Nicaragua scraps unpopular welfare plan, but unrest continues

Reporting from Managua, Nicaragua — A sense of smoldering discontent was evident in Nicaragua on Monday after President Daniel Ortega’s decision to cancel a welfare overhaul plan — a proposal that sparked days of deadly protests and looting in this Central American nation of 6 million.

On Monday afternoon, thousands of peaceful protesters — many waving Nicaraguan flags and some hoisting photos of people killed in the earlier protests — took to the streets of the capital, Managua. What began as protests against the welfare proposal morphed into demonstrations reflecting broader discontent with the Ortega government.

Human rights groups said more than two dozen people had been killed since street protests erupted last week after the government’s rollout of hikes in income and payroll taxes. The measures were meant to shore up the nation’s foundering social security system.

Police again clashed with student demonstrators on Sunday evening at one of the hubs of the protest movement, the Polytechnic University of Nicaragua in Managua. Many students had remained on university grounds despite what they called attacks from government security forces.

Speaking at the Vatican on Sunday, Pope Francis said that he was “very worried” about the deteriorating situation in Nicaragua and called for talks.

Finally, Ortega announced Sunday that the controversial social security overhaul had been scrapped. The move was a clear effort to quiet the growing strife, and it seemed to lead to an uneasy calm on the streets until the large-scale protests on Monday afternoon.

Marchers on Monday saluted the protesting youth of the Upoli, as the polytechnic university is known here.

Hundreds were injured in the days of turmoil across the country that followed the announcement of the social security decree. Reports indicated that more than 100 people had been arrested. Dozens of businesses were looted.

Although it was the social security changes that ignited the unrest, the street protests soon expanded to a wider condemnation of the Sandinista government and its leaders, Ortega and his wife, Vice President Rosario Murillo. Protesters voiced long-held grievances, including what they called the government’s throttling of dissent and of the opposition press.

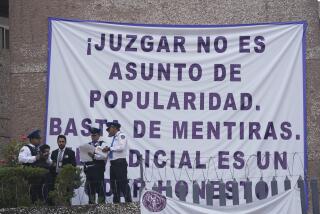

Some protesters in recent days hoisted banners demanding “Fuera Ortega” [Out With Ortega] and bearing other anti-government slogans aimed at Ortega, a former left-wing guerrilla leader who is serving his third consecutive term as president.

Critics accuse Ortega of seeking to establish a family dynasty with his wife.

“The people have risen against” Ortega, Alberto Antonio Fonseca, a student protester, said Monday in the city of Masaya, once a stronghold of the Sandinista rebel front that overthrew U.S.-backed dictator Anastasio Somoza in 1979. “We don’t want him as president any longer. There is too much repression.”

Protesters blamed police and government-allied security forces for the violence.

But Ortega charged on Saturday that “criminals” and gang members had infiltrated the protests as part of an unspecified “conspiracy” meant to destabilize the government.

His wife denounced the protesters as “minuscule groups” filled with “hate.”

The comments enraged the protesters and appeared to fan the flames of discontent.

“Mr. Ortega is wrong,” said Felipe Lanuza, a civil engineer who backed the street mobilizations. “The protests have been peaceful and the vandals and gangsters have been those on [Ortega’s] side.”

Added Tania Rivera, a protest supporter who runs a dental clinic in Managua: “We are professionals, grandparents, business owners — there are no gangsters. We are people who want a change in the country. That’s why we are on the streets.”

Business groups helped organize Monday’s anti-government demonstration, a sign that discontent with the Ortega administration extends beyond the student population.

Nicaragua’s business community has generally been allied with the Ortega government, but business leaders pointedly declined to condemn the protests, and some joined in. It was not clear whether that move signaled a more long-term fracture in Ortega’s relationship with the country’s business class.

On Monday, the U.S. State Department said it was reducing operations at its embassy in Managua and pulling out some of its employees and family members. An official advisory urged would-be visitors to reconsider travel to Nicaragua.

Nicaragua has generally been regarded as stable and relatively prosperous compared with some other Central American nations, notably crime-ridden El Salvador and Honduras. The country’s economy has grown steadily as the onetime Marxist Ortega has softened his denouncements of U.S. “imperialism” and embraced capitalism.

Ortega, 72, was a leader of the Sandinista front that overthrew the Somoza government in 1979 as the Cold War flared. He was elected president of Nicaragua in 1984 but lost a reelection bid in 1990, following years of the U.S.-backed Contra war against the Sandinista government.

Ortega returned to the presidency in 2006 and in 2016 was reelected in a landslide to a third consecutive term in balloting that the opposition denounced as rigged.

Ortega’s relationship with Washington has long been a contentious one. U.S. officials regularly criticize what they call an ongoing crackdown against the Nicaraguan opposition, while also assailing Managua’s foreign policy backing the governments of U.S. adversaries such as Cuba and Venezuela.

Special correspondent Miranda reported from Managua and Times staff writer McDonnell from Mexico City. Staff Writer Tracy Wilkinson in Washington and Cecilia Sanchez of The Times’ Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

Twitter: @PmcdonnellLAT

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.