Column: Leaked SoCal hospital records reveal huge, automated markups for healthcare

Ridiculous, seemingly arbitrary price markups are a defining characteristic of the $4-trillion U.S. healthcare system — and a key reason Americans pay more for treatment than anyone else in the world.

But to see price hikes of as much as 675% being imposed in real time, automatically, by a hospital’s computer system still takes your breath away.

I got to view this for myself after a former operating-room nurse at Scripps Memorial Hospital in Encinitas shared with me screenshots of the facility’s electronic health record system.

The nurse asked that I not use her name because she’s now working at a different Southern California medical facility and worries that her job could be endangered.

Her screenshots, taken earlier this year, speak for themselves.

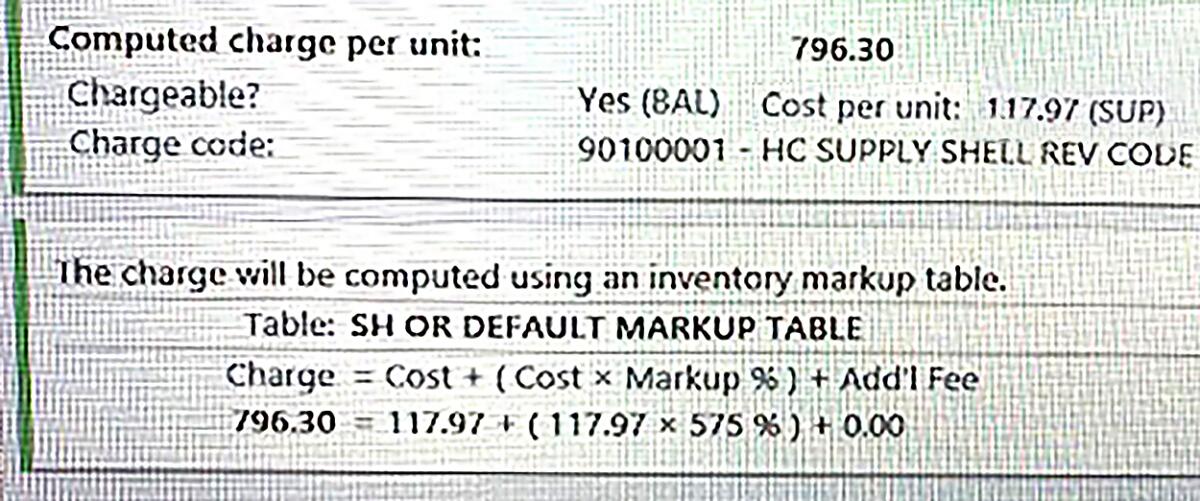

What they show are price hikes ranging from 575% to 675% being automatically generated by the hospital’s software.

The eye-popping increases are so routine, apparently, the software even displays the formula it uses to convert reasonable medical costs to billed amounts that are much, much higher.

For example, one screenshot is for sutures — that is, medical thread, a.k.a. stitches. Scripps’ system put the basic “cost per unit” at $19.30.

But the system said the “computed charge per unit” was $149.58. This is how much the patient and his or her insurer would be billed.

The system helpfully included a formula for reaching this amount: “$149.58 = $19.30 + ($19.30 x 675%).”

You read that right. Scripps’ automated system took the actual cost of sutures, imposed an apparently preset 675% markup and produced a billed amount that was orders of magnitude higher than the true price.

This is separate from any additional charges for the doctor, anesthesiologist, X-rays or hospital facilities.

Call it institutionalized price gouging. And it’s apparently widespread because the same or similar software is used by other hospitals nationwide, including UCLA, and around the world.

L.A. Pizza Hut customers are being hit with an extra charge to help recover “the increased cost of operations in the state of California.”

The former Scripps nurse said she decided to snap photos of the system as she watched stratospheric price hikes being imposed while a patient was still on the operating table.

She said one of her jobs in the operating room was to keep a running tally of all supplies used during a procedure. As she entered each item into the system, it automatically noted the actual cost and tabulated how much Scripps would bill for it.

“I understand that hospitals have overhead,” the nurse told me. “But to mark up something like sutures by 675% is insane.”

Another screenshot showed the pricing for an antimicrobial solution to clean the patient’s wound. Scripps’ cost per unit was $73.50. The billed amount was $496.13 — “$496.13 = $73.50 + ($73.50 x 575%)”.

Blades for a cutting tool used by the surgeon had a cost per unit of $98.53. Scripps’ billed price was $665.08 — “$665.08 = $98.53 + ($98.53 x 575%).”

“I started asking questions,” the nurse said. “I was told that if we didn’t mark things up like this, insurance companies wouldn’t give us what we want.”

This is through-the-looking-glass evidence of something I’ve written about repeatedly.

Healthcare providers routinely ignore the actual cost of treatment when calculating bills and instead cook up nonsensical figures to push reimbursement from insurers higher.

For the millions of people without health insurance, those sky-high prices are what they’re stuck with (although most hospitals, including Scripps, typically will offer discounts in such circumstances).

I wrote recently about a Valley Village woman who was billed $809 by a UCLA-affiliated clinic for a plastic boot for her broken foot. She found the exact same boot on Amazon for $80.

A UCLA-affiliated clinic charged more than $800 for a boot to treat a broken foot. The same exact boot can be found on Amazon for about $80.

Which is to say, she was being charged a nearly 1,000% markup.

But talking about it in the abstract or after the fact is one thing. Seeing a hospital’s computer system inflicting these price hikes while treatment is being administered — that makes the practice all too real.

A dose of Floseal to limit a surgical patient’s bleeding had a basic cost of $142.81, the Scripps screenshots show. The hospital’s charge: $963.97 — “$963.97 = $142.81 + ($142.81 x 575%).”

I shared the screenshots with Scripps and asked why such staggering price increases are apparently built into the hospital’s automated system.

Janice Collins, a spokesperson for the hospital, declined to answer beyond confirming that the higher amounts shown in the screenshots reflect the hospital’s “chargemaster,” the inflated list prices used for haggling with insurers.

Collins sent me a statement that characterized Scripps as a victim of circumstance, a reluctant player in a healthcare system “that was established decades ago and which is outdated.”

“Healthcare providers, including Scripps, negotiate with health insurance companies for what we will be paid for these services,” the statement said.

“Health insurance plans determine separately from healthcare providers what they will cover vs. what patients will pay,” it said. “Neither the insurance company nor the patient typically pay list price.”

None of this is inaccurate. But Scripps’ response merely danced around the edges of the issue at hand — namely, a major medical facility deliberately, and systematically, imposing huge markups that in no way reflect its actual treatment costs.

In California, you can’t be sued for consumer debt older than four years. But making even a partial payment can restart the debt clock.

Scripps’ software is from a Wisconsin company called Epic, which says its programs have compiled medical records for more than 250 million patients worldwide.

Epic’s healthcare systems include MyChart, the patient portal used by many hospitals, as well as a wide variety of applications intended for clinical settings.

Epic’s clients include UCLA, UC San Diego, UC San Francisco, Stanford University, Johns Hopkins University and Yale University.

“Automate revenue and coding from clinical activity to reduce administrative overhead, avoid missing charges, reduce A/R days and increase total revenue,” the company’s website says. (A/R is short for accounts receivable — the time that a payment is outstanding.)

I asked Epic if individual clients, including Scripps, request that the company tailor its software to their own needs by setting markups in advance.

“We don’t comment on our customers’ proprietary systems,” a spokesperson replied.

Asked to comment on his own hospital’s Epic system, Phil Hampton, a UCLA Health spokesperson, was similarly reticent.

“We know health insurance, billing and costs can be complicated,” he said, “and we encourage patients with questions to contact our agents for clarification, facilitation of resolution with insurers if needed and potential financial assistance.”

Scripps’ use of Epic’s software sheds new light on my last column about the hospital, which involved Scripps billing a patient nearly $80,000 for a procedure that Medicare said should cost less than $6,000 — a more than 1,200% markup.

The bill included a roughly $77,000 charge for “medical services,” which Scripps said covered “technical service charges” such as “the facility, the surgical room, the equipment, the support staff.” That is, the routine costs of running a hospital.

A single facility can’t be held accountable for the dysfunctional, profit-focused U.S. healthcare system. The issues raised here apply to every medical facility in the country.

But one common aspect of all U.S. hospitals is a desire to keep their pricing under wraps, to prevent patients from knowing how badly they and their insurers are being fleeced.

Maybe now that a smidge of sunlight has been let in, we can have a more honest conversation about fixing things.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.