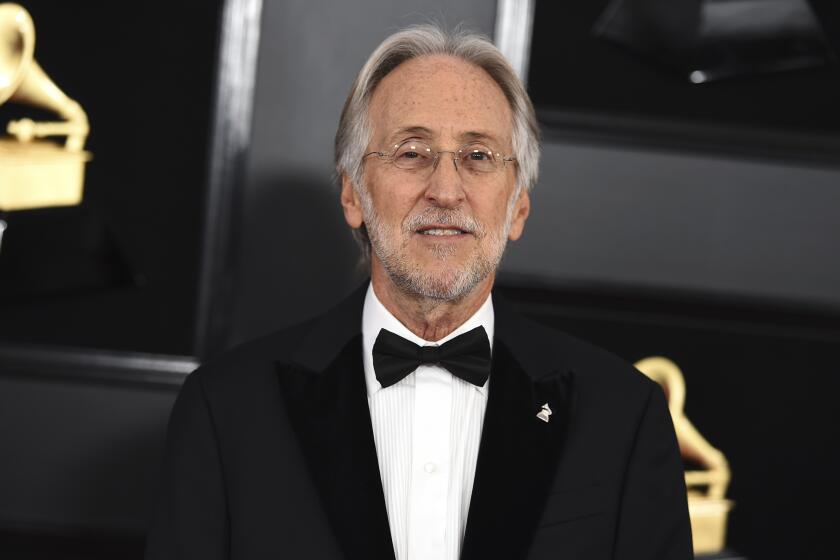

On Saturday, on the eve of the Grammy Awards, the Recording Academy will bestow its Trustees Award on prominent music industry attorney Joel Katz, a former chairman and general counsel of the organization who has represented Michael Jackson’s estate and Willie Nelson.

Not everyone thinks it’s deserved.

Terri McIntyre, the former executive director of the Los Angeles chapter of the Recording Academy, is troubled that the group will honor — alongside such past luminaries as Walt Disney, Berry Gordy and George Martin — someone she believes once played a key role in helping foster a culture of secrecy around allegations of abuse and harassment inside the organization.

McIntyre told The Times in an interview that, two decades ago, Katz offered her $1 million to remain silent about alleged sexual assaults that she said she had experienced while working at the academy.

The rule at the academy was, “Don’t speak about anything that happened within these walls.”

— Joanne Gardner Lowell

“He said that, for my time and my trouble and my changing careers, and for the good of the academy and for the good of me, that we could just stop this and make this go away,” she said.

In a recent lawsuit, McIntyre alleged that her then-boss, former academy President and Chief Executive C. Michael Greene, raped her. Greene — who resigned in 2002, a year after trustees paid another former female academy executive $650,000 to settle claims of sexual abuse — has previously denied allegations of sexual misconduct by anyone at the academy.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

A representative for Greene said in a statement, “Mr. Greene categorically denies Ms. McIntyre’s allegations and will vigorously defend against her spurious claims.“

McIntyre said Katz twice offered her money in exchange for signing nondisclosure agreements, including the $1-million offer she says he made in a phone call five years after she left the academy. She refused to sign the documents, she said.

“The only thing I had control over,” McIntyre said, “was not to be another cog in the wheel of silencing victims.”

Terri McIntyre, a former executive director of the Recording Academy’s Los Angeles chapter, alleges sexual assault and battery, negligence and harassment, and cover-ups.

A friend of McIntyre’s told The Times that in 2001 McIntyre spoke to them about Greene and Katz’s offer of a million-dollar settlement in exchange for signing an NDA about sexual misconduct.

“The Recording Academy has a zero-tolerance policy when it comes to sexual misconduct,” the organization said in a statement. “Over the last four years we have worked hard to change the culture and evolve our Academy in every way. Our focus is on the future and on our mission to celebrate, uplift, but most importantly serve our music community. We will continue to listen, change, and work to be better in everything we do.”

Katz did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

As it has made strides in recent years to change its culture and shed an image some have described as an “old boys’ club,” the academy is again facing questions over its accountability for past claims of alleged misconduct and abuse by former executives, according to interviews with about two dozen former Recording Academy employees, insiders and board members, and a review of recent lawsuits against the organization.

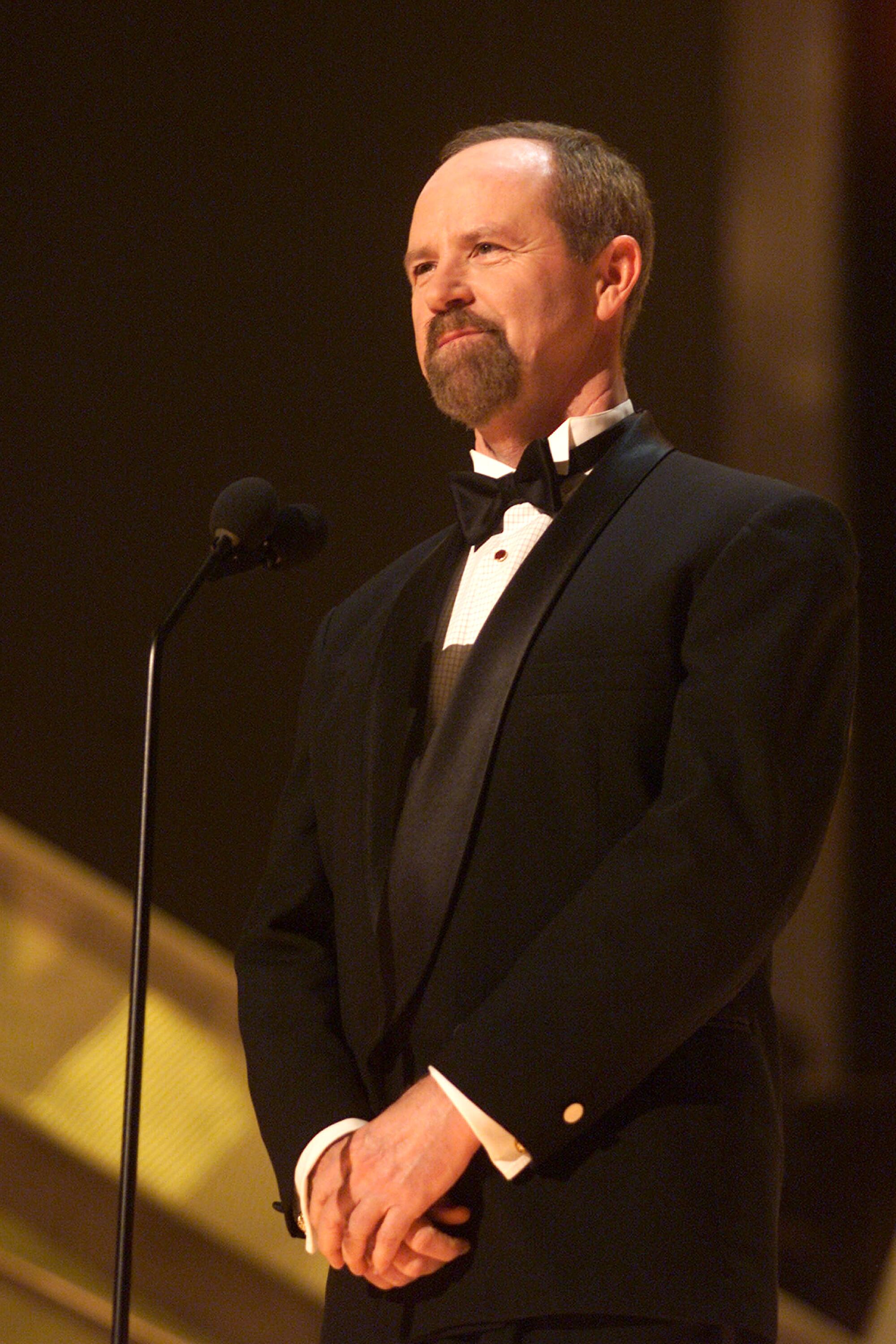

Those lawsuits, spurred by so-called “look-back” laws in New York and California, have renewed scrutiny of the academy’s handling of past sexual assault allegations against Greene and his successor, Neil Portnow. Both have denied all claims of wrongdoing.

The recent legal filings echo at least some of the allegations of harassment and self-dealing raised by former Recording Academy President and CEO Deborah Dugan, who was fired in 2020.

Since the mid-1990s, at least five women confirmed to The Times that they signed NDAs and received payments or settlements from the academy after raising claims of abuse or mistreatment.

“I don’t think you can ever forget the terror when you are that powerless,” McIntyre said.

When the academy hired Dugan to be its leader in 2019, it was supposed to mark a new era.

Dugan — a lawyer who had worked for Walt Disney Co., EMI Records and Bono’s Red charity — succeeded Portnow, who drew widespread condemnation over his comments that women needed to “step up” if they wanted to win Grammys.

Dugan was the first woman to lead the academy; she arrived with a mandate for change.

But the board of trustees terminated Dugan seven months later, citing “the evidence of two independent investigations” into her leadership.

The academy claimed Dugan had bullied her assistant and then demanded a $22-million payout to leave quietly, and placed her on administrative leave.

Dugan denied the claims and filed a 44-page complaint with the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, accusing her former employer of retaliating against her for bringing to light a slew of problems that had dogged the organization for years, including sexual harassment, flagrant conflicts of interest among board members and voting improprieties.

Dugan said that the board asked her to approve paying Portnow as a consultant for $750,000, and alleged in a complaint that his contract was not renewed because he allegedly had raped a female recording artist, one who sued him last year. She also accused Katz of sexually harassing her, which Katz denied.

In a statement, Portnow said Dugan’s EEOC complaint contained false and “terribly hurtful claims against me” and the rape allegations were “ridiculous, and untrue.” He said he was “completely exonerated” by an independent investigation. Portnow also denied that he ever “demand[ed] a $750,000 consulting fee.”

Dugan settled with the Recording Academy in 2021, avoiding arbitration hearings over her dismissal that were set to begin. She received $5.75 million, according to the organization’s 2022 tax filing. Dugan and her attorney declined to comment.

He offered me a million dollars and said that it’s for the good of the academy to put this to bed.

— Terri McIntyre

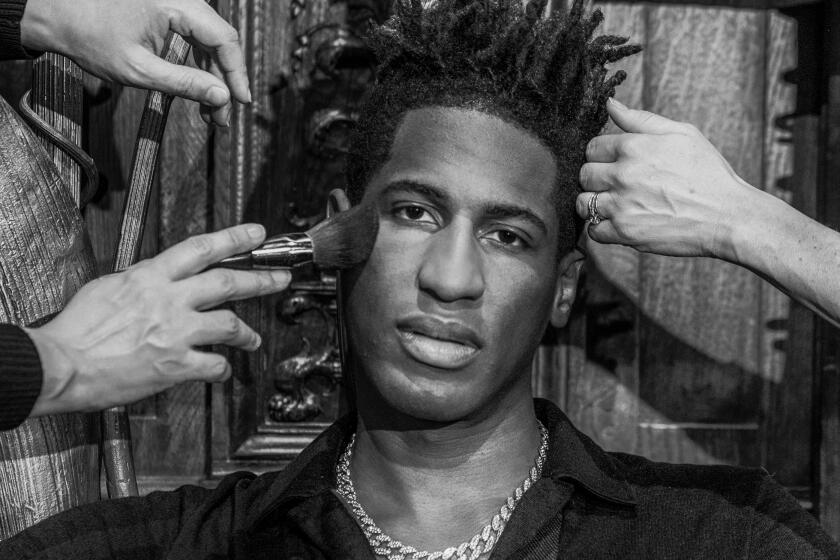

To repair the damage, the academy elevated Harvey Mason Jr., a charismatic music producer with decades of academy service, to the top job in 2021.

Mason took steps to diversify both the academy’s executive ranks and its voting membership of more than 11,000 recording industry professionals, in response to long-standing criticism that the organization overvalued the work of older white men.

Of the more than 2,400 new members who joined last year, the academy says half are people of color and more than one-third are women. The academy also eliminated the use of controversial secretive committees that shaped nominations for the Grammys.

“Our commitment to diversity and inclusivity, however, is an ongoing effort,” Mason said in a statement. “While we celebrate our progress, we also acknowledge that there’s still more work that must be done.”

Some effects of those efforts are evident. This year, seven of the eight nominees for album of the year are by women or nonbinary artists.

But for women like McIntyre, who allege abuses in previous eras at the academy, the organization still has not truly reckoned with its past, she said. One reason is the use of NDAs to keep claims of abuse and harassment, even those going back decades, secret.

In her December lawsuit, McIntyre alleges Greene twice raped her during her two years at the academy. The first alleged assault was at a 1994 Recording Academy trustees meeting in Hawaii, where Greene drugged and assaulted her at a hotel, according to the lawsuit.

During the second alleged incident, in late 1995 at Greene’s Malibu beach house, McIntyre alleges in her lawsuit that “Greene grabbed the back of her head with his hands” and “shoved his erect penis into Plaintiff’s mouth.” McIntyre said she tried to get away but Greene “maintained his firm hold” on her head as she “gagged,” the complaint states.

Because of Greene’s enormous power within the academy and the music industry, McIntyre knew “any report she made would effectively end her career. … He held the power to effectively block her from any further positions in the Music Industry,” the lawsuit states.

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Greene’s alleged conduct and demands of NDAs were common knowledge within academy leadership at the time, said Joanne Gardner Lowell, who reported to Greene as the academy’s senior director of special projects. She recalled Greene sharing vulgar stories of his sexual exploits during meetings.

An unnamed musician has accused former Recording Academy CEO Neil Portnow of drugging and raping her in a New York hotel room in 2018.

“The point was for people to be uncomfortable,” Lowell said. “When I did my paperwork he said I had to sign an NDA. I said, ‘Don’t do anything you don’t want to get sued over.’ The rule at the academy was, ‘Don’t speak about anything that happened within these walls.’”

Lowell, who did not sign an NDA, said that McIntyre, after she resigned, confided in Lowell about Greene’s alleged assaults and the academy’s attempts to silence her.

“Women still deserve to have someone say this was wrong,” Lowell said.

Greg Knowles, who spent 20 years on the academy’s board of governors and as its Los Angeles president, recalled a meeting with the trustees in the mid-’90s. When “the subject of Mike Greene came up,” he said, “there were a lot of NDAs. I made an appointment with Mike, and there were a bunch of attorneys with him that I didn’t know. He had a hold over everybody, people were afraid of him.”

The Recording Academy has a zero-tolerance policy when it comes to sexual misconduct.

— The Recording Academy

McIntyre’s assistant at the time, Patrick Gleason, said that she “never wanted to be in the office with Greene. She said, ‘I don’t like being around him. I never want to take photos next to him.’ She’d get panicky around him, her anxiety levels would spike.”

Some staffers spoke more highly of Greene. Former academy executive Dana Tomarken, who worked for MusiCares, the organization’s philanthropy arm, for 25 years and was hired by Greene, said she never observed him “ever misuse a woman in any way, shape or form.”

Yet Jill Marie Geimer, a former human resources executive at the academy, was hired to guard against potential harassment incidents after an internal inquiry into Greene’s alleged conduct.

While country and regional Mexican music both enjoyed record-breaking chart success this year, there’s little acknowledgement of those genres in the top categories.

Geimer’s claims were first detailed in a 2001 Times article in which she alleged “a year-long pattern of alleged physical and psychological manipulation by Greene, including violent outbursts and sexual abuse.”

Geimer reached a settlement with the academy and was paid $650,000, as The Times previously reported.

The academy said then that Greene had been cleared of wrongdoing by an independent investigation, and at the time Greene also described the allegations as groundless. A year after the academy settled with Geimer, Greene abruptly resigned and left with an $8-million severance package.

After Greene’s exit, the board in 2002 turned to Portnow, the board’s secretary and treasurer, to become the new president.

Portnow was a music industry veteran who had served in executive roles at 20th Century Fox Records, Arista, EMI America Records and the Zomba Group.

Critics charged that the organization under Portnow’s leadership became more corporate — and more white and male.

“The people in the room that made decisions were all white men,” said one former executive who asked not to be identified for fear of reprisals.

Portnow’s final years at the academy were filled with controversy.

In 2019, Tomarken, the former MusiCares executive, sued the organization, alleging that she was wrongfully terminated, in part for challenging an entrenched “boys’ club” mentality.

Tomarken accused Portnow of orchestrating a deal to hold MusiCares’ 2018 Person of the Year gala at a venue that caused significant financial losses, and said that Portnow tried to thwart her efforts to alert the board.

Portnow and the academy denied any wrongdoing and within months Tomarken settled the suit. Tomarken declined to comment, citing an NDA.

Portnow’s conduct was again questioned in a November 2023 lawsuit from an unnamed musician claiming that he raped her.

In the suit, filed in New York State Supreme Court, the woman said she met the former academy chief in June 2018 at a Grammy event, and that Portnow, 75, invited her to his hotel room. She alleges he gave her a drink that left her “disoriented and incapacitated,” and that Portnow raped her while she was slipping in and out of consciousness.

This industry is dominated by men and they have so much power over people.

— Nancy Erika Smith

The musician says that she reported the assault to the Recording Academy in 2018 but was never interviewed about it.

“Neil Portnow has repeatedly denied the false allegations against him and will continue to vigorously defend against these malicious and outrageous claims,” said his attorney Edward Spiro. “During his tenure at the Recording Academy, Neil Portnow had a strong track record of appointing women and people of color to management and leadership positions throughout the organization.”

Additionally, Spiro said the $750,000 payment referenced in Dugan’s complaint was “part of a deferred compensation agreement previously approved and authorized by the Board of Trustees; it was not a consulting fee.”

In a November statement, the academy said: “We continue to believe the claims to be without merit and intend to vigorously defend the Academy in this lawsuit.”

Beyond the settlements with former employees, the academy drew scrutiny for the high fees it has paid outside law firms, including Katz’s.

The academy paid Katz’s firm Greenberg Traurig $12.6 million for legal services between 2017 and 2021, according to federal tax returns. Katz left that firm in December 2020 and is now senior counsel at Barnes & Thornburg. He is listed as a board director emeritus of the Grammy Museum and serves on an academy advisory committee.

The academy paid an additional $10.95 million to the law firm Proskauer Rose between 2017 and 2022, according to the organization’s tax filings.

After leaving the academy, McIntyre had trouble finding work in the music industry.

In an interview, former Recording Academy CEO Deborah Dugan decries the “culture of secrecy” at the Grammys organization and says “change must happen.”

“I tried to stay in Los Angeles,” she said. “I’d had a successful career. I went back to people on my board and my trustees. ... They all said, ‘Terri, we’d love to hire you, but Mike Greene has made it known that we’re not allowed to hire you. He will make sure that none of our artists will make it onto the telecast.”

McIntyre and her young daughter moved into her mother’s home in Texas; she said she was forced to apply for minimum-wage jobs.

Yet she was determined, she said, to never take a settlement or sign an NDA.

McIntyre still recalls her final phone calls with Greene and Katz in 2001.

“I get a phone call from Mike Greene, and my physical response was that I started to shake,” McIntyre said. “He says, ‘Hey, Terri, how are you, kiddo? You know, with this investigation that’s going on, I think we could come to some type of agreement that would be good for you, good for the academy. We could just put this to rest.’”

A few days later, she said, Katz, a former chairman of the academy’s board of trustees, called her at her new job at Continental Airlines. He was named general counsel to the academy in 2002.

“He offered me a million dollars and said that it’s for the good of the academy to put this to bed. But there was never a moment that I considered buying into their cover-up,” McIntyre said. “I’m pretty proud of 20-something me for choosing to hold on to my dignity and my self-respect, choosing to not take their money.”

McIntyre’s husband told The Times that, in the mid-2000s, she told him about the alleged $1-million offer. In a 2017 Facebook post, McIntyre claimed the academy proposed several settlements, naming Greene as her alleged abuser. Additionally, Lowell said that last year, after the academy announced Katz’s award, McIntyre told her about his alleged role in offering a payout in exchange for an NDA.

Nancy Erika Smith, an employment and civil rights lawyer, best known for representing Gretchen Carlson in her $20-million settlement with Fox News chief Roger Ailes, said fears of retaliation leave victims in an impossible bind.

“This industry is dominated by men and they have so much power over people, it’s not like you can go somewhere else and get a Grammy,” Smith said. “Their power is phenomenal to make or break a person.”

‘It’s a long road to get to a transformative change like this,’ Recording Academy Chief Executive Harvey Mason Jr. told The Times.

Smith said the look-back laws have given many women, including those currently suing Greene and Portnow, the opportunity “to right an historical wrong by our culture. I’m glad women finally feel empowered for something carried for years.”

Alexa Nikolas, founder of the activist group Eat Predators, is planning a protest outside Crypto.com Arena, where the Grammys will be held, to challenge the organization’s use of nondisclosure agreements.

“I hope this protest highlights a disturbing pattern within the music industry: a long-standing history of covering up sexual abuse,” Nikolas said. “The path forward for the music industry must involve a shift from complicity to accountability.”

For McIntyre, true accountability from the academy would include a permanent end to any NDAs regarding claims of abuse or harassment — and not to honor someone she believed participated in a culture of secrecy.

“I had hoped they meant it when they said the academy now has a zero-tolerance policy,“ McIntyre said.

Times staff writer Mikael Wood contributed to this report

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.