Unrest Widens Rifts in Diverse Latino Population : Communities: Some leaders distance themselves from violence. Recent immigrants resent taking blame.

Devastating riots that swept Los Angeles last week have driven a wedge in the city’s diverse Latino community, widening the gap between hard-hit immigrant neighborhoods and traditional Latino leaders who were slow to respond to the crisis.

Though largely portrayed in the national media as a black uprising, the riots in fact involved many Latinos, both as victims and vandals. One-third of those killed and at least as many arrested for looting and other crimes were Latino; Latino-owned businesses were destroyed and many Latinos were left homeless by arson.

Elected Latino officials were quick to congratulate their Eastside constituency for restraint shown during the violence; very little looting was reported east of the Los Angeles River.

They appeared equally eager however, to distance themselves from what some officials called the less stable Latino enclaves of Pico-Union and South Los Angeles, which are populated by more recent immigrants and which were caught in the eye of the firestorm.

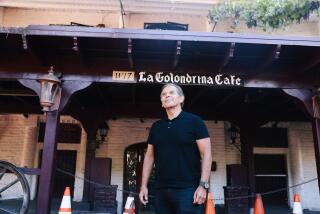

The early exception was City Councilman Mike Hernandez, who traveled to the Pico-Union district that he represents hours after the violence erupted and set up an assistance network. He was the first elected official to do so. During the subsequent 24 hours, he went on Spanish-language television and radio to urge calm among Latinos.

But he conceded that Latino officials, perhaps nervous about inflaming the complicated mix of ethnic tensions, were tentative and overly cautious.

“We were slow in coming out on the issue,” Hernandez said. “Politicians tend to want to get their 10-second sound bite. What we needed to do is roll up our sleeves and get to work.”

Most elected Latino officials, who for the most part trace their roots to Mexico, have little connection with newer, Spanish-speaking immigrant communities, many of whom come from Central America. And those immigrants show little faith in these leaders.

Their agendas and interests diverge, and because many newer immigrants are not citizens or came to the United States illegally, they do not vote.

“I try my best to be an advocate for (immigrants’) concerns,” said City Councilman Richard Alatorre, whose district includes Boyle Heights, El Sereno and other Eastside neighborhoods. “But I didn’t get elected to represent them. I have a responsibility to the people I happen to represent.”

Consequently, say immigrant advocates, the more recent arrivals from Latin America have been ignored in these days of painful post-riot recovery. Or, worse, they are shouldering the bulk of the blame for the chaos that ruled the city’s streets for three days.

“There are many Latino leaders who say they represent Latinos, but they do not represent all Latinos,” said Carlos Vaquerano, an official with the Central American Refugee Center.

Madeline Janis, executive director of the center, which is headquartered in the Pico-Union district, urged that all Latino leaders unite to support new immigrants in the wake of the riots.

“There’s going to be a big backlash now because immigrants are an easy target, and if we don’t have the established Latino leadership defending the rights of the newer immigrants, then we are going to be in an even more desperate situation that we are,” she said.

Janis experienced the backlash when she appeared on a live radio talk show Thursday. The seven or eight calls from listeners that she fielded advocated sending immigrants back to where they came from, she said.

Looting and destruction were heaviest in immigrant neighborhoods, experts say, because there is little political or social attachment to the area.

“It did not happen in East L.A., Wilmington . . . areas that are just as poor but which have a different, stronger sense of community, a stronger attachment to their neighborhood,” UCLA demographer Leo Estrada said.

“These people are more likely to own their own homes. . . . Everybody said, ‘How can they destroy their neighborhoods, their jobs. . . ?’ Well, my answer is that they did not consider it to be their own.”

Nevertheless, rioters were selective, avoiding churches and social service agencies, said Estrada, who was a member of the Christopher Commission, the blue-ribbon panel that investigated the Los Angeles Police Department after the beating of Rodney G. King.

Latino-owned businesses in South Los Angeles and in Pico-Union were heavily damaged. While a full accounting has not been made, state officials believe at least 30% of the estimated 4,000 businesses destroyed belong to Latinos. “And I would not be surprised if it went substantially higher than that,” said state Sen. Art Torres (D-Los Angeles).

In addition, 19 of 58 people killed in riot violence were Latino, and hundreds more were injured and left homeless. More than 500 newsstands and kiosks that sell the city’s major Spanish-language newspaper, La Opinion, were destroyed, according to editors of the daily.

In contrast, the Eastside was largely quiet. Only 10 businesses were looted in a 15 1/2-square-mile area, and much of the booty from a Sears store was returned when parents realized what their children had done. No fires or other acts of violence were reported, and only 70 National Guards troops were deployed there.

There were signs Thursday that some effort is being made to bridge the gap between the newer and more established communities. The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) sponsored a meeting Wednesday night--a week after the riots erupted--with Los Angeles County Supervisor Gloria Molina and representatives of the Central American community, among others, who discussed emergency aid.

“There’s a realization we have to strengthen our ties with the newer immigrant community,” said Antonia Hernandez, president and general counsel of MALDEF.

Molina’s office did not respond to queries.

The immigrant community has also been alarmed over actions by the police this week. In violation of longstanding policy, Los Angeles police officers who arrest illegal aliens on suspicion of looting or other riot-related crimes are turning suspects over to the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service for probable deportation.

According to the INS, illegal aliens accounted for more than 1,200 of the nearly 15,000 people arrested in the riots.

Of 477 illegal aliens picked up and handed to the INS, 360 are from Mexico; 62 from El Salvador; 35 from Guatemala; 14 from Honduras; two from Jamaica and the rest from other countries, according to the INS.

About 300 of these already have been bused back to the border and deposited in Mexico. In addition, the INS has another 784 aliens it will turn over to federal authorities once the police or sheriff’s departments dispose of their cases.

Hoping to counter those who would blame the entire Latino community for the acts of arsonists and looters, the governments of Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras joined Thursday to ask Mayor Tom Bradley to “respect immigrants’ human rights.” Such respect must come, the governments said, “regardless of their migratory status.”

By no means were blacks and Latinos the only participants in last week’s mayhem. The ethnic breakdown of the arrested shows whites and Asians also joined in the fray.

“In the history of our cities, this was our first multiethnic riot,” Estrada said. “Once the looting got started,” many people from all ethnic groups joined in.

According to many accounts provided during the riots and in their aftermath, Latinos did more looting than burning. In interviews, Latino looters said they acted out of anger at the system and at years of discrimination. More than a response to verdicts in the trial of officers charged in the King beating, many said they were taking advantage of the anarchy to share in the wealth.

Los Angeles police said almost half of the people arrested by the agency from midnight April 30 until Monday morning were Latino. Of 5,438 people arrested, Cmdr. Robert Gil said, 2,764 were Latino, 2,022 black, 568 white and 84 classified as other.

Sheriff Sherman Block provided a breakdown of some of the 4,018 arrests by his department during the same period. Of the 1,628 arrests categorized by Block, 810 were black, 728 Latino, 72 white and 18 classified as other.

Neither agency gave any breakdown by type of crime, and more complete statistics are not yet available. Some critics have suggested Latinos are being targeted for arrest, a charge police deny.

Given the large number of Latinos affected by the riots, the impotence of Eastside leaders was particularly noticeable.

Some political observers attributed the inaction of Latino officials during the riots to ongoing factionalism. The established Latino political community has two dominant camps: supporters of Supervisor Molina and those who favor Alatorre.

A group of Latino leaders called a news conference last Friday at the Hollenbeck Youth Center in Boyle Heights, portraying it as a show of unity. But only Molina and her allies attended; Alatorre’s camp accused Molina of intentionally excluding them in the interest of political opportunism.

The friction within the Latino political community between dates back to when Molina--over the objections of Alatorre and others--ran for the state Assembly in the early 1980s.

She won the race but incurred the wrath of Alatorre and her former mentor, state Sen. Torres.

They have since found themselves on opposite sides in various races, including Molina’s successful campaigns for the Los Angeles City Council and the Board of Supervisors. In the latter race last year, she defeated Torres handily.

Times staff writers Frank Sotomayor, John L. Mitchell and Ronald J. Ostrow contributed to this story.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.