Column: Billionaires emerge as the defining campaign issue for 2020

With the 2020 presidential campaign in full swing, it is clear that the defining issue of the election will be economic inequality — and that puts America’s billionaires in the dock.

Proposals for a tax on extreme wealth have been put on the table by Democratic candidates Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, eliciting responses of varying vehemence from the billionaires lobby.

These responses, as we’ve reported, have been mostly negative, although here and there a few billionaires have allowed that, yes, they may have too much money and it might be good public policy to redistribute some of it through taxation.

If the rich have to pay a percentage of their wealth in taxes each year, it makes it harder for them to maintain or grow their wealth.

— Saez and Zucman, UC Berkeley

The wealth tax proposals are part of a general attack on economic inequality that all the Democratic candidates share, to some extent.

“The middle class is getting killed,” former Vice President Joe Biden said during the Dec. 19 Democratic debate. “The middle class is getting crushed. And the working class has no way up as a consequence of that.... The idea that we’re growing — we’re not growing. The wealthy, very wealthy, are growing. Ordinary people are not growing. They are not happy with where they are.”

Even the two certified billionaires in the Democratic race have expressed support for raising taxes on the ultra-wealthy. “I’ve been for a wealth tax for over a year,” Tom Steyer said during the debate. Michael R. Bloomberg, who did not appear at the debate, said at a campaign event in Phoenix three weeks ago that while a wealth tax of the variety proposed by Warren or Sanders “just doesn’t work,” he supports “taxing wealthy people like me.”

Sanders has proposed a graduated tax on net worth starting at 1% on wealth above $32 million for a married couple, rising in steps to 8% on wealth over $10 billion. (For singles the thresholds would be halved.) Warren’s tax would begin at 2% a year on household net worth over $50 million, with an additional 4% surcharge on wealth over $1 billion.

Both proposals would raise trillions of dollars over a decade. Both are also designed explicitly to break up big family hoards. Sanders says that under his plan, “the wealth of billionaires would be cut in half over 15 years which would substantially break up the concentration of wealth and power of this small privileged class.”

Two billionaires explain why they think they know better how to spend their money than you do.

And in the words of Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, the UC Berkeley economists who are advisors to Warren on her wealth tax plan, “if the rich have to pay a percentage of their wealth in taxes each year, it makes it harder for them to maintain or grow their wealth.”

On the other side of the debate are commentators such as Erskine Bowles, a White House chief of staff under Bill Clinton, and Henry Paulson, a Treasury secretary under George W. Bush, who called the wealth tax proposals “wishful thinking” in a recent op-ed and lumped them together with proposals such as universal healthcare (“Medicare for all”) as policies that are “fundamentally misguided and would result in economically harmful outcomes that could put our economy on an unstable and precarious path.”

Billionaires have been speaking for themselves, too. In October, money manager Leon Cooperman erupted to Politico about Warren’s plan: “This is the [blankety-blank] American dream she’s [blankety-blanking] on,” he said, using slightly more descriptive language.

A couple of weeks later, Jamie Dimon, the chairman and CEO of JPMorgan Chase, groused on CNBC that Warren “uses some pretty harsh words ... some would say vilifies successful people.”

For all their dudgeon, Cooperman and Dimon were rather more measured than the late billionaire Silicon Valley venture investor Thomas Perkins, who in 2014 sought in a letter to the Wall Street Journal to “call attention to the parallels of fascist Nazi Germany to its war on its ‘one percent,’ namely its Jews, to the progressive war on the American one percent, namely the ‘rich.’”

It’s proper to note that more than 200 of the world’s wealthiest individuals and families have signed on to the “Giving Pledge” created by Bill Gates and Warren Buffett, a commitment to donate a majority of their wealth to philanthropic causes. The signers include Michele B. Chan and Patrick Soon-Shiong, the owner of The Times.

Whether such charity solves the social and economic problems of extreme wealth concentration is debatable, however, since the choice of how to distribute their wealth would remain in the hands of a small number of wealthy persons and underscores the issues raised by how their wealth became so concentrated in the first place.

Even a signer of the pledge has questioned whether it is accomplishing its goals. The pledge is growing “perhaps not as rapidly as we hoped,” stated telecommunications billionaire Leonard Tow in October.

Billionaire Leon Cooper is whining again about proposals to tax the rich. He should get over it.

Skepticism about the extreme wealth disparity isn’t a new phenomenon. Given the passage of time, and social and economic evolution, it’s difficult to pin down how the wealth inequality that has developed in this country compares to that of bygone eras and distant climes. But in 1929, according to historian William E. Leuchtenburg, 36,000 families — the top 0.1% of that era — received as much income as the bottom 12 million households, or 42%.)

The extreme concentration of wealth in the United States in the late 1800s and again in the 1920s were major contributors to recurrent economic slumps and market crashes (once known as “panics”), climaxing with the crash of 1929 and the Great Depression.

Those crises led to two congressional investigations early in the last century, in which lawmakers tried to hold the millionaire nabobs of those eras responsible.

In the first, Democratic Rep. Arsène Pujo of Louisiana put the Wall Street “money trust” on trial in 1912-1913, when the market crash of 1907 was still fresh in Americans’ memories. Pujo’s chief quarry was J. Pierpont Morgan, whose death in 1913 may have been hastened, his doctor reported, by the pitiless interrogation he was subjected to from committee counsel Samuel Untermyer.

With the Great Depression casting its pall over the country in 1933, the Senate Banking Committee again put Wall Street in the dock. This time the star witness, grilled by committee counsel Ferdinand Pecora, was J.P. Morgan Jr. The hearing’s enduring image is that of “Jack” Morgan at the witness table with Lya Graf, a diminutive performer from the Ringling Bros. circus, cradled on his lap, where she had been perched by a circus publicity agent. (Graf was mortified by the scene, but Morgan used it fortuitously to soften his image — “No longer a grasping devil whose greed and ruthlessness had helped bring the nation to near ruin,” as the financial journalist John Brooks would report, “but rather a benign old dodderer.”)

The Morgan enterprise survived — it’s the banking giant now headed by Dimon — though the family’s name remains a potent symbol of plutocracy.

Can anyone really dispute that the level of wealth held by the richest Americans today has reached absurd levels? The wealthiest individual in America, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, is worth $114 billion, according to the 2019 Forbes ranking of the 400 richest Americans. This is a sum that defeats efforts at human comprehension, but let’s try. If Bezos spent $100 million a year on himself, it would take him 1,140 years to spend it all.

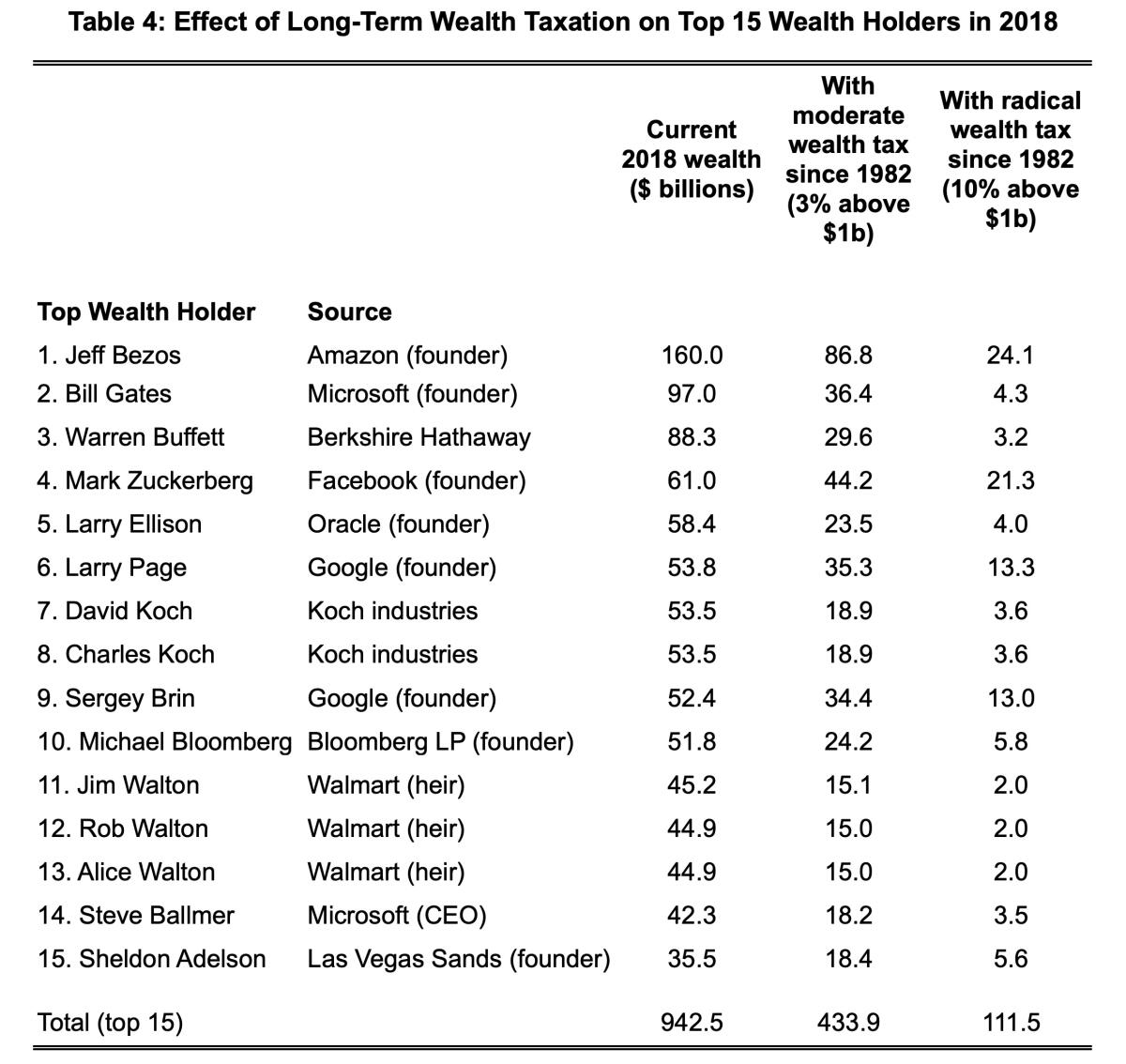

Saez and Zucman calculated what would happen to the Bezos fortune if it had been subject to a 3% annual wealth tax applied to the excess over $1 billion since 1982. It would now be worth $86.8 billion, meaning that his $100-million annual spending would exhaust his nest egg in a mere 868 years. (Saez and Zucman used as their starting point Bezos’ $160-billion fortune in 2018, but he gave his ex-wife Mackenzie a settlement of about $36 billion in their divorce this year.)

One common defense of billionaires is that they’ve earned their wealth through hard work and the discovery of a product or service that brought the world beating a path to their door and therefore a wealth tax is unjust.

But that’s a simplistic view of the billionaire economy. For one thing, it overlooks that virtually no one on the Forbes list got there without the assistance of armies of employees, or that judging from the extreme concentration of the gains from the product or service, many of those employees were not paid the full economic value of their contribution.

Nor does the argument acknowledge that some billionaires reached the list not due to their own hard work and intellect, but that of their forebears or late spouses. The widow of David Koch, who died this year, is in at No. 13 by virtue of her inheritance of a 42% stake in Koch Industries.

Descendants of Walmart founder Sam Walton occupy three of the top 15 slots; two surviving grandchildren of candy maker Frank Mars (and children of his son Forrest Mars Sr., who made the family company a global force) share No. 19. Mackenzie Bezos is at No. 15.

Some of these heirs may have worked in or even presided over the family enterprise, but in many cases the hard work of building a family fortune was done before their arrival on the scene.

Our emerging political debate over taxing the rich seems to be getting bogged down in details — how high a tax rate, should we tax income or wealth, etc., etc.

The defense of huge fortunes as just deserts evades the question of how much even a successful entrepreneur should retain from his or her effort, or how to measure it against the social utility of the fortune’s source. How should we evaluate Facebook co-founder Mark Zuckerberg’s roughly $69-billion fortune against damage his company is alleged to have done to the democratic process, or its merciless exploitation of personal data for its own profit?

In more general terms, wealth inequality places immense resources in the hands of people unable to spend it productively, and keeps it out of the hands of those who would put it to use instantly, whether on staples or creature comforts that should be within the reach of everyone living in the richest country on Earth.

As Warren stated in defense of her wealth tax during the Dec. 19 debate, “You leave two cents with the billionaires, they’re not eating more pizzas, they’re not buying more cars. We invest that 2% in early childhood education and childcare, that means those babies get top-notch care. It means their mamas can finish their education. It means their mamas and their daddies can take on real jobs, harder jobs, longer hours.”

That brings us to the putative drawbacks of a wealth tax. Some contend that heavy taxation on the income or assets of the affluent will sap them of a willingness to work, depriving the economy of their energy and intellect. Even if that were plausible, it suggests that millionaires and billionaires should be subject to a work requirement before receiving a tax cut, much as conservatives advocate work requirements on low-income Americans seeking coverage from Medicaid.

Critics of the wealth tax proposals argue it would be difficult, even impossible, to fairly value private assets outside established markets, such as fine art and private companies, and that it would prompt widespread asset concealment by billionaires intent on evasion.

Saez and Zucman counter that most nonliquid assets can be valued based on known metrics — reported sales and profits for nonpublic businesses, comparable property appraisals for real estate. Artworks can be evaluated based on their insurance coverage, and in any case account for a relatively small share of billionaires’ wealth.

As for evasion, “tolerating tax evasion is a policy choice,” they observe. Both Warren and Sanders advocate increased funding for the Internal Revenue Service and more stringent standards for auditing big taxpayers.

It may be hard to divine today what form a wealth tax may take, but pressure to bring extremely large fortunes under control is unlikely to ebb.

Among the Democratic candidates, the only real disagreement on economic policy appears to be over how aggressively to go after concentrated and inherited wealth, not whether it’s worth reining in at all. Come the general election, the Democratic candidate will draw a distinction between that viewpoint and the Republican mantra, which is that the economy has been growing overall, so why should anyone — rich, poor or middle class — complain?

Some billionaires evidently perceive that there’s danger for their own wealth and the economy at large in today’s level of inequality.

“America has a moral, ethical and economic responsibility to tax our wealth more,” wrote 20 millionaires and billionaires, including George Soros, heiress Abigail Disney, and venture investor and entrepreneur Nick Hanauer, in an open letter in June. “A wealth tax could help address the climate crisis, improve the economy, improve health outcomes, fairly create opportunity, and strengthen our democratic freedoms.

“Instituting a wealth tax,” they concluded, “is in the interest of our republic.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.