Padma Lakshmi explains why she left her knives packed when writing ‘Love, Loss, and What We Ate’

Author-actress Padma Lakshmi in New York on March 23, 2016.

NEW YORK — If you ever happen to interview Padma Lakshmi, do yourself a favor and let her pick the location. That way, you might just find yourself enjoying a piping hot plate of spicy orecchiette at an unassuming East Village trattoria while the former model converses in fluent Italian with the restaurant’s owner.

To anyone who’s watched “Top Chef,” the popular Bravo competition series that has introduced a generation of American TV viewers to phrases like sous-vide and mise en place, it should come as no surprise that Lakshmi, 45, would turn a standard interview into a culinary adventure.

What may be more unexpected, particularly given Lakshmi’s glamorous but inscrutable TV persona, are the revelations in “Love, Loss, and What We Ate: A Memoir” (Ecco: 336 pp., $26.99). She writes with candor about her romances with author Salman Rushdie and billionaire Teddy Forstmann, her struggle with debilitating endometriosis, and the acrimonious legal battle for custody of her daughter, Krishna, now a spirited 6-year-old who tagged along with her mother to the interview. The memoir, which Lakshmi will discuss April 9 at the L.A. Times Festival of Books, also delves into childhood traumas, including sexual abuse, the car accident that resulted in a 7-inch scar on her right arm, and the rootlessness that arose as she shuttled back and forth between America and India.

“For so long, the only thing that people have known of me or seen me in is ‘Top Chef,’ That’s a very slim and narrow picture of me to have,” said Lakshmi, taking a generous forkful from her plate of rigatoni swimming in Amatriciana sauce — white sweater be damned. “As I enter the next phase of my career, I’m looking forward to making a living from something other than my likeness or image on TV. As a woman, I wanted to address certain issues that had been on my mind. As a feminist, I don’t think people talk openly about body image and self-esteem and being a brown girl in a white world.”

See more of Entertainment’s top stories on Facebook >>

The author of two previous cookbooks and an occasional contributor to outlets such as Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, Lakshmi had originally set out to write a guide to healthful eating. That idea was quickly dashed when she realized her dietary philosophy could be summed up “in three sentences.” Instead, Lakshmi decided to write something more personal that would appeal to readers even if they didn’t know her as the lady from “Top Chef.”

Quoting advice from an editor friend, she said, “What if you write the kind of book that you would love to read?”

With “Love, Loss, and What We Ate,” Lakshmi has attempted to emulate her favorite writers, M.F.K. Fisher, Mary Karr and Joan Didion — no small feat, as she acknowledged with a laugh. “The problem with me is that I feel I have really good taste in books.” Also influential was Judith Moore’s memoir, “Fat Girl,” which she calls “raw and real.”

“I wanted to write a proper book that would be respected, so people wouldn’t say, ‘She’s a cookbook writer,’” Lakshmi said, shrugging bashfully, “They would just say, ‘She’s a writer.’”

Woven throughout the book are stories of food, most of them far removed from the haute cuisine she regularly samples on “Top Chef.” There’s the kumquat and ginger chutney that comforted her in the dark days after her separation from Rushdie, the cream cheese and ketchup sandwiches she ate as a homesick child newly arrived in America, and kichidi, a simple lentil and rice stew she lived on while nursing her infant daughter.

The book’s title began as a joke between Lakshmi and her friend, the late Nora Ephron, who’d often ask how “Love, Loss, and What We Ate” was going — a reference to Ephron’s stage play “Love, Loss, and What I Wore.” It stuck.

Lakshmi seems to live by Ephron’s credo that “everything is copy.” The four-year process of writing the book came amid an intense period of extremes that began in 2006, when Lakshmi was hired to host “Top Chef.” The series became an Emmy-winning hit, but her booming career put a strain on her marriage to Rushdie. Another source of tension in their union was her long-undiagnosed endometriosis. The condition made sex painful for Lakshmi, dampening her libido, and Rushdie felt rejected. They divorced in 2007.

Lakshmi, co-founder of the Endometriosis Foundation of America, felt it was vital to include such intimate details given her advocacy work. “How could I hope to raise awareness about a disease if I myself wasn’t willing to speak openly about it and how it very directly and deeply affected my life?”

She has not read Rushdie’s 2012 memoir, “Joseph Anton,” which portrays her as a moody narcissist. In her account, he comes off as wildly insensitive and self-involved — at one point he calls her “a bad investment” — but also charismatic and brilliant.

“He has a right to his side, as do I,” Lakshmi said, gingerly wiping the corners of her mouth. “The truth is I’m the one who left him. I think he was very hurt, and that pain often metastasizes into anger.”

Lakshmi began to date another powerful, much older man, IMG founder Forstmann, but — somewhat remarkably, given her endometriosis — became pregnant with daughter Krishna by venture capitalist Adam Dell, whom she’d been seeing intermittently. A tabloid-friendly legal battle with Dell ensued, in the midst of which Forstmann was diagnosed with brain cancer. He died in 2011.

At the trattoria, Krishna came over and begged for a trip to the playground, and Lakshmi confessed that writing about the custody dispute was the most challenging. “I hope that my life is never that intense again,” she said.

But there is more to the memoir than Lakshmi’s turbulent personal life. She also writes lovingly of her mother and extended maternal family in India. Her parents divorced when she was a toddler, and with her father out of the picture, Lakshmi was raised by her mother in New York and later La Puente in the San Gabriel Valley. Money was tight, and Lakshmi spent most summers with her mother’s family in Chennai in southern India. In one particularly evocative chapter, she recalls napping on the cold marble floor next to her beloved grandfather, known as KCK, and running to the local “all-in-one” store to fetch him cups of ice cream.

One of her goals, she said, was painting “an accurate picture of what middle-class Indian life is like,” to go beyond the “mysticism and poverty.”

The move to the West Coast after her mother’s second divorce was difficult for Lakshmi, who was frequently mistaken for Mexican, and as a teenager temporarily changed her name to Angelique in an attempt to fit in. Over lunch, she credits her teachers at William Workman High School, where she was an honors English student, with instilling in her a love of literature — high school staples like “A Separate Peace,” “Catch 22” and “Metamorphosis.”

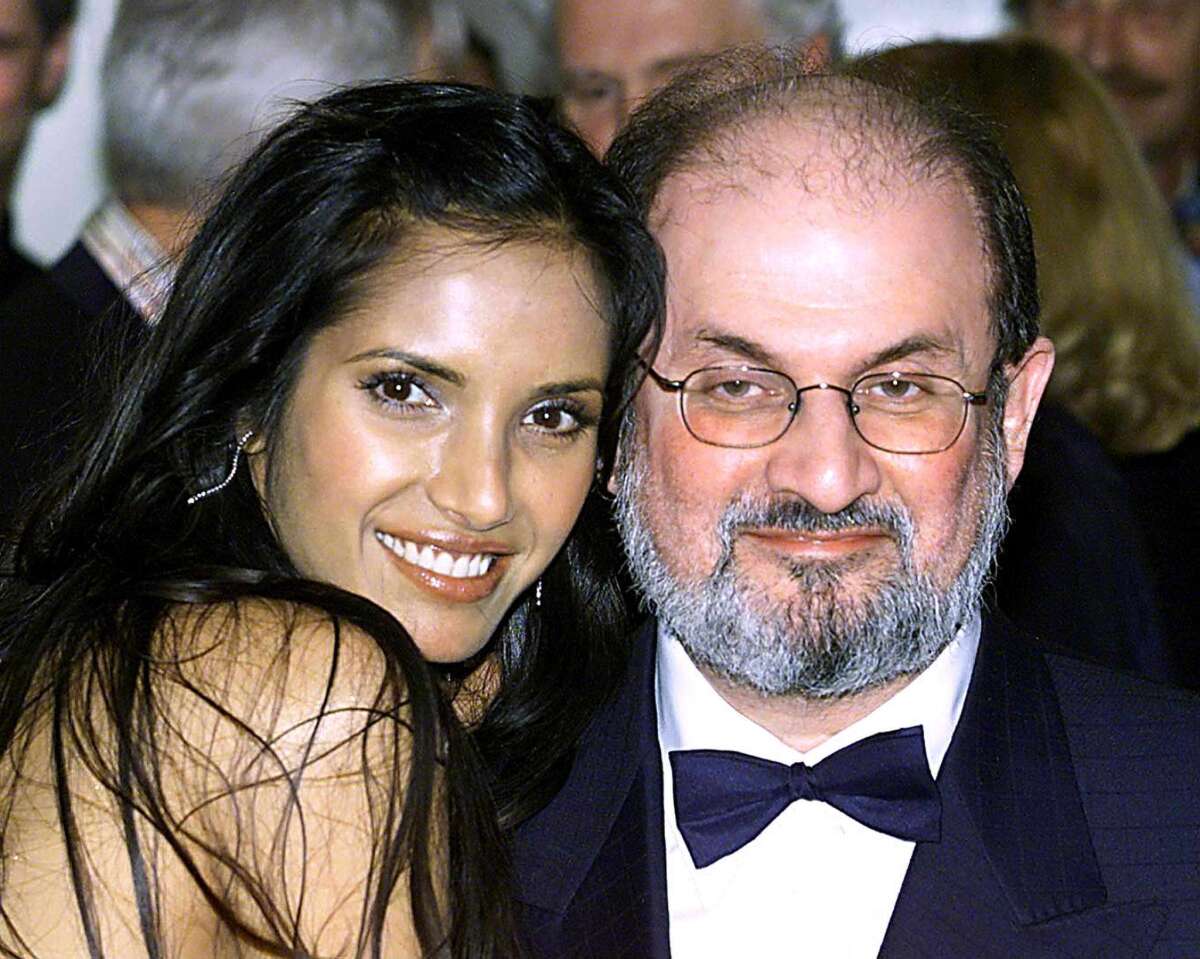

Salman Rushdie and Padma Lakshmi at a book event in Amsterdam on March 13, 2001.

A theme emerges in the pages of “Love, Loss, and What We Ate” of a beautiful woman determined to prove her other merits. She writes of the “imposter syndrome” she experienced alongside chefs like Eric Ripert on “Top Chef” and of the panic that often overcame her on posing for photographers on the red carpet with Rushdie: “I was captured being what I most feared I would become: an ornament or medal.”

Perhaps because of this nagging self-doubt, Lakshmi hasn’t read any of the reviews for “Love, Loss, and What We Ate.” For now, she says she’s simply enjoying the “liberating” sensation of having (metaphorically) bared all.

“There’s nothing anyone can say about me that I haven’t said myself.”

Lakshmi will appear at the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books on April 9.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.