When 69-year-old Marietta Jinde died in September 2016, police had already been called to her home several times because of reports of possible abuse. A detective described conditions at the woman’s home in Gardena as “horrendous.”

She was so emaciated and frail that the hospital asked Los Angeles County adult protective services officials to look into her death.

Yet by the time a coroner’s investigator was able to examine Jinde’s 70-pound body, the bones from her legs and arms were gone. Also missing were large patches of skin from her back. With permission from county officials and saying they did not know of the abuse allegations, employees from OneLegacy, a Southern California human tissue procurement company, had gained access to the body, taking parts that could have provided crucial evidence.

Coroner officials said police did not inform them of the possible abuse complaints until 10 days after Jinde died. They said they were able to complete their investigation by using the autopsy exam, hospital records and photos, and determined that she died of natural causes, including severe heart disease.

After reviewing the autopsy report, Cyril Wecht, a forensic pathologist who has consulted on many prominent death investigations, questioned the coroner’s ability to make that determination when the bones and skin had already been removed.

“We can’t be sure the bones weren’t fractured,” Wecht said. “This could have been a manslaughter case.”

The case is one of dozens of death investigations across the country, including more than two dozen in Los Angeles and San Diego counties, that The Times found were complicated or upended when transplantable body parts were taken before a coroner’s autopsy was performed.

In multiple cases, coroners have had to guess at the cause of death. Wrongful-death and medical malpractice lawsuits have been thwarted by early tissue harvesting. A death after a fight with police remains unsettled. The procurement process caused changes to bodies that medical examiners mistook as injuries or abuse. In at least one case, a murder charge was dropped.

Organ procurement before an investigation has long been legal, provided the coroner agreed. The motivation was to increase the number of hearts, kidneys and other vital organs needed to extend the lives of Americans waiting for transplants. To raise those numbers, California and other states over the last decade passed laws requiring coroners and medical examiners to “cooperate” with the companies to “maximize” the number of organs and tissues taken for transplant. Procurement companies’ lobbyists helped to write the legislation and push it into law.

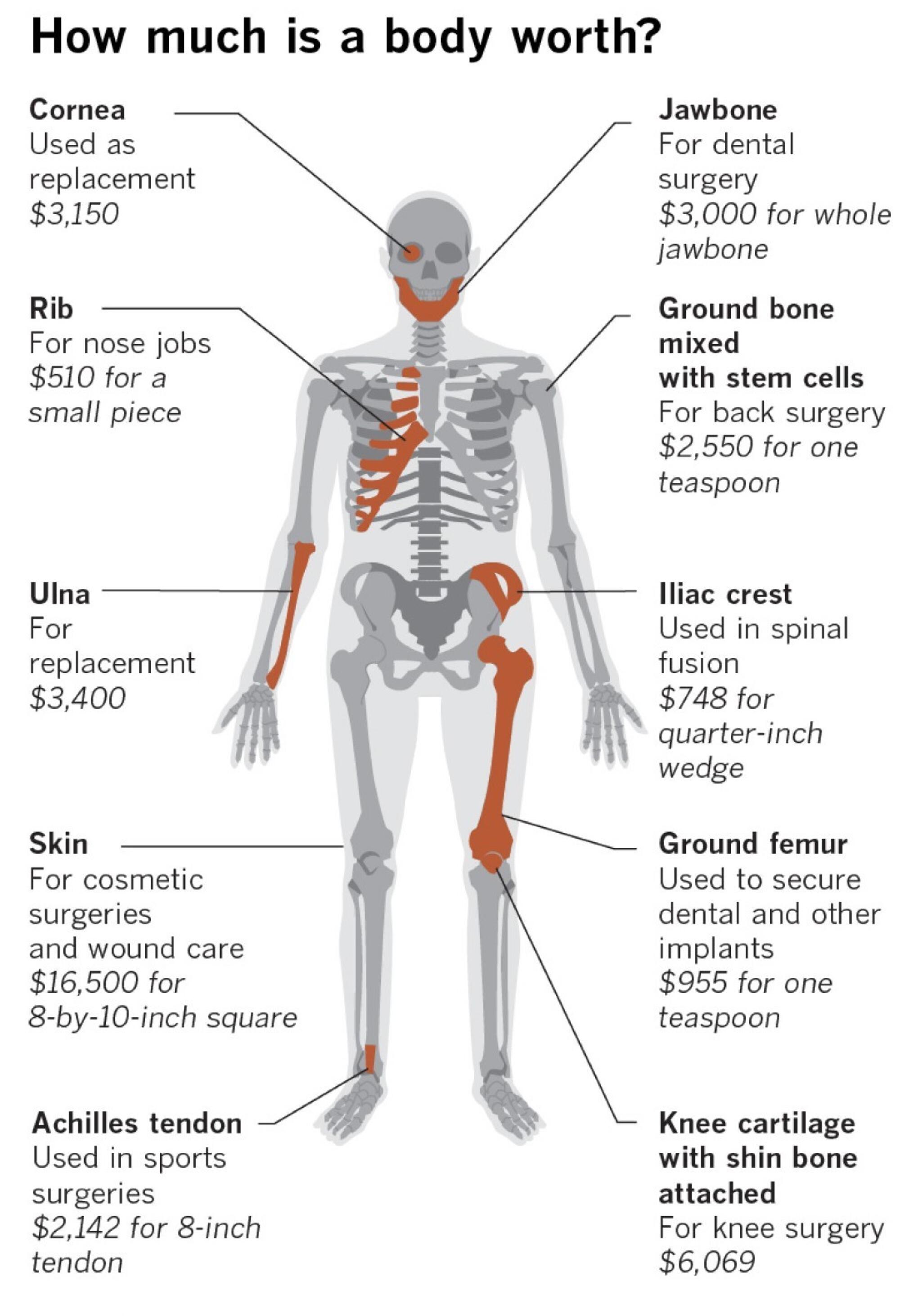

In a handful of states the laws go even further, giving the companies the power to force coroners to delay autopsies until they have harvested the body parts.

Although the companies have emphasized organ transplants, in far more cases nationwide they harvested skin, bone, fat, ligaments and other tissues that are generally not used for life-threatening conditions. Those body parts fuel a booming industrial biotech market in which a half-teaspoon of ground-up human skin is priced at $434. That product is one of those used in cosmetic surgery to plump lips and posteriors, fill cellulite dimples and enhance penises. A single body can supply raw materials for products that sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars.

In lobbying for the laws, the companies pointed to papers published in professional journals stating categorically that there has never been a single documented instance of body-part procurement interfering with a death investigation.

But the papers’ authors included procurement company executives and others with undisclosed ties to the industry. And the source of the claim was a short article in a 1994 American Bar Assn. newsletter, which did not even discuss the donation of bone and other tissues.

The expanded reach of the procurement industry has troubled some death investigators.

Melissa Baker, a former investigator in the medical examiner’s office in Pierce County, Wash., filed a whistleblower complaint in 2015 after three procurement companies moved into that county’s morgue to access cadavers.

“One of my biggest concerns … was the mere fact that someone could potentially get away with murder because evidence has been bungled, lost or not collected,” she said.

An independent review of Baker’s complaint found evidence was lost in a homicide case when the procurement team washed the victim’s hands. Yet it found no other “evidentiary problems.” It said Thomas Clark, the Pierce County medical examiner, was following state law by cooperating with the companies so that parts could be removed without affecting his autopsies.

“No death investigation system is perfect,” Clark told The Times. “Even in a system without any relationship to a donation agency there’s a chance that somebody could be inappropriately convicted.… There’s also a chance somebody is going free. I don’t think that chance changes at all with donation.”

When someone dies unexpectedly, responsibility for determining the cause falls to the coroner, according to California law. At a minimum, a coroner’s investigator must view the body and determine whether there are signs of trauma or foul play, according to rules posted on the L.A. County website. But county records show that can be impossible when bones or skin are missing at the time of that exam.

“Body was viewed at the [mortuary] and it was noted that it had been harvested which prevented any further observations,” an L.A. County coroner’s office investigator wrote after Santiago Guimary Jr., 58, of Long Beach collapsed at a bowling alley in 2008 and died shortly after.

In the case of Guimary, Jinde and other Los Angeles deaths, executives at OneLegacy said they had followed the law by obtaining authorization from medical examiners before recovering tissue. Tom Mone, the company’s chief executive, told The Times OneLegacy has received “no references to problems with autopsies” from coroners and medical examiners it works with.

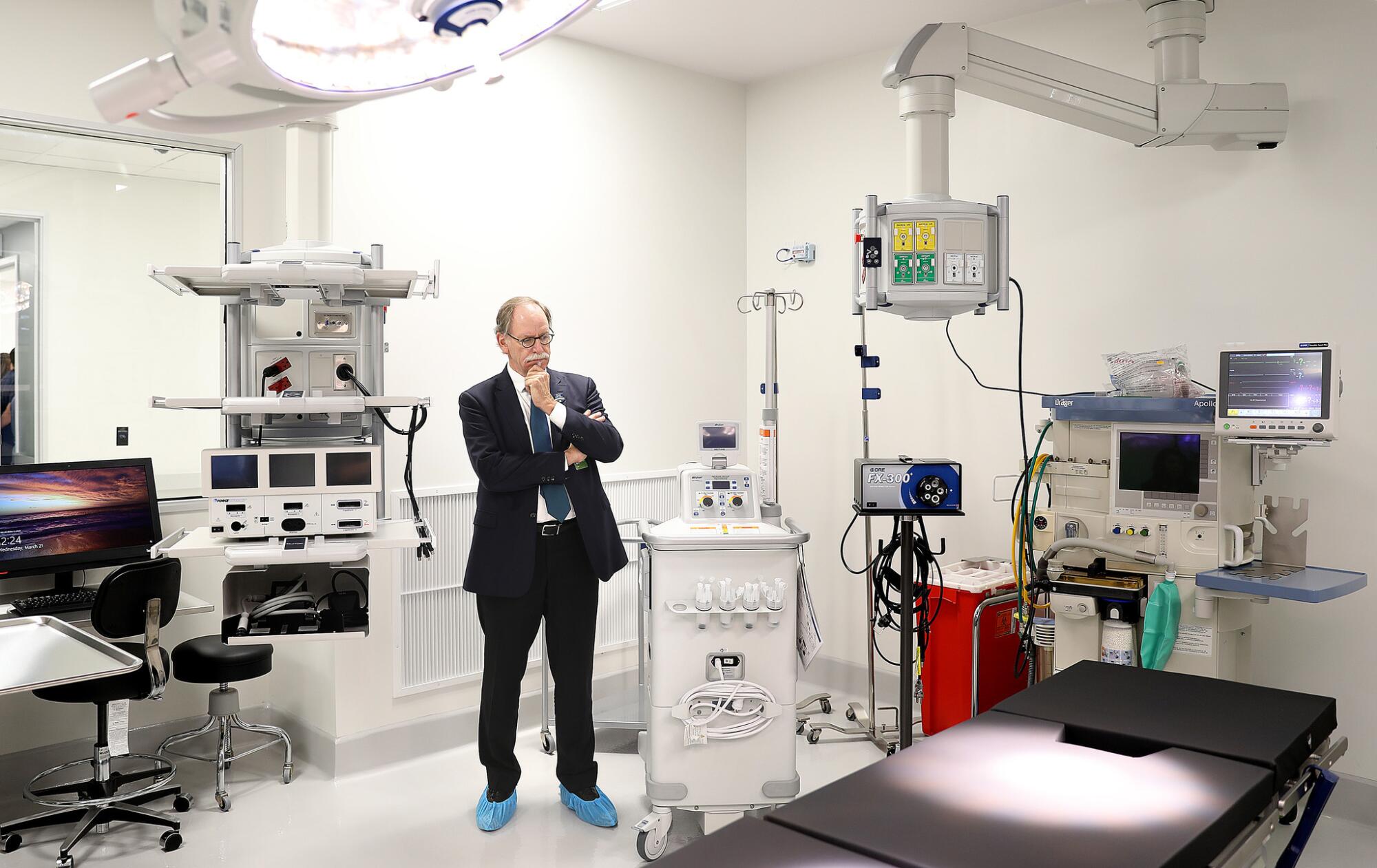

Jonathan Lucas, L.A. County’s chief medical examiner-coroner, said he believed his office’s pathologists had been able to use hospital records and other evidence to answer questions left by the procurement of tissues or organs. He said that, in the opinion of him and his staff, no criminal investigation or cause-of-death finding had been impeded. He added that the autopsies met his office’s “protocol and the statutory requirements.”

The county’s contract with OneLegacy does contain restrictions. Procurements from victims of suspected child abuse and officer-involved homicides must be approved by a senior morgue official.

Another notable contract exception: Donation is “generally unsuitable” in cases of media interest, including celebrity deaths.

Jonn Flath, 18, who had been a varsity athlete in high school, sat down and died in 2011 while working out with cadets in the Air Force ROTC program. Because the teen had signed up to be an organ and tissue donor, the family could not stop the procurement.

His father, Mark Flath of Agua Dulce, said he pleaded with OneLegacy not to take tissues from the body before the coroner had performed an autopsy. OneLegacy took bones and other tissues, including his son’s heart for its valves, which are sold as medical devices. The L.A. County coroner later could not determine why the teen had died.

“You can’t begin to imagine what it’s like to learn that they can’t complete the autopsy because they took your son’s heart,” Mark Flath said.

Flath later sued the coroner and OneLegacy, saying a deputy medical examiner had told him the county made a mistake in allowing the company to harvest his son’s heart. But his lawyer withdrew from the case, Flath said, after learning that state law protects coroners and procurement companies from lawsuits except in cases of extreme wrongdoing. Flath tried to continue the case without a lawyer, but eventually a judge granted the county’s request that it be dismissed.

Lucas, the chief medical examiner-coroner, said his office had received an assessment of the teen’s heart by a pathologist employed by the company that processed and sold the valves. Procurement companies have assured death investigators their cardiac exams are more thorough than what coroners can do on their own.

After the company shipped what remained of the teen’s heart back to the morgue, two other specialists also examined it, Lucas said. It’s uncommon but possible for someone with “a normal appearing heart” to die of a fatal cardiac arrhythmia, he said.

Even if a company has its pathologist examine the heart’s remains for coroners — a now common practice — the review will exclude crucial areas that are sliced off with the valves, Ann Bucholtz, the former Ventura County medical examiner, warns in her book on forensic science. A 2007 study detailed how the companies’ exam after the valves have been removed cannot find several conditions, including abnormalities causing arrhythmias linked to 3% of sudden cardiac deaths.

“The real cause of death,” Bucholtz wrote, can be missed.

Moving into the county morgue

In 2007, the year the laws passed in California and many other states, the procurement companies obtained just 2% of donors of bone, skin or other tissues through referrals by coroners and medical examiners, according to a survey by the American Assn. of Tissue Banks. Now, some companies report that a majority of their donors come from those being wheeled into the county morgue.

Mone, the CEO of OneLegacy, which operates in seven Southern California counties, said about 63% of organ donors and 51% of tissue donors came from the company’s partnerships with morgues in 2017.

“The law,” he said, “has been very beneficial.”

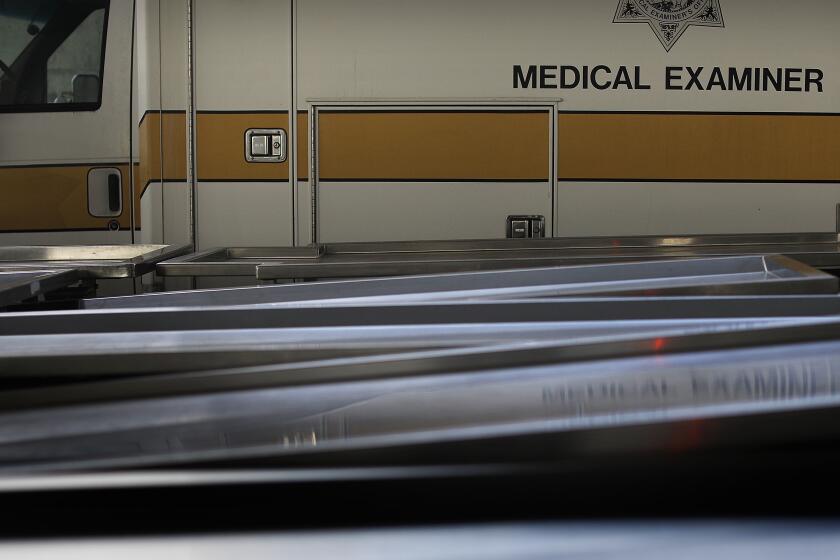

Although the numbers have risen, the cases still amount to a small fraction of the total coroners investigate each year. In the L.A. County morgue, where scores of toe-tagged bodies wrapped in plastic are stacked on metal shelves, there were 140 organ donors and 376 tissue donors in 2013, amounting to about 6% of deaths investigated that year.

To increase the supply of harvested body parts, the companies have embedded procurement teams inside government morgues across the country.

Morgue officials at times give the corporate employees key cards so they can enter at any hour. The companies rent rooms inside the morgues, including suites where surgical teams harvest donors’ tissues.

In a growing number of counties nationwide, the companies can log into government computer files on the newly deceased, allowing them to swiftly find potential candidates for procurement.

In Michigan, a company called Gift of Life said donations of bone and other tissues soared after its foundation gave some coroner offices iPads loaded with special software to record details of a death at the scene, which are transmitted instantly to the company.

For several decades, federal rules have required hospitals to alert procurement companies when anyone dies inside their walls. With the new connections to government morgue computers, the companies also know immediately about deaths outside hospitals — and have contacted families when the body of a loved one is still at the scene, according to written complaints made to supervisors by morgue staff in Los Angeles and Tacoma, Wash.

“I was inside the residence performing my investigation and the family was standing by outside,” Kim Pavek, an L.A. County coroner investigator, wrote in an internal complaint about OneLegacy after a suicide in 2008. “The decedent’s mother asked me why someone from my office would call her cellphone during such a distraught time.... She explained to me that someone from OneLegacy said they were a representative from the coroner’s office inquiring about ‘donating parts.’ ”

The companies say they must move quickly before tissue becomes unusable, and that they train staff to be compassionate.

Anthony Maldonado, a OneLegacy executive, said the company’s employees would never present themselves as working for the coroner.

Companies aid in autopsy work

The companies — and many coroners and medical examiners who have partnered with them — say tissues and organs can be procured with no harm to the death investigation when the two sides work closely together. Companies say their employees can take photos of the bodies and the harvested organs. And they offer to have their employees testify at trials about the body’s condition.

The companies also have agreed to quickly alert coroners when they find unexpected injuries or signs of abuse and then document what they find for use by investigators.

“If there’s something they encounter that they don’t know what to do about, they stop and call us and we tell them that they can either proceed or that they can’t proceed,” said Clark, the medical examiner in Pierce County, Wash.

One result is that many coroners increasingly depend on procurement teams — who have little if any professional training in forensic investigation — to gather crucial evidence, even in possible homicides. In a handbook issued in October 2018, the American Assn. of Tissue Banks noted that “national guidance or training material” on preserving evidence in a death investigation “has not been developed for the donation community.” The handbook instructed how to document and maintain evidence.

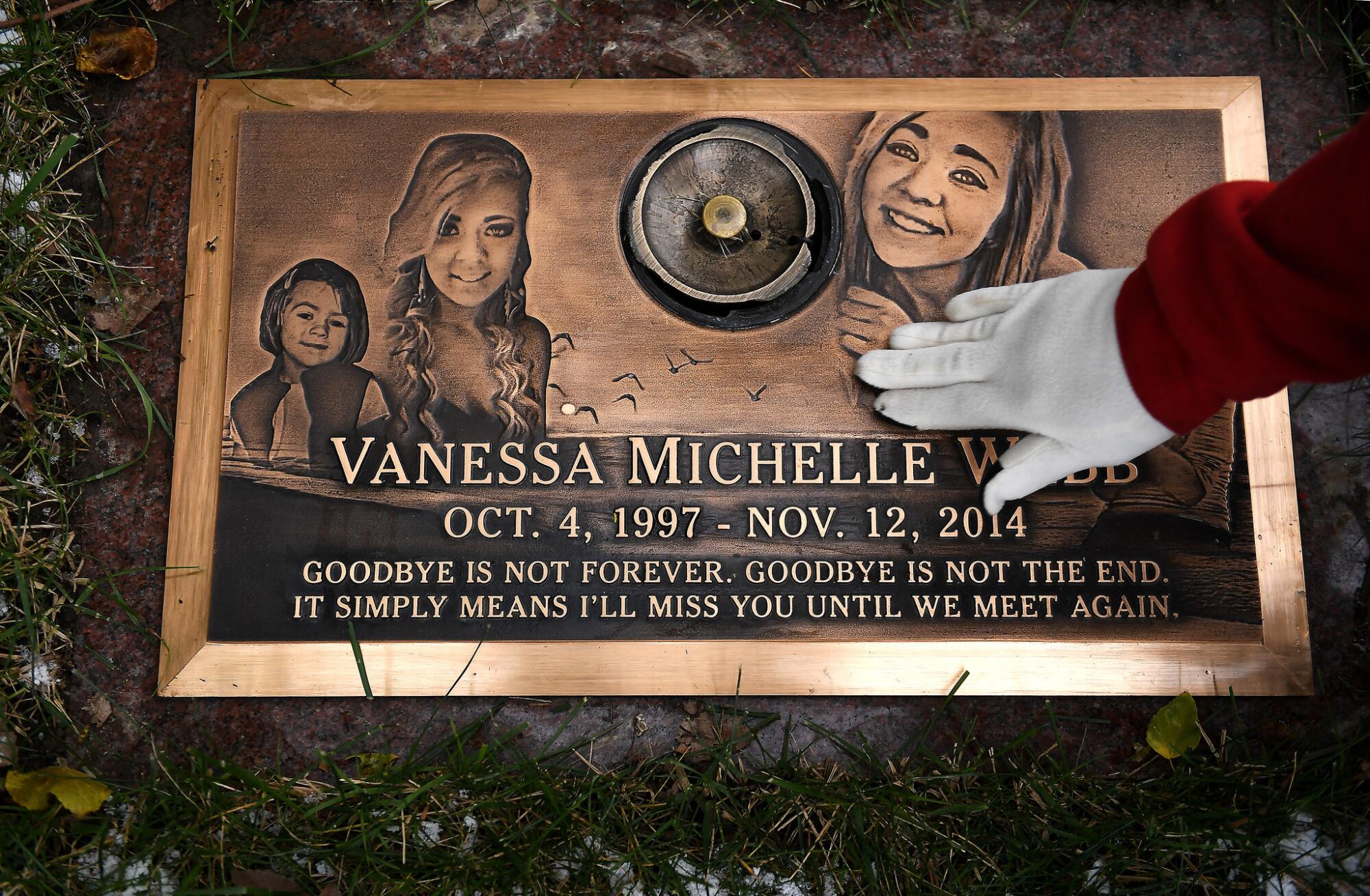

In Ohio, Lorain County Chief Deputy Coroner Frank Miller said in a 2017 deposition that he regularly relies on information from surgical technicians at Lifebanc, a procurement company, to help prepare his autopsy reports. The deposition was taken in a lawsuit filed by the family of 17-year-old Vanessa Webb, who had died unexpectedly. Vanessa’s mother had given Lifebanc permission to harvest her organs before the autopsy — under pressure from the company and the coroner, she says. Miller could not determine why the healthy teen had died.

“This is what we’re always on Lifebanc about — are there clots, is there blood, is there an accumulation of blood, is there anything else unusual,” Miller said in the deposition. “So they know to look for it, and they’ll preserve it if they find it.”

Miller said he was able to do a full autopsy with aid from the procurement companies. A Lorain County lawyer said the government couldn’t comment on the litigation, which is still pending. A lawyer for Lifebanc said the group disputes the lawsuit’s allegations.

In another deposition, Robert Rolley, a former Lifebanc employee who harvested Webb’s tissue, explained how Miller, the chief deputy coroner, had called him during the procurement for descriptions of the lungs and heart.

“I was on the phone with him, somebody was holding the phone to my ear as I was looking in the chest,” Rolley recounted.

Rolley said he told Miller he wasn’t a pathologist and didn’t want to be held accountable. Asked by the lawyer whether he felt he had been appointed an assistant coroner, Rolley replied, “That’s kind of the unfortunate position I was put in.”

Damaged investigations in Southern California

A body is the primary evidence in a death investigation, and protecting it from being contaminated is so crucial in sensitive cases that families aren’t allowed to touch it, according to written procedures at the L.A. County coroner. If there is a potential criminal investigation, families are discouraged from even seeing the body. “The body should not be disturbed in any fashion,” the guide states.

Meeting those guidelines can be difficult when the deceased becomes a donor.

To determine the effect of the companies’ work inside Southern California morgues, The Times reviewed thousands of digital death records obtained from medical examiners in L.A. and San Diego counties to identify those mentioning procurements and obtained the autopsy reports, some dating from the early 2000s.

Neither county would provide a complete list of those deaths. Three other large California counties also refused to provide that information. At least two — Los Angeles and Sacramento — made that decision after discussing The Times’ requests for documents with the procurement companies.

Despite the limited review, The Times found more than two dozen cases in which the procurements made it harder to determine the cause of death. In many of those cases, coroners were unable to conclude either why or how the person died.

The cases included possible homicides, highway accidents, deaths after surgeries, a drug overdose, a suspected suicide and a death that followed a fight with a police officer. The deceased ranged from homeless people to members of wealthy families, although more were poor than rich. Most were middle-age or younger. One was a child.

In at least five cases, the documents show that companies harvested body parts without reporting what appeared to be a death from a crime, an accident or suicide to coroner officials. California law requires any person in charge of a body who has knowledge that the death may have been from unnatural causes to immediately alert the coroner.

A crematory employee called the coroner nine days after William Paul Kennedy died in 2012 to report that the cause might have been an auto accident. The coroner found evidence of the crash — multiple rib fractures, as well as bruises on his chest and eyes — even though a procurement team had already taken bones and sections of skin.

It is impossible to know how many other suspicious, violent or accidental deaths have not been reported or investigated as companies hurried to procure organs or tissues before they became unusable for transplant.

Lucas, the L.A. County medical examiner, said his office “cannot control when a death is reported.” Mone, the OneLegacy executive, said the coroner told the company that Kennedy’s death was not a case for its office.

Many forensic experts say organs can be donated with no effect on the autopsy when the cause of a homicide is obvious — such as a gunshot to the head. In those cases, the procurement surgery happens away from the fatal wound.

But Southern California medical examiners have also approved donating organs in possible homicide cases in which the cause of death is not clear.

Guillermo Valencia, 39, was found lying unconscious in an alleyway in East Los Angeles, blood streaming from a 2-inch gash in the back of his head in 2008. His nose was fractured. His left eye was red with blood. Even though deputies were investigating whether someone had beaten him to death, OneLegacy got approval from his family to harvest his organs and tissues.

In the autopsy report, Louis Pena, a deputy medical examiner, detailed how he found internal injuries but could not tell whether they were caused by violence, an accident or by technicians harvesting organs. He also wrote that because the technicians had procured most of the heart’s aorta he could not rule out that Valencia had suffered an aneurysm, possibly causing him to fall and leading to the injuries. That would have cleared the suspicions of foul play.

Pena eventually concluded that Valencia died of blunt-force trauma to his head but said he did not know whether it was a homicide, accident or natural death.

OneLegacy said the coroner had allowed the donation. Lucas, the chief medical-examiner-coroner, said he reviewed the case and believed that Pena’s findings regarding the procurement were “relatively minor” and the donation had not harmed the investigation.

Pena, now a medical examiner in San Francisco, declined to comment.

In San Diego, a brutal beating or accident?

At UC San Diego Medical Center in February 2013, doctors and nurses suspected violence as paramedics wheeled Christy Rettenmund’s battered body into the emergency room. Upon seeing a head wound that had left her unconscious and bruises on her chest, arms and legs, they called police.

The police thought they had a suspect. Just weeks before, her boyfriend had been arrested on suspicion of domestic violence, one of repeated incidents involving the couple. This time her boyfriend’s account of the night had “numerous inconsistencies,” according to a San Diego County medical examiner’s report.

Rettenmund died two days later. Despite the ongoing police investigation, a medical examiner allowed the procurement group Lifesharing to harvest her lungs and kidneys. During the organ recovery, surgeons made an incision down the middle of her chest, where there were multiple large bruises and abrasions, according to the autopsy report.

A county pathologist later ruled Rettenmund died from her head injuries but said he did not know whether it was a homicide or an accident.

Chief Deputy Medical Examiner Steven Campman told The Times that he believed the organ donation had no effect on the autopsy. “She died from head trauma, and we documented that well,” he said.

San Diego Police Lt. William Todd Griffin said his office presented the case as a homicide to the county district attorney’s office. “The D.A. made the decision not to accept this case because the medical examiner could not make a final determination of cause of death — accidental injury v. homicide,” he wrote in an email to The Times. “Therefore there is no homicide case to prosecute.”

Wecht, the forensic pathologist in Pennsylvania, reviewed the case for The Times and raised questions about its handling. He said the medical examiner lost crucial evidence by allowing the organ harvest.

“You don’t know the nature and extent of the injuries, including to the internal organs,” he said. “When you have someone who is suspected to have been beaten, you don’t give permission for organ or tissue donation.”

Campman said medical records and photographs showed no injuries to her organs.

Said her father, Merv Rettenmund, a former Major League Baseball player: “I’ll be driving around and just cry for no reason. You say to yourself, ‘Why would something have to happen like that?’ ”

The boyfriend’s mother said she has no way to contact her son and believes he is now homeless. The Times could not reach him for comment.

‘Anatomic mayhem’ after surgery

When performing autopsies of deaths after abdominal surgery, guidelines say, investigators should examine the surgical site with everything in its original place. That didn’t happen when Lilia Verdugo, 40, died in 2003 after an elective hysterectomy at Sharp Chula Vista Medical Center.

By the time Bethann Schaber, a San Diego County deputy medical examiner, began an autopsy, Verdugo’s abdomen was little more than a shell. Another medical examiner had authorized Lifesharing to harvest her kidneys and liver, but the procurement group took more tissues than agreed.

The autopsy report said Verdugo’s bladder had been cut accidentally, causing her to lose nearly a pint of blood. George Lundberg, a pathologist and former editor in chief of the Journal of the American Medical Assn. who reviewed the report for The Times, said the “anatomic mayhem” caused by procuring organs next to the surgical site made it impossible to tell what connection, if any, the accident had to the death.

Campman, the chief deputy medical examiner, told The Times he believes Schaber’s inability to determine a cause of death was not affected by the donation. Sharp Chula Vista and Lifesharing said they could not comment because of privacy laws. Lifesharing said it does not recover organs without the medical examiner’s permission.

Problems in autopsies of children

Medical examiners say among their hardest decisions is whether to allow companies to recover organs or tissues from bodies of children when there are suspicions of abuse. Crucial evidence can be destroyed as surgeons extract organs. Previous, partially healed injuries to ribs can refracture. Patterned skin injuries — where an object used to abuse the child leaves an identifying mark — can disappear as the surgeon cuts open the chest.

CT scans of the child’s ribs before the procurement surgery can show fractures, but direct examination is often required to determine when the injuries occurred and whether there were multiple episodes of abuse, forensic experts say.

The procurement process can also change the body and lead investigators to mistakenly believe they are seeing evidence of a crime. After brain-death, organ donors are often given high doses of heparin, a blood thinner, which can cause bruises and bleeding that look like inflicted injuries. And when donors are left on ventilators for days, the brain can fall apart, making it look like a child was shaken or abused, said Jan Leestma, a forensic neuropathologist in Chicago.

Such errors can have catastrophic consequences. In Montana in 2015, the parents of Harbor DeWaard, 6, faced a barrage of questions from Gallatin County investigators, asking how their son had suffered a head injury that a medical examiner said had led to his death.

Three months later, another forensic expert reviewed the case and said there was no trauma. The disintegration of the brain tissue had occurred after the boy’s death as his body was maintained on a respirator for two days until organs could be procured. The boy instead died of a virus, the expert determined.

Former Times staff writer Gus Garcia-Roberts contributed substantial reporting to this story before his departure from The Times in 2018. Times researcher Scott Wilson also contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.