As bids for Amazon’s headquarters come due, tech has a chance to spread the wealth

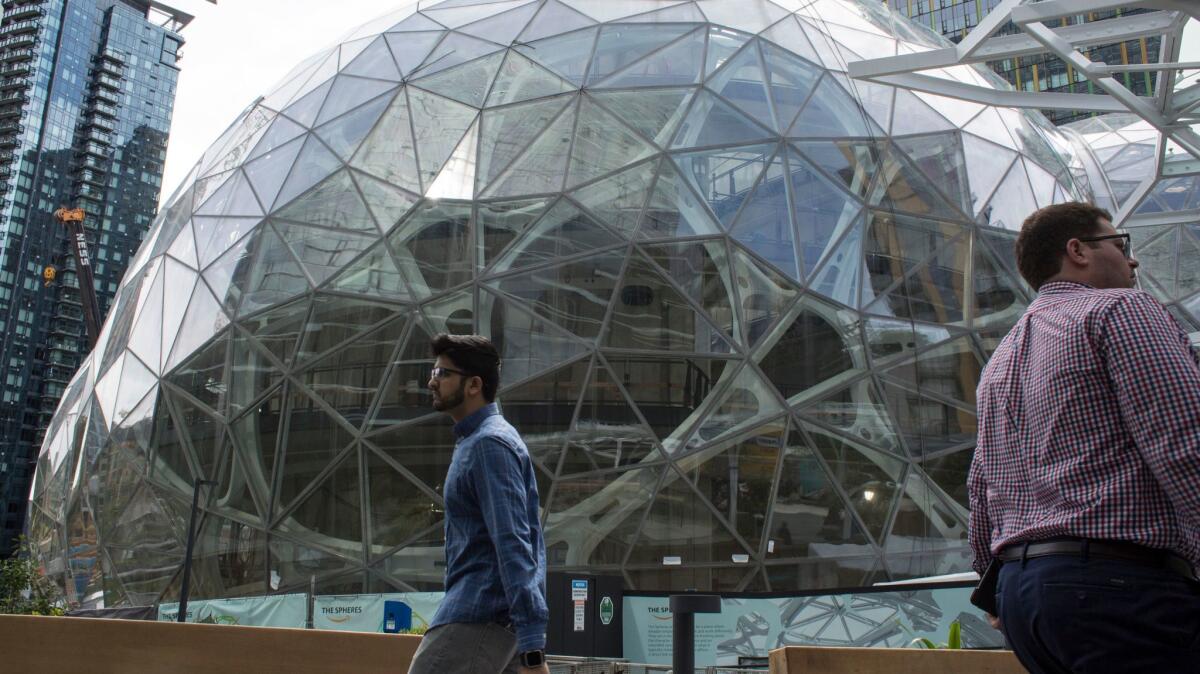

As Amazon established its dominance in online retail, logistics and cloud computing, the company’s headquarters in Seattle grew appropriately massive. Today it represents a $5 billion investment in 33 buildings, 8 million square feet and more than 40,000 employees.

Just this month, the digital giant confirmed it would be leasing another 722,000 square feet in a 58-story tower in the heart of the city’s downtown.

Amazon has helped establish Seattle as one of the great tech meccas, behind the San Francisco Bay Area. But the concentration of tech growth on the West Coast has come with a cost, in terms of skyrocketing housing costs and jammed freeways.

Now, as Amazon ponders where to locate a second headquarters site and 50,000 workers — proposals are due by Oct. 19 — it is raising questions about whether the industry, and America, would be better off spreading the tech-jobs wealth.

Clustering is not new to tech. Think Los Angeles and Hollywood. Or Detroit and automakers, Pittsburgh and steel, Houston and oil. Like those earlier examples, tech centers were kick-started by one or two big successful companies. In Silicon Valley, it was Fairchild Semiconductor and Hewlett-Packard; in Seattle, Microsoft.

The advantages of clustering are well-known: Companies get easy access to specialized investment expertise and skilled workers. Workers have many choices of employers. Engineers with an idea can break away to form a start-up knowing the infrastructure is already in place.

“The history of the United States is wrapped around this clustering,” said Christopher Thornberg, founding partner with Beacon Economics. “If you are ahead of the game when an important cluster is formed, it gives you an advantage for decades to come.”

That dynamic can be seen in the desires Amazon set out for its new headquarters site. The company says it wants a metro area with more than a million people, a highly educated labor pool and a strong university system.

Another request? An international airport with daily direct flights to Seattle, New York, the San Francisco Bay Area and Washington, D.C.

Amazon says it will make its choice known next year.

“It’s basically narrowing down the [competition] to a handful of cities,” UC Berkeley economist Enrico Moretti said. “And even those that qualify under that criteria, there are some that have much more of a comparative advantage.”

The costs of such concentration, however, are growing.

Years of high job growth in the well-paying sector — a software developer earns roughly $100,000 annually, double the national average for workers in all industries — have helped drive up rents by 46% in Seattle since 2012, and 35% in San Francisco. Home prices have risen even faster, to a median of $690,200 in Seattle and $1.2 million in San Francisco, according to Zillow, a Seattle-based real estate tech company located a short distance from Amazon’s headquarters.

In the San Francisco-Oakland-Hayward metro area, 17% of commuters traveled an hour or more to work in 2015, up nearly four percentage points from 2012, according to a Brookings Institution analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data.

Many of the tech giants already maintain decent-sized operations away from the coasts. Cloud computing firm Salesforce, which will move into the tallest building in San Francisco by early next year, also has expanded in Indianapolis since it acquired a local company there in 2013.

The company says it now has 1,600 workers in Indianapolis and will hire an additional 800 by 2021. It’s even launched a campaign to persuade its workers — even top talent — to move there from the Bay Area.

“Places like San Francisco, Santa Clara and Palo Alto, they are tapped out,” said Bob Stutz, the company’s chief analytics officer. “Even for us — with the new tower in San Francisco — we really have space problems, because we are growing so fast.”

Mark Muro, director of policy at the Metropolitan Policy Program at the Brookings Institution, said more companies should view cities in the Midwest and the South as attractive because employees can find an affordable home there and the local community will probably be welcoming. There are also top-notch universities and enough good talent, he said.

For Salesforce, Stutz said, cheap housing in Indianapolis has been a major recruiting tool. Other tech firms have also set up operations in the city recently.

“Having a great quality of life for people is better than putting everything into Silicon Valley,” he said. “We really believe Indianapolis will eventually become another hub.”

But industrywide, tech companies are increasingly keeping their top engineering talent close and locating lower-paid jobs, such as tech support, in secondary cities, research from employment website Indeed.com shows. The disparity only feeds the concerns of some observers that parts of the U.S. are being left behind by a digital economy that benefits from the same forces — automation and globalization — that have hammered workers in the manufacturing sector.

“Past practices and prejudices about what the flyover zone is have precluded some of that distribution,” Muro said. “Frankly, I am not sure big tech has much familiarity with the middle of the country and vice versa.”

Whether that is contributing to a national economic divide is open to debate.

Regional inequality has been getting worse for a long time, with the gap between rich and poor metros rising since the late 1970s, maintains Jed Kolko, chief economist with Indeed.com.

A recent report from the Economic Innovation Group said the nation’s most distressed cities — judged by poverty, job growth and other factors — tend to be former industrial hubs in the Midwest and Northeast. The most prosperous cities tend to be tech hubs or fast-growing places in the Sun Belt with diverse economies.

There is an urban-rural divide as well, according to the group, with smaller counties 11 times more likely to be distressed than larger counties.

The situation can worsen as highly educated individuals move away from their hometowns in search of good jobs.

“There is a downward spiral effect,” said Steve Glickman, executive director of the Economic Innovation Group and a senior economic advisor in the Obama administration.

The sagging fortunes of blue-collar workers have been credited with worsening the country’s cultural and political divide and leading, along with white resentment, to the election of Donald Trump.

“It creates a huge divide in our political system, and I think you saw that in 2016,” Glickman said.

Steve Case, the co-founder of AOL, recognized that divide when he launched his “Rise of the Rest” bus tour in 2014. Case and his company, Revolution, invest in start-ups outside the traditional coastal tech hubs.

During the bus tours, Case holds competitions, where entrepreneurs pitch their new technologies in hopes of securing a $100,000 personal investment from him.

His next trip, starting Tuesday, will include stops in Harrisburg, Pa.; Ann Arbor, Mich.; Indianapolis and Columbus, Ohio. Case will be joined by J.D. Vance, author of “Hillbilly Elegy,” which chronicled the slipping fortunes of Appalachia.

“It’s important to remember that America itself was once a start-up and became the greatest economy in the world, thanks to the efforts of entrepreneurs who built not just companies, but entire industries in the heart of the country,” Case said upon launching his first tour.

Not everyone is convinced about the seriousness of the urban-rural divide, though. And some experts note there are other ways to catch up than winning an expensive beauty contest for a corporate headquarters.

Thornberg, the economist, said his analysis shows no clear link between faster income growth and large counties. In fact, he said the places that had the fastest growth between 1995 and 2015 were smaller rural areas in states that have experienced a shale oil boom, including Williams County, N.D., located in the Bakken oil field.

“There are other ways of making income outside of being an urban, creative economy,” Thornberg said.

States could spur growth by barring non-compete clauses and loosen their professional licensing requirements to attract more highly skilled workers, said John Lettieri, senior director for policy and strategy at the Economic Innovation Group and a former foreign policy aide to Republican Sen. Chuck Hagel. Cities can spruce up their downtowns and lure immigrants, whom studies show start businesses at a higher rate than Americans born here, he said.

Instead of focusing on attracting one mega-company such as Amazon, Lettieri said, struggling areas should work to spur business creation locally, in part by investing in colleges such as Southern Illinois University Edwardsville.

That’s where Matthew Kulig received his undergraduate degree, before settling down 20 minutes away in St. Louis. In 2008, he co-founded Aisle411, which develops smartphone software that allows shoppers to quickly find items at big retailers.

Kulig said getting funding can be tougher in less established tech centers, but there are positives to being in St. Louis.

He’s been able to hire skilled workers from local universities, and the city is convenient to his retail customers headquartered in the Midwest and South. He’s also been able to pay them less than he would in Silicon Valley, allowing him to raise less money to get the business off the ground.

“It’s taken 70 years to build Silicon Valley into what it is today and a lot of towns, St. Louis, Chicago, Cleveland … they are trying to figure out where they fit in the ecosystem,” he said.

For his part, Kulig said he now employs 20 and is working with Google on augmented reality.

Follow me @khouriandrew on Twitter

UPDATES:

2:40 p.m.: This article was updated with data on commute times in the San Francisco area.

This article was originally published at 10:55 a.m.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.