Einstein’s Days in the Sun, Among the Hollywood Stars

He was perhaps the greatest thinker of the 20th century, but like many L.A. newcomers, he relaxed in the California sun, hobnobbed with Hollywood celebrities and watched the Rose Parade. He even helped children with their homework.

Seldom has a scientist won such public acclaim as Albert Einstein when he wintered in Pasadena in 1931, 1932 and 1933. An amateur violinist, he played one on one with the conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Local artists painted his portrait, sculpted him in bronze, and turned him into a puppet figure. Master violin maker Frank J. Callier carved a bow and special case with Einstein’s name inlaid in the wood.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. Sept. 15, 2004 For The Record

Los Angeles Times Wednesday September 15, 2004 Home Edition Main News Part A Page 2 National Desk 2 inches; 66 words Type of Material: Correction

Albert Einstein -- The L.A. Then and Now column in Sunday’s California section said Albert Einstein was employed by Princeton University. Einstein was employed by the Institute for Advanced Study, which is in Princeton, N.J., but is not affiliated with Princeton University. Einstein had an office at Princeton University while the institute was completing construction of its facilities, but he was not a Princeton faculty member.

But the FBI was watching too. He was one of four German scientists to sign an antiwar petition during World War I, and he joined the Zionist movement, which called for Jews to regain their biblical homeland in Palestine.

Excerpts from his FBI file -- which eventually filled 1,500 pages -- will be on exhibit at the Skirball Cultural Center beginning Tuesday, along with his love letters, manuscripts, diary and high school report card. (He earned top marks in algebra, geometry and physics and lower ones in French and geography.)

The exhibit includes a science lesson simulating a black hole and an interactive computer screen that allows visitors to delve into Einstein’s life. A video traces his birth in Germany in 1879, his lifelong battle with dyslexia, his Nobel Prize and his stands against segregation, anti-Semitism, McCarthyism and nuclear armament -- a type of weapon that his own theories helped to make possible.

The exhibit, which runs through May 2005, coincides with the centennial of Einstein’s “miracle year,” when he published his theories -- one of which is expressed by E=mc2.

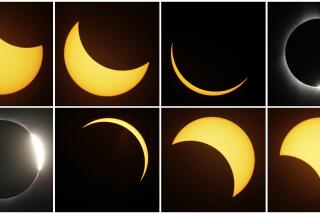

Einstein was a Swiss patent official when he first published the theories. Fourteen years later, in 1919, English astronomer Sir Arthur Eddington announced to the Royal Society that observations made during a solar eclipse supported Einstein’s 1905 theory of relativity. Overnight, Einstein became famous, and in 1921 he received the Nobel Prize in physics.

He was teaching at the University of Berlin in 1930 when Arthur H. Fleming, a lumber baron and president of Caltech’s board of trustees, came to woo him to the university.

Einstein agreed to visit for the winter on the condition that it remain secret, at least initially.

Fleming complied, tapping high-ranking government officials and friends to make travel arrangements. He even snagged financier J.P. Morgan’s yacht. But Einstein decided he didn’t want such a fuss and made his own arrangements -- unintentionally alerting the world.

After a 30-day voyage aboard the passenger ship Belgenland, he arrived in San Diego on New Year’s Eve 1930. He strolled into the dining room for breakfast that morning wearing only pajamas. When he disembarked -- fully dressed -- he was mobbed by reporters and photographers.

Thousands cheered Einstein and his second wife, his cousin Elsa, as the U.S. Navy band played Christmas carols. Although Einstein spoke English, he spoke German in San Diego as Elsa translated. Then Fleming drove them to Pasadena.

The next morning, a police escort with sirens blaring whisked the Einsteins to a bank building on Colorado Boulevard, where they watched the Rose Parade from a second-floor suite.

Einstein wanted to live on campus, but his wife wanted a house with a garden. So the Einsteins settled into a bungalow on South Oakland Avenue.

An amateur violinist, Einstein often played with small groups at his home, including Los Angeles Philharmonic conductor Artur Rodzinski. Neighborhood children knew his name and his most famous formula, E=mc2, though probably neither they nor their parents understood the equation linking energy and matter.

During their first three-month California stay, the Einsteins were guests of Charlie Chaplin at the premiere of his film “City Lights” at the Los Angeles Theater on Broadway. Afterward, they attended a dinner party at Chaplin’s Beverly Hills home, where Einstein was the luminary even among Hollywood celebrities.

“Here in Pasadena, it is like Paradise,” he wrote to friends in Germany in 1931. “Always sunshine and clear air, gardens with palms and pepper trees and friendly people.... Scientifically it is very interesting, and my colleagues are wonderful to me.”

The same winter, Einstein joined a busload of scientists on a visit to the Mt. Wilson Observatory, where he refined and confirmed his theory of relativity.

Like many visitors with intellectual curiosity, he visited the Huntington Library in San Marino. He also made his way to the Montecito home of scientist Ludwig Kast, where he was most comfortable being treated as a tourist, not a celebrity.

In Palm Springs, he relaxed at the winter estate of famous New York attorney and human rights advocate Samuel Untermeyer. He also visited the date ranch of razor blade magnate King Gillette, bringing back a crate of dates -- and a revelation.

“I discovered that date trees, the female, or negative, flourished under coddling and care, but in adverse conditions the male, or positive trees, succeeded best,” he said in a 1933 interview.

During Einstein’s three winters in Pasadena, students witnessed the shaggy-haired genius wheeling around Caltech on a bicycle, sailing paper airplanes from a balcony and at least once heatedly arguing with stern-faced Caltech president and Nobel physics laureate Robert A. Millikan on the steps of Throop Hall. (The subject of their argument remains a mystery. It could have been physics or even Einstein’s politics, which Millikan wanted kept low-key.)

Schoolchildren were known to knock on the door of Einstein’s home to ask for help with homework. He had difficulty turning down anyone. Hollywood High sophomore Johanna Mankiewicz, daughter of screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz, wrote to ask for an answer to a geometry problem. Einstein replied with a solution and a drawing.

But he most enjoyed his rare solitude, when he indulged himself with a good pipe, his violin, his favorite moth-eaten sweater and sneakers without socks.

During his last winter in California, Einstein was nearly hit by a car as he walked to campus. At his wife’s insistence, the couple moved into a suite at Caltech’s Athenaeum. The posh private faculty club, a kind of pub for Nobel laureates, had been built three years earlier to attract and nurture these geniuses.

Einstein’s suite, No. 20, is marked with a distinctive door -- mahogany instead of white like the rest. Einstein’s sponsor, Fleming, had built it as an apartment for himself.

Einstein was lecturing at Caltech when the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933. He realized he needed a safe haven to conduct his work, and offers came pouring in.

Caltech’s president, Millikan, agreed to hire him, but reportedly offered a paltry amount.

While Einstein was thinking over several offers, Princeton University asked what salary he wanted. Einstein reportedly said $3,000 per year. His wife stepped in and renegotiated it to $15,000.

Millikan pleaded with him to stay, to no avail. Einstein moved to Princeton in 1933, where he stayed until he died in 1955.

Sometimes Einstein seemed to lose sight of the respect he had inspired. Late in life, he described himself in a letter to a friend as “a lonely old fellow ... a kind of patriarchal figure who is known chiefly because he does not wear socks.”

Today, schoolchildren are more familiar with his formulas than his footwear.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.