(Jim Cooke / Los Angeles Times)

The global supply chain works like a giant circular conveyor belt that shuttles containers packed with goods from Asia to manufacturers and retailers around the world, then back to be refilled. But the belt has been clogging up at several key points along the way, causing delays to radiate through the system. As a result, products that rely on an Asian supply chain may be held up for more than a month, meaning they may be MIA this holiday shopping season unless they’re already on a boat steaming for a West Coast port.

To illustrate what’s gone wrong, let’s follow one container filled with a popular holiday gift — board games — from its manufacturer in China to its destination in the Midwest. Our guide on this trip will be Alex Schmidt, director of sales for the St. Louis publisher Stonemaier Games.

At the factory in Shenzhen

Like toasters, baby carriages, electric blankets and many other products, the vast majority of board games are made today in Chinese factories. The components for Stonemaier’s games — boards, cards, miniature figures and the like — are manufactured in Shenzhen, a Chinese tech factory hub near Hong Kong. “The supply chain issues start right here,” Schmidt said in an email.

Lately, the problem has been electricity shortages that have limited Shenzhen factories to one shift a day, said Jason Murray, chief executive of the ecommerce logistics company Shipium. The reduced hours, Schmidt said, mean that it takes about four months to print a game instead of the usual three.

The cutbacks stem from government efforts to reduce energy use and emissions in the country’s eastern industrial regions and higher coal prices that have hindered power companies. The problems ripple outward, limiting the production of basic materials and components and hampering the work of the factories that rely on them.

COVID-19 has also forced shutdowns in factories throughout Asia, including Vietnam, Malaysia and Myanmar, which has increased logistics delays for items such as apparel, shoes and semiconductors. Potential delay: one month

Getting to port in Yantian

After the games are boxed and put on pallets, they’re loaded into a container to carry them on their journey to Missouri. About 4,200 copies of a game like Wingspan — an ornithology-themed title in which players score points by bringing valuable birds into their habitats — will fit into one 40-foot container.

Herein lies the next problem: Containers have been in short supply for more than a year. Not only are there too few to handle the stepped-up demand for goods, but also the flow of containers to and from Asia has gotten badly snagged.

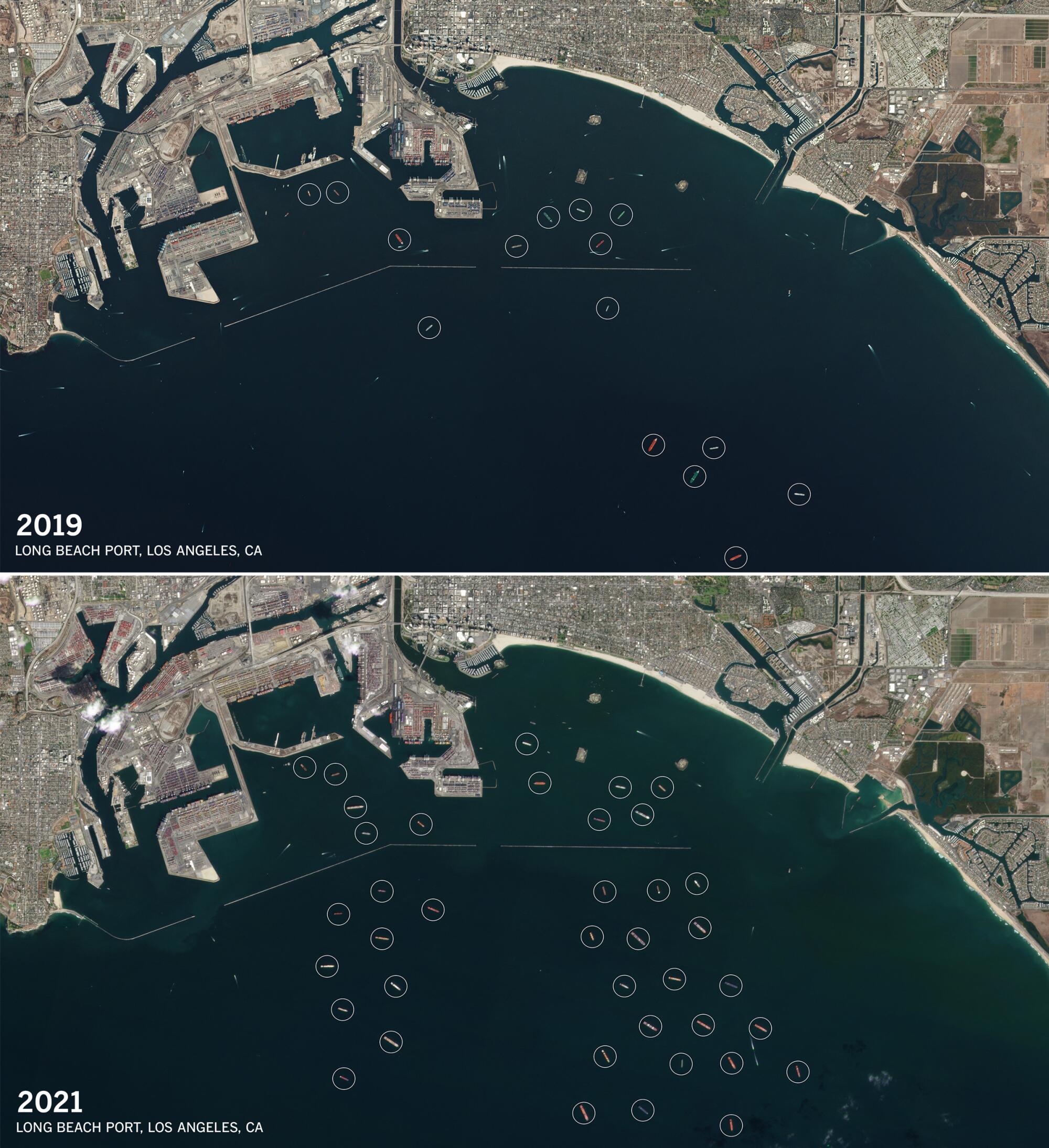

A global supply chain breakdown has resulted in gridlock at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach and beyond.

Ordinarily, vessels that deliver full containers from China spend extra time at the docks taking on empty containers to carry back across the Pacific. But with a growing line of other container ships waiting to be unloaded, and with customers in China needing vessels for their next shipments, “boats started to leave empty,” Schmidt said. “That meant containers weren’t making it back.”

Officials at the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles say that most ships leaving their docks are departing full. But they may not be filled with empties — the space can also be taken up by containers loaded with exports or imports bound for another U.S. port.

Getting the container onto a vessel

Having arrived at Yantian, Stonemaier’s container now has to be loaded onto a ship. Booking a trip through to St. Louis used to be easy, Schmidt said, because there were plenty of openings on vessels. “Now, it can take weeks or even months for our logistics company to even find a booking they can schedule.”

Another publisher, Sinister Fish, reported a delay of almost three months in booking shipment of a new game from China to Chicago.

Worse, Schmidt said, vessels are overbooked, and there’s a chance that the container will arrive at port to find that there’s no room available. “This is honestly the most uncertain and painful part of the entire process,” he said. “It’s just sitting. Will it get booked? Ever? You hope so, but there’s no guarantee.”

Getting space on a vessel is the biggest challenge in the global supply chain, said Sandeep Bhogaraju of Fractal Analytics. Part of the problem is the extra time it’s taking to load and unload ships because of China’s especially aggressive efforts to contain COVID-19, Murray of Shipium said in an email. Potential delay: Weeks to months

Crossing the Pacific

Finally aboard a ship, tucked among thousands of other containers, Stonemaier’s shipment churns toward the Port of Long Beach. There are two main sources of trouble here. The vessel may be stopping at other ports with long backups before heading to Southern California. And then there’s the weather.

Last winter, Schmidt said, a boat carrying three Stonemaier containers was hit by a storm and needed to limp into port for repairs. But the backups in Long Beach and Los Angeles meant there was nowhere to dock there, so the vessel headed to Mexico, delaying the shipment two additional months. Potential delay: Depends on the weather. Added cost per container: About $13,000

At the Long Beach anchorage

Arriving in San Pedro Harbor, the container ship from Yantian finds 40 to 70 other container ships waiting for a chance to dock. “When this started happening last fall, it was almost random what would happen,” Schmidt said, with some ships cutting the line and heading straight in while others waited for weeks. “Now, this part of the crisis has become so ‘normal’ that there’s a more orderly queue” — and two to four weeks spent anchored within sight of the port.

The number of containers coming into Long Beach and Los Angeles is up about 25% through September compared with last year. Ships are larger and able to carry more containers, which adds to the number of days it takes to unload, said Mario Cordero, executive director of the Port of Long Beach.

Container ships can’t easily sail to somewhere less busy. They often are under contract to deliver containers to that specific port from multiple companies, each of which has booked space on trains or trucks to carry its containers onward to their final destinations. “The backups are just long enough to be a major disruption to American businesses and consumers, but just short enough that it’s still cheaper to wait at sea for an open berth than to divert to a different port,” Murray said.

Nevertheless, ocean carriers sometimes bypass a swamped port because every day spent at anchor is enormously expensive, said Robert Khachatryan, chief executive of Freight Right in La Crescenta. To stock up for the holidays last year, one of Khachatryan’s customers booked a November delivery of two containers’ worth of kitchenware from a Chinese factory to the Port of Los Angeles. Rather than wait in a long queue there, the ship sailed to British Columbia, where its containers were sent by rail back to L.A. through Chicago because there’s no direct connection from that port to Los Angeles. “They got it into their warehouse sometime in February,” Khachatryan said.

There’s little financial recourse for companies whose wares are stuck in limbo. Shipping contracts don’t guarantee delivery dates, so the carriers aren’t liable for delays. Potential delay: Two to four weeks

At the Port of Long Beach

Finally at a port terminal, Stonemaier’s container is unloaded, only to wait for days on the dock. Each container has to be placed on a chassis (“think: a bed frame with wheels for a container,” Schmidt explained) so a trucker can haul it away, and given the logjam of containers and the shortage of trucks and drivers, that means a one- to two-week delay getting a ride out of port.

There’s also a pileup of empty containers, which tie up port space and truck chassis. Amid all the congestion, drivers who used to be able to pick up and deliver five containers a day now have to wait five to six hours per container, Khachatryan said.

The heavy workload is sapping dockworkers and their equipment, contributing to the delays, Khachatryan said. “You have equipment failing every day, you have people calling in sick every day…. People are burned out, the equipment is burned out.”

They’ve been stuck for months on cargo ships now floating off Southern California. They’re desperate

On ships caught in the huge floating traffic jam off L.A., seafarers with scant access to vaccines have been stuck in limbo for months. Unions tell of despair and violence.

The ports of Long Beach and L.A. have begun to operate around the clock, although the switch will take time and the demand for overnight unloading is uncertain. Also, some terminal operators contend that it won’t help to expand the hours to unload vessels while containers are piled up, waiting to be hauled away.

On Monday, both ports started charging ocean carriers a fee for not moving their containers out of the ports after a certain number of days, depending on the transportation method. The daily fine starts at $100 a container and increases in $100 increments each day a container sits beyond the limit. There are about 150,000 containers now sitting at the Port of Long Beach alone, waiting to be taken off the port or loaded onto an outbound ship. Potential delay: One to two weeks

At the warehouse or railyard

Ordinarily, Stonemaier’s container would be placed on a rail line at the port and moved by train to St. Louis, a trip that takes four to five days. But lately, Schmidt said, shippers haven’t been willing to go that route because it’s too hard to retrieve the empty container.

Tim Humbert, vice president of North American intermodal at the logistics company C.H. Robinson, said rail lines don’t deserve the blame for this problem. “A railroad is very good at moving their goods from point A to point B,” he said, but there aren’t enough truck drivers to move the containers to warehouses, and the warehouses don’t necessarily have the people needed to move the goods off the trucks. According to CNN, the problems in trucking are only getting worse, with the industry down a record 80,000 drivers.

Stonemaier has two options. It can send the container by train to Chicago, Schmidt said, where it confronts two layers of delay: the crush of trains trying to get into the yard, and the shortage of truckers to take containers on to their destinations. The other option is to have a truck take the container to a warehouse in Los Angeles, where the games are unloaded and then put onto a long-haul truck headed to St. Louis.

That second choice used to be “an option if you were willing to pay an extra $5,000 to get your product a couple of days faster than taking the train,” Schmidt said. “Now, it’s often the only option for delivery at all.”

But as in Chicago, it can be hard to find a driver. “I have about five containers at this stage that have been waiting about a week, which is the longest wait I’ve ever had for this step of the process. I don’t know how much longer it will take.”Potential delay: One or more weeks. Added cost per container: About $2,000 to $5,000

At the fulfillment center in St. Louis

Finally, the container arrives at Greater Than Games, a St. Louis publisher that handles fulfillment for Stonemaier. Workers there unload the games and start getting them onto delivery trucks bound for distributors, retailers and consumers.

Some other companies’ fulfillment centers are running into their own problems. “It still takes a lot of people to process orders,” Murray said. “But laborers appear to be quitting at faster rates, combined with frequent union disputes. As a result, there has been not enough labor to keep up with throughput.”

That means orders that should take a day to fulfill often take two to three times as long.

It’s taking longer to put some products in consumers’ hands too, Murray said, as some national delivery companies are limiting how many parcels can be sent by the retailers with whom they have contracts. The caps can cause deliveries to take two to three weeks longer than usual.

And these problems will only intensify as online orders surge during the holiday shopping season, Murray said. Major national carriers have already started raising prices and partnering with smaller delivery companies. The reason: They expect demand to be overwhelming.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.