‘Factory Girl’ loses its way as bio and pic

A brisk, superficial treatment of the tragic supernova life of Edie Sedgwick, “Factory Girl” disappoints as both biography and drama. The film charts the “poor little rich girl’s” trajectory as decidedly downward from Cambridge art student to Andy Warhol’s disposable model/actress/muse and finally to institutionalized drug addict. As a hopped-up ramble through the Pop Art ‘60s, it’s more like “That Girl” on speed than anything else.

Directed by George Hickenlooper from a screenplay by the improbably named Captain Mauzner (story credited to Simon Monjack & Aaron Richard Golub and Mauzner), the movie never gets beyond a psychosexual portrayal of Sedgwick as victim. Fans well-schooled in the lore of Warhol in general and all things Edie in particular will come away with no deeper understanding of the principals while newcomers will wonder what the fuss was all about in the first place.

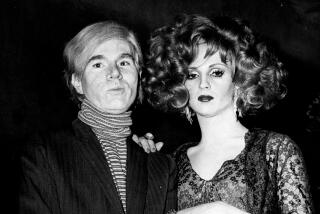

Sienna Miller stars as the doomed young woman, a debutante from an old New England family who was born in Santa Barbara and raised on a vast horse ranch. She ditches Radcliffe for the siren call of Manhattan with her heart set on a Holly Golightly existence. No sooner does she meets the enigmatic Warhol (played by Guy Pearce) than she’s down the veritable rabbit hole, seduced and consumed by the scene centered on the artist’s infamous Factory.

The film depicts the Factory as high school with more flamboyant clothes and hair and stronger drugs. Petty jealousies and backbiting create a toxic environment in which the hangers-on vie for Warhol’s attention and bask in his reflected brilliance. Sedgwick’s immediate ascendance to virtual prom queen portends her equally rapid fall from grace.

Edie and Andy become inseparable, morphing into one thin, platinum-haired being. They’re symbolized as outsiders who briefly share the white-hot spotlight, the swan offering her beauty to the ugly duckling who returns the favor by bestowing upon her capital-C cool. Unfortunately, the film never convincingly establishes why they are drawn to one another or meaningfully gets into the ways their mutual needs created a yin-yang synchronicity.

“Factory Girl” really goes astray with the arrival of Billy Quinn (Hayden Christensen), a Bob Dylan-esque rock star set up to be the anti-Andy. Like Pearce, Christensen throws himself into his role, but both are crushed by the sheer iconographic weight of their characters. Warhol and Dylan are too huge to be used as support beams in such a slight film.

The story is structured as a faux romantic struggle between “Dylan” and Warhol for Sedgwick’s aesthetic soul, with the options seemingly limited to an opportunist or a vampire. But the real battle for Edie was lost long before in a family that sent its children to a psychiatric facility the way another might have sent them to finishing school.

Warhol, with his Madison Avenue background, excelled at throwing the banal back in the faces of the Establishment and making them like it. Here, the filmmakers take that once subversive notion and reduce it to a public service announcement.

Hickenlooper uses a framing device with scenes of Miller as Sedgwick being interviewed by a therapist, a contrivance that serves little purpose other than to set out and then reiterate the film’s themes and provide exposition. The film heavy-handedly drives home its simplistic interpretation of Edie as the abused and abandoned target of a series of childish, manipulative men, with the ultimate blame saved for her family.

“Factory Girl.” MPAA rating: R for pervasive drug use, strong sexual content, nudity and language. Running time: 1 hour, 27 minutes. Exclusively at Landmark’s Westside Pavilion, 10800 Pico Blvd., Los Angeles, (310) 281-8223.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.