Mexico City’s notoriously soft soil probably contributed to destruction from 7.1 earthquake

The extensive damage and structural collapse from Tuesday’s magnitude 7.1 earthquake in Mexico is still being tallied.

But in the coming days and weeks, one issue that seismologists will be addressing is the soft soil in the region — particularly in Mexico City — that may have heightened the destruction.

The soils under the city are part of an ancient lake bed that was filled thousands of years ago with wet clay deposits. Experts have likened the geology to a “bowl of Jello” that shakes violently in a major quake.

The soft soil was cited as a major factor in the massive damage and loss of life from the 1985 Mexico City quake.

That magnitude 8.1 quake shook Mexico City at 7:19 a.m. on Sept. 19, 1985. It toppled hundreds of buildings and killed an estimated 10,000 people.

1985 HORROR STORY

Violent waves batter Mexico City

In 1986, The Times published an extensive reconstruction by writer Robert A. Jones of why the quake a year earlier caused so much destruction. Here is an excerpt:

Shock waves from the earthquake began shooting across western Mexico toward the capital. The waves were grouped into two pulses produced by twin ruptures in the Orozco fracture zone off the Mexican coast.

Initially the waves were complex, containing many different frequencies. But over long distances the shorter frequencies were filtered out, leaving only long, smooth waves to strike the lake bed at Mexico City. Waves are measured by their "period," or the length of time that it takes to complete a cycle. These waves had cycles of 1.5 to 2 seconds, very long by earthquake standards.

In the city, some buildings began to sway in time with the waves. A few pounded against each other, acting like battering rams. Each sway became worse until the buildings tore themselves apart, the floors falling onto one another in a phenomenon known as "pancaking." At last count, 954 buildings collapsed inside the city, 1,100 others eventually will be demolished, and thousands of others suffered damage.

Within the lake bed, a transformation began. The elastic soil, saturated with water, amplified the motion four to five times its previous level. The waves struck the surface with undulating regularity that continued for the unusually long time of a minute.

In Mexico City … many 19th century, unreinforced buildings were left standing while more modern buildings of reinforced concrete collapsed. Engineers soon discovered a similarity in the buildings that failed: Almost all were mid-rise constructions ranging from six to 16 stories.

These buildings had a natural tendency to vibrate at the same rate as the shock waves: one cycle every 1.5 to 2 seconds. Like a child on a swing, the buildings swayed more and more each time a new shock wave pushed them until they collapsed.

The older buildings, though inherently weaker, were also stiffer because of the masonry construction, and their natural vibration patterns did not match the shock waves. They survived.

2017 QUAKE

Assessing the damage this time

The extent of the damage in Mexico City and elsewhere was still being tallied. But videos and images show numerous buildings damaged, with some appearing to collapse.

“It’s very horrendous,” said Guillermo Lozano, humanitarian and emergency affairs director for World Vision Mexico, a Christian humanitarian organization. “Most of the people were at work and children were at school.”

The earthquake struck just hours after a citywide drill commemorating the devastating 1985 earthquake. Across the city, people poured into the streets to walk home, searching for information on their relatives.

Lozano said some of the worst-hit buildings were short — just two or three floors high. “Mostly, they are very old buildings,” Lozano said. “Most of them are in the downtown of the city, and some, in the south of the city.”

The 1985 quake helped raise awareness of the danger soft soil poses when earthquakes strike. Extensive damage in San Francisco’s Marina District during the 1989 Loma Prieta quake further heightened concerns because that neighborhood had been built on fill. (Some of the debris below the district was from the great 1906 quake.)

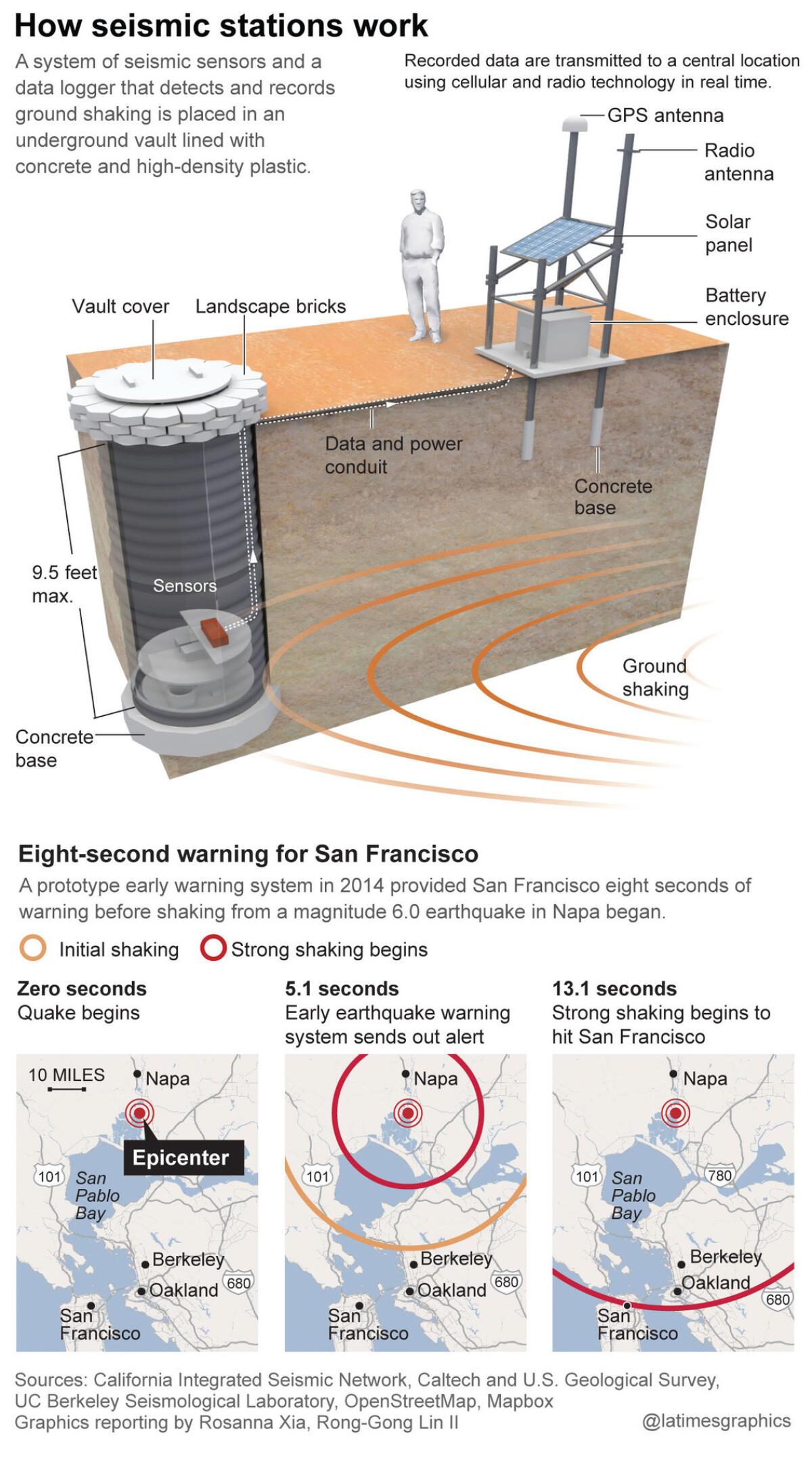

Since 1985, Mexico has improved its quake safety efforts. The country has an earthquake warning system that has given seconds of advance notice before several major quakes occurred.

The system worked during an 8.1 quake earlier this month and during Tuesday’s quake. California does not have a similar warning system.

A seismic warning system for the West Coast has been under development for years by the U.S. Geological Survey, the nation’s lead earthquake monitoring agency. President Trump’s budget would have ended the system before it launched. Officials were looking for “sensible and rational reductions and making hard choices to reach a balanced budget by 2027,” according to the administration’s proposal.

But the proposal to end the funding raised bipartisan complaints up and down the coast. Twenty-eight lawmakers in the California Legislature, including leaders from both parties, urged officials to protect the earthquake early warning system. Members of Congress from Southern California to the Canadian border say the system is crucial to public safety.

In July, a congressional committee voted to keep funding.

Already, early warning technology is being rolled out that will cause elevators to stop and open at the next floor, sparing occupants from becoming trapped; alert surgeons in hospitals to stop operations; and halt the flow of natural gas through major pipelines, reducing the risk of catastrophic fires.

The system is expected to begin limited operation by next year if stable funding continues.

Even before its completion, the network is beginning to slowly gain traction in both small and big ways.

A scattering of buildings are now equipped with audible alarms that will give occupants an advance warning ranging from seconds to more than a minute before the shaking from a major earthquake begins. And some already have automatic elevator shutdown systems installed.

UPDATES:

4:35 p.m.: Updated with information from Guillermo Lozano

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.