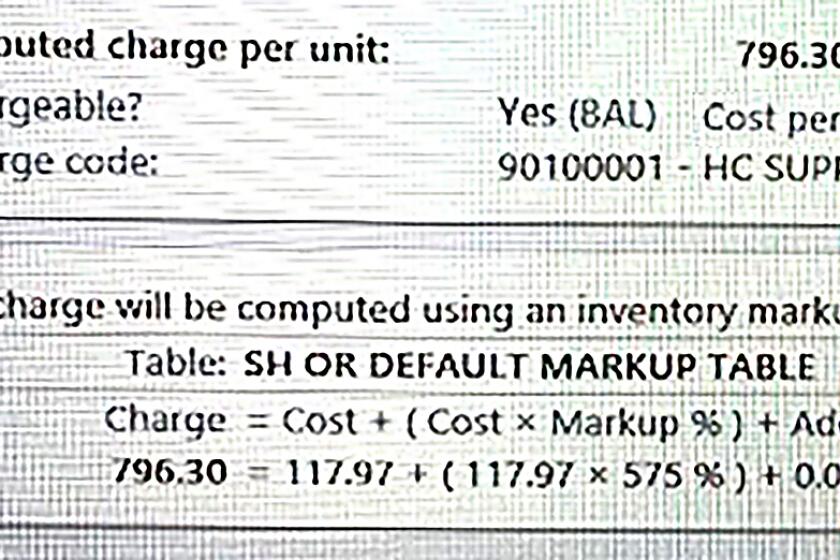

Screenshots of a system used by Scripps Memorial Hospital show markups of as much as 675% being imposed automatically during treatment.

The healthcare giant was also one of two hospital systems awarded a no-bid contract from the state to run a field hospital in Los Angeles during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, and it got a special agreement from the Newsom administration to help vaccinate Californians last year.

Jim DeBoo, Newsom’s executive secretary, was a Kaiser Permanente lobbyist before joining the administration. Toby Douglas, a former director of the state Department of Health Care Services, which runs Medi-Cal, is now Kaiser Permanente’s vice president for national Medicaid.

Still, many critics agree that Kaiser Permanente is a linchpin of the state’s healthcare system, with its strong focus on preventive care and high marks for quality of care. Many of the public insurance plans upset by the deal subcontract with Kaiser Permanente for patient care and acknowledge their overall quality scores may decline when Kaiser Permanente goes its own way.

Michelle Baass, director of the state Department of Health Care Services, said Medi-Cal had risked losing Kaiser Permanente’s “high quality” and “clinical expertise” altogether had it been required to accept all enrollees, as the other health plans must. But she said Kaiser Permanente will have to comply with all other conditions that other plans must meet, including tightened requirements on access, quality, consumer satisfaction and health equity.

The state will also have greater oversight over patient care, she said.

“This proposal is a way to help ensure Kaiser treats more low-income patients, and that more low-income patients have access to Kaiser’s high-quality services,” Baass said.

Though Kaiser Permanente has 9 million enrollees, close to a quarter of all Californians, only about 900,000 of them are Medi-Cal members.

Short-staffed employers are pressuring workers to stay on the job while feeling sick or with COVID-19. CDC guidance and testing disparities aren’t helping.

Under the current system, 12 of the 24 other managed care insurance plans that participate in Medi-Cal subcontract with Kaiser Permanente, keeping a small slice of the Medi-Cal dollars earmarked for a subset of Kaiser patients. Under the new contract, Kaiser Permanente can take away those patients and keep all of the money.

In its subcontracts, and in counties where it enrolls patients directly, Kaiser Permanente accepts only people who are recent Kaiser Permanente members and, in some cases, their family members. It is the only health plan that can limit its Medi-Cal enrollment in this way.

The new contract allows Kaiser Permanente to continue this practice but also requires it to take on more foster children and complex, expensive patients who are eligible for both Medi-Cal and Medicare. It allows Kaiser Permanente to expand its geographic reach in Medi-Cal to do so.

Baass said the state expects Kaiser Permanente’s Medi-Cal enrollment to increase 25% over the life of the contract.

Kaiser Permanente defended the practice of limiting enrollment primarily to its previous members, arguing that it provides “continuity of care when members transition into and out of Medi-Cal.”

The state has long pushed for a larger Kaiser Permanente footprint in Medi-Cal, citing its high-quality ratings, its strong integrated network and its huge role in the healthcare landscape.

“Kaiser Permanente historically has not played a very big role in Medi-Cal, and the state has long recognized that we would benefit from having them more engaged because they get better health outcomes and focus on prevention,” said Daniel Zingale, a former Newsom administration official and health insurance regulator who now advises a lobbying firm that has Kaiser Permanente as a client.

But by accepting primarily people who have been Kaiser Permanente members in the recent past, the health system has been able to limit its share of high-need, expensive patients, say rival health plan executives and former state health officials.

The executives fear the deal could saddle them with even more of these patients including homeless people and those with mental illnesses — and make it harder to provide adequate care for them. Many of those patients will join Medi-Cal for the first time under the CalAIM initiative, and Kaiser Permanente will not be required to accept many of them.

“Awarding a no-bid Medi-Cal contract to a statewide commercial plan with a track record of ‘cherry picking’ members and offering only limited behavioral health and community support benefits not only conflicts with the intent and goals of CalAIM but undermines publicly organized health care,” according to an internal document prepared by the Inland Empire Health Plan.

The No Surprises Act, which took effect this month, makes it illegal for hospitals to slap patients with sky-high charges for out-of-network care.

The plan said it stands to lose the roughly 144,000 Medi-Cal members it delegates to Kaiser Permanente and about $10 million in annual revenue. L.A. Care, the nation’s largest Medicaid health plan, with 2.4 million enrollees in Los Angeles County, will lose its 244,000 Kaiser Permanente members, based on data shared by the plan.

The state had been scheduled on Wednesday to release final details and instructions for the commercial plans that are submitting bids for new contracts starting in 2024. But it delayed the release a week to make the Kaiser Permanente deal public.

Baass said the state agreed to exempt Kaiser Permanente from the bidding process because the standardized contract expected to result from it would have required the insurer to accept all enrollees, which Kaiser Permanente does not have the capacity to do.

“It’s not surprising to me that the state will go to extraordinary means to make sure that Kaiser is in the mix, given it has been in the vanguard of our healthcare delivery system,” Zingale said.

Having a direct statewide Medi-Cal contract will greatly reduce the administrative workload for Kaiser Permanente, which will now deal with only one agency on reporting and oversight, rather than the 12 public plans it currently subcontracts with.

And the new contract will give it an even closer relationship with Newsom and state health officials.

In 2020, Kaiser Permanente gave $25 million to one of Newsom’s key initiatives, a state homelessness fund to move people off the streets and into hotel rooms, according to a Kaiser Health News analysis of charitable payments filed with the California Fair Political Practices Commission. The same year, it donated $9.75 million to a state COVID relief fund.

In summer 2020, when local and state public health departments struggled to contain the spread of COVID-19, the healthcare giant pledged $63 million in grant funding to help contact-tracing efforts.

Kaiser Permanente’s influence extends beyond its massive charitable giving. Its chief executive, Greg Adams, landed an appointment on the governor’s economic recovery task force early in the pandemic, and Newsom has showcased Kaiser Permanente hospitals at vaccine media events throughout the state.

“In California and across the U.S., the campaign contributions and the organizing, the lobbying, all of that stuff is important,” said Andrew Kelly, an assistant professor of health policy at Cal State East Bay. “But there’s a different type of power that comes from your ability to have this privileged position within public programs.”

Wolfson, Hart and Young write for Kaiser Health News, an editorially independent publication of the Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Health News is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.