Column: Trump loves fossil fuels; California wants clean energy. Cue collision

WASHINGTON — Donald Trump says he isn’t worried about climate change.

Before he was a presidential candidate, he said global warming was “a hoax” invented by China to kneecap the American economy.

“The climate has always been changing,” he shrugged more recently.

If he’s elected president, Trump says, one of his “Day One” priorities will be increasing oil and gas production — or, as he puts it: “Drill, baby, drill!”

With more fossil fuels, he promises, “we will be rich again and happy again.”

Those positions are at the heart of Trump’s campaign to regain the White House. And they put him on a collision course with California, where the Democratic-led government, supported by most voters, has made a clean-energy economy a major goal.

“It’s breathtaking how easily manipulated this man is,” Gov. Gavin Newsom said in a statement. “His only interest is pleasing Big Oil CEOs, and mortgaging our kids and the planet in the process.”

A large majority of Californians support their state’s ambitious climate goals, the Public Policy Institute of California found in a survey last year. Almost two-thirds said they believe protecting the environment should be a priority even at the risk of curbing economic growth.

In attacking the state’s environmental agenda, Trump frequently portrays California as a disaster zone, often in wildly exaggerated or invented tales.

Former President Trump is bashing California in his 2024 campaign; if he wins he wants to force it to change — on environment, immigration, LGBTQ issues and more.

“If you look at California, it’s got brownouts and blackouts every single day,” he claimed in a campaign video last year. “People can’t turn on their air conditioners.” (Not true; California hasn’t had significant power grid problems since 2020.)

If he wins a second term, Trump plans to scrap President Biden’s programs encouraging renewable energy. He has said he would offer tax breaks to oil, gas and coal producers; repeal federal subsidies for solar, wind and other renewable energy projects; and roll back Biden’s efforts to encourage the use of electric vehicles.

“First day in office, I’ll be ending all of that,” Trump said last year, referring to EV tax credits and other subsidies. (In fact, he couldn’t repeal the tax credit on Day One — that would take an act of Congress — but he could add requirements to limit the cars and trucks that qualify for the subsidy.)

Former aides say Trump is also likely to revive two of his first-term goals that spurred clashes with California: revoke the state’s tough vehicle emissions standards and open more federal waters to oil drilling, including off the Pacific coast.

He failed at both partly because of opposition from California and other states but also because of his administration’s incompetence.

“In the first term, the Trump administration had a kind of blunderbuss approach. Their proposals weren’t well thought out. They often didn’t hold up under close review,” said Richard M. Frank, a professor of environmental law at UC Davis School of Law. “Now they appear to be trying to learn from those mistakes. ... They could be a lot more strategic the second time.”

The clearest example is Trump’s attack on California’s tough automotive emissions standards.

Trump’s California-born advisor says he would deploy troops to blue states to seize undocumented immigrants, send them to camps, then expel them.

The 1970 Clean Air Act allows the federal Environmental Protection Agency to limit air pollution from automobiles. It also allows California to impose tougher standards because of its decades-long battle to reduce smog, under a “waiver” the EPA normally grants each year.

Congress also allowed other states to adopt the California standards; 17 states and the District of Columbia have done so.

In 2019, after automobile manufacturers complained that the California standards were a burden, Trump announced that he was revoking the state’s waiver “in order to produce far less expensive cars for the consumer.”

His decision was part of a broad effort to scale back federal rules requiring auto fleets to reduce fuel consumption.

Trump hasn’t officially won the Republican nomination. But he’s already throwing his weight around on foreign policy — and Republicans in Congress are falling in line.

Newsom and then-Atty. Gen. Xavier Becerra sued the federal government, charging that the EPA had overstepped its authority. The case meandered through the courts until Biden took office and restored California’s waiver.

Trump hasn’t talked explicitly about attacking California’s waiver again. But last year, the conservative Heritage Foundation assembled a team of former Trump aides to compile a policy agenda called “Project 2025.” The approximately 900-page document includes a detailed strategy for revoking or limiting California’s emissions standards.

It suggests that instead of revoking the waiver, the EPA could limit California’s standards to smog-producing pollutants like ozone, not greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide. If that fails, the agenda says, the EPA could try to block other states from adopting greenhouse gas standards.

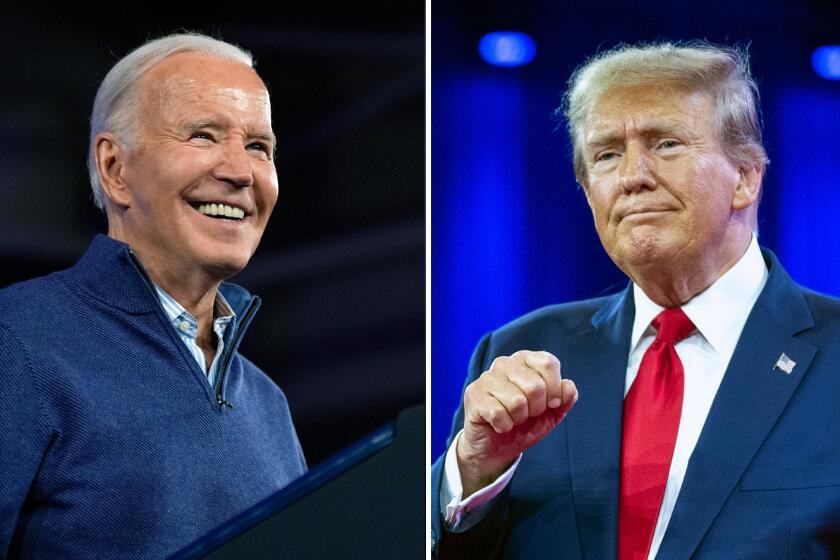

Biden and Trump offer converging narratives about the country: one optimistic, one apocalyptic. That collision is the core of the 2024 election.

“They’re recognizing that they screwed up the first time and laying out a road map to try to do better the second time,” said Dan Becker, an environmental lawyer at the nonprofit Center for Biological Diversity. “They’re basically choosing each of the areas in which California can act and going after each of them.”

Becker said the strategy may be aimed at getting the case into the Supreme Court, where a second Trump administration could try its luck before a 6-3 conservative majority.

If a second Trump administration tried to revoke the waiver, Newsom said at a February news conference, the state would go to court again.

“We know the playbook,” he said. “We were successful over and over [in Trump’s first term] in the courts, and we have confidence that will continue.”

Offshore oil drilling could produce another standoff.

In 2018, Trump proposed opening federal waters along the entire Pacific Coast, as well as Alaska and the Atlantic Coast, to drilling for oil and gas. That kicked up a storm of opposition, including — to Trump’s surprise — from Republicans.

And Trump’s administration found itself tied up in the federal rule-making process.

“They made procedural errors that slowed everything down,” said Kassie Siegel, an attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity.

If he wins a second term, Trump would have broad authority to open the continental shelf to oil leases, but he would run into other problems.

One is economics: Deep-water drilling in the North Pacific is expensive and risky. Oil companies are more interested in drilling in the Gulf of Mexico and Alaska, where known reserves are larger.

The other is local politics. In 2018, when Trump proposed opening the Pacific Coast to drilling, the California Legislature quickly passed a law banning new oil pipelines, piers or other infrastructure within three miles of shore. That could make it prohibitively expensive to move oil from offshore wells to onshore refineries or terminals.

Oil companies know that any attempt to drill new wells off California would spark massive opposition. A PPIC poll in 2021 found that 72% of Californians, including 43% of Republicans, oppose the idea.

Tariffs on foreign goods aren’t paid by other countries; they’re paid by American consumers — and they often fail to protect jobs.

A third potential conflict: wind. Offshore wind farms are a big part of California’s clean energy plans, aimed at supplying about 13% of the state’s power supply by 2045. But wind is Trump’s least favorite energy source.

“Windmills rot. They rust. They kill the birds. It’s the most expensive energy there is,” he charged last year. There’s much more to say about that, and I’ll return to it in a later column.

Newsom says he doesn’t believe Trump will get a second term.

“It won’t happen,” he said at the February news conference. Still, just in case, “we’re definitely trying to future-proof California in every way, shape or form.”

“We’re hardly just a punching bag on this,” the governor added. “We’re trying to assert ourselves.”

But environmentalists are still worried.

“The problem is, a second Trump term would come when the climate crisis is more dire than it was in his first term,” Becker said. “Everything the scientists predicted is happening more quickly than they expected. ... But Trump doesn’t believe it’s a problem, doesn’t want to solve it and would only make it worse.”

Which helps explain why so many environmental groups, including the Sierra Club and the League of Conservation Voters, have endorsed Biden’s reelection, even though they have criticized many of his decisions: They’ve considered the alternative.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.