Albert Frey’s first desert home design lives again

You’re no doubt familiar with architect Albert Frey’s work — a massive angular roof he designed with Robson C. Chambers greets drivers heading into Palm Springs on Highway 111. The soaring topper — it resembles a flying arrowhead — crowns the 1965 Tramway Gas Station, now the Palm Springs Visitors Center.

Thirty years prior, such extravagantly shady roofs were not on Frey’s radar. Rather, the desert modernist pioneer, fresh from assisting architect Le Corbusier in Paris, was interested in essential shapes: A few spartan boxes dropped on the desert floor would do for his first Palm Springs residential design, the Guthrie House.

Frey’s 1935 creation consists of three rectangular boxes sans overhangs, seemingly baking in the desert, yet cooled by cement floors and corrugated metal that helps deflect heat.

A series of renovation-giddy owners, however, disfigured the home with thick pink stucco, arched doors and windows and enough Hollywood Regency decor to out-glam Joan Crawford (Errol Flynn reportedly once rented the home, which was also a hangout for such luminaries as Marilyn Monroe and Frank Sinatra).

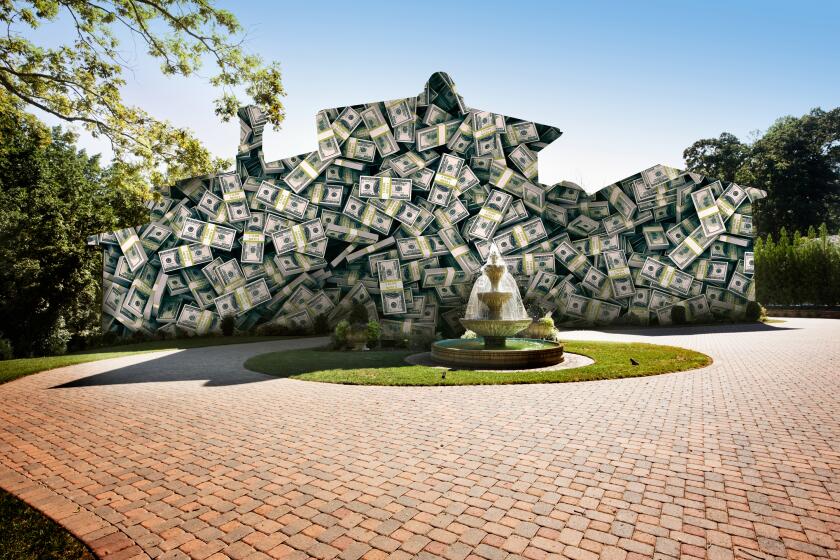

After a nearly $1-million renovation, the three-bedroom property has been returned to its intrinsic Frey roots; it’s now listed by BBS Brokers Realty for $2.399 million.

“I figured, nobody’s going to want this house — it was pretty frightening, a little spooky,” said Marina Rossi, founder of the Avi Ross Group, an L.A.-based design and real estate development firm. Rossi bought the home in 2015 for $745,000 with a Moroccan-style rehab in mind, but after some digging, received confirmation during escrow that it was Frey-built.

Rossi nixed her North African design spin and with her business partner daughter, Avalon Rossi, hired two architects before finally proclaiming, “We can’t do this,” rejecting traditional midcentury design plans with liberal overhangs.

Instead, the mother-daughter team decided to steward the rehab themselves, returning the home to Frey fundamentals. While the modernized result is not a true historic restoration, it hews closely to the architect’s spirit.

In short, the home’s a Frey, but now with added flair.

The Rossis read scores of books and accounts about the Swiss-born architect, who designed 200 area buildings and had enjoyed belated recognition — the enduring Midcentury Modern renaissance had begun gaining traction before his death in 1998.

The pair devised a “Frey test” with a central question that informed each design decision: What would Albert do?

The home was first stripped of its various froufrou, with jackhammers employed to blast off 3-inch-thick stucco the color of “Pepto-Bismol — it gave me a stomachache,” Marina Rossi said. She found a stray slice of original stucco between walls, and color-matched its off-white hue for new exterior paint.

The home was taken down to the studs to reveal a partial original footprint. Some additions were kept and others removed; extensions previously added to the bedrooms were so long they looked like bowling alleys, Rossi said.

Three styles of fireplace mantels were peeled away in favor of an unfussy cement surround, painted white, that frames the hearth.

Spanish tiles were pried from concrete floors, which were then reconditioned and coated with a gloss epoxy sealer to lend a sleek watery look. The duo installed custom maple cabinetry (based on later Frey homes) and reconditioned Frey’s existing cabinets. Also, they rejected sliding glass doors — a staple of classic midcentury design — in favor of emulating Frey’s original aluminum-framed glass doors.

A brick wall separating the kitchen and dining rooms (probably added in the 1940s or ’50s) was kept for its coveted texture. In an homage to Le Corbusier, each brick was painted white, allowing lines of cement to show through; it mimics a wall in the architect’s Paris atelier.

Raw corrugated metal, rusted to a vivid orange, was used on gates, on a sliding barn-style door and on doors to a den (the former garage). Frey was known for his inventive use of the material.

A pool house was added and the pool was resurfaced with black plaster to lend it a natural lagoon look. Hardscape consists of pavers, gravel and artfully placed stones and boulders that mimic the desertscape.

The result: a chic zen-like retreat wreathed by staggering mountain views.

The Guthrie House (built for James V. Guthrie) represents a transitional arc between Frey’s “East Coast sensibility to his definitive Palm Springs aesthetic,” said Joseph Rosa, author of “Albert Frey, Architect” (Rizzoli, 1990). Rosa helped the Rossis steer the renovation.

Before moving to Palm Springs, Frey worked with A. Lawrence Kocher in New York, designing the nation’s first all-metal residence, the 1931 Aluminaire House. In 2017, the disassembled demonstration model was shipped to Palm Springs where it awaits reassembly.

Among Frey’s other projects: Palm Springs City Hall (1952), the 1963 Aerial Tramway Valley Station and his 1964 residence, “Frey II,” a slender glass box cut into Mt. San Jacinto that’s shot through with a boulder.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.