King of the spec houses

Security guards, electric gates and high stone walls shield Beverly Park from intruders. Yet from a plateau high above the Beverly Hills Hotel, it is possible to look down on it, to have an aerial view of one of the most exclusive residential developments in the world. There’s Sylvester Stallone’s huge hacienda, Denzel Washington’s formal French chateau and the gargantuan showplace that octogenarian media mogul Sumner Redstone bought not long ago for his new bride.

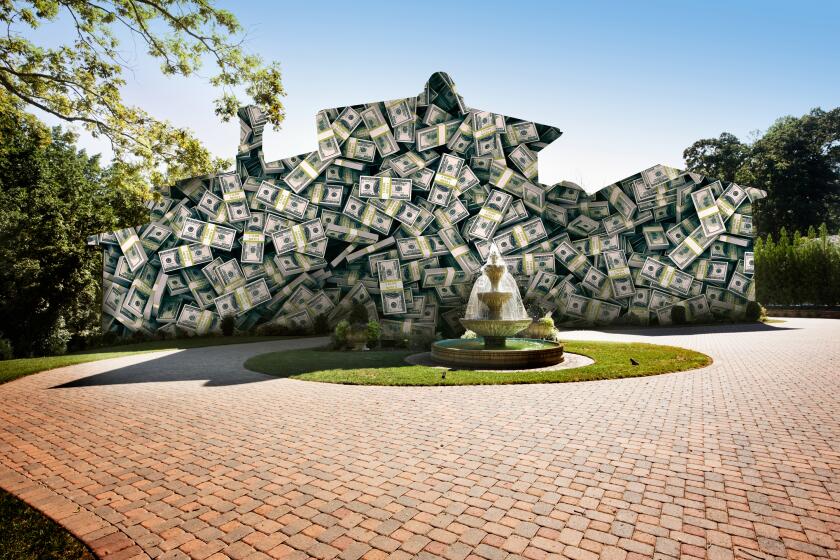

Past Paul Reiser’s beautifully landscaped tennis court, beyond the palace-in-progress Eddie Murphy’s waiting to move into, and beside the guest house being added to billionaire Haim Saban’s vast compound lies a grand Mediterranean villa. On the last day of September, 80 Beverly Park opened its 18-foot front doors, welcoming Realtors for the first time. While the neo-Tuscan mansion contains a media room with a screen that descends from the ceiling at the push of a button, a distressed marble kitchen island the size of a small bedroom, an elevator with a floor of Italian travertine, 11 bathrooms and seven bedrooms that open onto balconies tickled by vines of blooming bougainvillea, the cappuccino stucco house lacks the one thing that will make it a home. Number 80, built on spec and now on the market for $19,750,000, needs an owner.

How many house hunters are willing and able to adopt a nearly $20-million spec house? Well, this is L.A., so the answer is quite a few. According to the Wall Street Journal, sales in the Los Angeles luxury market, where the median home price is $1.25 million, were up 18.4 percent in the first half of this year. In the metaphoric neighborhood where prices are only a couple of digits shy of a telephone number, the platinum club of shoppers looking for homes priced above $10 million includes at least two dozen members, and they can choose from an inventory of 30 estates in Beverly Hills, Beverly Hills Post Office, Bel-Air, Holmby Hills, Brentwood and Pacific Palisades.

The morning of the new house’s public debut, Realtors Brian Adler and Mauricio Umansky, wearing elegant dark suits and cheerful ties, stood under the barrel-vaulted ceiling in the entry hall, ready to greet any professionals who had seen the listing in the Caravan Express brokers’ guide to Tuesday showings on the Westside. In 1979, Adler assembled a group of investors to buy the 325 virgin acres that became Beverly Park, and he’s been involved in the development, where he lived for 17 years, ever since. With little prompting and a salesman’s enthusiasm, he will extol the virtues of the enclave or the charms of Number 80. Visitors will have to imagine how the empty house will look once a decorator helps new owners spend $4 million to $8 million on furnishing and appointing the interiors. For now, Adler has borrowed one round antique wooden table to place in the foyer, and set a voluptuous orchid plant on it.

Umansky is a broad-shouldered, curly-haired man in his early 30s who dropped out of USC to start a clothing business, sold it eight years later, then looked for a new career. He found one in real estate and now concentrates on multimillion-dollar residential sales. In the last two years, 14 properties on the Westside went for more than $10 million; Umansky was involved with six of them. “I know who all the people are who are looking in the upper price range,” he says, “and anyone would recognize their names.” So he wasn’t surprised that he and Adler, who share the listing for Number 80, were asked to sign nondisclosure agreements by some people who expressed interest in touring the house as it neared completion. “They don’t want anyone to even know they’re looking,” Umansky says.

How the rich spend their money can arouse as much curiosity as their sex lives, so conglomerate chieftains, studio presidents and movie stars take some pains to keep their major purchases private. That effort can seem a tad disingenuous, however, because part of Beverly Park’s appeal is the status of the address, the cachet that accrues because everyone who’s anyone knows the price of admission. Tom Thompson of JLA Realty brought a couple he describes as “in the entertainment industry” to see Number 80. “They’ve been looking for six months in Holmby Hills and Bel-Air,” he says, “but those areas don’t have the prestige of Beverly Park. You tell someone you live in Holmby Hills, that doesn’t say a whole lot. It’s prestigious, but you could be in a $40-million home or a $2-million home. If you say you live in Beverly Park, everyone knows what that means.”

It means a whopping property tax bill, but that isn’t likely to panic the eventual owner of Number 80. The house across the street, for example, was purchased 2 1/2 years ago by former bodybuilder Bill Phillips, who sold controlling interest in his nutritional supplement business for an estimated $160 million and made more millions from a bestselling book of health advice. By the time he’d spent around $5 million furnishing his $15-million Moorish manor, he had probably sunk less than 20 percent of his fortune into his homestead, a fraction even Suze Orman would have trouble quibbling with. Umansky says: “During the Internet boom, when everyone was making crazy money, people were cashing out for $50 million and were ready to spend $20 million of it on a house. If we get a call from a broker to show Number 80, we ask who the client is. If it’s someone we know from the Forbes 400 list of wealthiest Americans or a celebrity who makes $20 million a movie, then showing it is automatic. If we don’t know them, we ask what their business is.”

By the time a prospective buyer makes an offer, the Realtors expect to see proof of funds from a private bank reference. In this bracket, Umansky says, seven out of 10 sales are for cash, so mortgage brokers and lenders are out of the loop.

Yet even among the house-payment-free, price matters. Another spec house that overlooks the Bel-Air Country Club costs the same as Number 80 and has been on the market for over a year. The developer has rejected offers of $15 million and $17 million. “Most of these people didn’t get to have hundreds of millions of dollars by being easy with their money,” Umansky says. “They have business managers and accountants who analyze deals for them. If they feel they’re overpaying, they’ll probably pull out.”

Love can overwhelm common sense. “If the emotional connection with a house is there and they really want it, they’ll pay the price sometimes, even if they know they might be overpaying by $1 million. But if the price seems $3 million too high, they can easily decide they aren’t really that much in love,” Umansky says.

THE SEDUCTION

It is Mauricio Oberfeld’s business to know what will make an affluent buyer lose his heart. The developer of Number 80, he was raised with a strong work ethic in a privileged precinct of Mexico City, a place ripe with promise when his grandfathers emigrated from Poland in the 1930s. He moved to L.A. with his family when he was 13 and lived in his parents’ home in Beverly Park while attending the USC School of Architecture. Barely out of his teens when he began developing high-end spec houses, he finished his first Beverly Park spec mansion when he was 25. Now 32, Mo, as his friends call him, favors dress shirts open at the neck, tailored slacks and the sort of round-faced, oversized watches you’d expect to see on a Formula One driver. He and Umansky share a first name, a love of golf, a focus on family life and a long friendship.

“My father bought four lots in Beverly Park in the early ‘90s,” Oberfeld says. “We sold one immediately, bought another one. I took one and developed it. My father owned and ran the Bank of Beverly Hills for a number of years, and I worked there when I was in school. There are things I could not have done without the help of contacts I met through him. What counts is what I do with it. My father and his brother quadrupled the business their father had been successful with. That’s my ambition -- to work as hard as I can, take what I was given to start with and multiply it tenfold.”

Oberfeld doesn’t circle opulence timidly, rather faces it head on, armed with the conviction that several levels of taste separate excess from elegance. He has a close enough relationship with restraint to have considered moving into a modern glass and plaster box down the hill from Beverly Park that was in construction at the same time as Number 80, a spec house he sold for just under $6 million six months after it was completed. A comic actor with a string of hit movies bought the home Oberfeld’s parents had lived in for 10 years, so during Number 80’s three-year gestation, he built them a new Mediterranean villa and supervised another spec house, both a canyon away in Beverly Ridge Estates. With his partners in the design and project management firm Dugally-Oberfeld LLC, he is involved in the development of eight homes in Orange County, one for retired home run king Mark McGwire. Altogether, Oberfeld has built 30 houses, a dozen on spec.

Aleck Dugally, the eminence grise of the firm, has been building homes in Southern California for 50 years, and is still in charge of design development for all the company’s projects. When he suggested a different look for the pool at Number 80 late in the construction process, Oberfeld first resisted, then ran with the concept and agreed to go $60,000 over budget to engineer separate wading and spa pools on either side of a raised rectangular pool framed with wide stone ledges. It was Dugally who made the first sketch of the facade of Number 80, in February 2000, on a flight to L.A. from Florida, where he’d gone to check on the progress of a home being built for an heir to the Ford Motor Co. He drew a long, linear, symmetrical structure influenced by the flamboyant Mediterranean revival style that architect Addison Mizner popularized in Palm Beach in the 1920s. Beneath the drawing, detailed with multiple arches, stone balustrades and narrow, peaked chimneys, he wrote, “The Romance of 80.”

In three dimensions and living color, Number 80 is romantic enough to be the setting for a perfume commercial, but prettiness is only part of the story. Oberfeld understands that the right suitor for the house will most likely be seduced by a combination of craftsmanship and the peculiar gestalt that bigness begets. Number 80 spans 19,040 square feet, with another 4,189 square feet of terraces and sleeping porches. “There are homes half the size of Number 80 that have the same number of rooms,” he says. “I don’t believe a big house should have 25 rooms. I believe in very large spaces. Little rooms only complicate a plan, and people don’t want them. People who buy this kind of home want to entertain and show off. We paneled the library on the first floor with mahogany, and that isn’t a very big space, so it’s intimate. But if a room is too intimate, it isn’t as impressive.”

The median American home is about 2,000 square feet. Houses with master suites twice that size dot the Southern California landscape, but not every jumbo pleasure palace captures the mood of the superlative mega-mansions, with their lobby-like entries and public rooms meant to effortlessly swallow 100 guests. “At 10,000 or 12,000 square feet, you can have a beautiful rich person’s house, but it isn’t necessarily the trophy estate,” Umansky says. Something happens north of $15 million, a grandeur and scale that make certain houses resemble embassies.

It is obvious that the robber barons and merchant princes who built stately private homes at the beginning of the last century were styling themselves as American royalty. How does someone attracted to the trophy houses of Beverly Park see himself? “The Big Cheese is on the phone,” Mrs. Sumner Redstone told a reporter from Forbes magazine who had come to interview her husband. More than designer clothes or limited-edition cars, and certainly more than jets or jewels that few friends get to see, an important house is a personal billboard that, in a land ruled by marketplace values, displays an incontestable message.

Today’s spec houses also offer instant gratification in exchange for a tolerable loss of control. When a new house is built, a never-ending series of decisions must be made, and the choices are more numerous in a home as extensive as Number 80. Should the sink in the downstairs powder room be marble or onyx? Would a fireplace of textured plaster or natural stone make the family dining room sing? “Most people don’t have the patience and the time to build a house,” Oberfeld says. “A movie star who goes away on location or a businessman who flies around the country and is too busy to be available can’t do it. Half the married couples you know would probably get divorced if they built a house.”

Oberfeld is more aesthetically consistent than many clients would be, than the sort of person who would insist on a chrome and glass bedroom as antiseptic as a laboratory even in a home modeled after Blenheim Palace. The developer chose a neutral palette, tones of honey, butterscotch and caramel, that leaves little for a buyer or interior designer to hate.

“We put a lot of money into our marbles and bathroom finishes, so those usually aren’t changed,” he says. “Still, some people might walk into the house and love everything about it but decide that they don’t like the color of the marble in the lady’s bathroom. And they’ll rip it out.” Said ripping could be a $100,000 decision. Oberfeld spent $40,000 on carpet, using gentle shades from cream to khaki. He expects a buyer will spend $50,000 or $60,000 replacing it. An owner might want to add an exterior stairway to an upstairs room that could serve as a gym, so a trainer could enter it directly, without having to walk through the house. Whatever. Some changes can be anticipated. A mature mulberry tree grows out of a medallion of flowers in the motor court. But before the artful mix of pebbles set in stained concrete bordered by ribbons of faux stone were installed, the area was equipped with underground pipes, just in case someone might prefer a fountain to a tree.

Although much of the money Oberfeld spent is on the screen, as they say in the movie business, an interested buyer still might ask, “Why does it cost so much?” A house like Number 80 is one of the last products in this consumer culture still made almost completely by hand. Some 2,000 workers were employed under the umbrellas of 100 subcontractors. On a slow day, 20 people worked on the house and the grounds. Most days, during the 18 months of construction, 200 were on the job from 7 a.m. till 5 p.m. The crews came from Simi Valley, Orange County, Ventura and the San Fernando Valley. Six days a week, construction superintendent Travis Roderick left the 1,900-square-foot house in Oak Park where he lives with his wife and three children and drove 45 minutes to the job site. “A lot of what I do is just baby-sitting,” he says. “In a house this size, you have three different painting companies working at once. Egos get in the way.” The biggest challenge, Roderick says, was finding craftsmen who understood and could accomplish the time-consuming, counterintuitive goal of making something brand-new look old.

Instead of putting a high gloss on walnut floors that took a month to sand, stain and polish, a matte finish was applied, giving a burnished look normally produced by years of use. “If you walk through the streets of Italy,” Oberfeld says, “you’ll see places where plaster has peeled off exterior walls and you can see brick underneath it. We don’t have 100 or 200 years to let that happen, so we create that effect on the wall around the property.” Making plaster appear aged is a six-month process of hand sculpting with smooth trowels, rake trowels and sponges. The look of a worn, faded roof is achieved by randomly setting seven shades of clay tile.

“If you really took a country house out of Tuscany and put it here, nobody would buy it. The rooms are tiny and the ceilings are low,” Oberfeld says. “We have contacts in Italy who help us buy gates and old fireplace mantels. Some of what they really used to use, you’d never put in your house. An old fireplace mantel really just looks decrepit and old. Some French and Italian antiques are amazing, but many of them you wouldn’t pay two cents for. We want this house to look as if it’s been here for a long time, even though it has the comforts of a new house.” Patina above, pre-wiring for telephone, satellite, security and computer network connections below.

THE WAIT

Realtors say a house like Number 80 will usually sell in four months to a year. The clock doesn’t tick as loudly for Oberfeld as it might, because he got a great deal on the lot when he bought it three years ago and raised equity from private investors, who look for a return on their investment rather than the monthly interest charges a bank collects. Until a buyer is found, he’ll pay carrying charges for a loan, the wages of gardeners and a cleaning crew, property taxes and a $2,000-a-month water bill for keeping 38,000 square feet of fresh sod green.

He was nervous when he built his first spec house 10 years ago, but he has since gained a measure of cool. “I’m not worried,” Oberfeld says, “because the market has been going up the last few years. Our equity in the lot is our profit margin, and that’s a good position to be in. We didn’t want to get to the end and have to sell at a reduced price because we couldn’t afford to wait six or eight months for the right buyer.”

In the week following the open house, eight buyers walked the 178-foot hallway, from one end of Number 80 to the other. A few returned several times.

“The reaction has been extremely positive,” Adler says. “This home could sell quickly. It could be in escrow in the next 45 days. I’ve had discussions with people who’ve said they’re very interested. But until you have a check in your hand, it’s all just conversation.”

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Thinking big in Beverly Park

A multimillion-dollar house is more than the sum of its parts. About those parts....

How much?

2-acre lot in Beverly Park, $7 million to $9 million

50 sets of plans at $500 per set = $25,000

100 workers’ passes issued by Beverly Park security at $20 each = $2,000 a quarter, $6,000 a year

Drainage system, with subterranean moat, $200,000

Landscaping, $750,000

How many?

Fireplaces, 5

Toilets, 13

Capacity of elevator, 4 adults

Capacity of wine room, 1,700 bottles

Steps from master bathroom to front door, about 65 (time elapsed, 36 seconds)

How big?

Front doors, 18 feet tall, 700 pounds each

Kitchen island, 8.5 feet by 12 feet

Screen in media room, 15 feet wide

Heating and air-conditioning system, eight zones, 34 tons of digitally controlled air

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.