Q&A; with Quincy Jones

For more than four decades, Quincy Jones, 64, has been one of the music world’s most respected figures, someone who exhibits in his interviews and speeches the same optimism and grace that have distinguished the recordings that earned him an unprecedented 26 Grammys.

So it was unusual this week to hear weariness and sorrow in Jones’ voice as he reflected on the recent murders that have robbed hip-hop of two of its biggest stars.

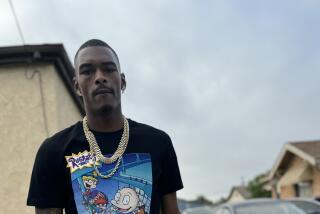

Tupac Shakur was shot in Las Vegas on Sept. 7 and Christopher Wallace, known professionally as the Notorious B.I.G., was slain March 9 in Los Angeles. Neither crime has been solved, though both are believed to be outgrowths of the artists’ flamboyant gangsta rap lifestyles and images. They were 25 and 24, respectively.

In the hours after Wallace’s death, Jones, who is founder and chairman of Vibe magazine, wrote a passionate editorial for the publication that condemned the “senseless” killings and called the gangsta lifestyle a “sad farce.” Jones, whose daughter Kidada, was engaged to Shakur at the time of his death, subsequently vowed to devote “the rest of my life” to ending the self-destructive elements of hip-hop.

Monday, Jones will join National Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences President-CEO Michael Greene in calling for a record-industry summit to address issues facing the hip-hop and rap communities. He already has lent his support to an effort organized by Def Jam Entertainment CEO Russell Simmons to create a “unity” album and tour involving rival East Coast and West Coast rap forces.

Unlike politicians and media watchdogs who have urged record companies to stop distributing hard-core rap, Jones doesn’t want to censor the music, which frequently speaks with an anguish and pain that updates the raw energy of classic blues. The aim, he said, is to open a dialogue between record labels, rappers and others to eliminate the “psychodrama” and other problems surrounding the music.

*

Question: This is such a complex issue, with social and economic ramifications. But, for starters, what can be done to stop the violence?

*

Answer: There’s no one answer. You try to do it in many ways. Everybody is trying to do something. I am trying to see if you can consolidate their energy . . . Michael Greene at NARAS, the rappers, Russell Simmons. I think that genuine concern should be put in one central place. We need a coalition of the hip-hop nation.

Q: What was your feeling after the deaths?

A: It was unbelievable. It hits so close to my family. But it’s not just something I’ve been concerned about recently. There have been other deaths. I went with LL Cool J to see [pioneer gangsta rapper] Eazy-E the day before he died [of complications of AIDS in 1995]. I wanted to show him that I cared . . . how much we all care. People were good to us when we were young . . . [Count] Basie, Duke [Ellington], Dizzy [Gillespie], people like that. They were very close.

That pattern follows in my whole life. I care about these kids. I’ve worked with them. My son is a hip-hop producer. My daughters are all into the music. Vibe magazine deals with it.

Q: Part of the tragedy of the violence in gangsta rap is that it comes at a time when hip-hop and rap music have achieved so much. Hip-hop is one of the most remarkable celebrations of life and African American culture in decades.

A: Absolutely. I guess hip-hop has been closer to the pulse of the streets than any music we’ve had in a long time. It’s sociology as well as music, which is in keeping with the tradition of black music in America. If you read the musicology books, you don’t always get the full story. But I’ve traced all this stuff down and done a lot of research on it.

After every war, there was a significant change in the music, and I can understand how that happened. If you participate in protecting the country, you think you can be part of it, but you come back home and it’s worse than ever. That has been going on since the Spanish-American War and before. Hip-hop is still spreading the message. This is almost like CNN, as [rapper] Chuck D says. . . . I’m a tremendous believer and supporter in hip-hop and rap . . . and you just can’t put everybody under that banner of gangsta. There are incredible people out there with incredible minds.

Q: What about Tupac? What was he like in your meetings with him?

A: Tupac was a very brilliant kid. I’ve seen screenplays by Tupac. I’ve seen his letters. I know someone who went to school with him, and he was one of the brightest kids in the school. . . . I think the playing out of the theater of [gangsta rap] is where everybody gets in trouble. You play gangster and stuff and you get burned.

Q: Do you think he could have eventually moved beyond the psychodrama, as you call it?

A: Yes, he had a mission to go past that. He said it to several of us. He was tired of the facade--and it was a facade. He was tired of playing the game.

Q: Is the much-publicized East Coast and West Coast feud real or just theater?

A: Well, they were ragging on each other in the records and so forth, but it was still theater. It didn’t get to the point where someone had to die, and I don’t think the deaths were a direct result of that.

Q: What is the role of record companies in this? Do they have a responsibility that goes beyond simply releasing records?

A: You’re damn right. If they participate in the profits of the music, they have a responsibility for it.

Q: What do you think of those who criticize rap and want to censor it?

A: They don’t know what the [expletive] is going on. It’s for attention or self-aggrandizement. To condemn hip-hop is to condemn two generations of our youth, and that’s a sweeping indictment that we can’t allow. That hurts the situation more than helps.

Q: After all these years and all the social struggles you’ve seen, are you an optimist?

A: You’ve got to keep going, man. What else do you do? Go under? I wouldn’t be devoting my time to this if I didn’t think positively. The community has got to get it together. We want to help these young people survive and live out their talents and dreams.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.