New California labor law AB 5 is already changing how businesses treat workers

At Yogala Studios, a small, cozy storefront in Echo Park, the teachers work mostly part time, some giving just one class a week. Workshops are offered in “the ancient spiritual, philosophical and meditative traditions of yoga and tantra,” as well as in “meditation to tap into our creative potential to move through negative blocks.”

Recently, though, the studio has had to confront a very modern challenge: It is reclassifying its instructors, who had always been independent contractors, as employees with extensive labor protections because of California’s sweeping new law, Assembly Bill 5.

They aren’t complaining. “These are yogis,” said owner Samantha Garrison. “They look on the bright side of things.”

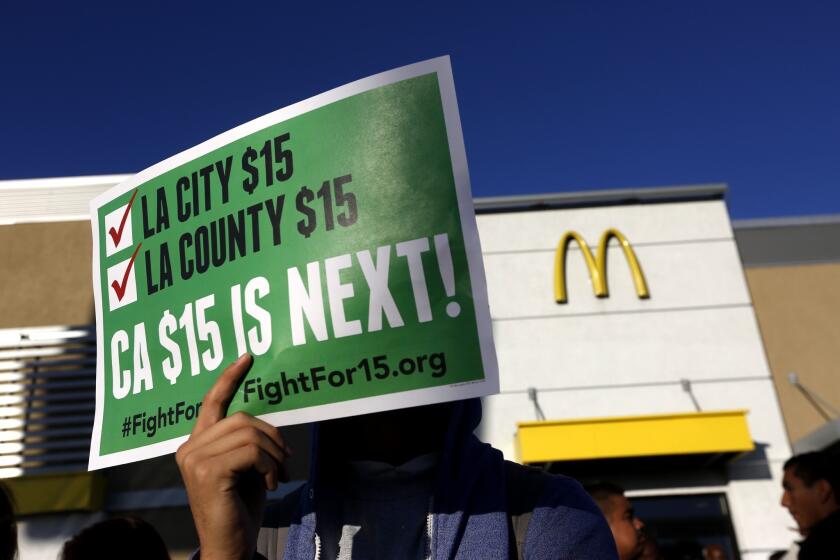

Across California, AB 5 is upending workplaces, prompting lawsuits, furious social media campaigns and a multimillion-dollar ballot initiative, sponsored by Uber, Lyft, Postmates and DoorDash, which are refusing to grant employee status to their tens of thousands of drivers.

But as critics demand exemptions and even a repeal of the statute, many California businesses, large and small, are quietly adopting strategies to comply with the law, which took effect last month. It hasn’t been easy.

AB 5 sets a new standard for hiring independent contractors, requiring many to be reclassified as employees covered by minimum wage, overtime, workers’ compensation, unemployment and disability insurance.

With companies also having to cover employees’ Social Security and Medicare taxes, costs can mount. “I knew I needed to bring in more money,” said Garrison, who raised her prices from $22 to $26 per class.

So far, her clients aren’t upset, she said. “I reached out to every member. But it’s been a huge headache — a lot of paperwork and technicalities.”

The new law grew from a 2018 California Supreme Court decision in a case brought by drivers for Dynamex Operations West, a package delivery company. The court found the company illegally switched its workers’ status from employees to independent contractors to boost profits.

Workers have brought similar misclassification cases across the U.S. for decades as companies offloaded once-stable jobs to independent contractors and temporary help agencies in what some experts call “a fissured workplace.” But the nation’s growing income inequality is spurring a push for stricter laws.

In California, industries such as construction, janitorial, trucking — and even yoga — had fought to retain independent contractors under a set of complex rules that the Dynamex decision scrapped, replacing them with a tightened, simplified test.

To be independent contractors under the court’s new “ABC test,” modeled on laws in Massachusetts and several other states, workers must (A) work independently, (B) do work that is different from what the business does, and (C) offer their work to other businesses or the public. All three conditions must be met.

Under prong “B” of the standard, a yoga instructor working for a yoga studio would not qualify as an independent contractor any more than a driver for a transportation company, a drywaller for a home builder, a maid for a cleaning franchise, a caddie for a golf club or an actor for a theater.

Roughly a million California workers may need to meet the ABC test to continue as either part-time or full-time independent contractors, the state Legislative Analyst’s Office estimated this week. The tally excluded tens of thousands of self-employed truckers, freelance writers and drivers for ride-hailing and food-delivery technology platforms whose status is under review in court cases.

The new law has companies scrambling to consult with labor lawyers, accountants and human resources specialists on how to avoid the lawsuits and regulatory fines that can result from misclassification. Penalties for violations range from $5,000 to $25,000, and companies can be liable for back wages.

“There’s no industry out there that hasn’t tried to dabble in independent contractors,” said Anna Towne, an executive at Bizhaven, a Sacramento consultant. More than 30 businesses, including construction, farming and tech companies, have sought her firm’s advice on how to comply with the law, she said, and nearly all have switched their independent contractors to employee status.

“Some want to fly by the seat of their pants,” she added. “But we explain it’s not worth risking their business. They could get into hot water.”

For California businesses, 2020 will be a year of reckoning. Sweeping new laws curbing long-time employment practices take effect, aimed at reducing economic inequality and giving workers more power in their jobs.

Towne also stresses the positives. “As an employer, they have much more control,” she said. “They can dictate what’s expected, how much time to spend, how to work with clients and with their other employees. With independent contractors, you can’t have that type of control.”

In one respect, AB 5 narrowed the reach of the court decision. It carved out a score of occupations such as physicians, lawyers, insurance and real estate agents, engineers, stockbrokers and others seen as having bargaining power over their working conditions. The bill’s author, Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez (D-San Diego), is drafting a bill to exempt a few others, including musicians, freelance writers and photographers. But most industries, especially those that use low-wage workers, are likely to remain covered by the ABC test. Others can still be sued for misclassification under the previous looser rules.

Accountants are among AB 5’s exempted professions, but during tax season, they traditionally hire independent contractors to help file clients’ returns and process payrolls.

“The law is having an immediate impact,” said Anthony Pugliese, chief executive of the California Society of Certified Public Accountants. His 45,000 members, he said, use “armies of temporary paraprofessionals. Thousands — it could be tens of thousands — are now being put on payroll, signed up for withholdings and offered benefits.”

Pugliese doesn’t oppose AB 5. “You wouldn’t have this law if there wasn’t some abuse where companies keep people as temp workers for a year, two years,” he said. “At some point it’s like — this is a real employee, why are you treating them like this?”

But his association is preparing daylong training sessions on AB 5 compliance “because there’s so much gray area,” Pugliese added. Temporary tax return preparers often work 90 or 120 days between January and April, he said, “but what if I’m only using them for a week? Who wants benefits for a week? It doesn’t make sense.”

A “business-to-business” exemption in AB 5 allows contractors who set up a sole proprietorship, a limited liability corporation, a partnership or a corporation to avoid the ABC test if they meet certain criteria. In recent months, hundreds of truckers who own their own big rigs at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach have set themselves up as independent businesses in hopes of qualifying.

Sheila Scoville, president of Omni Therapy, a 30-employee Los Angeles referral agency, is one executive hoping the business-to-business provision will save her company — but she isn’t sure. Omni connects healthcare agencies to physical, occupational and speech therapists who work as independent contractors helping elderly patients recover from strokes or surgery in their homes.

Unlike physicians, dentists and psychologists, those therapists were not exempted from the law, which is aimed at ensuring that therapy businesses pay their workers, most of whom work on-site, as employees and offer them labor protections.

But Scoville argues that the roving professionals she refers may be paid by healthcare agencies, hospitals or Medicare and don’t necessarily work for Omni, although she has handled their paperwork and takes a cut of their fees. When the California Employment Development Department audited Omni under pre-AB 5 rules, “they interviewed our therapists, reviewed my text messages and emails, looked at clinical notes, and last year after 18 months of pain, I came out with zero liability,” she said.

But if the ABC test were applied, and the 500 therapists on Omni’s roster were deemed her employees, Scoville calculated that workers’ compensation alone would cost her nearly a million dollars a year.

As a work-around, after consulting attorneys, she informed all 500 therapists they would have to get their own business licenses or LLCs. Over the last month, some 150 quit. “They weren’t happy,” she said. “They are afraid of the law.”

Now, Scoville added, “I’m looking into providing services in other states. We started this month in Arizona. I don’t know how long I can keep going in California.”

For-profit businesses aren’t the only employers having to adapt to the law.

“AB 5 hit us like a ton of bricks,” said Christian Lebano, artistic director of the Sierra Madre Playhouse, one of 28 small nonprofit theaters in the Los Angeles area. “No one makes a living in small theater. Actors and designers do it because they love the work or want the exposure.”

On Jan. 28, Sierra Madre canceled its annual youth production. Nine school districts had booked seats for the March adaptation of “Charlotte’s Web,” with 2,600 children, along with 400 teachers and parents, planning to attend. But paying actors and other personnel minimum wage and overtime for six weeks of rehearsals and 46 performances, along with payroll taxes and other employee costs, would have added $38,000 to a $52,000 budget, Lebano said.

The theater’s summer production schedule will continue as planned because it was already budgeted for union-covered actors, he said. As a result of AB 5, however, three stage managers will switch from independent contractors to employees.

North Hollywood’s Deaf West Theatre, which offers plays in sign language, has also been forced to adapt. Its actors and stage managers were already employees, but for its next production, 11 people will gain employee status, including the director, producer, designers and sign-language interpreters.

“We are trying the best we can to be in compliance, while keeping our company afloat,” said Deborah Reed, the theater’s business manager.

Small theaters and dance and opera companies are pressing for an AB 5 exemption, but Actors Equity Assn., the national union for actors and stage managers, backs the law as is. “Those who bring a show to life should be fairly compensated and have the same standard protections that employees in other industries have,” Executive Director Mary McColl said.

Last month, the group released a survey of union and nonunion actors and stage managers treated as independent contractors. Eighty-two percent reported being asked to work for less than minimum wage, 28% reported being denied unemployment benefits and 16% reported being injured while working, including falls during dance lifts — injuries not covered by workers’ compensation.

Few California politicians have written more far-reaching laws in recent years, from workplace rights to election rules, than Lorena Gonzalez. Now the San Diego Democrat faces what could be her toughest fight of all.

Gonzalez, the AB 5 author, is not offering a carve-out for performing arts groups. But earlier this month, she and other legislators proposed a one-time $20-million state budget appropriation for grants to small arts organizations “that make a good-faith effort to comply with AB 5.”

Meanwhile, enforcement of the law is underway.

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s budget allocates $21.68 million to crack down on misclassification under AB 5, and to process an expected jump in workers’ compensation claims. It grants contractors a one-year exemption from state fees normally assessed to set up LLCs and limited partnerships.

The state has set up a detailed website and scheduled more than 80 seminars across the state to explain the law. At Glendale’s Verdugo Jobs Center last month, two Employment Development Department officials projected 41 slides on AB 5, distributed fact sheets on the underground economy and answered questions from some 30 attendees.

The three-hour session delved into rules for language interpreters, nurses, plumbers and construction and restaurant workers. A woman who hires independent contractors to sell flowers on the street wondered whether she was exempt. An insurance agent expressed frustration that “calling EDD is like falling into a deep hole. They never call you back.”

Ken Johnson, one of the EDD presenters, sought to reassure. “Our goal is to level the playing field for all employers,” he said. “We’re asking you all to help the effort.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.