The Philadelphia story

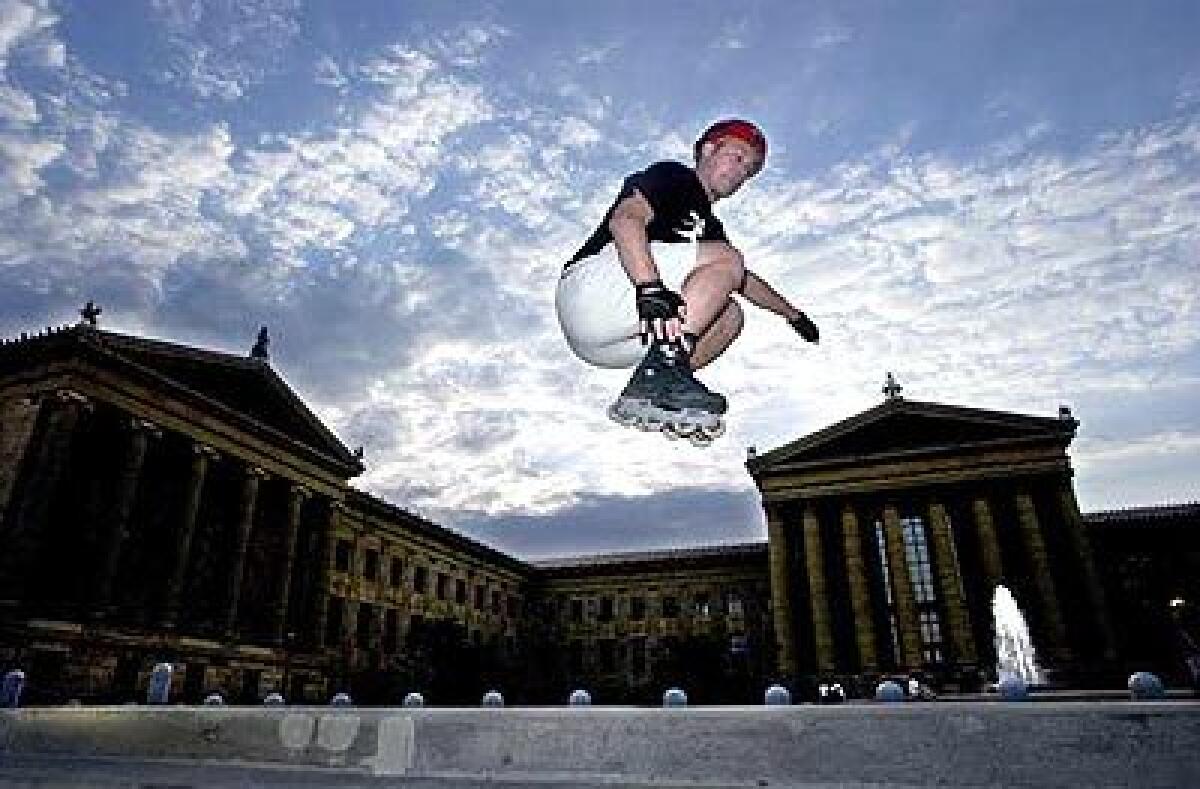

Philadelphia — There’s not much of a barrier between Philadelphians and their city’s history and culture. They walk briskly past the Liberty Bell on their way to a food-cart lunch, skateboard recklessly down the 100 steps of the Philadelphia Art Museum and, if you ask for Ben Franklin’s house, direct you by way of their more familiar gaudy red-white-and-blue landmark store, the Shirt Corner Plus.

So when Edward Becker looked out his office window and saw that Chestnut Street between Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell Pavilion was blocked for security reasons after Sept. 11, he resolved to do something about it.

Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell are part of Independence National Historical Park, a warren of old buildings important during the several decades in the late 18th century when Philadelphia was the nation’s capital and the pantheon of great Revolutionary Americans trod these streets daily, writing Declarations and Constitutions. Becker, like me, is a native Philadelphian, and we never tire in our defense of our town’s historical importance, no matter what blowhards from those upstart burgs, New York and Washington, say. We especially didn’t like that some bureaucrat in D.C. had closed one of our streets.

“People walk on that street to work and to go get a sandwich,” said Becker, who has long walked Chestnut Street — just as his heroes George Washington and Thomas Jefferson did — on breaks from the U.S. 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals, for which he is chief judge. To Becker, this was an attack on the very liberty and freedom Independence Hall and its surrounding buildings represent.

“John Adams and Ben Franklin walked around and had debates here, and now we couldn’t,” he said.

Becker, some merchants and residents browbeat the National Park Service and Philadelphia Mayor John Street into opening Chestnut on April 1, so now when tourists come to Philadelphia, they’ll be able to wander freely down the street, debating like Adams and Franklin or getting a cheesesteak from a cart.

Philadelphia is the antidote to Washington’s massive monuments and New York’s overwhelming commerciality. Most tourists drop into the city on a day trip between Washington and New York, see the Liberty Bell and tour Independence Hall and neighboring Carpenters’ Hall, where the Continental Congress met. We natives think that’s a darn shame, because most of Philadelphia’s attractions are wedged between residences and commercial activity, and many are small, quaint and as endearing to the locals as they are touristic. Few Philadelphians can pass 5th and Arch streets without throwing a good-luck penny through the grates of Christ Church Burial Ground onto Ben Franklin’s grave.

A block north of Franklin’s grave is the city’s latest historic site, the National Constitution Center, which was to have opened Friday. Locals like me are often skeptical about new things with lots of opening hoo-ha and interactive whatnots. But I grudgingly admit that the National Constitution Center isn’t a bad way to catch a little patriotic action.

The centerpiece of the place is a theater in the round, where actors and projection movies tell the story of the rights the Constitution preserves. Surrounding that on an upper floor are a dozen small theaters, computerized exhibits and docents who help examine parts of the Constitution, what it says and, sometimes more important, what it doesn’t say. Unlike many of the attractions in Philadelphia’s historic district, it is not free and government-owned; it’s private, and it charges admission ($6 for adults and $5 for children, seniors and college students).

While the Chestnut Street controversy festered, the two blocks north of Independence Hall were being ripped up, one for the Constitution Center and the other for a new pavilion for the Liberty Bell. As construction on the pavilion was started, historians discovered that part of it would rest on land where Washington’s slaves may have lived during his presidency. Here, between Independence Hall and a new center for the study of the Constitution, whose 13th Amendment abolished slavery, would be this landmark of a shameful part of our history. But as anyone who has seen a Philadelphian boo the home team at a sporting event knows, locals almost relish embarrassment. Builds character.

Instead of ignoring the Washington slave controversy, Philadelphians incorporated it into the National Park Service site. When the pavilion is ready next year, visitors will be able to muse for themselves on the irony of American slavery while gazing at the Liberty Bell.

I’ve always loved how my city celebrates its famous in less grandiose, sometimes goofy ways. When the government wanted to rebuild Ben Franklin’s house off Chestnut Street for the Bicentennial in 1976, it ended up with a metal superstructure of the house. Its open-air visage looks down on the excavation of the original 18th century building. My daughters make a beeline to “Ben’s potty,” the remains of his privy.

Two floors below is perhaps the Park Service’s most idiosyncratic site — the Franklin Underground museum — with offbeat dioramas of his diplomatic forays to France and England, a model of his glass harmonium and a bank of old Princess phones where you can “call” famous people, such as Jefferson or Lincoln, and they will tell you what they think of ol’ Ben. And as in Memphis, Tenn., where there are multiple Elvises, in Philadelphia several actors roam the historic area as Franklin. They spout “Penny saved, penny earned” aphorisms on cue.

Yet the historic area isn’t some gussied-up Williamsburg; it’s the place where we live. The cobblestone streets are authentic — in fact, Philadelphians’ car suspensions are probably the worst in America. We live and work in nifty 18th and 19th century town houses. If you get into one of the horse-drawn buggies that slow traffic in the area, don’t be surprised if the driver’s narratives are interrupted by a car horn and a few choice epithets. We have lunches to buy and places to go here, buddy.

But that’s the charm of Philadelphia. It is a city to live in. It’s not that we don’t appreciate tourists — I’ll bet we are the best around at giving directions and showing you how to avoid local rip-offs — but we are loud and boisterous and love our town.

The 20 or so square blocks around Independence Hall are crammed with at least three dozen museums, historic houses and other interesting sites. The vest-pocket nature of the sites around Independence Historic National Park means there is always something next door — an art gallery, a deli, a furniture store, a tie shop. Down the block from the Betsy Ross House (where Betsy may or may not have sewn an American flag) is, appropriately, Philadelphia’s flag-distribution district. Not far away, 300-year-old Elfreth’s Alley, America’s longest continuously lived-on street, bisects the city’s restaurant supply district. Within three blocks of Independence Hall, ethnic museums abound: the National Museum of American Jewish History, the Polish American Cultural Center and the African American Museum.

My dad was known for guiding me to the more obscure and/or out-of-the-way Philadelphia sites. A favorite of his was the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier of the Revolution in Washington Square, catty-corner from Independence Hall. There is an ever-burning flame and a statue of George Washington by the tomb.

Northwest across town a mile or so is another of Dad’s favorites. If you stand in the lobby of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which heads Ben Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia’s Champs-Elysées, you can see the work of three generations of Calders, the renowned family of sculptors. In the museum is one of Alexander “Sandy” Calder’s mobiles. Down the parkway a few blocks southeast is Logan Square fountain, whose sculptures were done by Alexander Stirling Calder, his father, and a few blocks farther is the French Renaissance Revival City Hall, topped by a statue of William Penn done in 1891 by Alexander Milne Calder, Sandy’s grandfather.

I have managed to do Dad one step better, dragging my daughters to the city’s wonderfully offbeat, and sometimes downright bizarre, museums. Though I am a big fan of Independence Hall, it’s these quirky places that make Philadelphia fun.

Sylvia, my 8-year-old, prefers the Philadelphia Doll Museum on North Broad, with its more than 300 black dolls, from 18th century slave-made cornhusk dolls to figurines of Muhammad Ali and “The Cosby Show” kids.

The Rosenbach brothers compiled a world-class collection of Egyptian statuary, miniature oil paintings and, primarily, manuscripts. On display in the Rosenbach Museum & Library, their 1860s town house, are such items as Lewis Carroll’s copy of “Alice in Wonderland,” the oldest letter of Washington’s that is known to exist (he wrote it at 17), James Joyce’s handwritten copy of “Ulysses” and a re-creation of poet Marianne Moore’s Greenwich Village living room.

Then there is the eerie Mütter Museum on 22nd Street, the one place I haven’t persuaded my kids to visit. The museum, started by 19th century Philadelphia physician Thomas Mütter, has grown into one of the largest caches of medical oddities one can imagine. Look one way and you’ll see the death cast of Cheng and Eng, the original “Siamese twins.” Look another, and there’s a 10-foot enlarged colon, horns taken from human heads and a wall of diseased body parts in jars. The collection also has body parts excised from the famous: a hunk of John Wilkes Booth’s neck, Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall’s bladder stones, a piece of President Grover Cleveland’s cancerous jaw.

If you like the Mütter, then go on, please, to the Shoe Museum, at the Temple University School of Podiatry, three blocks north of Independence Hall (don’t miss Betty Ford’s dancing slippers); the Dental Museum (scores of pulled teeth); and the Philadelphia A’s Museum (memorabilia from a baseball team that sneaked out of town — to Kansas City, of all places — in 1954).

In Philadelphia we honor our own, no matter how obscure. Besides the long-gone A’s, we have a museum dedicated to post-World War II operatic heartthrob Mario Lanza, who left town when he was in his early 20s, and another to black actor-singer Paul Robeson, who didn’t even move here until he was in his 60s. Near the Paul Robeson House Museum on Walnut Street in West Philadelphia is a mural depicting him at the height of his fame in the middle of the 20th century.

It is one of 2,100 murals in town. The Philadelphia Mural Arts Program was started as an anti-graffiti initiative in 1984, and its pieces pop out at you wherever you wander. I’m fond of the three-story mural of basketball legend Julius Erving, not in a basketball uniform but in a tailored suit, on a wall on Ridge Avenue in a dilapidated industrial district a few blocks north of the Center City neighborhood.

Philly native Larry Fine, the frizzy-haired one of the Three Stooges, overlooks the multicolored-and-Mohawk-haired crowd that wanders the hip South Street entertainment area. Jackie Robinson slides into home a few blocks from the site of old Connie Mack Stadium, taking revenge on the fans who booed him on his first trip here. Drive the treacherous Schuylkill (pronounced school-kill) Expressway near the Philadelphia Zoo (the oldest in America) and see the Rousseau-like animal mural. Or walk a block from the Avenue of the Arts, the stretch of South Broad Street with a half-dozen theaters, and see “Philadelphia Muses,” a homage to Maxfield Parrish.

And when you are all done with this, zip down to South Philly, where I lived for nine years, for what I consider the most European section of any city in America, the 9th Street Market. The mile-long stretch is commonly known as the Italian Market, though now about a quarter of the fruit, meat, cheese, fish, spice and knickknack vendors are either Southeast Asian or Korean.

Stop in at Sonny D’Angelo’s meat market for a side of buffalo or ostrich. Squeeze into DiBruno’s cheese shop for a smell and a taste of 100 cheeses and three dozen kinds of olives. Argue with a fruit vendor over which of you has the right to pick the peach he wants to sell you.

When you make it down to Wharton Street, see if you can solve the ultimate South Philly question: Pat’s or Geno’s. These outdoor cheesesteak places compete for attention 24 hours a day. A mural of Frank Sinatra, the patron saint of South Philly, looms in his “In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning” mode. Savor a cheesesteak and you’ll wonder why you were so hot to get to that mundane, musty Smithsonian in the first place.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.