It was a Mexico City office building. Now, after the earthquake, it’s a tomb

Crews work on top of a collapsed building’s roof in Mexico City, drilling to get to bodies still inside

What was once a concrete office building has become a tomb.

The upper stories at the building at Avenida Alvaro Obregon 286, in the Condesa neighborhood of Mexico City, have collapsed, leaving entire floors stacked like pancakes.

Signs of a once-bustling office peek out. Potted plants. The remnants of vertical blinds. A navy blue bench cushion. Binders. A black filing cabinet smashed open. A “Star Wars” toy model. An electrical outlet ripped from the wall.

All of it now squeezed in a vise of heavy concrete floors failed by their pillars.

The stench of death pervades the scene. It has been days since the last person was extracted from the building alive.

Twenty bodies have been found. Crews think 10 to 20 remain.

The building looks as if a giant had come and pounded a fist into the roof.

The destruction is so complete that it is unclear how many stories there were. Five seems like the best guess. In fact, there were seven.

Some workers now access the roof from the top of a neighboring three-story building.

In the middle is a failed concrete pillar, which once formed part of the skeleton of the building. It is now a broken spine, with steel reinforcement bars once encased in concrete dangling like severed nerves.

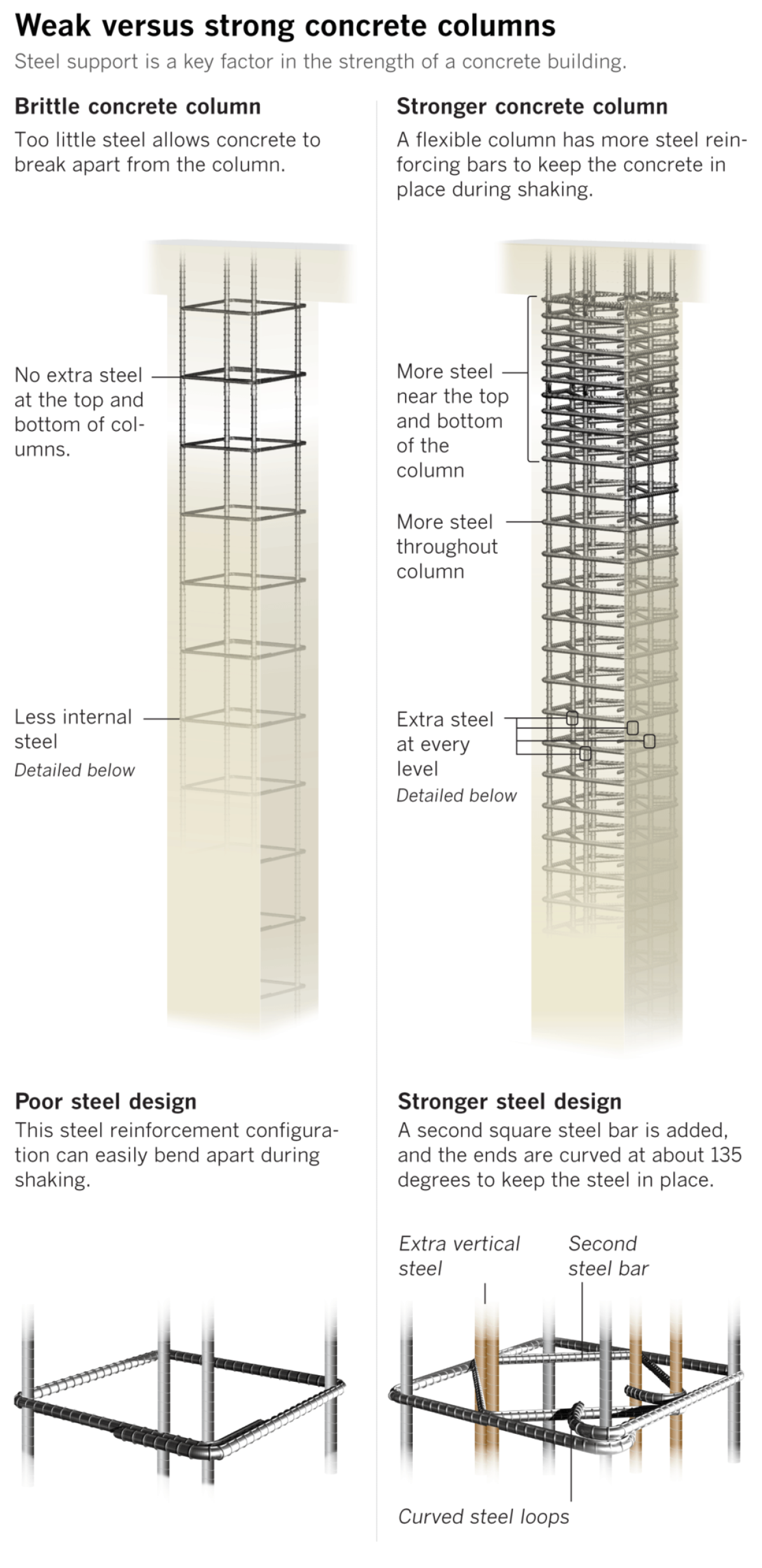

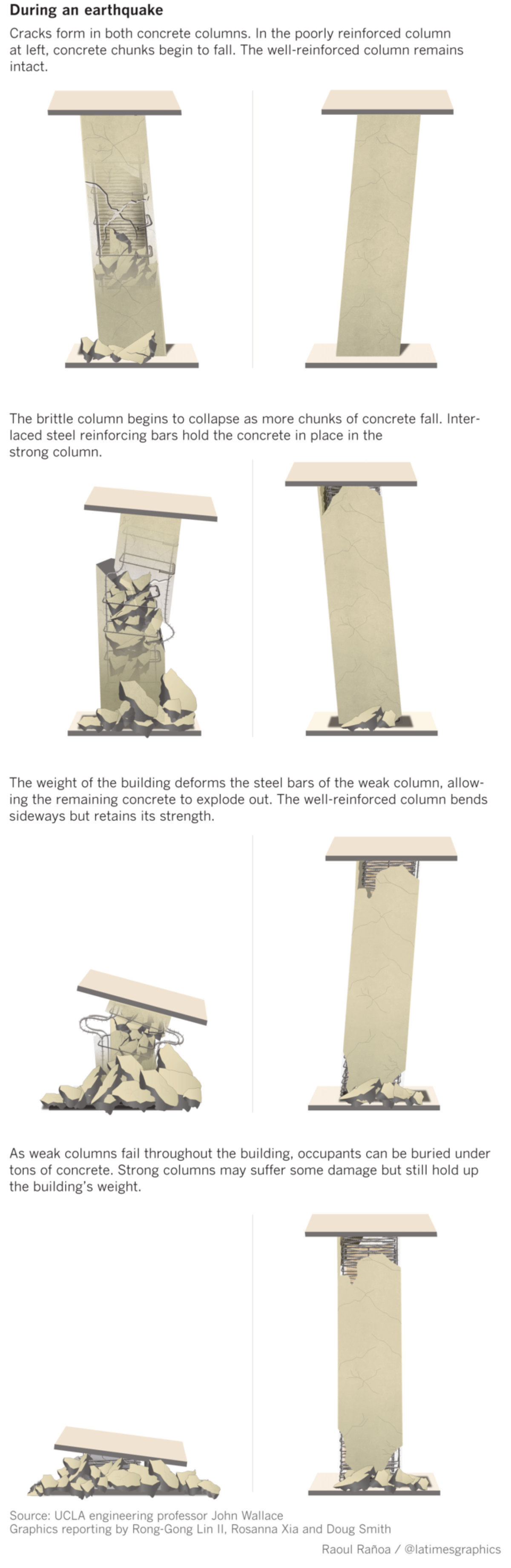

The wreckage shows a common defect in concrete buildings of this era: not enough steel rebar embedded in the concrete to contain it as it crumbles and keep the pillars intact, suggests Kit Miyamoto, a Los Angeles-based structural engineer visiting Mexico City to learn from the quake.

Most likely, concrete started to burst from where vertical columns intersected with the horizontal beams. The debris shows a lack of enough steel reinforcing bars at these crucial joints of the building.

Once the columns started to break apart, there was nothing left to hold up the building.

Anna Lang, a California-based earthquake engineer with Miyamoto’s firm, said the building probably suffered severe side-to-side shaking.

The building was erected before — and survived — the 1985 magnitude 8 earthquake that was centered 250 miles from the capital and killed at least 4,200 people. But it did not withstand this one, a magnitude 7.1 temblor that came from 80 miles away.

California has many of the same style buildings, constructed in the postwar era and only widely understood to be a hazard in 1971 after new concrete hospital buildings came crashing down in Los Angeles during the Sylmar earthquake.

New concrete buildings in both California and Mexico City are now required to have more extensive rebar, such as more hoops along the columns and beams. But most places haven’t required old buildings to be fixed.

Los Angeles recently passed a law requiring such retrofits. But it allows owners 25 years to do it once a seismic evaluation is ordered by the city, which is still compiling its list of buildings.

“There is the urban myth in L.A.: My building went through Northridge, so we are safe,” Miyamoto said. “Look at this building. A smaller earthquake” brought it down.

“Different earthquakes affect different buildings,” Miyamoto said.

The earthquake came at a particularly bad time — just after 1 p.m., ahead of the usual lunchtime in Mexico. So it was full of workers, said Corey Michaud, a disaster response expert with Miyamoto.

Unlike in California, where people are taught to drop, cover and hold on in an earthquake — which protects people from being crushed by falling building facades if they try to escape — Mexico City residents are taught to flee buildings.

The city had conducted a drill that morning because it happened to be the 32nd anniversary of the 1985 quake, and workers at the building had practiced running down an exterior steel stairwell. That training may have saved lives. Miyamoto was told that a number of people escaped the building before it collapsed.

Videos of other large, brittle concrete structures falling in this earthquake suggest that some collapses happened shortly after — and not during — the time at which the shaking was most violent. That may have given people time to get out.

Miyamoto said he went into the building to help consult on the structural stability of the ruins. He said he saw bodies clustered around the stairwell exits. A few more seconds, and more people might have been able to make it, he said.

Dozens of people stood atop the roof, drilling to recover bodies underneath a layer of thick concrete. As rubble was plucked away, it was passed in buckets down a chain of people that extended to the next building and poured into a chute down below to a dump truck.

Other workers, fueled by cans of Red Bull and Coca-Cola, painstakingly cut trenches and holes in the roof in an attempt to reach the dead.

“It’s just incredible,” Miyamoto said of the effort.

This earthquake was actually not the Big One for Mexico City, but a moderate one, he said. It was a warning for the capital — and any other earthquake-prone areas, including Los Angeles.

“If it’s a close earthquake, my God, it’s going to be 100 times worse,” Miyamoto said.

And a Big One in Southern California could be worse than what Mexico City has experienced in the last week.

“We are going to experience the exact same thing in L.A., the exact sights and smell,” he said.

Twitter: @ronlin

ALSO

Fixing L.A. buildings vulnerable to collapse is vital before next big earthquake, Garcetti says

Here’s what earthquake magnitudes mean—and why an 8 can be so much scarier than a 6

Could your building collapse in a major earthquake? Look up your address on these databases

UPDATES:

Sept. 28, 1:23 p.m.: This article was updated to include the size of the building: seven stories.

This article was originally published on Sept. 27 at 3 a.m.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.