Confined to Gaza, performers find a way to break free — without crossing borders

The project, titled “At Home in Gaza and London,” is the brainchild of two London-based directors. Julian Maynard Smith founded the Station House Opera, an experimental theatrical company that has been using video feeds for over a decade to link per

Reporting from Gaza City — Walid Tafesh tried for more than a decade to escape the Gaza Strip.

The dancer applied seven times for permission to train and perform outside the Palestinian enclave. But Israel — which has enforced a blockade on the territory since the armed Islamist group Hamas took control in 2007 — denied him.

Then in late 2015 Tafesh spotted a somewhat cryptic post on Facebook inviting artists in Gaza to join a workshop in London — without crossing any borders.

“The aim is to create a performance piece that surpasses the intervening borders by creating a third shared space through an innovative use of the internet,” it said.

Intrigued, Tafesh fired off an application with links to his dance videos on YouTube.

It was the beginning of a collaboration that landed the 27-year-old on stages in London and Liverpool, England, this summer — thanks to video technology that melds performances in Gaza and Britain in real time for theater audiences in both places.

It was, Tafesh said, a “dream come true.”

More shows are planned in Manchester and other cities next year. The project, titled “At Home in Gaza and London,” is the brainchild of two London-based directors.

Julian Maynard Smith founded the Station House Opera, an experimental theatrical company that has been using live video feeds for over a decade to link performance spaces, making it appear as if artists in different cities are interacting in the same rooms and streets.

But it was Taghrid Choucair-Vizoso, who grew up in Lebanon, home to about 450,000 Palestinian refugees, who hit on the idea of using the technology to partner with artists in Gaza.

“He was working with places like Berlin and even Sao Paulo,” she said of her co-director. “But it dawned on me at one point that artists in those cities are able to readily travel for the most part. And then I thought how powerful this technology could be in bringing together people that can’t work in the same space.”

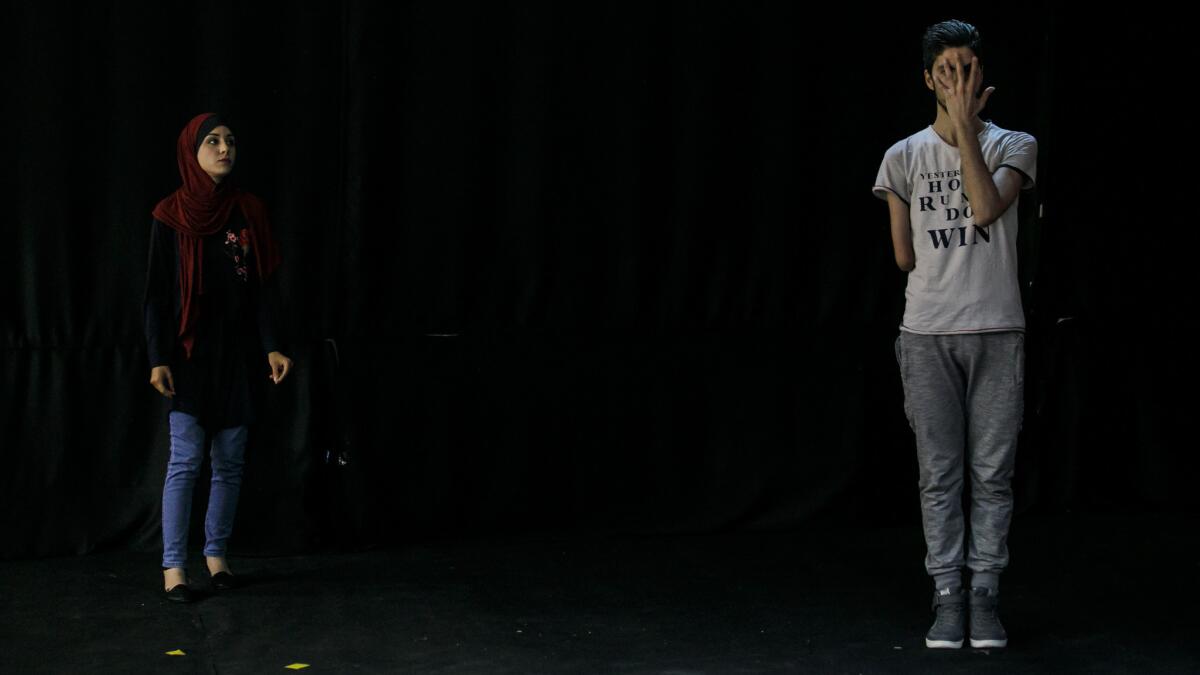

The resulting performances — in which five Gazans and four Londoners explore each other’s worlds through dance, song, food, play and conversation — are a poignant reminder of the Gazans’ isolation and a creative way for the performers to break free.

“Of course, it was about the most difficult place you could choose to do it,” Maynard Smith said.

Gaza gets only about four hours of electricity a day, requiring the use of an expensive generator to keep the lights and computers on. Internet connections are slow and unreliable. And even basic equipment, such as a backup power supply, was hard to find because Israel restricts the entry of components it deems could be used for military purposes.

Time and again during rehearsals at the Battersea Arts Center in London and the Wedad Society for Community Rehabilitation in Gaza City, the connection between the venues was lost because of power cuts in Gaza.

Rather than fight the inevitable glitches, the directors decided to incorporate them into the show.

When the audience in Gaza was plunged into darkness during a performance in late June, lights were switched off in London too, and prerecorded audio was played in which a Gazan cast member described how she copes with the frequent outages. When the connection was restored, the show picked up where it left off.

Maynard Smith tried to bring better computers and cameras with ultra-wide-angle lenses to the team in Gaza. But the Israeli authorities did not allow in the equipment.

Maynard Smith’s trip, which took place in March, lasted just two days. When deadly protests broke out along the security barriers between Gaza and Israel, he left because the aid group that had facilitated the visit was concerned about his safety.

It was the only time he got to meet the cast and crew in Gaza in person. Even so, close bonds were forged during hours of intense discussion and improvisation over the video links. At the end of each rehearsal, the performers would gather around monitors at both locations and blow kisses to each other.

“I do forget that we’re over 2,000 miles apart,” Choucair-Vizoso said. “I finish the day’s work, and I feel like I have been in Gaza, rather than in London.”

The participants tried to steer clear of politics, drawing instead on their own experiences and the questions they posed to each other about life in their respective cities as they developed the script together. There are scenes about dating, marriage, children and the lousy British weather.

But in Gaza, politics have a way of bleeding into everything else.

In one scene, Hamza Saftawi, a Palestinian journalist with no previous acting experience, discusses the imminent release of his father from an Israeli jail with one of the show’s directors. Saftawi was 9 when his father was arrested.

“It is like he is just raising up again from the ashes,” he confides to Maynard Smith. “I don’t have any idea how I’m going to deal with that.”

In another scene, the London-based actor Owl Young asks one of his Gaza counterparts about the “massacre,” a reference to the ongoing protests that have claimed the lives of more than 150 Palestinians by Israeli fire.

“What massacre?” the Gazan actor, Ali Hassany, replies sharply. “It’s not the first massacre, and it won’t be the last.”

There were heated discussions about how to address the bloodshed in the show. For Choucair-Vizoso, the protests seemed too momentous to ignore. But Hassany and others in Gaza wanted no part in that.

“I’m tired of being portrayed as the victim,” Hassany says in a scene lifted straight from those debates. “I just want to make a show about love, about life.”

There isn’t much of a theater culture in Gaza, a conservative and deeply impoverished place where most people are too busy trying to make ends meet to indulge in such pursuits — especially if they cost money.

Tafesh had never seen professional theater before he answered the Facebook post in 2015.

Born in Saudi Arabia, he was 10 when his Palestinian parents moved the family back to Gaza. He struggled to adjust and was often teased by other children about his missing right arm, a birth defect.

One summer, his parents sent him to a camp for children with disabilities. There he discovered a talent for dabke, a traditional Arab line dance.

It became a refuge from the isolation and other cruelties of life in Gaza. He joined a troupe that is frequently invited to perform at weddings and festivals. But he yearned to learn contemporary dance styles too. So he started teaching himself by watching dance videos on YouTube.

Now he has a partner abroad: Tara Fatehi Irani, an Iranian performance artist who joined the project in London.

Together, they choreographed a duet, which they perform to “London Can Take It,” a track by the band Public Service Broadcasting that begins with the sound of air raid sirens during Germany’s Blitz of London in World War II.

On the screens that tower over them in Gaza and London, their movements appear as intimate as if they shared the same stage. He reaches out to touch her hair. She gently strokes his face.

Tafesh doubts they could get away with such gestures if they were in the same theater. In Gaza, female dancers don’t typically perform with men or in front of mixed audiences.

As the music picks up, their images are superimposed over each other to create a ghostly new form with both long and short hair and seven frenetically moving limbs.

“She completes me,” he said later.

“He completes me too,” she added.

Times staff writer Zavis reported from Gaza City and London, and special correspondent Salah from Gaza City.

Twitter: @alexzavis

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.