Downtown’s historic office buildings, once abandoned, are again drawing tenants

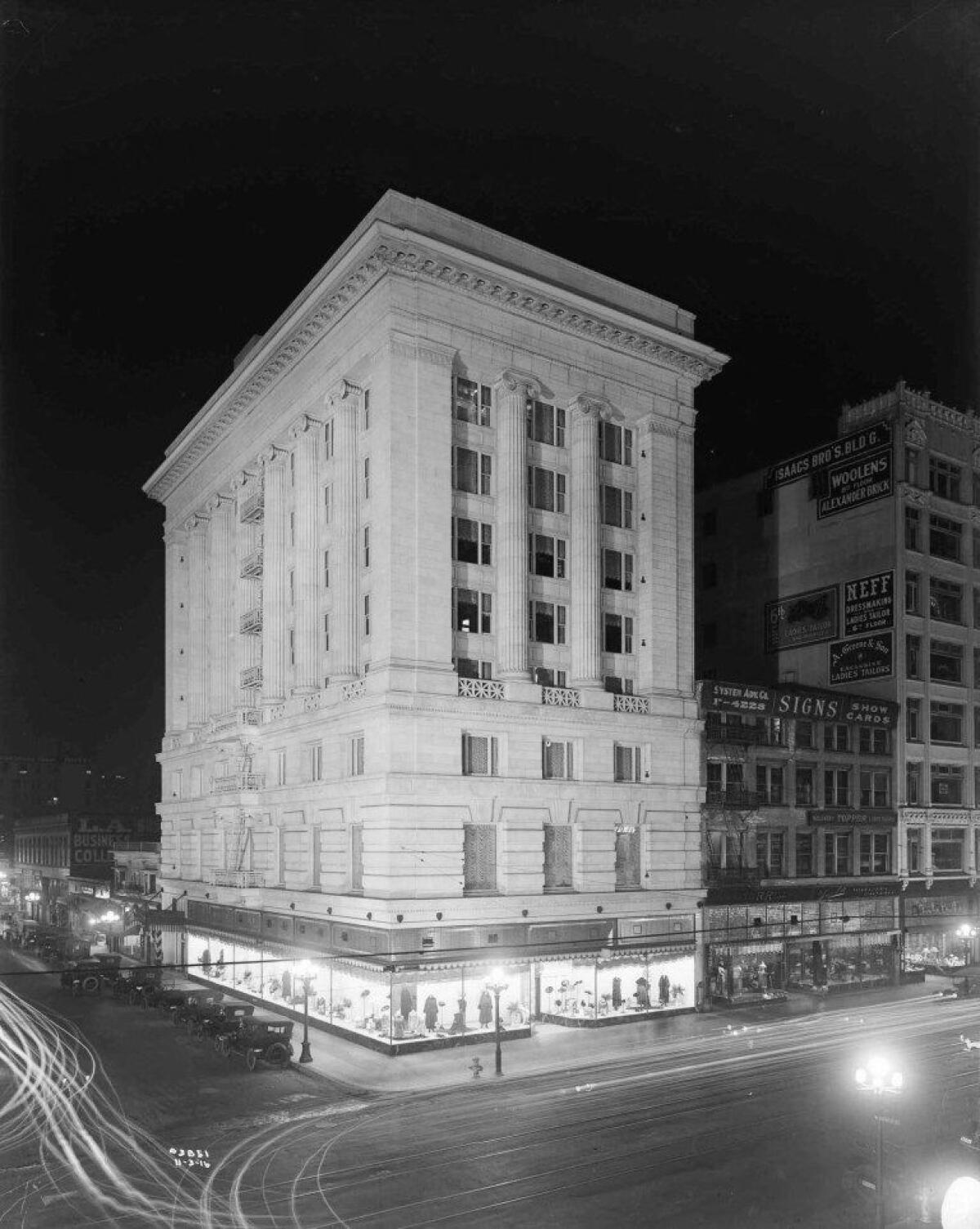

Just over a century ago, Hulett C. Merritt built an imposing white edifice on Broadway in downtown Los Angeles meant to reflect his stature as one of California’s richest, most successful businessmen.

It was a nine-story office tower designed to evoke the ancient Roman temple of Minerva, clad in exquisite white marble from the same Colorado quarry that supplied stone for the Lincoln Memorial being erected at the time in Washington.

Today, the long-vacant Merritt Building is covered in dark soot and graffiti, a lingering eyesore in a neighborhood on the mend. Its new owners, however, have begun a full-scale makeover to restore it to life as an upscale office building — an unusual but increasingly common decision among landlords in downtown’s Historic Core.

In a trend that would have been unimaginable only a few years ago, historic office buildings are being returned to the office market instead of converted to apartments, condominiums or hotels, which has been common for the last decade and a half.

The pattern reflects tenants’ changing tastes in office space and the comeback of downtown. It also reveals a silver lining to what has been widely regarded as one of the worst planning decisions in the city’s history — the wholesale removal of the aging Bunker Hill residential neighborhood in the 1950s and 1960s to make way for what was then called “urban renewal.”

Victorian homes that had once been among the city’s finest addresses were wiped away. By the 1980s and ’90s, gleaming office skyscrapers including the 73-story U.S. Bank Tower populated Bunker Hill and white-collar businesses’ abandonment of L.A.’s original downtown on Spring Street, Main Street and Broadway was complete.

Many of the old offices were left mostly vacant or converted to manufacturing uses, but the buildings remained standing as a new downtown core emerged.

“Development went elsewhere and there wasn’t interest in tearing them down to build new tall buildings,” said Linda Dishman, president of the Los Angeles Conservancy. “The heedless destruction of the Bunker Hill neighborhood may have saved Spring Street.”

Now many business owners and their employees find old buildings charming and better reflections of their company identities than the more impersonal mirrored-glass high-rises built to impress the elites of 20th century corporate America.

“Everybody who comes here identifies us with this space,” said architect Douglas Hanson, whose firm HansonLA moved from the U.S. Bank Tower to the Corporation Building on Spring Street. “It gives people a real window into what we do and it’s consistent with our brand.”

The slim, 14-story Corporation Building dates to 1915, when small floor plates and big windows were typical. “These buildings were built to use natural light,” Hanson said, which appeals to architects — up to a point.

When he moved his 20-person firm to a full floor in the old building about six years ago, it had no overhead lighting and no heating or air conditioning. The office had last been used for garment manufacturing.

“It was raw space,” Hanson said, “like working in the garage.”

Outside, people on the sidewalk included enough shady-looking characters to give visitors pause. “We had some clients, especially international clients, who were afraid to come,” Hanson said.

Homelessness is a persistent issue, but now there is more pedestrian activity on Spring Street than there is on Bunker Hill, including residents walking their dogs and sipping coffee in sidewalk cafes.

“We like the diversity of people,” Hanson said, “and working in a neighborhood where people are actually living.”

Hanson’s landlord, Izek Shomof, said he had success making residential lofts in historic buildings but noticed the rising popularity of “creative offices” — typically older buildings that sported exposed ceilings, polished concrete floors and other minimal finishes.

So Shomof, an Israeli-born real estate investor and developer who has been active in the Historic Core for years, added lights, air conditioning and other improvements to his Corporation Building. Recently, he added a food hall on the ground floor with multiple small restaurants.

“I saw there was a huge demand and said why not try it,” Shomof said. Today, his office tower is mostly leased. “It’s working out fine for us.”

The economics of historic buildings have tilted in favor of offices over apartments in many cases, said Phillip Sample, a real estate broker at CBRE Group Inc. Monthly rents are about the same for both categories but it costs less to prepare offices because they require less plumbing for bathrooms, kitchens and washing machines.

Rents for older buildings-turned offices in the Historic Core and Arts District can be as high as $3.75 per square foot a month, CBRE said, roughly the same as top towers on Bunker Hill. That’s in spite of the fact that many older buildings lack built-in parking.

“The kids nowadays are walking to work,” Sample said, or arriving via bicycle, ride-sharing services such as Uber or public transportation. “It’s just so much more easy than it used to be” to commute without a car, he noted.

Downtown was served by a steady stream of streetcars when industrialist Merritt completed his namesake building in 1915 at Broadway and 8th Street.

His personal offices were on the top floor and the columned temple-like exterior was clad in bright Colorado Yule marble. The Times was unstinting in its praise, calling Merritt’s tower “not only the most luxurious office block in the United States but the tallest building of all white marble in the world.”

The Merritt Building has been mostly vacant for decades, but Canadian developer Bonnis Properties paid top dollar — $24 million, or $429 per square foot — last November and plans to have it back on the office rental market in 2019.

Principal Kerry Bonnis declined to say how much the renovation will cost, but promised to make the property stand out again.

“We can’t wait to clean it up and surpass the days of its former glory,” he said. “We are quite confident we will find a tenant or a number of tenants.”

Bonnis considered converting the building to residences, but decided that its location and layout would support office use.

Home Savings & Loan Assn. remodeled the lower three floors of the building inside and out in the 1950s when it had a branch there, but Bonnis and his historical consultants are working from old photos to try to erase the mid-century makeover.

“Our intention is to strip all that and take the lower levels back as close as possible to the original architecture,” Bonnis said. “The original storefront is fabulous.”

Its exterior imitation of the temple of Minerva also makes the building stand out, said Dishman of the L.A. Conservancy.

“It was very common in the first two decades of the 20th century to reproduce these classical buildings,” she said. “We don’t have a lot of these in Los Angeles and this is a very spectacular example of the style.”

As downtown’s old offices are rejuvenated one by one, some will still be converted to residences or hotels, such as the trendy Ace Hotel in the former United Artists office building on Broadway or the NoMad Hotel under construction in the former Giannini Place on 7th Street.

Bonnis Properties is turning the former offices in its 1920s-era Foreman & Clark Building at 7th and Hill streets from jewelry-making workshops into 125 apartments, Bonnis said.

The linear layout that supported numerous small offices off a central corridor isn’t conducive to making the wide-open spaces that are in vogue for office collaboration now.

“Narrow hallways and maximum length don’t work so well,” Bonnis said. “It’s smart of the city to let developers and the market dictate which new uses are most appropriate. It will accelerate the entire renovation of downtown.”

Other old office buildings being restored to office use include the former L.A. Jewelry Mart built in 1917 at 7th and Olive streets and the long-vacant headquarters of the defunct Herald Examiner newspaper built on Broadway at 11th Street in 1914, according to CBRE.

The hulking 12-story Western Pacific Building erected north of the Herald Examiner on Broadway in 1925 also is being restored to the office market after years of being used for garment manufacturing. It will be available for rent next year, real estate broker Andrew Tashjian of Cushman & Wakefield said.

Bonnis, who is based in Vancouver, Canada, said he believes L.A.’s downtown office rental market can support these and several other “new” office complexes arriving within a few years of each other.

“There is no question that when multiple buildings come to market there is a synergy and excitement that becomes contagious,” he said. “This repositioning has been a long time in the making.”

Twitter: @rogervincent

ALSO

Nordstrom's newest store aims for a personal touch — and no clothing racks

As bids for Amazon's headquarters come due, tech has a chance to spread the wealth

Harvey Weinstein loses key supporters, including advisor Lisa Bloom, who came under pressure to quit

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.