Column: Billionaire objects, profanely, to Elizabeth Warren’s plan to tax billionaires

Leon Cooperman, one of America’s outstanding billionaire crybabies, has launched a public fight with Democratic presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren over her proposal for a wealth tax, thus gifting those who follow the normally dull and dreary debate over fiscal policy with a momentary voyeuristic thrill.

Important issues lie at the core of this fight, so it’s wrong to dismiss it as merely a spat. So we’ll delve beneath the surface. One key question is whether Cooperman, for all his hand-wringing, has a point in critiquing Warren’s proposal. Short answer: He does, but mostly he doesn’t.

But first, here’s the outline of the fight. Warren in January proposed a tax of 2% on net worth above $50 million and another 1% on net worth above $1 billion. When he was asked last month by Politico to comment on Warren’s policies, Cooperman dellivered a profane outburst, stating, “This is the [blankety-blank] American dream she’s [blankety-blanking] on.” Those seeking the quote in its full technicolor glory can find it here.

Let’s elevate the dialogue and find ways to keep this a land of opportunity where hard work, talent and luck are rewarded and everyone gets a fair shot at realizing the American dream.

— Billionaire Leon Cooperman

Warren tweeted back, “Leon, you were able to succeed because of the opportunities this country gave you. Now why don’t you pitch in a bit more so everyone else has a chance at the American dream too?” Cooperman responded with a five-page missive, duly circulated to the press, under the letterhead of his Omega Family Office investment headquarters.

Cooperman’s letter provides lots of material to chew on. Written in a more-in-sorrow-than-in-anger passive aggressive tone, it opens with the gripe that Warren in her tweet had admonished him like “a parent chiding an ungrateful child,” which understandably would get under the skin of a 76-year-old former Goldman Sachs investment banker.

Cooperman proceeds to describe his life as “a classic American success story,” beginning with his upbringing as the son of an emigrant Polish plumber, proceeding to his education in public school and college, and on to his career at Goldman Sachs, his great wealth (he doesn’t say so, but Forbes ranks him 268th among its 400 richest Americans, with a net worth of $3.2 billion), and his devotion to philanthropic causes.

Reading this portion, I was struck with a strong sense of having read all this before. It turns out that my deja vu was warranted, because Cooperman had written it all in a letter he sent to President Barack Obama in 2011, chiding Obama for “your and your minions’ role in setting the tenor of the rancorous debate now roiling us that smacks of what so many have characterized as ‘class warfare.’”

Cooperman asked, “Is the tone of the current debate really constructive?” This resembles Cooperman’s objection, in the new letter, to Warren’s “vilification of the rich.” (As we’ve observed before, such appeals from the mountaintop for “civility” or “constructive criticism” often mask a domineering intent.)

The letter to Warren then proceeds to the gist of their economic disagreement. Let’s take his points in turn.

Cooperman first offers a roster of self-made billionaires who have accumulated their wealth “by providing a product or service that others want or are willing to pay for.” They include Bill Gates, Home Depot founder Arthur Blank and Bernie Marcus, and Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg. He’s right that, to varying degrees, they’ve made contributions to society. But by listing them according to the employment they’ve provided, he seems to be suggesting that giving people jobs is an expression of altruism, as opposed to a necessity for creating a successful business.

He then takes aim at Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, the UC Berkeley economists on whose research into wealth inequality Warren’s tax proposal is based. Cooperman repeats a common criticism that their finding that the U.S. tax system is inherently flat or regressive — that the rich pay as much or less in taxes than the middle-class or poor as a percentage of their income — ignores “transfer payments” that are generally paid to the middle-class or poor.

By Cooperman’s reckoning, these include Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid. But he’s wrong about Social Security, and to a lesser extent Medicare. Social Security isn’t a transfer payment. It’s funded by the recipients’ own contributions over their lifetimes — those born after 1965 have contributed, on average, enough to fully fund their own benefits. Payroll contributions also fund Medicare, which also charges premiums.

Wall Street Democrats’ fear of Elizabeth Warren reminds us that they opposed the New Deal too.

Cooperman acknowledges that state and local sales taxes are indeed regressive, falling more heavily at the lower end of the income scale. But he waves away that point, asserting that they “have nothing to do with federal fiscal policy and tax code structure.” But that’s nonsense. States and localities have had to raise sales taxes in part because federal budget-cutting has pushed expenses down to them.

The federal tax cuts enacted by Republicans in December 2017, moreover, put pressure on state and local tax structures by limiting their deductibility on federal taxes — a case in which federal tax code structure has a direct impact on state and local taxes, especially in states such as California and New York (where Cooperman pays at least some of his local taxes).

Cooperman further asserts that Saez and Zucman ignore taxes on the “future dividends, interest and capital gains earned on savings,” which leads them to “understate taxes on the rich.” This is pure sleight of hand. As Ed Kleinbard, the ace tax professor at USC, has pointed out, the tax on capital gains is America’s only voluntary tax — it isn’t paid until the underlying assets are sold, and if they’re held until the owner’s death, the tax is extinguished for his or her heirs. Cooperman even acknowledges this feature further down in his letter, and even advocates its repeal. Dividends, though they’re taxed the year of issuance, receive a lower tax rate than wages.

The letter then disputes the notion that the wealthy aren’t paying their fair share of taxes. We hear these statistics all the time: The top 1% of taxpayers pay a greater share of federal income taxes, (37.3%) than the bottom 90% combined (30.5%), the top 50% of taxpayers accounted for 97% of all individual income taxes, etc., etc.

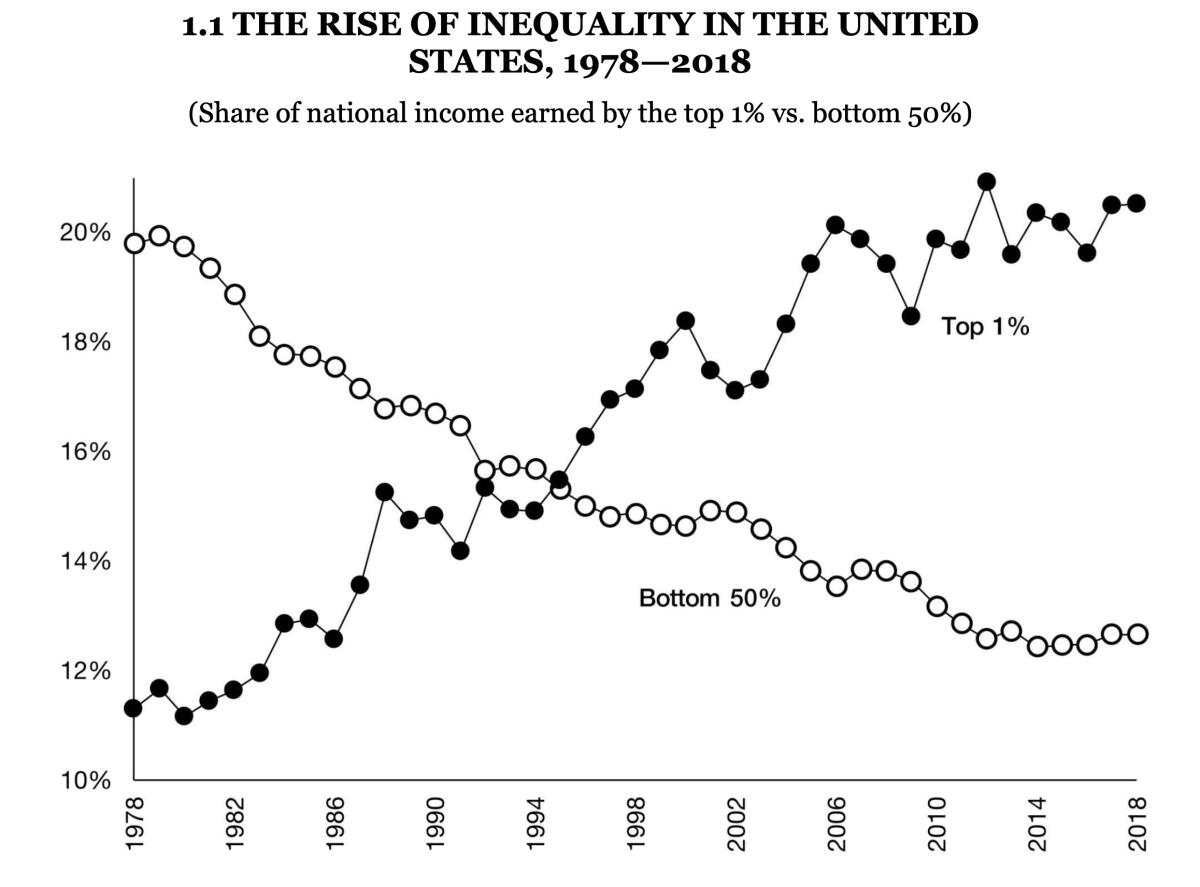

He’s right that the wealthy pay the most income tax. But what Cooperman doesn’t mention is the extreme imbalances in income and wealth that account for much of the imbalance in tax liability. The top 1% earned more than 20% of all national income in 2018; the bottom half only about 12%. As Isabel V. Sawhill and Christopher Pulliam of the Brookings Institution have reported, America’s top 20% held 77% of total household wealth in 2016, more than three times the holdings of the middle class, defined as households in the 20%-80% economic segments

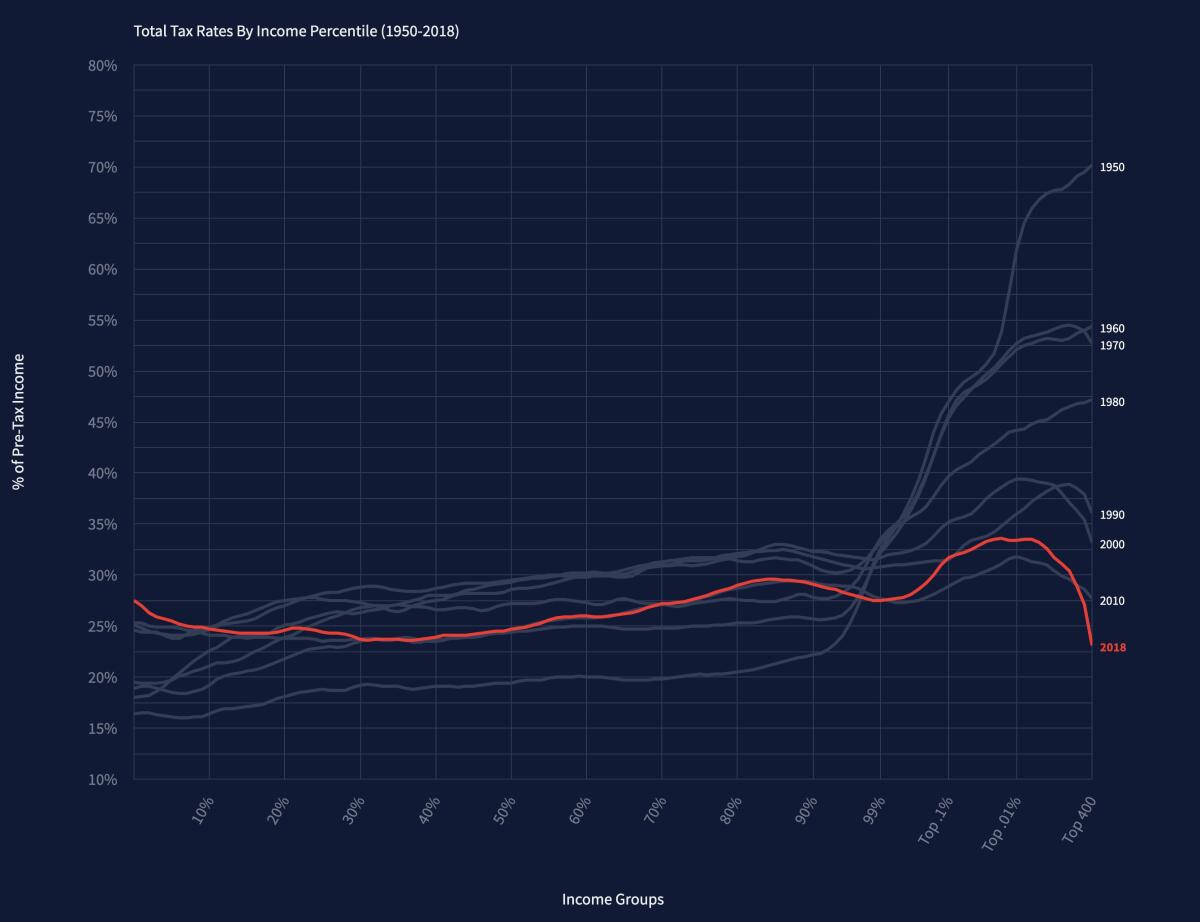

Another factor Cooperman ignores — and perhaps the most important factor — is that tax rates on the rich have come sharply down over time. According to calculations by Saez and Zucman, the average tax rate on the top 0.01% of income earners (those with income of more than about $8 million today) was more than 67% in 1950. Today it’s about 33%. The average rate on the top 400 was 70% in 1950 and about 23% today.

Two billionaires explain why they think they know better how to spend their money than you do.

Cooperman glides over this fact — indeed, in his letter to Warren he doesn’t mention even once the 2017 tax cut, which was aimed chiefly at wealthy taxpayers like himself. Given that Warren’s wealth tax is manifestly designed to shift the burden back, this is an odd, and telling, omission.

Professing himself to be at heart a supporter of progressive taxation, Cooperman says the key flaw of the wealth tax is that it’s unworkable, “plagued by issues of constitutionality, tax avoidance, asset valuation, and administrablilty.”

One should be wary of arguments against a reform based on its impossibility, even before the legislative process begins. Lots of reforms once thought to be impossible turned out to be anything but — think of gay marriage and healthcare reform, just for starters. Cooperman points out that many European countries that tried wealth taxes ended up abandoning them, which is true, but he doesn’t mention that they typically were abandoned by conservative political regimes, which won’t be a label easily attached to a Warren presidency.

The beating heart of Cooperman’s argument is that, though the rich should pay more than middle- or low-earners, they’re already there. “At some point,” he writes, “higher effective ... rates become confiscatory.” That may be so, but there’s no evidence we’re anywhere near that now. Quite the contrary, given how far average and marginal tax rates on the wealthy have fallen over the last 50 or 60 years.

“I don’t mind working six months of the year for the government and six months for myself,” he writes, “paying an effective combined tax rate of 50% on my income.” Who’s this “government” of which our Lord Bountiful speaks? It’s you and me, and our children, and everyone who depends on government services for their health, support, safety and livelihoods. Portraying “government” as some faceless other is nothing but a cynical dodge aimed at concealing that it’s an entity that represents all the people and has been increasingly indulgent toward those of Cooperman’s income sector during his entire career.

Cooperman’s assertion that he’s already paying his share reminds me of my favorite take on progressive taxation, by the conservative economist Herbert Stein. I’ve cited it often, but it never gets old: “Whatever is the existing degree of progression,” Stein wrote, “people who pay the top rate will think it is too much.”

Cooperman makes much of his charitable giving, stating that he intends to donate substantially all of his fortune to charity upon his death. But that evades the question of why the disposition of his wealth should be his subject to his desires or whims. Who’s to say that they would correspond to the real needs of society?

This is the fundamental issue raised by Warren’s wealth tax proposal — how wealth is distributed across society and how it should be used. Despite Cooperman’s closing plea to Warren — “Let’s elevate the dialogue and find ways to keep this a land of opportunity where hard work, talent and luck are rewarded and everyone gets a fair shot at realizing the American dream” — that’s the issue he never gets around to facing.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.