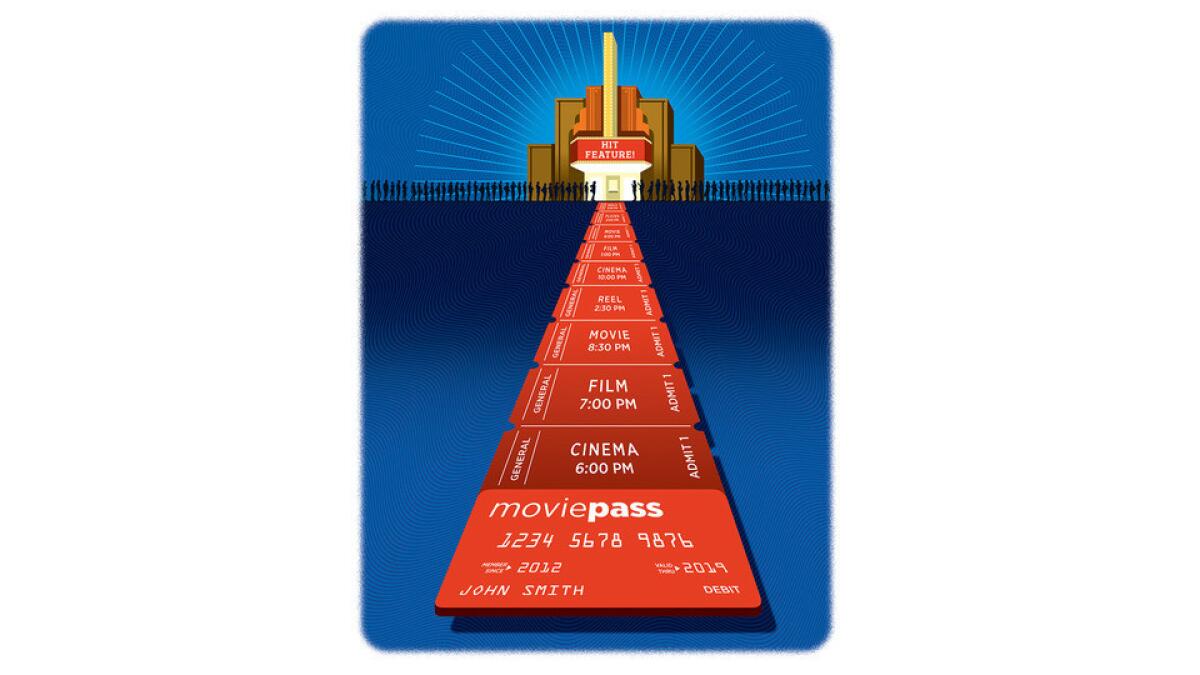

MoviePass, the $9.95-a-month cinema subscription service, could shake up the film industry — if it survives long enough

West Hollywood resident Andrew Woloz, 28, used to go to the movies about once a month. Lately, though, he has visited his local AMC Dine-In Sunset 5 or Pacific Theatres at the Grove almost weekly.

The reason behind his burst of attendance is MoviePass, a popular subscription service that lets its users see one movie a day for $9.95 a month — a deal so good that Woloz used it to watch the quiet indie drama “Lady Bird” twice.

For the record:

2:10 p.m. April 14, 2018An earlier version of this story incorrectly described the location of Pacific Theatres.

“It saves me money and it gets me to go to the movies more,” said Woloz, who works at the Beverly Hills record label Concord Music. “I said to myself, ‘This is amazing. It seems too good to be true, but I’m going to roll with it.’”

The bargain has proved enticing for moviegoers, who have signed up in droves since MoviePass slashed its price from $30 a month last summer. The service, which allows subscribers to see as many as 31 movies a month with its app and red debit card, currently counts more than 2 million subscribers, up from 20,000 last year. Company executives anticipate surpassing 5 million subscribers by the end of this year.

MoviePass allows moviegoers to see virtually unlimited movies in theaters for just $9.95 per month.

And MoviePass is expanding its reach. This month, its parent firm bought the showtime listing service Moviefone for $8.6 million in cash and stock. MoviePass, based in New York, has even branched into the business of acquiring and distributing movies.

But the 7-year-old company’s rapid ascent from relative obscurity to prominence among cinephiles has also made it the most controversial player in the exhibition business. Sometimes billed as the Netflix of cinemas because of its low-cost, high-volume strategy, the service could dramatically change the way Americans go to the movies and increase admissions — if it survives long enough.

Supporters see the MoviePass model as a much-needed response to two long-term trends in the movie business: shrinking attendance and rising prices. The number of tickets sold in the U.S. and Canada fell 6% to 1.24 billion last year, the lowest level since 1995, according to data from the National Assn. of Theatre Owners.

Meanwhile, ticket prices have continued to rise as movie theaters upgrade auditoriums to better compete with cheap and convenient at-home options such as Netflix. The average movie ticket price rose to a record $8.97 in 2017, according to the theater owner association. In cities including Los Angeles and New York, the prices are significantly higher.

Some analysts welcome the model as an innovative way to fill empty seats.

“If MoviePass is helping to drive incremental theater visits at full-ticket price, I don’t see any reason it would be negative,” said Eric Wold, an analyst at B. Riley FBR Inc. who follows the cinema industry.

While many users see it as a godsend, some theater owners and studio executives worry that MoviePass will hurt the industry. Some executives who have dealt with MoviePass complain that the company has used strong-arm tactics, including blocking theaters from its app, to pressure exhibitors to share a cut of their sales.

AMC Theatres, the world’s largest cinema operator, sharply rebuked MoviePass last year, calling it a “fringe player.” AMC has repeatedly called the $9.95 price point “unsustainable” and also blasted MoviePass for making what it called “false statements,” exaggerating the service’s contributions to the theater chain’s profit.

One of the industry’s biggest concerns is that MoviePass’ inexpensive offering could devalue the cinematic experience by getting millions of people used to going to the movies while paying very little. And if MoviePass goes out of business, those customers may not come back.

“If any subscription service provider gets very far along and goes out of business, they will leave a lot of unhappy moviegoers,” said John Fithian, president and chief executive of the National Assn. of Theatre Owners. “So sustainability is a big, big deal.”

MoviePass declined to comment for this article.

Theater owners aren’t completely opposed to the idea of subscriptions, and some have tried their own versions. European chain Cineworld, which recently bought Regal Entertainment, has a subscription program charging about $25 a month for unlimited 2-D films. Plano, Texas-based Cinemark Theatres recently announced a new $8.99-a-month program called Movie Club, which offers a ticket credit each month at its theaters, plus discounts on snacks. The Cinemark deal drew 120,000 sign-ups in its first 12 weeks, CEO Mark Zoradi said.

“The whole goal here is to increase attendance,” Zoradi said. “We’re trying to make the moviegoing experience frictionless and affordable.”

MoviePass’ all-you-can-watch model is attractive to consumers because it can be used anywhere, except for high-end luxury cinemas including Arclight and IPic. It doesn’t work for 3-D movies.

Those who sign up for MoviePass receive a debit card in the mail. When they’re close enough to a theater, they use the MoviePass phone app to select the showtime for the film they want to see. MoviePass then loads the exact dollar amount of the ticket onto the card, which the customer swipes at the box office. In other words, MoviePass pays the full price for each ticket, leaving many to wonder how the model is sustainable.

Publicly traded parent company Helios & Matheson Analytics Inc. hasn’t disclosed earnings for MoviePass since it bought a majority stake in the then-privately held upstart for $27 million in August (Helios & Matheson is expected to release its full-year financial report Monday), but the service is probably burning cash at a brisk pace.

The cost of a single ticket in Los Angeles or New York is often much higher than the monthly fee. When there’s a rush of ticket buying for a massive box-office hit, such as Marvel’s “Black Panther,” MoviePass’ losses accelerate, analysts said.

“They’re going to get people who love to gorge and watch as many movies as possible,” Wedbush Securities analyst Michael Pachter said. “It just can’t work.”

Reflecting those concerns, New York-based Helios & Matheson’s stock has plunged 50% this year to about $3 a share.

MoviePass is led by CEO Mitch Lowe, who once clashed with studios as an executive at discount kiosk disc rental company Redbox. He and Helios & Matheson Chairman and CEO Ted Farnsworth are betting that most people will use the service like a gym membership, using it frequently at first before reverting to regular moviegoing habits.

“By the end of this year, we’ll be cash-flow positive, which is amazing for a subscription service so young,” Farnsworth told The Times this month.

The company will need to boost its revenue from sources other than subscriptions to become profitable. In March, Lowe said that the projected 5 million subscribers for MoviePass would account for 20% of U.S. ticket sales. For that to happen, each MoviePass subscriber would have to buy about four tickets a month, at a cost to the company of $36 a month for each subscriber, based on the current average ticket price.

To improve its finances, MoviePass also intends to negotiate revenue-sharing deals with cinemas. Once MoviePass gets to a certain size, it could persuade theater chains to give it a discount of $2 or $3 on the tickets it buys.

Some small exhibitors have shown signs of support. Flix Brewhouse, a dine-in chain based near Austin, Texas, with five locations and 41 screens, has a deal with MoviePass that gives the start-up a small discount on tickets. MoviePass in March signed a deal with Landmark Theatres, an art-house chain with 53 locations, to let people use MoviePass to reserve seats online.

“So far we think it’s been a net positive bringing in new business,” Landmark Theatres owner and tech investor Mark Cuban said in an email to The Times.

Some smaller exhibitors say the service encourages people to see less-popular movies that would otherwise struggle to compete with Hollywood blockbusters in theaters. Studio Movie Grill CEO Brian Schultz, who is an investor in MoviePass, said more than 70% of MoviePass subscribers coming to his theaters are millennials, a challenging demographic for the industry.

“What’s the risk of … experimenting?” Schultz said. “At the end of the day, don’t you want to be increasing attendance?”

Nonetheless, MoviePass’ negotiating tactics have angered many of the biggest players in the industry. In January, MoviePass dropped 10 of AMC’s most popular and priciest cinemas from its app in certain locations including Los Angeles and New York, escalating a longstanding feud with the Leawood, Kan., company. AMC had already rejected the idea of sharing revenue with the service.

“AMC has absolutely no intention — I repeat, no intention — of sharing any — I repeat, any — of our admissions revenue or our concessions revenue with MoviePass,” AMC chief Adam Aron said in November.

MoviePass ended its blackout of the theaters this month, saying it was a way to test consumers’ behavior.

The company is also hoping film distributors will pay it to promote new films on the app, including lower-profile releases that people might not otherwise see. The start-up is hoping the data it collects about its users will prove attractive to studios and distributors.

Indie distributor the Orchard, for example, recently partnered with MoviePass to promote the upcoming heist drama “American Animals,” which the two companies acquired after the Sundance Film Festival. To smaller distributors, a push notification to more than 2 million smartphone users could make a difference at the box office.

However, several studio executives, who spoke to The Times on condition of anonymity because their dealings with MoviePass are private, questioned the app’s effectiveness as a marketing tool for major films, noting that studios already get data from a variety of sources.

“They’ve come in with this unsustainable business model, and they’re using threatening tactics to get people to play ball,” said one studio executive who was not authorized to comment.

Then there’s the issue of online privacy, which has taken center stage amid Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s testimony on Capitol Hill this month about how the social media giant handles and tracks user data.

MoviePass CEO Lowe sparked an online blacklash in March when he spoke candidly about the amount of user data the company collects.

“We watch how you drive from home to the movies. We watch where you go afterwards,” he said at a conference panel titled “Data Is the New Oil: How Will MoviePass Monetize It?” “We know all about you.”

He later walked back the comments, saying MoviePass takes customer privacy “extremely seriously” and does not track location data when the app is not active.

Woloz, the MoviePass user in West Hollywood, said he’s not bothered by the data collection, which he sees as a reasonable trade-off.

“I don’t see a problem with it,” he said. “If that allows me to go to the movies for 10 bucks a month, hell yeah.”

To read this article in Spanish, click here

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.