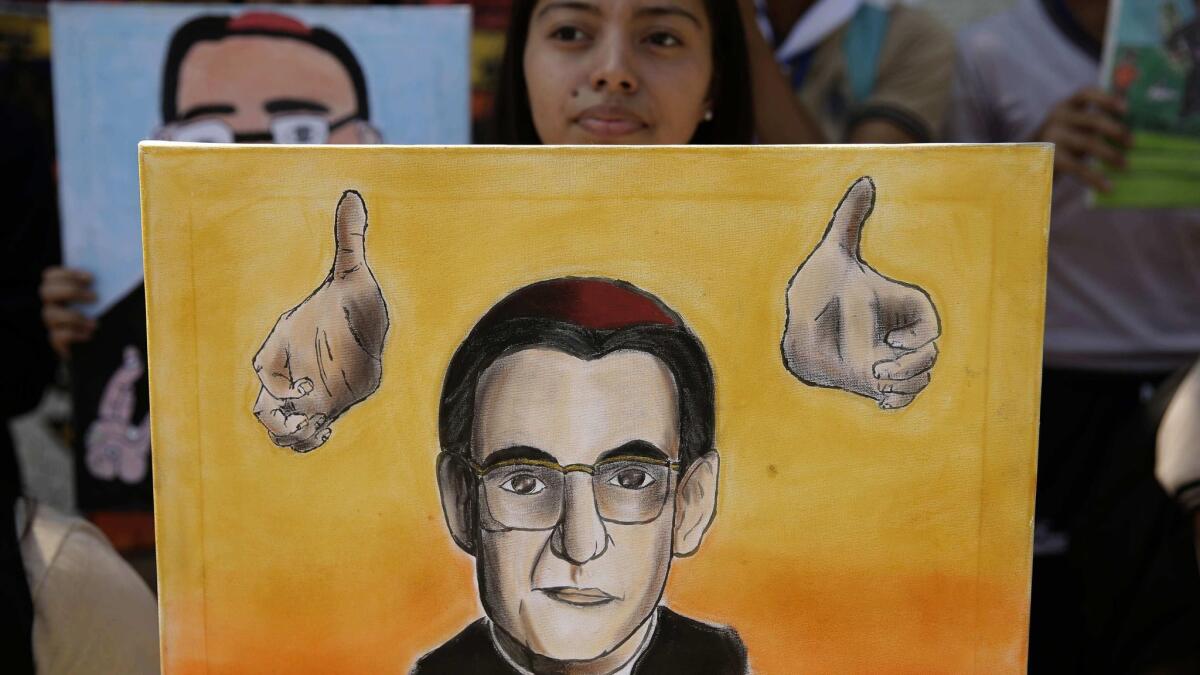

He championed the poor and was killed by a death squad in El Salvador. Decades later, Archbishop Oscar Romero will be made a saint

Reporting from ROME — Pope Francis has cleared the way to sainthood for Archbishop Oscar Romero, a beloved advocate for the poor and a fierce critic of El Salvador’s civil war who was slain in 1980 by a right-wing death squad.

The Vatican said Wednesday that Francis considers Romero a model for the Roman Catholic Church and had approved a miracle attributed to the archbishop — a requisite for canonization. It said Francis had also approved a miracle for Pope Paul VI, which means he, too, can be elevated to sainthood.

The news comes after years of efforts by church conservatives to block Romero’s canonization because of what they saw as his pro-left political views. It was celebrated by Salvadorans at home and in the United States, where Romero has long been seen as a source of strength and courage.

“We have gone through so much adversity,” said Oscar Dominguez, president of El Salvador Corridor, a stretch in the Pico-Union neighborhood of Los Angeles that honors the city’s large community of Salvadoran immigrants.

“But this gives us great motivation,” he said. “We have a hero. We have a saint.”

For some, the pending canonization brought hope during a trying time for Salvadorans.

President Trump’s January decision to rescind temporary protected status, known as TPS, has put about 262,000 Salvadorans at risk for deportation. Shortly after, it was widely reported that Trump referenced El Salvador when he used a profanity to complain to several members of Congress about some countries sending immigrants to the United States.

“This is coming at a time when the immigrant community, particularly the Salvadoran community, is being attacked by the federal administration,” said Assemblywoman Wendy Carrillo (D-Los Angeles), whose father died in El Salvador’s war.

“For me personally, Romero is a reminder that there are people who have paved the way, who have given their life to fight for equality and that what we’re living now has been lived before.”

In El Salvador, which has suffered high levels of violence, and where a wide gap remains between rich and poor, Cardinal Gregorio Rosa Chavez, a friend of Romero, called the news “a gift for the country and a promise that we can find a way out of so much violence, out of so much suffering.”

Many Salvadorans already consider Romero a saint. About 250,000 of them turned out for his beatification ceremonies in 2015, with some donning T-shirts declaring him “Saint Romero.”

Born in 1917, Romero began his career in the church as a relative conservative. But years of seeing how El Salvador’s poor were mistreated by a handful of rich oligarchs turned him against the elite. He was spurred to social action a few weeks after being appointed archbishop, when a fellow priest who had called for worker rights was slain.

It was the early days of the country’s civil war, which pitted rebels against a right-wing government backed by the United States.

In homilies and widely broadcast radio shows, Romero implored the government to do more for the poor and criticized the repressive tactics of the military. He gained international recognition when he wrote a letter to President Carter asking that the U.S. stop military aid to El Salvador.

The day before his death, Romero delivered a sermon begging army soldiers to not obey orders to kill civilians. “In the name of God … I beg you, I beseech you, I order you to stop the repression,” he said.

The next evening, while delivering a Mass at a chapel in a hospital, an unknown assassin approached the altar and shot him through the heart. Though no one was convicted for the crime, a United Nations truth commission after the end of the country’s civil war in 1992 concluded that army Maj. Roberto D’Aubuisson gave the order.

Chaos ensued at Romero’s funeral a few days later, and dozens of people were killed. The left and the right blamed each other for sparking the violence.

That incident and Romero’s death were seen as key events at the start of the 12-year civil war, in which 75,000 people were killed and thousands disappeared.

Conservatives within the church long blocked efforts to name Romero a saint, arguing he was slain for his politics, not his religion. The case for Romero’s canonization stalled at the Vatican under the papacy of John Paul II, part of a generation of clergy who disliked Romero’s associations with liberation theology, a movement that argued that while clergy members should care for the poor, they should also push for political changes to end poverty.

Francis, a Jesuit from Argentina who became pope in 2013, and whose core belief is helping the poor, has made Romero’s ascension a priority. He cleared the way for him to be beatified in 2015 and now for canonization, the last step to sainthood.

Father Thomas Reese, an analyst at the National Catholic Reporter, said Wednesday’s announcement “shows first and foremost that Pope Francis really liked and admired Oscar Romero.”

“To Francis, he was a bishop who cared for the poor and marginalized and was prepared to lay down his life for them,” Reese said. “That is the kind of bishop Francis wants, that is the model, and that is his message for bishops in Latin America.”

Normally, candidates for sainthood have to be attached to two miracles. In Romero’s case, however, he is declared a martyr— killed for his faith — which means only one miracle had to be attributed to him.

The miracle that cleared the way for Romero’s sainthood concerned the medically inexplicable cure of a pregnant, terminally ill Salvadoran woman who made a sudden recovery after her husband prayed to Romero, Vatican officials said.

James Martin, a Jesuit priest and author, said the Romero announcement signals a shift away from past conflicts for the church — and rights a historical wrong.

“The canonization of Oscar Romero is an immense step forward for the church, and a great wrong finally righted,” he tweeted. “Archbishop Romero, gunned down at the altar while saying Mass, after his prophetic defense of God’s poor in El Salvador, was clearly, and always, a martyr and a saint.”

In Los Angeles, where more than 350,000 Salvadorans live, the community celebrated the pope’s announcement. Many have waited decades for this moment.

Many Salvadoran refugees who fled the war saw themselves reflected in Romero, who used to visit pueblos and sit on the ground, alongside the road, eating sandwiches with villagers.

For years, community leaders in Los Angeles have found ways to pay tribute to his memory.

They named a clinic and a junior high after Romero. They also installed a statue of him at MacArthur Park and dedicated the intersection of Pico and Vermont as Monseñor Oscar Romero Square. Last year, a street was also named in his honor.

To read this article in Spanish click here

Times staff writers Linthicum, Bermudez and Wilkinson reported from Mexico City, Los Angeles and Washington, respectively, and special correspondent Kington from Rome.

UPDATES:

5:25 p.m.: This article was updated with more reaction and background.

3:35 p.m.: This article was updated throughout with Times reporting.

This article was originally published at 12:30 p.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.