50 years after Candy Darling’s death, Warhol superstar’s struggle as a trans actress still resonates

On the Shelf

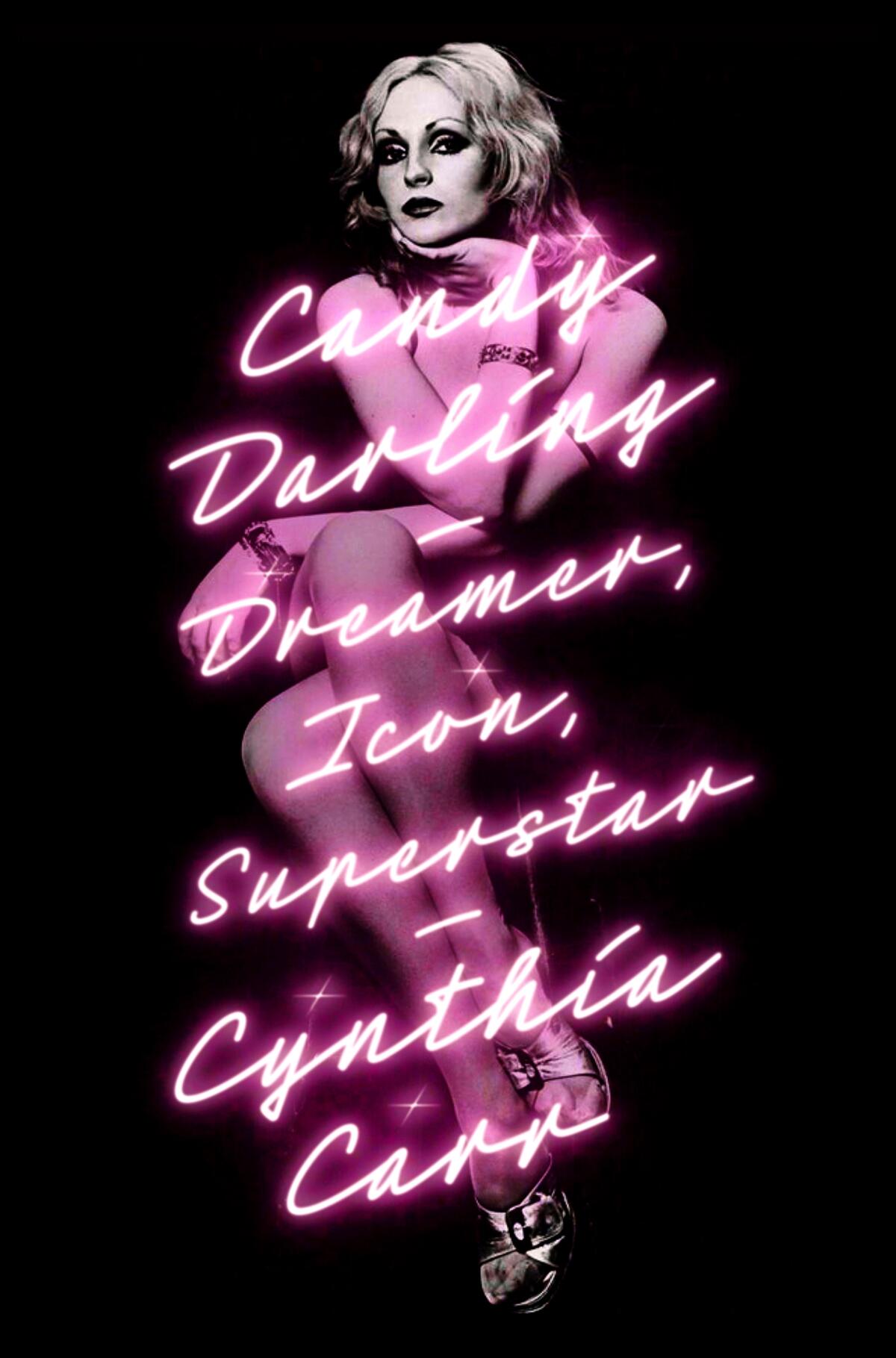

Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar

By Cynthia Carr

FSG: 432 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Warhol superstar Candy Darling is synonymous with doomed glamour — a gorgeous woman playing a dying gorgeous woman. The image of her laid up in the hospital, looking ready for her close-up in full makeup with one black rose on the pillow beside her, looks like a staged photo for a fashion magazine. But that picture, taken by Peter Hujar, is as staged as it is real. Candy Darling died of lymphoma in that hospital room in 1974. She was 29.

Candy, who was trans, lived a life ripe for biography. Her friend Jeremiah Newton set out to write her story right after her death. “He never told me why he stopped working on it,” Cynthia Carr, the author of “Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar,” tells The Times via email. “He did me an enormous service by interviewing some 50 people back in the 1970s and giving me the tapes.” Newton died in 2023.

‘Decoding Americana’s Queer Sensibilities,’ a group exhibit showcasing LGBTQ+ artists, encourages audiences to broaden their perception of queerness in America.

Even with those materials at her disposal, “Candy Darling” has taken Carr, also the biographer of artist David Wojnarowicz, 10 years to write.

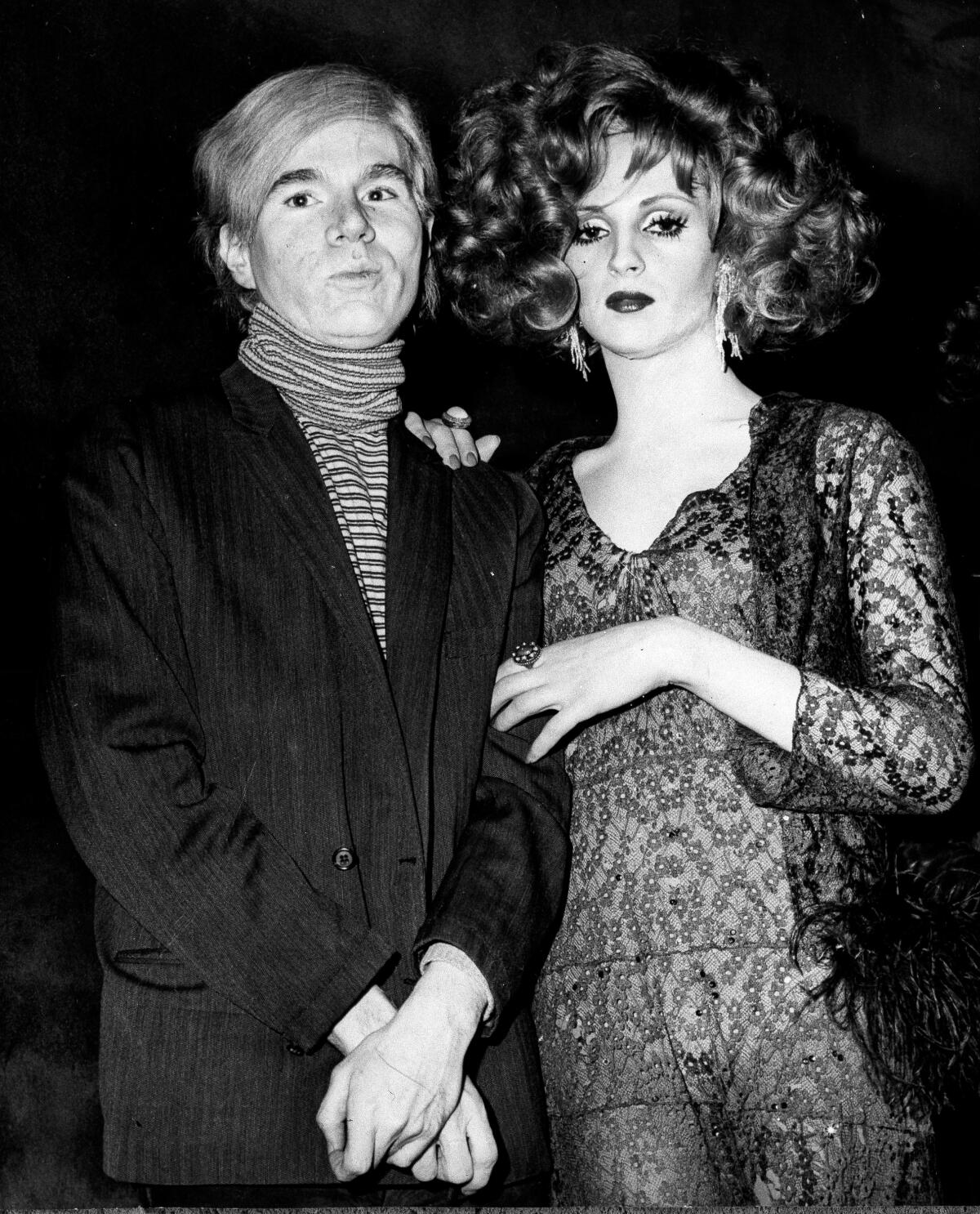

Candy’s struggle as a trans woman is the reason Carr undertook this project. One minute Candy’s in New York, on the arm of Andy Warhol; then, as Carr relates, she’s on her way home to visit her mother in Massapequa Park, Long Island, and her mother would say, “Don’t come till after dark. Don’t let anyone see you. Don’t answer the door.”

“I thought, ‘Wow, that has to be just a hint of what she went through as a trans woman back in the ’60s and early ’70s,’” Carr says. “I wanted to tell that story.”

For someone who lived such a tragically short life, Candy’s schedule was packed, and the worlds in which she traveled were diverse.

“I confess that I have never worked from an outline on any of my projects,” Carr admits. “But I start making a chronology immediately and keep filling it in as I do my research. I had the 48 tapes (and two transcripts) Jeremiah had done and the 98 people I interviewed myself — some of them multiple times. I went through old Village Voices, page by page, starting in 1967, when Candy appeared in her first play, until her death early in 1974. At that time, the Voice was the most essential and sometimes the only publication covering early Off Off Broadway, early gay liberation and the beginnings of second-wave feminism.” Carr’s research on Candy’s theater career is thrilling. It reveals a talented actress with whom directors were keen to work — more than “up-and-coming,” they describe Candy as brilliant.

Would Candy have had a future in Hollywood, had she lived longer? “Candy definitely wanted to make it in Hollywood but had more than a glass ceiling to deal with,” Carr says. “She would have had to live for quite a while — till now, say — to be accepted.”

In fact, a Candy biopic has long been in the works, and it’s now finally in the filming stage, starring trans actress Hari Nef. Nef’s casting is an answer of sorts to the controversy of cis actors playing trans characters. “I assume they’re basing the film on the documentary ‘Beautiful Darling,’ which really focuses on [Candy’s relationship with Newton],” Carr says. “As for the casting, a trans woman should play Candy.”

On view through May 27, ‘Witness,’ at WACO Theater Center, was curated by Tina Knowles Lawson and Genel Ambrose. The 14 featured artists explore themes of family, community and identity in their respective works.

Despite Candy’s celebrity in those worlds, the gulf between her experience as Candy Darling and in her family also is reflected in her archive. Some of her personal papers, including diaries and letters, ended up in the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, Carr says, but most are lost. Newton held on to many of the boxes of Candy’s things as long as he could, but when he was hospitalized, Carr says, “I’m sure some of them went into a dumpster.

“Writing a biography is a search for puzzle pieces,” Carr says, and sadly, other than Newton, Candy didn’t have a family member or a designated person to protect and ensure her legacy.

Candy was also poor — and unhoused. There was her mother’s house in Long Island to return to, which was not ideal, given the stigma and bigotry of the time. Candy mostly relied on friends and acquaintances, crashing in different places from night to night, week to week. Warhol lent her money and even paid for some of her hormone treatments. But Candy didn’t really have a home. As Carr writes: “Her life was not boring, but poverty and illness are boring.”

It was the hormones that most likely resulted in Candy’s cancer diagnosis and, ultimately, her death.

“I wish I could have seen a death certificate. According to Jeremiah, the doctor said it was lymphoma. Jeremiah also said that she’d been taking hormones that were later found to be carcinogenic and were taken off the market. I spent probably too much time trying to corroborate that,” Carr says. “What hormones were people taking in the early ’70s? Which one (or more) were taken off the market? I read a book on trans medicine, talked to a couple of doctors and combed through the internet, but we’re talking about a drug that would have been recalled almost 50 years ago. I never managed to figure it out. But, yes, it was the consensus at the time that hormones had caused her cancer.”

Though hormone therapy and gender-affirming healthcare have improved, the conditions in which trans people live in this country, and the violence they face, both from individuals and their own government, are still dire.

“I started work on this book in 2013, and transgender people have become much more visible in mainstream culture since then,” Carr says. “They’ve also become big targets for far-right politicians, and I can’t overstate how alarming this is. There’s so much anti-trans legislation out there it’s hard to even keep track of it — literally hundreds of bills coming up around the country. Bans on gender-affirming care, on participation in school sports, on using a bathroom that aligns with your identity and so on. Much of that’s aimed at young people, but it won’t end there. There’s an overall goal to erase transgender rights.”

“Candy Darling” is dedicated to the trans community. “May this account of one life make a difference,” Carr writes in the book’s dedication. “May you be understood. May you be appreciated. May you be loved.”

The point of any story is to relate a message — one that could, in the end, help others feel less alone. Literature is also one of the few ways we have to understand another human being — to place ourselves in the mind and experience of someone different from us.

Candy wanted to live and to be loved, to become a woman, to have a family, to have a home. “The word ‘trans’ implies a journey,” Carr writes. Candy’s journey, and the journey of trans people, continues.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.