Abrorizki Geraldy Aulia, the son of a ship’s captain, is part of the new generation that moves more than 80% of the world’s raw materials, parts and merchandise on commercial cargo fleets. At 24, he has already traveled farther by ship than most people ever will.

It’s heady stuff. Strange then, that he should feel so absolutely powerless.

Maritime union protections say Aulia should sail no more than 11 months a year on a contract with an employer-paid flight home at the end, but the Indonesian native has worked 15 straight months without a break. In June 2020, he boarded a cargo ship months before any country started vaccinating against the COVID-19 pandemic.

Aulia is a valuable piece of the engine that powers world commerce, but he is never allowed to leave his ship. Like hundreds of other sailors marooned in the massive floating traffic jam off the Southern California coast, he had long been unable to get vaccinated and so is restricted to ship.

Some 300,000 of these migrant merchant sailors have been stranded on vessels at sea or in ports around the world, according to the International Transport Workers’ Federation, a London-based trade union that is among the maritime agencies lobbying governments to address what’s been labeled the “crew-change crisis.”

They endure unbroken monotony and growing desperation. Their unions and charity groups describe exhaustion, despair, suicide and violence at sea, including at least one alleged murder on a cargo ship headed to Los Angeles.

Suicide prevention and crisis counseling resources

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, seek help from a professional and call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255). Text “HOME” to 741741 in the U.S. and Canada to reach the Crisis Text Line.

“It’s hard for me. I just hope my family understands why I’m not home yet,” Aulia told a reporter while his ship, the South Korean flagged vessel Pan Amber, used one of its own cranes to unload a shipment of steel. His bright orange uniform was so stained from his duties that he looked like an auto mechanic at the end of a very bad day.

Aulia, who earns $460 a month, said he never wanted a life working the seas, but the ties between this son and his father were binding. “His dying wish. For me to become a seafarer. I am fulfilling his dream. It’s not that I want to. I have to.” His other reasons are just as important because the money he earns is vital. “I am sending all of my money back home to my mother,” he said.

Aulia was one of the seafarers who answered the call in summer 2020 when weeks of pent-up consumer demand, powered by stimulus checks and cash stored up during lockdowns, started a tsunami of ocean-traveling goods.

It strained all parts of the global supply chain, causing ruptures still being felt today as dozens of cargo ships anchored outside Southern California ports wait to unload parts for factories, merchandise for retailers’ shelves and online orders destined for consumer doorsteps.

The Pan Amber, with its aging and sunburned orange and yellow paint job, had to wait only a few days for its turn to dock at the Port of Long Beach, the nation’s No. 2 behind cargo container champ and next-door neighbor, the Port of Los Angeles.

That’s because the Pan Amber is a small break-bulk freight carrier, which hauls loose cargo as vessels have done for thousands of years, and unloads at less crowded docks than container ships, which became dominant after the modern steel cargo box was invented in the 1950s and made shipping vastly more efficient.

Cargo ships, which range in size from huge to gargantuan, are labor-lean operations with a dozen to three dozen crew members. Most are paid meager wages and work long hours.

The vast majority of cargo vessels and their crews hail from foreign countries. Sixty years ago, the U.S. Merchant Marine ruled the waves of commercial shipping. Now U.S. flagged merchant ships number only 181, or 0.4% of the global fleet, because they are more expensive to build, repair and outfit with U.S.-citizen crews backed by strong unions.

Stress on sailors has been well known since at least 2012, when psychological studies examined relatively high suicide rates among seafarers who had experienced everything from pirate attacks to colleagues who went missing at sea to catastrophic and deadly accidents. Boredom is acute, but there are worse results.

A global supply chain breakdown has resulted in gridlock at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach and beyond.

Imagine weeks at sea or at anchor without the ability to contact loved ones, spotty Wi-Fi connections at ports, living on a food budget that amounts to $7.50 per person, per day. Imagine living in cramped quarters, confined to a 680-foot by 98-foot ship for months longer than you agreed to, your direct contact limited to a couple of dozen other crew members.

And the coronavirus has added a two-fold stress increase.

The unvaccinated crews fear catching COVID-19, and no U.S. port will allow unvaccinated seafarers to leave their vessels.

The same is true of other seaports around the world, said Stefan Mueller-Dombois, a ship inspector with the International Transport Workers’ Federation. All have barred them from the biggest respite they had, he said, which was getting off the ships while they are at port, as in the good old days of 2019.

“There are many concerns about their emotional well being,” added Samson Chauhan, a member of the Lutheran Maritime Ministry who travels from ship to ship at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach to provide religious and spiritual support.

“It’s like the seafarers are stuck in a prison,” Chauhan said. “All they see every day is steel and containers and other crew members. And what happens? Sometimes they collide with each other.”

Some crew members are having suicidal thoughts, Chauhan said. Some have acted on them.

Chauhan and others have been summoned to ships to provide spiritual and emotional counsel from other trauma.

“We were called in to arrange for Catholic chaplains to comfort the other crew members” who witnessed a September 2020 shipboard attack that left a supervisor dead, said retired Navy Capt. Dick McKenna, who serves as chief executive of the International Seafarers Center, a safe spot with a clubhouse atmosphere near the ports where seafarers can bunk, soak up all of the Wi-Fi bandwidth available and relax.

During the incident, Filipino sailor Michael Dequito Monegro used two knives to repeatedly stab his fellow crew member aboard the MSC Ravenna container ship as it traveled to the L.A. port from China, according to a U.S. Justice Department complaint filed in federal court in Los Angeles. Two witnesses heard Monegro tell the victim, “You are the one that destroyed my family,” according to an FBI agent’s affidavit.

In April, a body was discovered floating among the ships with an unspecified “injury to their upper torso,” according to the Long Beach Police Department. Homicide detectives are investigating. Only seafarers and other certified transportation workers are allowed in the area where the body was discovered.

The pandemic has created a paradox.

COVID-19 led to logjams at ports and borders that continue to ripple through many parts of our economy and everyday life. When will it get better?

Many seafarers haven’t been vaccinated against the coronavirus. But because they haven’t been vaccinated, the crews have been barred from leaving their ships to get their shots if the opportunity arises. As recently as Sept. 23, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was recommending that crew members should not leave their ships unless they needed medical care or would be isolated shoreside.

The fears are understandable, given the coronavirus’ ability to evolve into even more infectious variants.

In August, a cargo ship called the Global Striker arrived at San Francisco’s port and notified the Coast Guard that crew members were sick. Of the 21 aboard, 19 tested positive, four of them were hospitalized, three recovered after being on oxygen, and one died, Mueller-Dombois said.

To cope with the stress and the long hours, Aulia lives for those days when the ship is in a port and might have a decent Wi-Fi connection. If it does, he’s updating his Facebook pages and launching WhatsApp video calls.

“I miss my family,” he said. “I miss my Indonesian food” like nasi goreng, fried rice cooked with pieces of meat and vegetables.

At another dock at the port, the MV Ocean Satoko was delivering its shipment of concrete mix, notable for a light haze of cement dust around the ship. It was also on Mueller-Dombois’ list for ship inspections to make sure that seafarers were being treated well and paid what they deserve.

Its crew members had their typical seafarer game faces on at the start of every conversation, saying that everything was fine and that they had no complaints, as if any negative word might mean the loss of their jobs.

After a while, they warmed up and let a visitor in on how they pass the time.

A global supply chain breakdown has resulted in gridlock at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach and beyond.

Karaoke is big. They also watch DVDs of films, TV shows and old sporting events. Otherwise, everyone is replaying whatever they have managed to store on their smartphones or using the exercise equipment each ship is supposed to make available.

Third officer Jeffrey Estoreon Flores openly wondered whether he might have watched the Keanu Reeves cult action film hit “John Wick” “maybe more than anyone else, ever.”

“Our profession is quite difficult,” Flores added, noting that he had another five months of sailing before he could return to his home in the Philippines to see his wife, two sons and a daughter. “It’s even more stressful because we have to stay on board for such long periods of time. It’s a long voyage and we worry about the pandemic every day.”

Shipmate Reggie Teano Buendia acknowledged that he had watched the romantic Filipino soap drama “Dolce Amor” in its entirety. That doesn’t sound like a big deal, until he says it was 137 episodes.

Buendia was one of the few seamen that day who was able to look on the bright side of being confined to his vessel.

“I don’t mind not being able to leave the ship,” he said. “I just like to save money and this way I’m not spending any of it, and that is OK with me. I get to keep it all for my family.”

Once Mueller-Dombois was aboard, the ship’s master was sure to emphasize the thing that was on the top of his agenda.

Five times, Fe Mar Logronio Quintana asked if his crew was really going to get the chance to take part in an effort by the Long Beach and Los Angeles ports and the Long Beach Department of Health and Human Services to board ships at port and offer free Johnson & Johnson vaccines. To date, McKenna said, the program has vaccinated about 7,700 seafarers.

Once vaccinated, the workers may be able to visit, on their next trip, what had been one of their favorite perks of the Long Beach-Los Angeles seaport stay: the International Seafarers Center.

It’s one of hundreds of places in a loose worldwide network that offer respite, fellowship and just about anything a young sailor or an old salt might need at a foreign port of call. Wedged near a noisy 710 Freeway overpass, the clubhouse might be mistaken for the nation’s most modest Elks Lodge.

The owner of Kip’s Toyland thinks he’s outsmarted the global supply chain gridlock that is threatening the holiday shopping season.

The Seafarers Center had been on the verge of running out of money through much of its recent history, until it was discovered that its volunteer treasurer embezzled more than $1 million from the center and an Anaheim youth soccer league. The man pleaded guilty in 2019 and was sentenced to 10 years in state prison.

“Here we were with a couple of five-star seaports and a one-star seafarer’s center,” said Chairman Guy Fox, who oversaw refurbishment of the once-shabby center and its finances.

“First, we repainted it, then put new windows and doors in it, redid the roof and the floors. Then we put in bunkrooms and we redid the kitchen. Then we have an exercise room. Now we have to add a chapel to it,” said Fox, an international trade consultant.

The irony of the situation, manager Pat Pettit said, “is that none of the foreign seafarers can come here until they have been vaccinated.”

There was good news a few days ago for Indonesian seaman Aulia, who laments that his shipbound odyssey has prevented him from doing important things, like finding a wife.

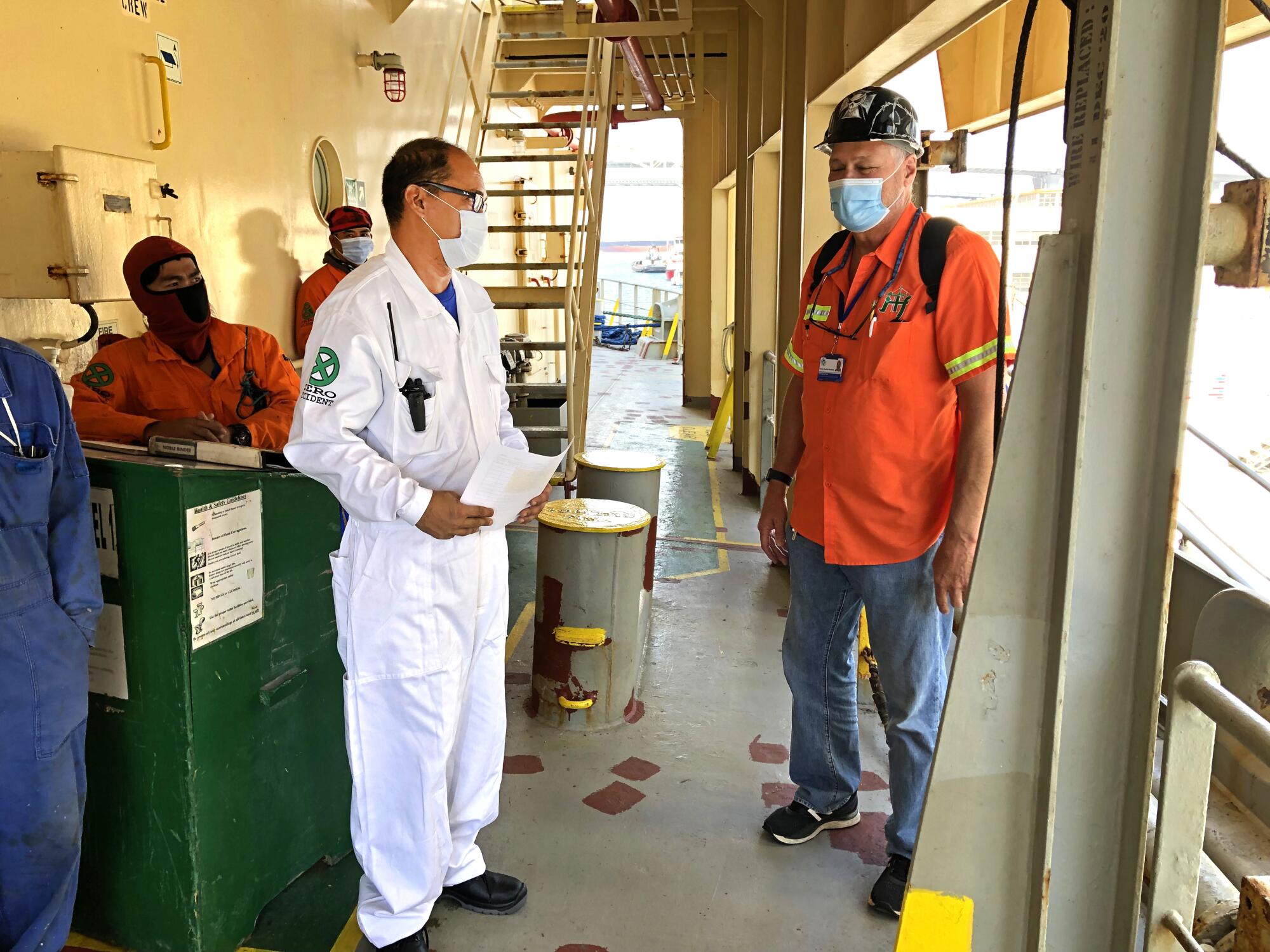

During the visit to the Pan Amber, inspector Mueller-Dombois’s very public conversation with Aulia about being forced to serve several months beyond his employment contract appeared to catch the attention of the ship’s officers.

Aulia soon learned that he and four other Indonesian crew members would be flying home, all after 15 months at sea. Almost better, Aulia got his Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.