Column: We learned nothing from previous oil spills. Will we learn from this one?

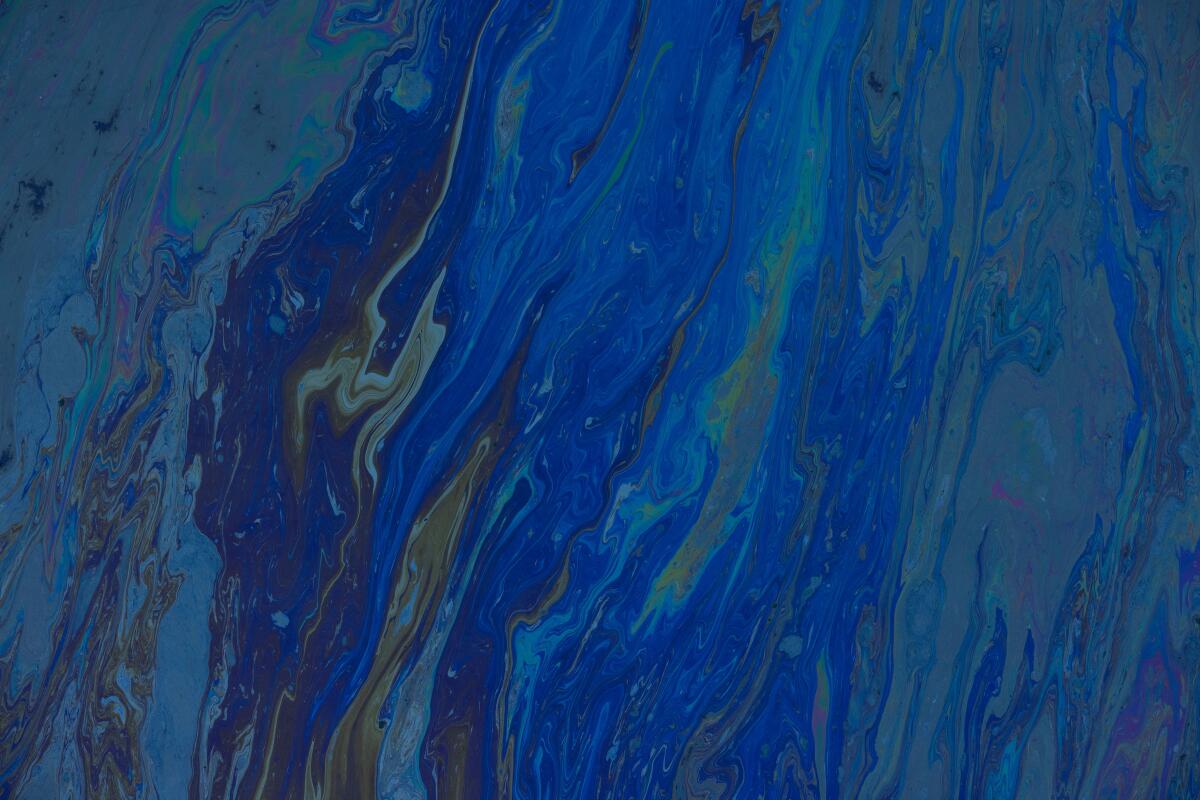

Miles of coastal beaches befouled. Shore birds and marine creatures killed by the scores, perhaps hundreds, perhaps thousands. Precious wetlands poisoned. Lax regulations exposed.

Those are the consequences of the Orange Country oil spill, which apparently began with a ruptured pipeline Friday, Oct.1, if not earlier. But they also describe the consequences of the Santa Barbara oil spill of 1969, and the Refugio oil spill of 2015.

Every time a major anniversary of those environmental disasters arrives, the airwaves and news columns are filled with musings over what we’ve learned during the previous five or 10 or 20 or 50 years. No doubt we’ll be reading the same, pegged to the latest spill, in 2026, and 2031, and 2071.

There is no such thing as a safe way to transport oil.

— Sierra Club, 2015

The answer to the question of what we’ve learned in the interim may well be the same: Nothing.

We can start with lessons learned from the Santa Barbara spill, which is the oldest major coastal disaster in modern memory.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

That spill, which followed the explosion of a well under a drilling platform in the Santa Barbara channel five and a half miles offshore, went unreported to Coast Guard officials for hours and minimized by the well’s owner, Union Oil, for hours, even days, longer. That obviously hampered the official response.

A similar delay apparently occurred in connection with the latest spill, as my colleagues Anita Chabria, Richard Winton, Rosanna Xia and Connor Sheets report. Once again, the public and authorities were left in the dark.

Although an oil sheen was spotted in federal waters off Huntington Beach on the evening of Oct. 1, Martyn Willsher, the chief executive of Amplify Energy, the pipeline’s owner, asserted that his company wasn’t aware of the rupture until Saturday, the next day.

The fossil fuel industry claims ‘renewable natural gas’ is green. It isn’t.

Environmental experts point out that offshore oil equipment is supposed to be safeguarded by systems that trigger alarms when anomalies that might indicate a potential spill occur. These include devices to detect sudden drops in pipeline pressure, which would signal a rupture.

“You don’t have pressure drop in a pipeline and not know about it,” Richard Charter of the nonprofit Ocean Foundation told The Times. “That raises the question: Why did the response kick in a day late? Somebody did nothing. ... You shouldn’t have to wait until the oil’s lapping up onto the shoreline to find out that you’ve had an oil spill. That’s ridiculous.”

But no authorities systematically check that equipment to ensure that it’s operational.

The history of the pipeline owner also hints at a long-term trend in the petroleum industry that can’t be good for the public interest: the shedding of capital-intensive functions, such as drilling and pipeline operations, by large integrated oil and gas companies.

Some of the big companies are also selling off fossil fuel assets as the threat of global warming places the oil economy under pressure.

As my Times colleagues report, Beta Operating Co., an Amplify subsidiary, operates the offshore platform at one end of the ruptured pipeline, which carries its crude oil more than 17 miles underwater to a pumping station in Long Beach.

Beta used to be a subsidiary of Bakersfield-based Aera Energy, which is co-owned by Exxon Mobil and Shell Oil (though both have said they want to divest themselves of the joint venture). But Aera sold Beta’s oilfield interests in 2007 to another company that then went bankrupt. After further proceedings, Beta’s owner emerged from bankruptcy as Amplify.

The California Independent Petroleum Assn., or CIPA, sued its critics and lost a $2.3-million judgment. That’s how it found itself in bankruptcy.

Amplify lost $464 million in 2020 on revenue of $202 million; in the first half of this year the company lost another $54.4 million; its management says it’s devoted chiefly to returning capital to shareholders — that is, extracting cash from its residual petroleum assets such as the offshore oil leases, and paying it to shareholders, presumably in the form of dividends and share buybacks.

“This is kind of in our DNA to return capital to shareholders,” Willsher told Wall Street analysts in August.

Shell, by contrast, reported revenue of $180.5 billion and profit of $5.6 billion last year. Exxon Mobil reported revenue of $202 billion and a loss of $13.3 billion in 2020, though it returned to profitability in the first half of this year.

The 1969 Santa Barbara spill revealed the extent to which the oil and gas industry exercised its economic power in Sacramento and Washington. Then-President Nixon had collected hundreds of thousands of dollars from oil industrialists such as Gulf Oil’s Mellon family, drilling executive Henry Salvatori, and the Pew family, whose fortune was tied to Sun Oil.

Nixon established a panel to investigate the oil spill, but five of its 11 members had business or professional relationships with Union Oil. Then-Gov. Ronald Reagan, whose election campaigns enjoyed generous financial support from California oil executives, never came to Santa Barbara to inspect its fouled shoreline.

That political clout persisted. At the 1980 Republican National Convention that nominated him for president, Reagan attacked federal regulations that discouraged petroleum development.

Corporations of all kinds are getting an earful from shareholders and the SEC about the need to disclose climate change impacts.

“Large amounts of oil and natural gas lay beneath our land and off our shores, untouched,” he said, “because the present administration seems to believe the American people would rather see more regulation, taxes and controls than more energy.”

Reagan’s efforts to reopen coastal waters to new drilling were stymied at first by a Democratic Congress, and subsequently by state regulations in California, Oregon and Washington.

The Santa Barbara oil spill all but created the nationwide environmental movement as we know it today. But that didn’t do much to prevent another spill in 2015, when an onshore pipeline ruptured and again fouled the Santa Barbara environment.

Reagan’s aggressive approach was intensified under Donald Trump. A plan released as Trump took office in 2018 aimed to open some 98% of coastal waters to new leases, including the shorelines of California, Oregon, Washington and Alaska. Trump proposed to reopen parts of the Atlantic and Arctic to drilling that had been barred by the Obama administration at least through 2022. Once again, lawmakers and states pushed back.

Although much new drilling may have been stymied by state regulations governing drilling in state waters and support facilities on land, regulation of existing operations has been beset by conflicts of interest by regulators and the phenomenon of regulatory capture, by which officials come to see things with the same eyes as the industries they regulate.

Joe Biden’s election points to historic gains in the fight against climate change.

As my colleague Steve Lopez points out, there’s been no lack of warnings that outdated underwater oil infrastructure is increasingly vulnerable to corrosion and leakage. Federal oversight is a thin reed, as the Government Accountability Office documented only a few months ago.

The Interior Dept.’s Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement, according to the GAO, neither monitors safety nor effectively enforces environmental rules; instead, it has allowed the oil and gas industry to leave 18,000 miles of abandoned pipelines underwater — 97% of the total — without confirming they have been properly cleaned out and decommissioned.

The Bureau “does not generally conduct or require any subsea inspections of active pipelines,” the GAO said. Rather, it relies on the pipeline owners to maintain warning systems. That’s a policy whose inadequacies are washing up on the shoreline of Huntington Beach as I write these words.

The solutions to these persistent issues aren’t hard to find. They mostly involve leaving oil in the ground. The rationale for that policy has only gotten stronger as the global warming caused by the burning of fossil fuels has become ever more evident.

“There is no such thing as a safe way to transport oil,” the Sierra Club warned in 2015, after the Refugio spill.

The battle against offshore drilling continues. Legislation reintroduced this year by Rep. Jared Huffman (D-San Rafael) and Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) would permanently ban oil and gas drilling in federal waters off the coast of California, Oregon and Washington.

Even if that were to happen, danger will still lurk under the waves. Will we still be seeing its effects when the anniversaries of the 2021 Orange County oil spill are marked, decades from now?

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.