Wage inequality is surging in California — and not just on the coast. Here’s why

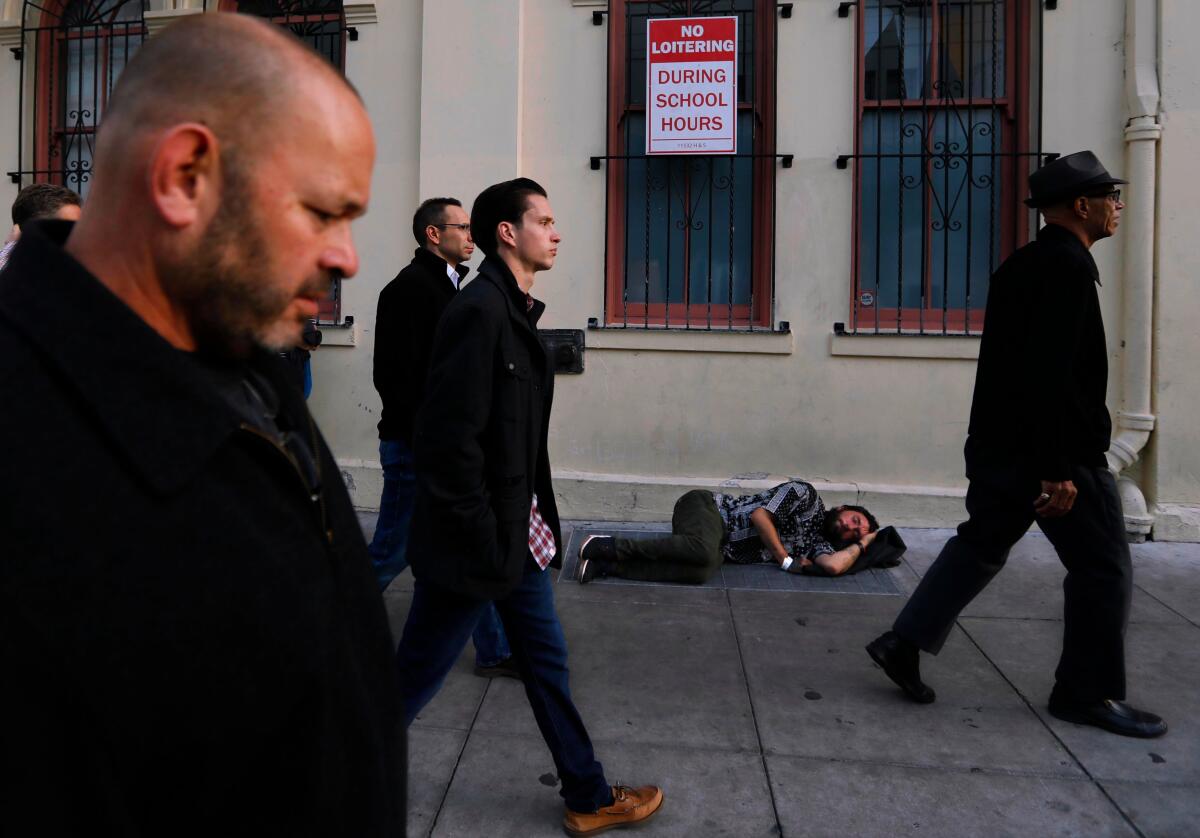

Wage inequality has risen more in California cities than in the metropolitan areas of any other state, with seven of the nation’s 15 most unequal cities located in the Golden State.

San Jose, with its concentration of Silicon Valley technology jobs, had the largest gap of any California metro area between those at the top of the pay scale and those at the bottom. It ranked second in the nation after the suburb of Fairfield, Conn., home to wealthy New York financiers, according to a new analysis of 2015 U.S. Census data by Federal Reserve economists. San Francisco and Los Angeles also ranked high on the list.

More surprising, perhaps, is the inclusion of Bakersfield, where high-wage engineering jobs are juxtaposed with poverty-wage farm work.

The heavy concentration of California metro areas is a striking turnabout from 1980, when just three figured in the top 15.

As inequality has soared across the United States, most sharply since the 1980s, it has been the focus of widespread debate and become a hot political issue. But less attention has focused on dramatic geographical differences in inequality.

“Wage inequality … has risen quite sharply in some parts of the country, while it has been much more subdued in other places,” wrote Jaison Abel and Richard Deitz, economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, who titled their report, “Why Are Some Places So Much More Unequal than Others?”

“Rising inequality in the United States has largely been an urban phenomenon,” they added.

Large cities with dynamic economies tend to have higher wage disparities, while midsized cities with “sluggish economies” are less unequal because they attract fewer high-wage workers, the authors found.

Nationally, outsized executive pay has become a major issue. Under President Obama, the federal Securities and Exchange Commission ordered corporations to publicly report the ratio between what top executives are paid and what their median workers earn, drawing attention to big compensation packages. But the new tax law backed by President Trump and congressional Republicans cut income taxes for top earners.

The new Federal Reserve study only addresses wages and does not examine growing disparities in assets such as real estate and stocks, the focus of recent calls by progressive politicians to impose a wealth tax on the rich.

U.S. wages have grown “much more rapidly for highly skilled workers at the top of the wage distribution than for those in the middle or at the bottom,” the authors wrote. “A worker in the 95th percentile of the wage distribution earns more than three times what the median worker earns and more than seven times the earnings of a worker at the 10th percentile, well above what these ratios were just a few decades ago.”

Comparing wage data from 1980 to 2015 in 200 metropolitan areas, Abel and Deitz documented a disproportionate rise in inequality in the most populous cities, like Los Angeles, New York and Houston. By contrast, the pay gap has remained largely flat in midsized Midwestern and Southern cities, such as Wasau, Wisc., Fort Wayne, Ind., and Ocala, Fla.

The report focused on what the authors call the 90/10 ratio: the difference between the earnings of workers in the 90th percentile of wage distribution and those in the 10th percentile. But the disparities were reflected throughout pay levels.

“In 1980, there was virtually no relationship between city size and the level of wage inequality,” according to the report. “None of the 10 largest metropolitan areas ranked among the nation’s most unequal places.… By 2015, five of the 10 largest areas ranked among the most unequal in the country.”

In San Francisco, inflation-adjusted wages grew by 18% between 1980 and 2015 for the bottom 10% of the workforce. For those paid at the median — with half of wage earners making less and half making more — pay rose by 53%. And for those at the top, earning in the 95th percentile, pay rose a whopping 122%, according to the paper.

In Los Angeles, over the same 35 years, inflation-adjusted pay rose by just 3% for those in the bottom 10%, and by 18% for those at the median wage. For workers at the top, earning in the 95th percentile, pay rose by 69%.

Ranking 200 metro areas by pay disparities over time, Abel and Dietz found that San Francisco skyrocketed from 128th most unequal in 1980 to eighth in 2015. Over the same period, San Jose jumped from 70th to second and Los Angeles rose from 26th to 12th most unequal.

If the explosive inequality in the Bay Area is easily attributable to a massive expansion of high-paid tech jobs, the fact that Bakersfield ranked in the top tier for unequal pay in both 1980 (12th) and in 2015 (fourth) may be less obvious.

Cal State Bakersfield economist Richard Gearhart said inequality is pronounced in the city of 380,000 people because it has “a highly segmented labor market — either really well paying or really poorly paying. We don’t have a flourishing ‘middle-class’ economy for IT, managers, and finance.”

With robust oil and agriculture industries, the city has six-figure engineering and science jobs. But it also has some 40,000 local farmworkers, many of whom are paid on a piece rate, earning below the legal minimum wage, Gearhart added.

As for Los Angeles, Christopher Thornberg, a partner at the consultancy Beacon Economics, said the city has “high-income folks in entertainment and some in tech. But it also has an enormous low-skilled population working in restaurants, hotels, janitorial services and back offices.”

The fact that Los Angeles rose in the inequality ranking over 35 years can be partly attributed to “a huge influx of low-skilled Latin Americans into L.A. County since 1980,” he said. Moreover, he added, “L.A. was once an enormous manufacturing center. But since 1990, manufacturing jobs have dropped from about 850,000 to 350,000.”

According to the Federal Reserve study, growing inequality in large cities is driven by the contrast between rapidly rising wages of the best-paid workers, and far more modest increases for medium- and low-wage workers.

Several factors explain the trend, the report indicates:

- Big cities have more need for skilled workers. Think programmers in San Jose and San Francisco, and finance executives in New York. On the other hand, as automation and globalization have cut the demand for middle- and low-skilled workers, cities such as Detroit and Youngstown, Ohio, where thousands of auto and steel industry jobs disappeared, experienced wage stagnation.

- What economists call “urban agglomeration economies” — the way that companies in related businesses cluster together in dense metropolitan areas — spurs higher productivity and higher wages. This clustering tends to favor higher-skilled workers, research shows. Think Hollywood.

- The weakening of labor unions led to less worker bargaining power to create middle-class jobs. And the erosion in the inflation-adjusted value of the federal minimum wage over decades has kept pay low for those in the bottom tier, although many states are now raising pay floors.

- Migration within the U.S. is changing the employment mix, with better-skilled professionals moving to cities to earn more. “Since the early 1980s, those with college and graduate degrees have flocked to large cities, while lesser-skilled workers have increasingly been priced out of such places, in large part because of high and rising housing costs,” the authors write.

In California, the migration trend has been pronounced. The state attracts a steady stream of college graduates, especially from the East Coast, even as many less-educated residents move to neighboring states — and to Texas — in search of a lower cost of living.

In 2017, according to the latest U.S. Census migration data, the Golden State lost a net 86,890 residents without bachelor’s degrees, and just 4,443 with four-year degrees. It gained 11,653 people with graduate degrees.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.